Byzantine–Genoese War (1348–1349)

The Byzantine–Genoese War of 1348–1349 was fought over control over custom dues through the Bosphorus. The Byzantines attempted to break their dependence for food and maritime commerce on the Genoese merchants of Galata, and also to rebuild their own naval power. Their newly constructed navy however was captured by the Genoese, and a peace agreement was concluded.

| Byzantine–Genoese War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nicaean–Latin wars | |||||||

Byzantine Empire and surrounding territory in 1355, shortly after the Byzantine–Genoese War of 1348–1349. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

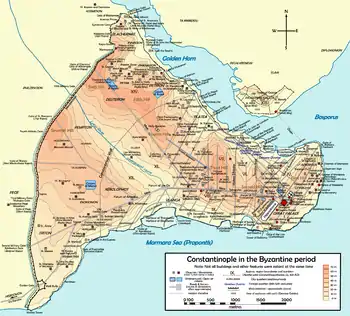

The Genoese held the colony of Galata on the Golden Horn across from the city of Constantinople since 1261 as part of the Treaty of Nymphaeum, a trade agreement between the Byzantines and Genoese. However, the dilapidated state of the Byzantine Empire following the civil war of 1341–1347 was easily shown in the control of custom duties through the strategic straights of the Bosphorus. Even though Constantinople was the Imperial seat of power with its cultural and military center on the shores of the Bosphorus, only thirteen percent of custom dues passing through the strait were going to the Empire. The remaining 87 percent was collected by the Genoese from their colony of Galata.[2] Genoa collected 200,000 hyperpyra from annual custom revenues from Galata, while Constantinople collected a mere 30,000.[3] The Byzantine navy, a notable force in the Aegean during the reign of Andronikos III Palaiologos, was completely destroyed during the civil war. Thrace, the main imperial possession besides the Despotate of the Morea, was still recovering following the destruction of marauding Turkish mercenaries during the civil war. Byzantine trade was ruined and there were few other financial reserves for the Empire other than the duties and tariffs from the Bosphorus.[3]

The conflict

In order to regain control of the custom duties, the emperor John VI Kantakouzenos made preparations to lower Constantinople's duties and most tariffs to undercut the Genoese in Galata. Still recovering from the civil war of 1341–1347, the emperor, with great difficulty, raised 50,000 hyperpyra from private sources (as the state treasury was empty) for a shipbuilding program for the expected war to come. When the tariffs and custom duties were finally lowered, merchant shipping coming through the strait bypassed Genoese Galata and diverted their ships across the Golden Horn to Byzantine Constantinople.

The Genoese, financially hard-hit from this policy, declared war on the Empire, and in August 1348, a flotilla of ships sailed across the Horn and attacked the Byzantine fleet;[4] despite their large scale preparations, the Byzantine fleet was destroyed by early 1349.[2] The Byzantines retaliated by burning wharves and warehouses along the shore and catapulted stones and burning bales of hay into Galata, setting major parts of the city on fire. After several weeks of fighting, plenipotentiaries from Genoa came and negotiated a peace agreement. The Genoese agreed to pay a war indemnity of 100,000 hyperpyra and evacuated the land behind Galata which they illegally occupied; last, they promised never to attack Constantinople. In return the Byzantines surrendered nothing, but the Genoese custom duties remained in effect.[1][4]

Aftermath

The devastation of the 1341–1347 civil war so greatly weakened the Empire that its financial reserves were irrevocably depleted. Its only recourse was to make an attempt to take control of the custom duties and tariffs of the trade route through the Bosphorus. The 1348-49 war was the last attempt by the Byzantines to retake control single-handedly. From 1350, the Byzantines allied themselves to the Republic of Venice, which was also at war with Genoa. However, as Galata remained defiant, the Byzantines were forced to settle the conflict in a compromise peace in May 1352.

Thereafter, few other financial resources remained for the Empire, which contributed to its decline and final downfall in 1453.

Notes

- Ostrogorsky states the Byzantines lost this conflict, while Norwich believes they won.

- Ostrogorsky, p.528.

- Ostrogorsky, p.526.

- Norwich, p.346

Sources

- Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State, Rutgers University Press, (1969)

- Norwich, John. A Short History of Byzantium, Alfred A. Knopf Press, New York, (1997)