Broadcasting

Broadcasting is the distribution of audio or video content to a dispersed audience via any electronic mass communications medium, but typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum (radio waves), in a one-to-many model.[1][2] Broadcasting began with AM radio, which came into popular use around 1920 with the spread of vacuum tube radio transmitters and receivers. Before this, all forms of electronic communication (early radio, telephone, and telegraph) were one-to-one, with the message intended for a single recipient. The term broadcasting evolved from its use as the agricultural method of sowing seeds in a field by casting them broadly about.[3] It was later adopted for describing the widespread distribution of information by printed materials[4] or by telegraph.[5] Examples applying it to "one-to-many" radio transmissions of an individual station to multiple listeners appeared as early as 1898.[6]

Over the air broadcasting is usually associated with radio and television, though more recently, both radio and television transmissions have begun to be distributed by cable (cable television). The receiving parties may include the general public or a relatively small subset; the point is that anyone with the appropriate receiving technology and equipment (e.g., a radio or television set) can receive the signal. The field of broadcasting includes both government-managed services such as public radio, community radio and public television, and private commercial radio and commercial television. The U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, title 47, part 97 defines "broadcasting" as "transmissions intended for reception by the general public, either direct or relayed".[7] Private or two-way telecommunications transmissions do not qualify under this definition. For example, amateur ("ham") and citizens band (CB) radio operators are not allowed to broadcast. As defined, "transmitting" and "broadcasting" are not the same.

Transmission of radio and television programs from a radio or television station to home receivers by radio waves is referred to as "over the air" (OTA) or terrestrial broadcasting and in most countries requires a broadcasting license. Transmissions using a wire or cable, like cable television (which also retransmits OTA stations with their consent), are also considered broadcasts but do not necessarily require a license (though in some countries, a license is required). In the 2000s, transmissions of television and radio programs via streaming digital technology have increasingly been referred to as broadcasting as well.

History

The earliest broadcasting consisted of sending telegraph signals over the airwaves, using Morse code, a system developed in the 1830s by Samuel F.B. Morse, physicist Joseph Henry and Alfred Vail. They developed an electrical telegraph system which sent pulses of electric current along wires which controlled an electromagnet that was located at the receiving end of the telegraph system. A code was needed to transmit natural language using only these pulses, and the silence between them. Morse therefore developed the forerunner to modern International Morse code. This was particularly important for ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore communication, but it became increasingly important for business and general news reporting, and as an arena for personal communication by radio amateurs (Douglas, op. cit.). Audio radio broadcasting began experimentally in the first decade of the 20th century. By the early 1920s audio radio broadcasting became a household medium, at first on the AM band and later on FM. Television broadcasting started experimentally in the 1920s and became widespread after World War II, using VHF and UHF spectrum. Satellite broadcasting was initiated in the 1960s and moved into general industry usage in the 1970s, with DBS (Direct Broadcast Satellites) emerging in the 1980s.

Originally all broadcasting was composed of analog signals using analog transmission techniques but in the 2000s, broadcasters have switched to digital signals using digital transmission. In general usage, broadcasting most frequently refers to the transmission of information and entertainment programming from various sources to the general public.

- Analog audio radio vs. Digital audio radio (HD Radio, Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB), Satellite radio and Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM)

- Analog television vs. Digital television

- Wireless

The world's technological capacity to receive information through one-way broadcast networks more than quadrupled during the two decades from 1986 to 2007, from 432 exabytes of (optimally compressed) information, to 1.9 zettabytes.[8] This is the information equivalent of 55 newspapers per person per day in 1986, and 175 newspapers per person per day by 2007.[9]

Methods

Historically, there have been several methods used for broadcasting electronic media audio and video to the general public:

- Telephone broadcasting (1881–1932): the earliest form of electronic broadcasting (not counting data services offered by stock telegraph companies from 1867, if ticker-tapes are excluded from the definition). Telephone broadcasting began with the advent of Théâtrophone ("Theatre Phone") systems, which were telephone-based distribution systems allowing subscribers to listen to live opera and theatre performances over telephone lines, created by French inventor Clément Ader in 1881. Telephone broadcasting also grew to include telephone newspaper services for news and entertainment programming which were introduced in the 1890s, primarily located in large European cities. These telephone-based subscription services were the first examples of electrical/electronic broadcasting and offered a wide variety of programming.

- Radio broadcasting (experimentally from 1906, commercially from 1920); audio signals sent through the air as radio waves from a transmitter, picked up by an antenna and sent to a receiver. Radio stations can be linked in radio networks to broadcast common radio programs, either in broadcast syndication, simulcast or subchannels.

- Television broadcasting (telecast), experimentally from 1925, commercially from the 1930s: an extension of radio to include video signals.

- Cable radio (also called "cable FM", from 1928) and cable television (from 1932): both via coaxial cable, originally serving principally as transmission media for programming produced at either radio or television stations, but later expanding into a broad universe of cable-originated channels.

- Direct-broadcast satellite (DBS) (from c. 1974) and satellite radio (from c. 1990): meant for direct-to-home broadcast programming (as opposed to studio network uplinks and downlinks), provides a mix of traditional radio or television broadcast programming, or both, with dedicated satellite radio programming. (See also: Satellite television)

- Webcasting of video/television (from c. 1993) and audio/radio (from c. 1994) streams: offers a mix of traditional radio and television station broadcast programming with dedicated Internet radio and Internet television.

Economic models

There are several means of providing financial support for continuous broadcasting:

- Commercial broadcasting: for-profit, usually privately owned stations, channels, networks, or services providing programming to the public, supported by the sale of air time to advertisers for radio or television advertisements during or in breaks between programs, often in combination with cable or pay cable subscription fees.

- Public broadcasting: usually non-profit, publicly owned stations or networks supported by license fees, government funds, grants from foundations, corporate underwriting, audience memberships, contributions or a combination of these.

- Community broadcasting: a form of mass media in which a television station, or a radio station, is owned, operated or programmed, by a community group to provide programs of local interest known as local programming. Community stations are most commonly operated by non-profit groups or cooperatives; however, in some cases they may be operated by a local college or university, a cable company or a municipal government.

Broadcasters may rely on a combination of these business models. For example, in the United States, National Public Radio (NPR) and the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS, television) supplement public membership subscriptions and grants with funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which is allocated bi-annually by Congress. US public broadcasting corporate and charitable grants are generally given in consideration of underwriting spots which differ from commercial advertisements in that they are governed by specific FCC restrictions, which prohibit the advocacy of a product or a "call to action".

Recorded and live forms

The first regular television broadcasts started in 1937. Broadcasts can be classified as "recorded" or "live". The former allows correcting errors, and removing superfluous or undesired material, rearranging it, applying slow-motion and repetitions, and other techniques to enhance the program. However, some live events like sports television can include some of the aspects including slow-motion clips of important goals/hits, etc., in between the live television telecast. American radio-network broadcasters habitually forbade prerecorded broadcasts in the 1930s and 1940s requiring radio programs played for the Eastern and Central time zones to be repeated three hours later for the Pacific time zone (See: Effects of time on North American broadcasting). This restriction was dropped for special occasions, as in the case of the German dirigible airship Hindenburg disaster at Lakehurst, New Jersey, in 1937. During World War II, prerecorded broadcasts from war correspondents were allowed on U.S. radio. In addition, American radio programs were recorded for playback by Armed Forces Radio radio stations around the world.

A disadvantage of recording first is that the public may know the outcome of an event from another source, which may be a "spoiler". In addition, prerecording prevents live radio announcers from deviating from an officially approved script, as occurred with propaganda broadcasts from Germany in the 1940s and with Radio Moscow in the 1980s. Many events are advertised as being live, although they are often "recorded live" (sometimes called "live-to-tape"). This is particularly true of performances of musical artists on radio when they visit for an in-studio concert performance. Similar situations have occurred in television production ("The Cosby Show is recorded in front of a live television studio audience") and news broadcasting.

A broadcast may be distributed through several physical means. If coming directly from the radio studio at a single station or television station, it is simply sent through the studio/transmitter link to the transmitter and hence from the television antenna located on the radio masts and towers out to the world. Programming may also come through a communications satellite, played either live or recorded for later transmission. Networks of stations may simulcast the same programming at the same time, originally via microwave link, now usually by satellite. Distribution to stations or networks may also be through physical media, such as magnetic tape, compact disc (CD), DVD, and sometimes other formats. Usually these are included in another broadcast, such as when electronic news gathering (ENG) returns a story to the station for inclusion on a news programme.

The final leg of broadcast distribution is how the signal gets to the listener or viewer. It may come over the air as with a radio station or television station to an antenna and radio receiver, or may come through cable television[10] or cable radio (or "wireless cable") via the station or directly from a network. The Internet may also bring either internet radio or streaming media television to the recipient, especially with multicasting allowing the signal and bandwidth to be shared. The term "broadcast network" is often used to distinguish networks that broadcast an over-the-air television signals that can be received using a tuner (television) inside a television set with a television antenna from so-called networks that are broadcast only via cable television (cablecast) or satellite television that uses a dish antenna. The term "broadcast television" can refer to the television programs of such networks.

Social impact

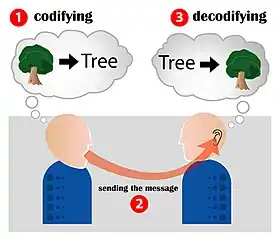

The sequencing of content in a broadcast is called a schedule. As with all technological endeavors, a number of technical terms and slang have developed. A list of these terms can be found at List of broadcasting terms.[11] Television and radio programs are distributed through radio broadcasting or cable, often both simultaneously. By coding signals and having a cable converter box with decoding equipment in homes, the latter also enables subscription-based channels, pay-tv and pay-per-view services. In his essay, John Durham Peters wrote that communication is a tool used for dissemination. Durham stated, "Dissemination is a lens—sometimes a usefully distorting one—that helps us tackle basic issues such as interaction, presence, and space and time...on the agenda of any future communication theory in general" (Durham, 211).[2] Dissemination focuses on the message being relayed from one main source to one large audience without the exchange of dialogue in between. It is possible for the message to be changed or corrupted by government officials once the main source releases it. There is no way to predetermine how the larger population or audience will absorb the message. They can choose to listen, analyze, or simply ignore it. Dissemination in communication is widely used in the world of broadcasting.

Broadcasting focuses on getting a message out and it is up to the general public to do what they wish with it. Durham also states that broadcasting is used to address an open-ended destination (Durham, 212). There are many forms of broadcasting, but they all aim to distribute a signal that will reach the target audience. Broadcasters typically arrange audiences into entire assemblies (Durham, 213). In terms of media broadcasting, a radio show can gather a large number of followers who tune in every day to specifically listen to that specific disc jockey. The disc jockey follows the script for his or her radio show and just talks into the microphone.[2] He or she does not expect immediate feedback from any listeners. The message is broadcast across airwaves throughout the community, but there the listeners cannot always respond immediately, especially since many radio shows are recorded prior to the actual air time.

See also

- Analog television

- Bandplan

- Broadcast engineering

- Broadcast quality

- Broadcast television systems – contains the standards of the topic

- Broadcasting in the United States

- Cablecast

- Frank Conrad

- Dead air

- Digital television

- Electronic media

- European Broadcasting Union (EBU)

- List of broadcast satellites

- List of broadcasting terms

- List of radio awards

- List of television awards

- Narrowcasting

- NaSTA

- Nonbroadcast Multiple Access Network (NBMA)

- North American broadcast television frequencies

- Outside broadcast

- Radio Act of 1927, United States

- Reality television

- Society of Broadcast Engineers (SBE)

- Television broadcasting in Australia

- Television transmitter

- Transposer

- Wilkinsburg

Notes and references

- Peters, John Durham (1999). Speaking into the Air. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66276-3.

- Speaking into the Air. Press.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Douglas, Susan J. (1987). Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899–1922. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3832-3.

- The Hand-book of Wyoming and Guide to the Black Hills and Big Horn Regions, 1877, p. 74: "in the case of the estimates sent broadcast by the Department of Agriculture, in its latest annual report, the extent has been sadly underestimated".

- "Medical Advertising", Saint Louis Medical and Surgical Journal, December 1886, p. 334: "operations formerly described in the city press alone, are now sent broadcast through the country by multiple telegraph".

- "Wireless Telegraphy", The Electrician (London), October 14, 1898, p. 815: "there are rare cases where, as Dr. Lodge once expressed it, it might be advantageous to 'shout' the message, spreading it broadcast to receivers in all directions".

- Electronic Code of Federal Regulation. (2017, September 28`). Retrieved October 02, 2017

- "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information", Martin Hilbert and Priscila López (2011), Science, 332(6025), 60–65; free access to the article through here: martinhilbert.net/WorldInfoCapacity.html

- "video animation on The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information from 1986 to 2010". Ideas.economist.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- "Информационно – развлекательный портал – DIWAXX.RU – мобильная связь, безопасность ПК и сетей, компьютеры и программы, общение, железо, секреты Windows, web-дизайн, раскрутка и оптимизация сайта, партнерские программы". Diwaxx.ru. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- Qsl.net https://web.archive.org/web/20171116173416/http://www.qsl.net/n2jac/jota2k/BROADCAST%20GLOSSARY.htm. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Bibliography

- Carey, James (1989) Communication as Culture, Routledge, New York and London, pp. 201–30

- Kahn, Frank J., ed. Documents of American Broadcasting, fourth edition (Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1984).

- Lichty Lawrence W., and Topping Malachi C., eds. American Broadcasting: A Source Book on the History of Radio and Television (Hastings House, 1975).

- Meyrowitz, Joshua., Mediating Communication: What Happens? in Downing, J., Mohammadi, A., and Sreberny-Mohammadi, A., (eds) Questioning The Media (Sage, Thousand Oaks, 1995) pp. 39–53

- Peters, John Durham. "Communication as Dissemination." Communication as...Perspectives on Theory. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage, 2006. 211–22.

- Thompson, J., The Media and Modernity, in Mackay, H and O'Sullivan, T (eds) The Media Reader: Continuity and Transformation., (Sage, London, 1999) pp. 12–27

Further reading

- Gilbert, Sean; Nelson, John; Jacobs, George, World Radio TV Handbook 2007, Watson-Guptill, 2006. ISBN 0-9535864-9-9. The 2007 edition of the World Radio TV Handbook.

- Wells, Alan, World Broadcasting: A Comparative View, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996. ISBN 1-56750-245-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Broadcasting. |

| Look up broadcasting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Radio Locator, for American radio station with format, power, and coverage information.

- Jim Hawkins' Radio and Broadcast Technology Page – History of broadcast transmitter

- Indie Digital Cinema Services – Broadcast Industry Glossary