Burger's Daughter

Burger's Daughter is a political and historical novel by the South African Nobel Prize in Literature-winner Nadine Gordimer, first published in the United Kingdom in June 1979 by Jonathan Cape. The book was expected to be banned in South Africa, and a month after publication in London the import and sale of the book in South Africa was prohibited by the Publications Control Board. Three months later, the Publications Appeal Board overturned the banning and the restrictions were lifted.

First edition dust jacket (Jonathan Cape, 1979) | |

| Author | Nadine Gordimer |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Craig Dodd |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical novel, political novel |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape (UK) Viking (US) |

Publication date | June 1979 (UK) October 1979 (US) |

| Media type | Print, ebook and audio[1] |

| Pages | 364 (hardcover) |

| Award | Central News Agency Literary Award |

| ISBN | 978-0-224-01690-2 |

| OCLC | 5834280 |

Burger's Daughter details a group of white anti-apartheid activists in South Africa seeking to overthrow the South African government. It is set in the mid-1970s, and follows the life of Rosa Burger, the title character, as she comes to terms with her father Lionel Burger's legacy as an activist in the South African Communist Party (SACP). The perspective shifts between Rosa's internal monologue (often directed towards her father or her lover Conrad), and the omniscient narrator. The novel is rooted in the history of the anti-apartheid struggle and references to actual events and people from that period, including Nelson Mandela and the 1976 Soweto uprising.

Gordimer herself was involved in South African struggle politics, and she knew many of the activists, including Bram Fischer, Mandela's treason trial defence lawyer. She modelled the Burger family in the novel loosely on Fischer's family, and described Burger's Daughter as "a coded homage" to Fischer.[2] While banned in South Africa, a copy of the book was smuggled into Mandela's prison cell on Robben Island, and he reported that he "thought well of it".[3]

The novel was generally well-received by critics. A reviewer for The New York Times said that Burger's Daughter is Gordimer's "most political and most moving novel",[4] and a review in The New York Review of Books described the style of writing as "elegant", "fastidious" and belonging to a "cultivated upper class".[5] A critic in The Hudson Review had mixed feelings about the book, saying that it "gives scarcely any pleasure in the reading but which one is pleased to have read nonetheless".[6] Burger's Daughter won the Central News Agency Literary Award in 1980.

Plot summary

The novel begins in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1974 during apartheid. Rosa Burger[lower-alpha 1] is 26, and her father, Lionel Burger, a white Afrikaner anti-apartheid activist, has died in prison after serving three years of a life sentence for treason. When she was 14, her mother, Cathy Burger, also died in prison. Rosa had grown up in a family that actively supported the overthrow of the apartheid government, and the house they lived in opened its doors to anyone supporting the struggle, regardless of colour. Living with them was "Baasie" (little boss),[8] a black boy Rosa's age the Burgers had "adopted" when his father had died in prison. Baasie and Rosa grew up as brother and sister. Rosa's parents were members of the outlawed South African Communist Party (SACP), and had been arrested several times when she was a child. When Rosa was nine, she was sent to stay with her father's family; Baasie was sent elsewhere, and she lost contact with him.

With the Burger's house now empty, Rosa sells it and moves in with Conrad, a student who had befriended her during her father's trial. Conrad questions her about her role in the Burger family and asks why she always did what she was told. Later Rosa leaves Conrad and moves into a flat on her own and works as a physiotherapist. In 1975 Rosa attends a party of a friend in Soweto, and it is there that she hears a black university student dismissing all whites' help as irrelevant, saying that whites cannot know what blacks want, and that blacks will liberate themselves. Despite being labelled a Communist and under surveillance by the authorities, Rosa manages to get a passport, and flies to Nice in France to spend several months with Katya, her father's first wife. There she meets Bernard Chabalier, a visiting academic from Paris. They become lovers and he persuades her to return with him to Paris.

Before joining Bernard in Paris, Rosa stays in a flat in London for several weeks. Now that she has no intention of honouring the agreement of her passport, which was to return to South Africa within a year, she openly introduces herself as Burger's daughter. This attracts the attention of the media and she attends several political events. At one such event, Rosa sees Baasie, but when she tries to talk to him, he starts criticising her for not knowing his real name (Zwelinzima Vulindlela). He says that there is nothing special about her father having died in prison as many black fathers have also died there, and adds that he does not need her help. Rosa is devastated by her childhood friend's hurtful remarks, and overcome with guilt, she abandons her plans of going into exile in France and returns to South Africa.

Back home she resumes her job as a physiotherapist in Soweto. Then in June 1976 Soweto school children start protesting about their inferior education and being taught in Afrikaans. They go on a rampage, which includes killing white welfare workers. The police brutally put down the uprising, resulting in hundreds of deaths. In October 1977, many organisations and people critical of the white government are banned, and in November 1977 Rosa is detained. Her lawyer, who also represented her father, expects charges to be brought against her of furthering the aims of the banned SACP and African National Congress (ANC), and of aiding and abetting the students' revolt.

Background

In a 1980 interview, Gordimer stated that she was fascinated by the role of "white hard-core Leftists" in South Africa, and that she had long envisaged the idea for Burger's Daughter.[9] Inspired by the work of Bram Fischer, she published an essay about him in 1961 entitled "Why Did Bram Fischer Choose to Go to Jail?"[10] Fischer was the Afrikaner advocate and Communist who was Nelson Mandela's defence lawyer during his 1956 Treason Trial and his 1965 Rivonia Trial.[11] As a friend of many of the activist families, including Fischer's, Gordimer knew these families' children were "politically groomed" for the struggle, and were taught that "the struggle came first" and they came second.[12] She modelled the Burger family in the novel loosely on Fischer's family,[13] and Lionel Burger on Fischer himself.[14][15] While Gordimer never said the book was about Fischer, she did describe it as "a coded homage" to him.[2] Before submitting the manuscript to her publisher, Gordimer gave it to Fischer's daughter, Ilse Wilson (née Fischer) to read, saying that, because of connections people might make to her family, she wanted her to see it first. When Wilson returned the manuscript to Gordimer, she told the writer, "You have captured the life that was ours."[16] After Gordimer's death in July 2014, Wilson wrote that Gordimer "had the extraordinary ability to describe a situation and capture the lives of people she was not necessarily a part of."[16]

Gordimer's homage to Fischer extends to using excerpts from his writings and public statements in the book.[17] Lionel Burger's treason trial speech from the dock[18] is taken from the speech Fischer gave at his own trial in 1966.[15][17] Fischer was the leader of the banned SACP who was given a life sentence for furthering the aims of communism and conspiracy to overthrow the government. Quoting people like Fischer was not permitted in South Africa.[17] All Gordimer's quotes from banned sources in Burger's Daughter are unattributed, and also include writings of Joe Slovo, a member of the SACP and the outlawed ANC, and a pamphlet[19] written and distributed by the Soweto Students Representative Council during the Soweto uprising.[15]

Gordimer herself became involved in South African struggle politics after the arrest of a friend, Bettie du Toit, in 1960 for trade unionist activities and being a member of the SACP.[2][20] Just as Rosa Burger in the novel visits family in prison, so Gordimer visited her friend.[12] Later in 1986, Gordimer gave evidence at the Delmas Treason Trial in support of 22 ANC members accused of treason. She was a member of the ANC while it was still an illegal organization in South Africa, and hid several ANC leaders in her own home to help them evade arrest by the security forces.[2][13]

The inspiration for Burger's Daughter came when Gordimer was waiting to visit a political detainee in prison, and amongst the other visitors she saw a school girl, the daughter of an activist she knew. She wondered what this child was thinking and what family obligations were making her stand there.[8] The novel opens with the same scene: a 14-year-old Rosa Burger waiting outside a prison to visit her detained mother.[21] Gordimer said that children like these, whose activist parents were frequently arrested and detained, periodically had to manage entire households on their own, and it must have changed their lives completely. She stated that it was these children who encouraged her to write the book.[22]

Burger's Daughter took Gordimer four years to write, starting from a handful of what she called "very scrappy notes", "half sentences" and "little snatches of dialogue".[23] Collecting information for the novel was difficult because at the time little was known about South African communists. Gordimer relied on clandestine books and documents given to her by confidants, and her own experiences of living in South Africa.[24] Once she got going, she said, writing the book became an "organic process".[23] The Soweto riots in 1976 happened while she was working on the book, and she changed the plot to incorporate the uprising. Gordimer explained that "Rosa would have come back to South Africa; that was inevitable", but "[t]here would have been a different ending".[25] During those four years she also wrote two non-fiction articles to take breaks from working on the novel.[23]

Gordimer remarked that, more than just a story about white communists in South Africa, Burger's Daughter is about "commitment" and what she as a writer does to "make sense of life".[23] After Mandela and Fischer were sentenced in the mid-1960s, Gordimer considered going into exile, but she changed her mind and later recalled "I wouldn't be accepted as I was here, even in the worst times and even though I'm white".[13] Just as Rosa struggles to find her place as a white in the anti-apartheid liberation movement, so did Gordimer. In an interview in 1980, she said that "when we have got beyond the apartheid situation—there's a tremendous problem for whites, unless whites are allowed in by blacks, and unless we can make out a case for our being accepted and we can forge a common culture together, whites are going to be marginal".[26]

Publication and banning

Gordimer knew that Burger's Daughter would be banned in South Africa.[12] After the book was published in London by Jonathan Cape in June 1979,[27] copies were dispatched to South Africa, and on 5 July 1979 the book was banned from import and sale in South Africa.[28] The reasons given by the Publications Control Board included "propagating Communist opinions", "creating a psychosis of revolution and rebellion", and "making several unbridled attacks against the authority entrusted with the maintenance of law and order and the safety of the state".[9]

In October 1979 the Publications Appeal Board, on the recommendation of a panel of literary experts and a state security specialist, overruled the banning of Burger's Daughter.[28] The state security specialist reported the book posed no threat to the security of South Africa, and the literary experts had accused the censorship board "of bias, prejudice, and literary incompetence", and that "[i]t has not read accurately, it has severely distorted by quoting extensively out of context, it has not considered the work as a literary work deserves to be considered, and it has directly, and by implication, smeared the authoress [sic]."[28] Notwithstanding the unbanning, the chairman of the Appeal Board told a press reporter, "Don't buy [the book]—it is not worth buying. Very badly written ... This is also why we eventually passed it."[30] The Appeal Board described the book as "one-sided" in its attack on whites and the South African Government, and concluded, "As a result ... the effect of the book will be counterproductive rather than subversive."[30]

Gordimer's response to the novel's unbanning was, "I was indifferent to the opinions of the original censorship committee who neither read nor understood the book properly in the first place, and to those of the committee of literary experts who made this discovery, since both are part of the censorship system."[30] She attributed the unbanning to her international stature and the "serious attention" the book had received abroad.[23] A number of prominent authors and literary organisations had protested the banning, including Iris Murdoch, Heinrich Böll, Paul Theroux, John Fowles, Frank Kermode, The Association of American Publishers and International PEN.[30] Gordimer objected to the unbanning of the book because she felt the government was trying placate her with "special treatment", and said that the same thing would not have happened had she been black.[31] But she did describe the action as "something of a precedent for other writers" because in the book she had published a copy of an actual pamphlet written and distributed by students in the 1976 Soweto uprising,[19] which the authorities had banned. She said that similar "transgressions" in the future would be difficult for the censors to clamp down on.[23]

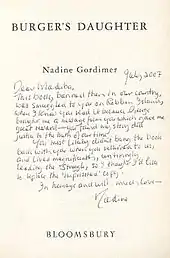

While Burger's Daughter was still banned in South Africa, a copy was smuggled into Nelson Mandela's prison cell on Robben Island, and later a message was sent out saying that he had "thought well of it".[3] Gordimer said, "That means more to me than any other opinion it could have gained."[3] Mandela also requested a meeting with her, and she applied several times to visit him on the Island, but was declined each time. She was, however, at the prison gates waiting for him when he was released in 1990,[20] and she was amongst the first he wanted to talk to.[32] In 2007 Gordimer sent Mandela an inscribed copy of Burger's Daughter to "replace the 'imprisoned' copy", and in it she thanked him for his opinion of the book, and for "untiringly leading the struggle".[33]

What Happened to Burger's Daughter

To voice her disapproval of the banning and unbanning of the book, Gordimer published What Happened to Burger's Daughter or How South African Censorship Works, a book of essays written by her and others.[34] It was published in Johannesburg in 1980 by Taurus, a small underground publishing house established in the late-1970s to print anti-apartheid literature and other material South African publishers would avoid for fear of censorship. Its publications were generally distributed privately or sent to bookshops to be given to customers free to avoid attracting the attention of the South African authorities.[12][30]

What Happened to Burger's Daughter has two essays by Gordimer and one by University of the Witwatersrand law professor John Dugard. Gordimer's essays document the publication history and fate of Burger's Daughter, and respond to the Publications Control Board's reasons for banning the book. Dugard's essay examines censorship in South Africa within the country's legal framework. Also included in the book is the Director of Publications's communiqué stating its reasons for banning the book, and the reasons for lifting the ban three months later by the Publications Appeal Board.[35]

Publication history

Burger's Daughter was first published in the United Kingdom, in hardcover, in June 1979 by Jonathan Cape, and October that year in the United States, also in hardcover, by Viking Press. The first paperback edition was published in the United Kingdom in November 1980 by Penguin Books. A unabridged 12-hour-51-minute audio cassette edition, narrated by Nadia May, was released in the United States in July 1993 by Blackstone Audio.[1]

Burger's Daughter has been translated into several other languages since its first publication in English in 1979:[36]

| Year first published | Language | Title | Translator(s) | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Danish | Burgers datter | Finn Holten Hansen | Gyldendal (Copenhagen) |

| 1979 | German | Burgers Tochter | Margaret Carroux | S. Fischer Verlag (Frankfurt) |

| 1979 | Hebrew | Bito shel burger | Am Oved (Tel-Aviv) | |

| 1979 | Italian | La figlia di Burger | Ettore Capriolo | Mondadori (Milan) |

| 1979 | Norwegian | Burgers datter | Ingebjørg Nesheim | Gyldendal Norsk Forlag (Oslo) |

| 1980 | Finnish | Burgerin tytär | Seppo Loponen; Juha Vakkuri | Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö (Helsinki) |

| 1980 | Swedish | Burgers dotter | Annika Preis | Bonnier (Stockholm) |

| 1982 | Dutch | Burger's dochter | Dorinde van Oort | Arbeiderspers (Amsterdam) |

| 1982 | French | La fille de Burger | Guy Durand | Albin Michel (Paris) |

| 1985 | Greek | Hē korē tou Mpertzer | A Dēmētriadēs; B Trapalēs; Soula Papaïōannou | Ekdoseis Odysseas (Athens) |

| 1986 | Catalan | La filla de Burger | Mercè López Arnabat | Edicions 62 (Barcelona) |

| 1986 | Spanish | La hija de Burger | Iris Menéndez | Tusquets (Barcelona) |

| 1987 | Slovenian | Burgerjeva hči | Janko Moder | Založba Orzorja (Maribor) |

| 1992 | Arabic | Ibnat Bīrgir | Dār al-Hilāl (al-Qāhirah) | |

| 1992 | Portuguese | A filha de Burger | J Teixeira de Aguilar | Edições ASA (Porto Codex) |

| 1996 | Japanese | Bāgā no musume | Fujio Fukushima | Misuzushobō (Tokyo) |

| 2008 | Polish | Córka Burgera | Paweł Cichawa | Wydawnictwo Sonia Draga (Katowice) |

Style

— Rosa's internal monologue, Burger's Daughter, page 16[37]

The narrative mode of Burger's Daughter alternates between Rosa Burger's internal monologues and the anonymous narrator, whom Gordimer calls "Rosa's conscious analysis, her reasoning approach to her life and to this country, and ... my exploration as a writer of what she doesn't know even when she thinks she's finding out".[38] Abdul R. JanMohamed, professor of English and African American Literature at Emory University,[39] calls this change of perspective a "stylistic bifurcation",[40] which allows the reader to see Rosa from different points of view, rendering her a complex character who is full of contradictions.[41] The two narratives, the subjective and the objective viewpoints, complement each other. JanMohamed explains that while the objective, third-person narrative is factual and neutral, the subjective first-person narrative, Rosa's voice, is intense and personal. Rosa's monologues are directed towards Conrad, her lover, in the first part of the story, her father's former wife, Katya, while Rosa is in France, and her father after she returns to South Africa. Because her imagined audience is always sympathetic and never questions her, Rosa's confessions are honest and open.[42]

According to academic Robin Ellen Visel, Rosa is a complicated person, with roles thrust on her by her parents, which suppresses her own goals and desires. Gordimer explained how she constructed the book's narrative structure to convey this struggle and explain Rosa: "[T]he idea came to me of Rosa questioning herself as others see her and whether what they see is what she really is. And that developed into another stylistic question—if you're going to tell the book in the first person, to whom are you talking?"[43] This led to Gordimer creating Conrad and Katya for Rosa to use as sounding boards to question and explain herself.[44]

Irene Kacandes, professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature at Dartmouth College, calls Rosa's internal monologues apostrophes, or "intrapsychic witnessing",[45] in which "a character witnesses to the self about the character's own experience".[46] Kacandes points out that Rosa believes she would not be able to internalise anything if she knew someone was listening. In an apostrophe addressed to Conrad, Rosa remarks, "If you knew I was talking to you I wouldn't be able to talk".[37] But because Rosa is not vocalising her monologues, no one can hear her, and she is able to proceed with her self-analysis unhindered. Kacandes says "Rosa imagines an interlocutor and then occupies that place herself."[47]

Gordimer uses quotation dashes to punctuate her dialogue in Burger's Daughter instead of traditional quotation marks. She told an interviewer in 1980 that readers have complained that this sometimes makes it difficult to identify the speaker, but she added "I don't care. I simply cannot stand he-said/she-said anymore. And if I can't make readers know who’s speaking from the tone of voice, the turns of phrase, well, then I've failed."[23]

Sometimes he was not asleep when he appeared to be. —What was your song?—

—Song?— Squatting on the floor cleaning up crumbs of bark and broken leaf.

—You were singing.—

—What? Was I?— She had filled a dented Benares brass pot with loquat branches.

—For the joy of living.—

She looked to see if he were making fun of her. —I didn't know.—

—But you never doubted it for a moment. Your family.—

She did not turn to him that profile of privacy with which he was used to meeting. —Suppose not.—

<small>—Conversation between Rosa and Conrad after her father had died, Burger's Daughter, page 41</small>[48]

Visel says that the use of dashes for dialogue "conveys the sense of conversation set within the flow of memory" and "is congruent with the sense of Rosa speaking essentially to herself, speakers and listeners in her conversations being dead or unreachable."[49]

Genre

Some commentators have classified Burger's Daughter as a political and historical novel. In their book Socialist Cultures East and West: A Post-Cold War Reassessment, M. Keith Booker and Dubravka Juraga call Gordimer's work one of the "representative examples of African historical novels", saying that it is an "intense engagement with the history of apartheid in South Africa".[50] Academic Robert Boyers calls it "one of the best political novels of our period",[51] and an historical novel because of its "retrospective homage to generations past".[52] Gordimer herself described Burger's Daughter as "an historical critique",[25] and a political novel, which she defines as a work that "explicates the effects of politics on human lives and, unlike a political tract, does not propagate an ideology".[53]

Visel calls the novel "fictionalised history" that shadows the history of anti-apartheid activism in South Africa, from 1946 and the African Mine Workers' Strike (Lionel and Cathy's marriage), to 1977 and the clampdown on dissidents (Rosa's detention).[54] Other notable events include the coming to power of the National Party in 1948 (Rosa's year of birth), the Treason Trial of Nelson Mandela and others in 1956, the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, and the Soweto uprising in 1976 (Rosa's return to South Africa).[54] Dominic Head writes in his book Nadine Gordimer that in Burger's Daughter "the life of ... Rosa ... runs in parallel with the history of modern South Africa".[55]

Several critics have called Burger's Daughter a Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story,[56][57][58] although not the traditional ones which, according to Susan Gardner in her essay "Still Waiting for the Great Feminist Novel", are dominated by male protagonists.[59] While Gordimer was not a feminist author and Burger's Daughter is not a feminist novel,[60] Gardner suggests that the book has "a discernible woman-concerned subtext", making it "impossible for feminists to dismiss or ignore".[59] She says it has "a potential feminist awareness" that is "obscured by more conventional patriarchal writing codes".[59] Yelin writes that after the death of Rosa's mother, the statement "Already she had taken on her mother's role in the household, giving loving support to her father"[61] illustrates "the continuing hegemony of bourgeois-patriarchal ideology" in the novel.[62] Yelin suggests that this inconsistency is responsible for Rosa's struggle, the "contradiction between feminism (Rosa's liberation as a woman) and the struggle for justice in South Africa".[62]

Themes

Gordimer says Rosa's role in society is imprinted on her from a young age by her activist parents,[63] and she grows up in the shadow of her father's political legacy.[64] Scholar Carol P. Marsh-Lockett writes that everyone sees Rosa as Lionel Burger's daughter with duties and responsibilities to her father, and not Rosa the individual. In fulfilling these expectations, she denies herself an identity of her own.[10] JanMohamed says it is only when Conrad encourages her to look beyond her self-sacrifices that Rosa starts examining the conflicts in her life, namely her commitment to help others versus her desire for a private life.[65] In an attempt to resolve these conflicts, Rosa contemplates turning to blacks, but she is wary of this because, according to the book's anonymous narrator, white South Africans tend to use blacks as a way "of perceiving sensual redemption, as romantics do, or of perceiving fears, as racialists do".[66] JanMohamed notes that Rosa's father was a romantic who established genuine friendships with blacks to overcome his "sensual redemption", but she is unsure of where she stands.[67] Visel says that Rosa's only way to free herself from these commitments to her family and the revolution is to "defect"[68] and go to France.[69] John Cooke, in his essay "Leaving the Mother's House", notes that "By putting her defection in such stark terms, Gordimer makes her strongest statement of the need, whatever the consequence, of a child to claim a life of her own".[70]

Many of Gordimer's works have explored the impact of apartheid on individuals in South Africa.[8] Journalist and novelist George Packer writes that, as in several of her novels, a theme in Burger's Daughter is of racially divided societies in which well-meaning whites unexpectedly encounter a side of black life they did not know about.[71] Literary critic Carolyn Turgeon says that while Lionel was able to work with black activists in the ANC, Rosa discovers that with the rise of the Black Consciousness Movement, many young blacks tend to view white liberals as irrelevant in their struggle for liberation.[8] Rosa witnesses this first hand listening to the black university student in Soweto (Duma Dhladhla) and, later, in London, her childhood friend "Baasie" (Zwelinzima Vulindlela), who both dismiss her father as unimportant.[8]

Author and academic Louise Yelin says that Gordimer's novels often feature white South Africans opposed to apartheid and racism who try to find their place in a multiracial society. Gordimer suggested options for whites in a 1959 essay "Where Do Whites Fit In?", but the rise of Black Consciousness in the 1970s[17] questioned whites' involvement in the liberation struggle.[72] Stephen Clingman has suggested in The Novels of Nadine Gordimer: History from the Inside that Burger's Daughter is Gordimer's response to the Black Consciousness Movement and an investigation into a "role for whites in the context of Soweto and after".[73]

Gordimer wrote in an essay in What Happened to Burger's Daughter that "The theme of my novel is human conflict between the desire to live a personal, private life, and the rival claim of social responsibility to one's fellow men".[74] Dominic Head says that Gordimer's novels often experiment with the relation of "public and private realms", and that Burger's Daughter "represents one of the peaks in this experimentation".[55] Boyers notes that the theme of "public and private", and the relation between them, is balanced in the book "so as to privilege neither one not the other".[75]

According to Packer, another common theme in Gordimer's novels is the choices ordinary people who live in oppressive regimes are forced to make.[71] Literary critics Turgeon and Carli Coetzee explain that when she realises that whites are not always welcome in the anti-apartheid liberation movements, Rosa repudiates her father's struggle and leaves the country.[8][64] Marsh-Lockett says that part of Rosa's struggle is forging her own identity,[10] and this decision to rebel against her dead father is a bold step, although she does return later to South Africa to become a committed activist and ultimately a political prisoner.[76] But, according to Coetzee, what Rosa achieves is what her father never could: to have a life of her own while still remaining politically committed.[64]

Reception

Burger's Daughter was generally well-received by critics. Anthony Sampson, a British writer, journalist and former editor of Drum, a magazine in Johannesburg in the 1950s, wrote in The New York Times that this is Gordimer's "most political and most moving novel".[4] He said that its "political authenticity" set in the "historical background of real people" makes it "harshly realistic", and added that the blending of people, landscapes and politics remind one of the great Russian pre-revolutionary novels.[4] In The New York Review of Books, Irish politician, writer and historian Conor Cruise O'Brien compared Gordimer's writing to that of Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, and described Burger's Daughter as "elegant" and "fastidious" and belonging to a "cultivated upper class".[5] He said this style is not at odds with the subject matter of the story because Rosa Burger, daughter of a revolutionary, believes herself to be an "aristocrat of the revolution".[5]

Tess Lemmon writing in the New Internationalist magazine called Burger's Daughter "arguably [Gordimer's] best novel", and complimented her on her characterisation, attention to detail, and ability to blend "the personal and the political".[77] Lemmon noted that the book's "subtle, lyrical writing" brings the reader into the characters' minds, which "is an enlivening but uncomfortable place to be".[77] In a review of Gordimer's 1980 story collection, A Soldier's Embrace in The New York Times Book Review, American novelist and critic A. G. Mojtabai stated that despite the troubled times Gordimer lived through at the time she wrote Burger's Daughter, she remained "subdued" and "sober", and even though she "scarcely raise[d] her voice", it still "reverberate[d] over a full range of emotion".[78]

In a review of the book in World Literature Today, Sheila Roberts said that Gordimer's mixture of first- and third-person narrative is "an interesting device" which is "superbly handled" by the author.[79] She commented that it allows the reader to get inside Rosa, and then step back and observe her from a distance. Roberts described Gordimer's handling of Rosa's predicament, continuing the role her father had given her versus abandoning the struggle and finding herself, as "extremely moving and memorable".[79] In The Sewanee Review Bruce King wrote that Burger's Daughter is a "large, richly complex, densely textured novel".[80] He said that it "fill[s] with unresolvable ironies and complications" as Gordimer explores the dilemmas faced by her characters in the South African political landscape.[80]

American writer Joseph Epstein had mixed feelings about the book. He wrote in The Hudson Review that it is a novel that "gives scarcely any pleasure in the reading but which one is pleased to have read nonetheless".[6] Epstein complained about it being "a mighty slow read" with "off the mark" descriptions and "stylistic infelicities".[6] He felt that big subjects sometimes "relieve a novelist of the burdens of nicety of style".[6] Epstein said that reading the book is like "looking at a mosaic very close up, tile by tile", and that the big picture only emerges near the end.[6] But he complimented Gordimer on the way in which she unravels Rosa's fate, saying that it is "a tribute to her art".[6]

Honours and awards

Despite being banned in South Africa, Burger's Daughter won the 1980 Central News Agency (CNA) Literary Award, a prominent literary award in that country.[28][81] In 1991 Gordimer was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for her works of "intense immediacy" and "extremely complicated personal and social relationships in her environment".[82] During the award ceremony speech by Sture Allén, Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, Burger's Daughter was cited as one of Gordimer's novels in which "artistry and morality fuse".[83]

In 2001 the novel was named one of South Africa's top 10 books in The Guardian in the United Kingdom by author Gillian Slovo, daughter of South African anti-apartheid activists Joe Slovo and Ruth First.[84] Following Gordimer's death in 2014, The Guardian and Time magazine put Burger's Daughter in their list of the top five Gordimer books.[85][86] Indian writer Neel Mukherjee included Burger's Daughter in his 2015 "top 10 books about revolutionaries", also published in The Guardian.[87]

Notes

- Rosa's full name is Rosa Marie Burger, which comes from Rosa Luxemburg, the revolutionary socialist, and Rosa's grandmother, Marie Burger.[7]

- In South Africa, as a sign of respect and affection, Nelson Mandela is referred to by many as the "Father of the Nation", and is often called "Madiba", after his Xhosa clan name.[29]

References

- "Burger's Daughter". FantasticFiction. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Wästberg, Per (26 April 2001). "Nadine Gordimer and the South African Experience". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Gordimer, Nadine. "Nadine Gordimer's key note speech – Amnesty International Ambassador of Conscience Award, Nelson Mandela". Novel Rights. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- Sampson, Anthony (19 August 1979). "Heroism in South Africa". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2018. (registration required)

- O'Brien, Conor Cruise (25 October 1979). "Waiting for Revolution". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Epstein, Joseph (1980). "Too Much Even of Kreplach". The Hudson Review. 33 (1): 97–110. doi:10.2307/3850722. JSTOR 3850722.

- Niedzialek, Ewe (2018). "The Desire of Nowhere - Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter in a Trans-cultural Perspective". Colloquia Humanistica. Instytut Slawistyki Polskiej Akademii Nauk (7): 40–41. doi:10.11649/ch.2018.003.

- Turgeon, Carolyn (1 June 2001). "Burger's Daughter". In Moss, Joyce (ed.). World Literature and Its Times: Profiles of Notable Literary Works and the Historical Events That Influenced Them. Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-3729-3. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- Gardner 1990, p. 161.

- Marsh-Lockett 2012, p. 193.

- "Background: Bram Fischer". University of the Witwatersrand School of Law. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Nadine Gordimer Interview (page 1)". Academy of Achievement. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Steele, Jonathan (27 October 2001). "White magic". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- De Lange 1997, p. 82.

- Yelin 1991, p. 221.

- Wilson, Ilse (18 July 2014). "At home with Nadine Gordimer, a very private individual". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- De Lange 1997, p. 83.

- Gordimer 1979, pp. 24–27.

- Gordimer 1979, pp. 346–347.

- "Nadine Gordimer Interview (page 5)". Academy of Achievement. 11 November 2009. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 9.

- Cooke 2003, p. 84.

- Hurwitt, Jannika (1983). "Nadine Gordimer, The Art of Fiction No. 77". The Paris Review. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- "She's a Thorn in Side of South Africa". Indiana Gazette. 28 September 2000. p. 35. Retrieved 4 June 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gray 1990, p. 182.

- Gardner 1990, p. 168.

- Mitgang, Herbert (19 August 1979). "The Authoress". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- Karolides 2006, p. 72.

- "Nelson Mandela discharged from South Africa hospital". BBC News. 6 April 2013. Archived from the original on 9 April 2013. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Roberts, Sheila (1982). "What Happened to Burger's Daughter or How South African Censorship Works by Nadine Gordimer". Research in African Literatures. 13 (2): 259–262. JSTOR 3818653.

- Kirsch, Adam (30 July 2010). "Letters From Johannesburg". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Nadine Gordimer Biography". Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "Inscription: Burger's Daughter". Nelson Mandela Archives. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Gray 1990, p. 177.

- Lasker, Carrol (1981). "What Happened to Burger's Daughter, or How South African Censorship Works by Nadine Gordimer; John Dugard; Richard Smith". World Literature Today. 55 (1): 167. doi:10.2307/40135909. JSTOR 40135909.

- All editions for Burger's Daughter. OCLC 5834280.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 16.

- Gray 1990, p. 178.

- Williams, Kimber (18 December 2012). "New English department hires expand, enrich offerings". Emory University. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- JanMohamed 1983, p. 128.

- Green, Robert (1988). "From "The Lying Days to July's People": The Novels of Nadine Gordimer". Journal of Modern Literature. 14 (4): 543–563. JSTOR 3831565.

- JanMohamed 1983, pp. 127–128.

- Gardner 1990, pp. 170–171.

- Visel 1987, p. 182.

- Kacandes 2001, p. 103.

- Kacandes 2001, p. 97.

- Kacandes 2001, p. 104.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 41.

- Visel 1987, pp. 180–181.

- Juraga & Booker 2002, p. 18.

- Boyers 1984, p. 65.

- Boyers 1984, p. 67.

- Yelin 1998, pp. 126–127.

- Visel 1987, pp. 200–201.

- Head 1994, p. 15.

- Visel 1987, p. 179.

- Marsh-Lockett 2012, p. 192.

- Gardner 2003, p. 177.

- Gardner 2003, p. 173.

- Gardner 2003, p. 181.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 12.

- Yelin 1991, p. 222.

- Gardner 1990, p. 170.

- Coetzee, Carli (1999). "Burger's Daughter (1979)". The Cambridge Guide to Women's Writing in English. Retrieved 20 June 2013 – via Credo.

- JanMohamed 1983, pp. 126–127.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 135.

- JanMohamed 1983, p. 132.

- Gordimer 1979, p. 264.

- Visel 1987, p. 186.

- Cooke 2003, p. 91.

- Packer, George (17 December 1990). "My Son's Story". The Nation. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2012 – via HighBeam.

- Yelin 1998, p. 111.

- Clingman 1993, pp. 7,170.

- Gordimer 1980, p. 20.

- Boyers 1984, p. 66.

- "Burger, Rosa". Chambers Dictionary of Literary Characters. 2004. Retrieved 20 June 2013 – via Credo.

- Lemmon, Tess (November 1989). "Burger's Daughter". New Internationalist (201). Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Mojtabai, A. G. (24 August 1980). "Her Region is Ours". The New York Times Book Review. pp. 7, 18.

- Roberts, Sheila (1982). "Burger's Daughter by Nadine Gordimer; A Soldier's Embrace by Nadine Gordimer". World Literature Today. 56 (1): 167–168. doi:10.2307/40137154. JSTOR 40137154.

- King, Bruce (1981). "Keneally, Stow, Gordimer, and the New Literatures". The Sewanee Review. 89 (3): 461–469. JSTOR 27543883.

- Marsh-Lockett 2012, p. 197.

- "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1991: Press Release". nobelprize.org. 3 October 1991. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Allén, Sture (1991). "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1991: Award Ceremony Speech". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Slovo, Gillian (12 January 2012). "Gillian Slovo's top 10 South African books". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Armitstead, Claire (14 July 2014). "Nadine Gordimer: five must-read books". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Rothman, Lily (15 July 2014). "Nadine Gordimer: 5 Essential Reads from the Award-Winning Author". Time. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Mukherjee, Neel (14 January 2015). "Neel Mukherjee's top 10 books about revolutionaries". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

Works cited

- Boyers, Robert (1984). "Public and Private: On Burger's Daughter". Salmagundi (62): 62–92. JSTOR 40547638.

- Clingman, Stephen (1993). The Novels of Nadine Gordimer: History from the Inside. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. ISBN 978-0-7475-1390-2.

- Cooke, John (2003). "Leaving the Mother's House". In Newman, Judie (ed.). Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 81–98. ISBN 978-0-19-514717-9.

- De Lange, Margreet (1997). The Muzzled Muse: Literature and Censorship in South Africa. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-2220-6.

- Gardner, Susan (1990). "A Story for This Place and Time: An Interview with Nadine Gordimer about Burger's Daughter". In Bazin, Nancy Topping; Seymour, Marilyn Dallman (eds.). Conversations with Nadine Gordimer. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 161–175. ISBN 978-0-87805-444-2.

- Gardner, Susan (2003). "Still Waiting for the Great Feminist Novel". In Newman, Judie (ed.). Nadine Gordimer's Burger's Daughter: A Casebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 167–220. ISBN 978-0-19-514717-9.

- Gordimer, Nadine (1979). Burger's Daughter. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-224-01690-2.

- Gordimer, Nadine (1980). "What the Book is About". In Gordimer, Nadine; et al. (eds.). What Happened to Burger's Daughter or How South African Censorship Works. Johannesburg: Taurus. ISBN 978-0-620-04482-0.

- Gray, Stephen (1990). "An Interview with Nadine Gordimer". In Bazin, Nancy Topping; Seymour, Marilyn Dallman (eds.). Conversations with Nadine Gordimer. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 176–184. ISBN 978-0-87805-444-2.

- Head, Dominic (10 November 1994). Nadine Gordimer. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47549-5.

- JanMohamed, Abdul R. (1983). Manichean Aesthetics: The Politics of Literature in Colonial Africa. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 126–139. ISBN 978-0-87023-395-1. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- Juraga, Dubravka; Booker, M. Keith (2002). Socialist Cultures East and West: A Post-Cold War Reassessment. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-275-97490-9.

- Kacandes, Irene (2001). Talk Fiction: Literature and the Talk Explosion. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2738-5. Retrieved 13 June 2013 – via Questia.

- Karolides, Nicholas J. (2006). Literature Suppressed on Political Grounds. New York City: Infobase Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-8160-7151-7.

- Marsh-Lockett, Carol P. (2012). "Nadine Gordimer (1923–)". In Jagne, Siga Fatima; Parekh, Pushpa Naidu (eds.). Postcolonial African Writers: A Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. pp. 187–200. ISBN 978-1-136-59397-0 – via Questia.

- Visel, Robin Ellen (1987). White Eve in the "petrified Garden": The Colonial African Heroine in the Writing of Olive Schreiner, Isak Dinesen, Doris Lessing and Nadine Gordimer. University of British Columbia. pp. 179–202. ISBN 978-0-315-44684-7.

- Yelin, Louise (1991). "Problems of Gordimer's Poetics: Dialogue in Burger's Daughter". In Bauer, Dale M.; Mckinstry, Susan Jaret (eds.). Feminism, Bakhtin, and the Dialogic. State University of New York Press. pp. 219–238. ISBN 978-0-7914-9599-5. Retrieved 12 June 2013 – via Questia.

- Yelin, Louise (1998). From the Margins of Empire: Christina Stead, Doris Lessing, Nadine Gordimer. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8505-3.