Byzantine silver

Silver was important in Byzantine society as it was the most precious metal right after gold.[1] Byzantine silver was prized in both the secular and domestic realms. Aristocratic homes had silver dining ware, and in churches silver was used for crosses, liturgical vessels such as the patens and chalices required for every Eucharist.[1] Silver was also used as a medium in pagan mythological scenes and objects such as the Sevso Treasure.[1] Silver pieces, especially silverware, continued to be rendered in the classical style into the seventh century.[1]

Silver items were also controlled stamped, sometimes up to five times on a single piece, many such pieces are dated between the fourth and eighth centuries.[1] During the reign of Heraclius (r. 610-41 AD), the production of silverware halts, which coincides with the State confiscating valuable metals to help replenish the treasury during the Persian War.[1] Silver items began to regularly buried, such as the Stuma Treasure of 56 objects found in Syria during 1908, dated between 540 and 640 and attributed to the village church of St Sergios at Kaper Koraon.[1] The Sion Treasure from Lycia consists of 71 pieces with 30 pieces stamped between 550 and 565 AD [1] See Byzantine Coins for currency and monetary information.

Bowls

During the nineteenth century two silver bowls were discovered in Estonia that date to the late fifth or early sixth century period of which the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I reigned 491-518 AD.[2] The silver bowl deemed the “Kriimani” bowl, for the location in which it was found, has a rim of 15.5 cm with a height of 9 cm.[2] Two beaded bands border the rim of the bowl. Silver analysis shows 93-95% Silver, 3.5-5% Copper, and traces of Gold and Platinum.[2] The second bowl, referred to as the “Varnja Bowl,” was discovered in 1895 near the village of Varnja.[2] The Varnja bowl also has two beaded bands that circle the rim, and it is also stamped similar to the Kriimani bowl.

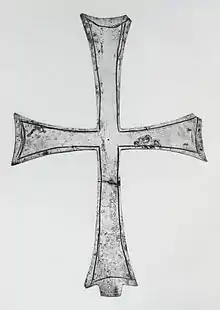

Crosses

Crosses were also lavishly adorned with precious materials and biblical scenes during the Byzantine period. Scholars refer to a cross called “The Work of Mark,” due to the monks inscriptions on the cross.[3] The cross is dated at late tenth or early eleventh century.[3] This cross is 47 cm high, 26 cm wide, and very ornamented meaning it was probably used in processions.[3] The iron core of the cross is encased in silver. Points projecting from the four arms of the cross would all have had small silver-gilt balls, which can be seen on other such crosses.[3] Traces of gilding where the balls would have been provide further evidence. On one side across the central arm are three roundels forming a deesis, which shows Christ as a central figure holding a book of gospels in his left hand and blessing with his right.[3] The Virgin Mary is shown bowing on Christ's left while St John the Baptist bows on his right [3] The roundel on the top arm portrays the Archangel Michael, while the bottom roundel portrays a figure titled St Theodore.[3] This side is heavily embossed with silver-gilt, and has a vine scroll and beaded border.[3] The reverse side does not have such borders.

The reverse has a black medium used in conjunction with the partial gilding of niello, which is an enamel type substance, in this case mixed with sulphur and silver.[3] The roundels portray saints with the top of the cross showing the evangelist St John Theologos. The arm roundels show St Peter on the left and St Paul on the right.[3] The fourth roundel shows St Basil in bishops robes.[3] The middle of the scene has Virgin Mary and her child with a standing portrait of St Constantine above them decorated in his robe.[3] The Virgin Mary has St Demetrius on the left, St Procopius on her right, and the last saint shown is St Nikitas.[3] All saints are identified by the engraving of their names above them. An inscription of a semicircular area just 3 cm wide and embedded into the front of the cross, before the tang projects, reads “‘The work of the Faithful Mark’” [3]

Similar crosses are known of such as the cross of Adrianople. This cross has frontal images of Christ and the Virgin Mary, along with archangels Michael and Gabriel on the cross arms.[3] The reverse side shows church fathers, and the donor’s name is inscribed as Sisinnios, which dates the cross to the final years of the tenth century.[3]

Another cross, in the Cleveland Museum of Art, is dated to the eleventh century due to its comparison of portraits with imperial portraits on coins and seal of that time.[3] Distribution of silver-gilt relief decoration and niello are the same on both sides.[3]

Plates

Silver pieces, and especially plates, such as the Missorium of Theodosius I of 338 AD are engraved and styled similarly to the set of nine plates showing the Life of David stamped between 613 and 630 AD.[1] The Kaiseraugst Achilles Plate has the closest similarity to the David Plates in regards to late antique silver.[4] The Achilles Plate was buried with a large hoard of domestic silver during the fourth century inside the walls of the Rhine frontier fort of Agusta Rarica, which was discovered in the early 1960s.[4] The Achiles Plate has the signature of Pausylyps of Thessalanike which places its manufacturing in the eastern Byzantine empire.[4] This is reinforced with the similar control stamps on the David Plates.[4] The large octagonal plate has decoration around its rim, and in the center a medallion shows a series of scenes of Achilles’ life before the Trojan War.[4] The Achilles Plate shows a narrative of eleven scenes on one plate.[4] The David Plates and the Achilles Plate show a tradition of late antique silver working that produced many objects between the fourth and seventh centuries with scenes from traditional Greek mythology.[4] The David Plates and Achilles Plate are very decorative, and would have been used as show pieces.[4]

References

- Cormack, Robin (2000). Byzantium Art. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-19-284211-4.

- Quast, Tamla, Dieter, Ulle (2010). "Two Fifth Century Ad Byzantine Silver Bowls from Estonia". Estonian Journal of Archeology. 14.2 (December): 99–101.

- Hetherington, Paul (2010). "The Work of Mark". Apollo (March): 92.

- Leader, Ruth (2000). "The David Plates Revisited: Transforming the Secular in Early Byzantium". Art Bulletin. 82 (September): 421–422.