Burtis–Kimball House Hotel/Burtis Opera House

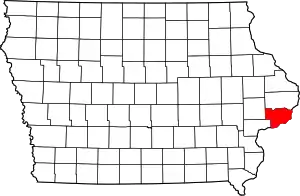

The Burtis–Kimball House Hotel and the Burtis Opera House were located in downtown Davenport, Iowa, United States. The hotel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.[1] It has since been torn down and it was delisted from the National Register in 2008.[3] The theatre building has been significantly altered since a fire in the 1920s. Both, however, remain important to the history of the city of Davenport.

Burtis–Kimball House Hotel | |

Formerly listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

Undated photo showing the opera house to the left and the hotel on the right. | |

| |

| Location | 210 E. 4th Street Davenport, Iowa |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°31′25″N 90°34′20″W |

| Area | less than acre |

| Built | 1874 |

| Architect | Frederick G. Clausen |

| Architectural style | Italianate Second Empire |

| NRHP reference No. | 79003696[1] |

Thomas Cusack Co. District Headquarters | |

| Built | 1867, 1922 |

| Built by | John Soller & Sons |

| Architect | Zimmerman, Saxe & Zimmerman |

| Architectural style | Renaissance Revival |

| Part of | Davenport Downtown Commercial Historic District (ID100005546[2]) |

| Added to NRHP | September 11, 2020 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | April 2, 1979 |

| Removed from NRHP | September 10, 2008[3] |

Burtis–Kimball House Hotel

The first phase of hotel construction in Davenport lasted from 1836, when the city was founded, until just before the Civil War. Most of these hotels were small and were located near the Mississippi River to take advantage of the passengers disembarking from the riverboats.[4] The second phase marked the arrival of the railroad when the first bridge to cross the Mississippi was opened between Rock Island, Illinois and Davenport in 1856.[5] Two years later J.J. Burtis, who had operated the LeClaire House in Davenport, opened his own hotel. It had an entrance on the mainline of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad. The hotel rose to prominence in 1861 when Iowa Governor Samuel Kirkwood made the hotel his Civil War headquarters as the telegraph lines did not extend any further west.[6]

A new railroad bridge replaced the original one in 1872, and Burtis built a new hotel along the new mainline of the railroad at Fourth and Perry Streets in 1874. The block was already the site of the Burtis Opera House. The new hotel featured its own train platform[4] as well as telephone, telegraph, and an elevator. In 1880 the name of the hotel was changed to the Kimball House and it was advertised as the "largest and best hotel in Iowa."[6] After 1900 the Kimball House was eclipsed by the third phase of hotel building in the city that included the Hotel Davenport, the Hotel Blackhawk, and the Hotel Mississippi.

The hotel was transformed into an apartment building and renamed the Perry Apartments. Future US President Ronald Reagan lived in the building when he worked for radio station WOC from 1932–1933.[7] In 1939 the building was heavily damaged by fire. Bill Vale was paid $5,000 to tear it down, and then bought the property for $25,000.[8] He put in bout $12,000 in repairs, and renamed the building the Vale Apartments. As time went on the building started to decline. While attempts were made to save it, the building had become structurally unsafe and was torn down in 1993.[9]

Burtis Opera House

The Burtis Opera House was opened in Davenport in 1867 at 415 Perry Street.[10] The theater could hold an audience of 1,600 and it was a widely used facility. Mark Twain spoke to a sold-out house on his "The American Vandal Abroad" tour in 1869.[11] In March 1874 Susan B. Anthony lectured on the woman's right to vote.[11] Al Jolson performed on the stage years after he worked as a singing waiter at Brick Munro's Pavilion in Bucktown.[12] The Quad City Symphony Orchestra played its first concert as the Tri-City Symphony in the Burtis on March 29, 1916.[13]

The Burtis was an elegant building constructed in the Second Empire style.[10] It featured a mansard roof with heavily hooded dormer windows. A bracketed cornice defined the transition from the roofline to wall elevation. A projecting pavilion with its own mansard roof contained the building's main entrance in the center of the façade.

On April 26, 1921, an arsonist set fire to the building and it was largely destroyed.[14] Charles T. Kindt, the building's owner and operator of the opera house, had the damaged building remodeled for the Thomas Cusack Company, an outdoor advertising firm from Chicago. Kindt was the was district manager of the firm's Davenport branch. The Chicago architectural firm of Zimmerman, Saxe & Zimmerman designed the building's renovation, which was built by John Soller & Sons. Zimmerman worked nationally for Cusack, the world's largest outdoor ad firm at the time.[15] The building's appearance was altered in the rebuilding process. The third story with its mansard roof, as well as the second floor, were not retained. The pilasters on the corners were shortened and a simple cornice was added across the top. The roof is flat and a raised parapet defines the main entrance. The arched windows that flanked the center pavilion were retained in an altered form. The building's style now resembles the Renaissance Revival style.

By 1925 the building housed the General Outdoor Advertising Company.[10] It was later occupied by a VFW post and state offices. The building stands on its own next to the raised railroad tracks since the Kimball House/Vale Apartments and the rail station have been torn down. Tri-City Electric occupied the building for several years before the United States Department of Veteran Affairs. In 2020 the building was included as a contributing property in the Davenport Downtown Commercial Historic District as the Thomas Cusack Co. District Headquarters.[15]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 24, 2008.

- "National Register of Historic Places Program: Weekly List". National Park Service. September 25, 2020. Retrieved 2020-09-25.

- "Weekly List". National Park Service. September 19, 2008. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- "Historic Preservation in Davenport, Iowa". City of Davenport. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- Svendsen, Marlys A.; Bowers, Martha H. (1982). Davenport where the Mississippi runs west: A Survey of Davenport History & Architecture. Davenport, Iowa: City of Davenport. p. 3.3.

- Svendsen & Bowers 1982, p. 5.6.

- Bill Wundram (June 5, 2004). "Visiting the room where Reagan slept". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- Bill Wundram (September 22, 1992). "The veil behind the Vale". Quad-City Times. Davenport, Iowa. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Bill Wundram (January 31, 1993). "January: The best (and worst) of times". Quad-City Times. Davenport. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- "Burtis Opera House" (PDF). Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- Anderson, Fredrick I. (ed.) (1982). Joined by a River: Quad Cities. Davenport: Lee Enterprises. p. 76.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Wundram, Bill (1999). A Time We Remember: Celebrating a Century in our Quad-Cities. Davenport, Iowa: Quad-City Times. p. 125.

- "The Quad-City Symphony Orchestra". Davenport Public Library. Archived from the original on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2010-11-09.

- Anderson 1982, p. 171.

- Jennifer Irsfeld James. "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form: Davenport Downtown Commercial Historic District" (PDF). Downtown Davenport, Iowa. Retrieved 2020-09-25.