Camp Grant, Arizona

Camp Grant was the name used from 1866 to 1872 for the United States military post at the confluence of the San Pedro River and Aravaipa Creek in the Arizona Territory. It is near the site of the Camp Grant massacre.

The post was first constructed in 1860, and between 1860 and 1873, the post was abandoned or destroyed and then rebuilt multiple times, and it was known by a variety of names, starting with Fort Breckinridge in 1860 before becoming Camp Grant in 1866. In 1872 The "old" Camp Grant on the San Pedro River (located in present day Pinal County) was replaced by a "new" Fort Grant at the base of Mount Graham (in present day Graham County). Little evidence of "old" Camp Grant (formerly Fort Breckinridge) is visible today.

Early names

- Camp on San Pedro River, May, 1860. A generic name used for the site during fort's initial construction phase.[1]

- Fort Aravaipa, or Fort Aravaypa [sic], 1860. Name used for post for a few months after construction, until an official name was designated.[1][2]

- Fort Breckinridge, August 1860 to 1861. Following construction the fort was officially named for the then-serving Vice President of the United States, John C. Breckinridge and this was the official name of the post during and after the time the post was destroyed and the site abandoned, following removal of the Union garrison at the start of the Civil War.[1]

- Fort Stanford, or Camp Stanford, 1862 to 1865. Unofficial name used while California volunteer troops reoccupied the site in 1862 to 1865 as a U.S. Army post during the Civil War, in honor of then acting California governor Leland Stanford.[1]

- Fort Breckenridge, 1862 to 1865. Vice President John C. Breckinridge had "gone south" after his term of office concluded in 1861 and he accepted a commission as a General of the Confederate Army, later becoming the Secretary of War of the Confederacy. In October, 1862 the Fort was renamed Fort Breckenridge by the U.S. Army, with the slight change in spelling reflecting unhappiness with the original namesake. The fort continued to be sporadically referred to by this name, while also being referred to as Fort (or Camp) Stanford, until it became designated by the Army as Camp Grant.

- Camp on San Pedro River[3] and Camp Wright,[1] 1865. The Fort was re-constructed starting in 1865. The first few months of construction was undertaken by the 2nd Regiment California Volunteer Infantry commanded by Colonel Thomas F. Wright, and both the river location and the commander's name were used generically for the post during this brief limbo period.

- Camp Grant, 1865 to 1872. The construction of the post was completed by the U.S. Army. After the U.S. Army took over, the post was demoted from a Fort to a Camp in 1865 and officially designated "Camp Grant" honoring Ulysses Grant, of Civil War fame. The name "Camp Grant" was used for the post through 1866 when floods caused it to be relocated, and reconstructed yet again on a higher terrace above the rivers. The name "Camp Grant" continued to be used until closure in 1872 and abandonment in 1873,[1] during which time the Camp Grant Massacre occurred (1871), and a temporary Indian reservation was located in the area (1871), later moved to San Carlos.

- Fort Grant, Although the U.S. Army designated the post a "camp", not a "fort", there were still historical references which sometimes named the post as "Fort Grant". in 1872 the post was replaced by an officially designated Fort Grant which was re-located to the east under Graham peak in Graham County.

Strategic importance

In 1859, the time of the decision to found the military post on the San Pedro River at the mouth of Aravaipa Creek, the site was uniquely situated to command important avenues of then current Indian travel. This location commanded the intersection of four important routes. To the south, the San Pedro Valley stretched away into Sonora, and gave access to Mexico; this route was a vast natural highway for Apache raids into Mexico. To the west running up the Camp Grant Wash a road/trail extended over a divide toward the Santa Cruz River Valley and Tucson. To the north, only 10 miles down the valley, lay the Gila River and along it the Kearny Expedition trail extended from the Rio Grande to California. The post was placed to block the fourth route to the east, the Arivaipa Canyon connection to the San Pedro Valley. Aravaipa Creek cuts a narrow canyon completely through the Galiuro Mountains, affording a short cut access between the San Pedro Valley and the Upper Gila and the Sulphur Spring Valley. Because Arivaipa canyon cut through a mountain range and because it had wood and water all along its length, it was a much used east-west Apache travel route.[4]

Purpose

The military fort at the junction of Aravaipa Creek and the San Pedro River had the purpose of providing security for a steadily increasing stream of settlers and miners into this area of the Arizona territory, both before and after the end of the Civil War.

For more than two full centuries prior to the United States involvement in the New Mexico/Arizona area, Apache bands had been engaged in warfare to resist the Spanish advance in Northern Mexico. The Spanish employed a method of conquest in which the first step was to conquer Indian tribal groups using the horse and superior technology including steel weapons and, later, firearms. The tribe was then subjugated to a form of vassalage, very close to slavery.

The Apaches, and other Indian tribes sought to avoid this advancing subjugation by the Spanish. By their determined resistance over two centuries the surviving Indian tribes of the American southwest, but primarily the Apaches, brought the advance of the Spanish to a halt at about the border of present day U.S. and northern Mexico. In so doing they preserved a claim to a homeland, as well as their freedom. The price of this autonomy and freedom was a continuous bitter guerrilla warfare between the Indian groups and the outposts of Spanish civilization – the communities, ranches and missions in the Mexican Territories of Chihuahua, Sonora and New Mexico.[5]

As the Spanish sought to subjugate the Indian bands, their resistance was met with savage retaliation. Spanish military units marched from supply centers and went into the areas belonging to the Indians and sought out resisting tribes, and attempted to kill or captured them. Captured Indians were sold into slavery. Some tribes who resisted the Spanish were exterminated or scattered by these retaliatory responses. For those tribes that resisted the Spanish and survived, like the Apache, each side developed a traditional and virulent hatred for the other.

In conducting this never-ending warfare, the Apache become expert at conducting raids. Whenever possible they avoided involvement in pitched battle with larger groups of armed Spanish. Over two centuries raiding become the Apache's preferred method of warfare, and it also became a cultural norm and a way of life. Children were trained and individually mentored from an early age in discipline and skills critical to this type of warfare. Men and women, young and old, had roles within the Apache band that supported the raiding process.

Over the 200 years of warfare with the Spanish, raiding became the established economic basis of Apache bands. The raids literally kept them fed and provided with goods at a much higher level that could be achieved by subsistence hunting/gathering. A primary goal of the raiders was to acquire cattle, horses or mules, as well as any plunder that appeared attractive or useful. The Apache did not keep or breed herds of cattle. They did not keep and breed horses as did other plains Indians tribes. Cattle captured in raids were used for food, and mules and horses were used for both transportation and also as food. Once the captured herds were used up, the raiders went out seeking more.

The excess livestock and plunder taken in raids were traded to unscrupulous trader/merchants. The Apaches frequently made a temporary "treaty" with certain Spanish communities to trade excess goods from raids. In the trades the Apache received the goods they wanted but could not produce—clothing, certain foods, whiskey, more arms and ammunition, and other items. The persons trading with the Apache got animals and goods at low prices that they could then use or resell for a good profits. In these trading sessions, the trader sometimes resorted to treachery, lulling the Indian group into a sense of complacency (sometimes employing mescal), and then capturing them, killing those who resisted. The captives were sold into slavery.

Indians who felt wronged would then indiscriminately kill Hispanic persons, sometimes first subjecting them to torture, and would conduct or participate in raids and ambushes whose goal was retaliation/revenge more than economic gain. Over the two centuries of interaction with the Spanish the Apache bands had acquired a deep distrust of outsiders.

Following the Mexican War, for a brief time the Apache adopted the view toward the people of the United States that "the enemy of my enemy is my friend", but this did not last, and in response to the growing invasion of Anglos, and the inevitable conflicts that arose, Indian raiding parties began attacking US ranches, camps, prospectors, freighters, wagon trains, stages, immigrants and small groups and settlements of all kinds.

In conducting raids, the Apache had a very high level of expertise. They employed caution, and exercised discipline. They employed advance preparation, swift movement, and surprise, with sophisticated and well-coordinated small-unit tactics honed by generations of experience. The raiders picked their targets. They knew the country and the raids were almost always successful, after which the raiders moved swiftly from the area. If followed the raiders weighed ambush. The raiders usually killed or attempted to kill all the persons they encountered to prevent being identified, and the development of close pursuit.

During the period of the existence of a fort on the San Pedro River, from 1860 to 1872, the U.S. Army garrison was constantly occupied by responding to these raids, and pursuing and attempting to interdict and kill or capture the raiders. The Apache raiders almost always had superior knowledge of the country, and the Army sometimes did not even get a glimpse of those they pursued. However, the Army kept up pursuit, and did inflict casualties, and the resulting slow attrition of the relatively small Apache bands eventually had an impact. By 1886 the previous Apache population had become either a casualty of war, or had surrendered and was kept under close watch on reservations, often far from their homeland.

Fort Breckinridge 1860 to 1865

The United States military post at the confluence of the San Pedro River and Aravaipa Creek in Arizona Territory existed from 1860 to 1872. The post was built in May 1860 by B Company, U.S. 8th Infantry Regiment,[2] sent from the first Fort Buchanan.[6]

The Fort was sited along the San Pedro River which was a major route of travel from pre-historic times. In 1857, the Leach Wagon Road had been built to provide a freight road from New Mexico to California,[7] and part of the wagon road ran through the San Pedro valley.[8] Reportedly, Leach suggested the fort be built on the route of his wagon road to provide protection for travelers on the wagon road, as well as area settlers and emigrants.[2]

While under construction in May 1860 the post was referred to as the Camp on San Pedro River.[1] It was named Fort Aravaipa (or Aravaypa),[1] when constructed, then officially designated as Fort Breckinridge in August 1860[1][6] to honor John C. Breckinridge, vice president from 1857 to 1861 under President James Buchanan. This was the second military post in the area of the Gadsden Purchase (1853).[9]

In October 1860 150 Indian raiders ran off all of the stock of the post.[10] In February, 1861, the Fort Breckinridge troops reinforced Fort Buchanan troops during the Bascom Affair. After the outbreak of the American Civil War the army determined to move the post's regular troops east. At the same time, the area was threatened by a Confederate invasion from Texas. The army abandoned and burned Fort Breckinridge in July, 1861, as well as other posts in southern Arizona to keep them from falling into possession of the Confederacy.[6]

In May, 1862 the site of the fort was reoccupied for the U.S. forces, by California volunteer infantry. They rebuilt the fort and renamed it Camp Stanford for Governor Leland Stanford of California. By late 1862 the fort was again also being referred to as Fort Breckenredge, but this time spelled with the "i" changed to an "e". The change in spelling reflected disillusion with the former Vice President, for whom the fort was originally named, since after the Civil War started he "went south" and became a Confederate general.

Use from 1865 to 1872

After the Civil War was over, in November 1865 the post was re-constructed yet again by five companies of the 2nd Regiment California Volunteer Infantry commanded by Colonel Thomas F. Wright.[2] The post was again sited in the San Pedro valley near the confluence of Aravaipa Creek, but in this reconstruction the site of the post was farther south than the earlier sites, and closer to the San Pedro River.[1] Initially the construction site was referred to as Camp Wright,[1] or as the Camp on San Pedro, but after construction the post was officially named Camp Grant to honor the Union general Ulysses S. Grant.[1] The post was also officially downgraded from a fort to a camp, though it continued to be commonly referred to as both Fort Grant and Camp Grant.[1]

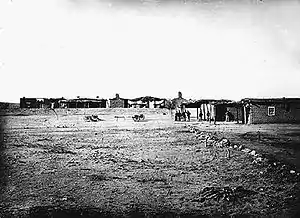

In March 1866 regular troops of the 14th Infantry[2] relieved the 2nd California Volunteers.[6] In the summer of 1866 rains caused the San Pedro to flood and Camp Grant was so damaged that the troops then rebuilt the post on a higher terrace on the east bank of the San Pedro River, just north of the confluence with Aravaipa Creek.[11] The site after relocation was closer to the original sites of the earlier Fort Breckinridge and Camp Stanford,[1] and is the site pictured in the photo above.

Host to Aravaipa and Pinal Apache

Over successive years the Army's persistent pursuit of raiding Apache parties caused accrual of casualties among the raiders. As these casualties mounted, the hostile Apache bands could not replace their losses. The hostile Apache bands were slowly worn down by attrition.

In 1870 some Apache bands had indicated a willingness to give up raiding and adopt a sedentary life style in return for rations. Army and civilian authorities began discussing various sites for reservations for Apache bands scattered throughout the Arizona and New Mexico territories.[12] In 1870 Col. Stoneman was in command of the Army in the Arizona Territory. He articulated a peace policy advocating "feeding stations" which would provide rations to the Apache. It was hoped this policy would lead to abandonment of raiding by Apache bands. acceptance of placement on reservations, and consequently a reduction of depredations across the territory.[13]

In February 1871 five old Apache women, hungry and poorly clothed, came to Camp Grant to look for a son of one of the women who had been taken prisoner. Lt. Royal Emerson Whitman, newly arrived from the east, was the senior commander of the three troops of Third Cavalry at Camp Grant. He fed the five women, treated them kindly, and sent them off with a promise to similarly treat others who would come into Camp Grant.[13] Word spread and other Apaches from Aravaipa and Pinal bands soon came to the post seeking rations of beef and flour. Among them was a young Apache war chief named Eskiminzin who told Lt. Whitman he and his small band were tired of war and wanted to settle on Aravaipa Creek.[13] In return for rations, Lt. Whitman disarmed the Apaches. offered them pay for work (gathering hay), and extracted a promise to cease raiding. As more Apache arrived, Whitman created a refuge (or "rancheria") along Aravaipa Creek about .5 miles east of Camp Grant, and wrote to Col. Stoneman (who was then in California) for instructions. Due to a bureaucratic mixup, Stoneman made no reply. By early March there were 300 Aravaipa and Pinal Apache camped near Camp Grant, and by the end of March there were 500. During March the flow of Aravaipa Creek declined and Lt. Whitman authorized the Apache to move five miles upstream, away from Camp Grant, to the mouth of Aravaipa canyon.[13]

Camp Grant Massacre

Before 1871, there was considerable tension between Tucson and the residents of Camp Grant. Camp Grant guarded the San Pedro River overland freight road that ran from New Mexico to California, and the San Pedro route was in competition with an alternative overland route that went through Tucson. In addition, Tucson residents viewed themselves as surrounded by a vast land area in which deadly Apache raiding parties operated freely, with little or no effective check by soldiers from Camp Grant or other Arizona posts. Ironically, supplying Army posts and garrisons in Arizona involved many Tucson businessmen, and the feeding program being tried out at Camp Grant could potentially lead to the pacification of the Apache, the reduction of the Army garrisons and the suppression of this lucrative business.

As Pinal and Avavaipa Apache collected at Camp Grant in early 1871, raids continued in Arizona—19 settlers had been killed and 10 wounded between March 7 and 29.[13] Though some raids occurred long distances away from Camp Grant allegations by Tucson residents attributed these raids to the swiftly growing base of 500 Apache at Camp Grant.[13] Camp Grant was located about 50 miles (80 km) northeast of Tucson, and Anglo-Hispanic citizens from Tucson reacted angrily and fearfully to this unprecedented concentration of Apaches. Excited mass meetings were held and radical solutions suggested.[13]

On the morning of April 28, 1871 a group of 6 Americans and 48 Mexicans left Tucson for Camp Grant, along with 94 Tohono O'odham (aka Papago) Indians.[13] The Papago Indians had been recruited by Tucson residents from their reservation to the south. The Papago were traditional enemies of the Pinal/Aravaipa Apache based on a long history of inter-tribal warfare, with ingrained and deep seated hatreds.

At dawn on April 30, 1871 the Tucson group attacked the camps of the Pinal and Aravaipa Apaches. The camps were not expecting any attack, having surrendered their weapons and promised to give up raiding. The men of the camp were off in the mountains hunting. The Papago Indians were at the forefront of the attack. Two look-outs were killed with clubs, after which a skirmish line swiftly advanced on the camp clubbing and knifing victims. Those escaping the skirmish line were shot. An estimated 110 to 144 Apache people were killed. Since the male members of the Apache groups were off hunting, all but 8 of the victims were women and children. Chief Eskiminzin was present but escaped. 27 to 30 Apache children were captured by the Papagos and taken back to be slaves or servants.[13] In the years following the massacre, though the children's relatives constantly petitioned the U.S. to intervene and have the children returned, only 7 or 8 were ever repatriated.

Lt. Royal Emerson Whitman, Camp Grant commander, had belatedly learned of the expedition from Tucson and sent a warning message to the Indian camp, which arrived too late. He then sent a medical team to render assistance, but no survivors were found. He reported that the dead totaled 125,[13] which he buried. This event became known as the Camp Grant Massacre. News spread and caused consternation among Apaches, increasing their distrust of dealings with non-Indians. The "massacre" caused an outraged reaction from eastern newspapers. President Grant threatened to place the territory under martial law if the participants were not brought to trial. A grand jury indicted about 100 persons in October 1871. Following a five-day trial all were acquitted after the jury deliberated 19 minutes.[13] At the trial, the defense of those accused focused exclusively on the history of Apache raids, killings and depredations in the years preceding the event.

Site abandoned

The massacre had repercussions for Camp Grant and for the Arizona Territory. Colonel Stoneman, the commanding officer in the Arizona Territory, was replaced by Lt. Col. George Crook in May 1871.[13] Though historians believe that the decision to replace Col. Stoneman was made prior to the massacre, the massacre probably influenced Col. Crook. He undertook a survey of military posts and potential reservations sites throughout the Arizona Territory, and attention naturally focused on Camp Grant. In 1872 Col. Crook ordered that a new Fort Grant be established at the base of Mount Graham, and that "old" Camp Grant be closed. The move had strategic benefits. New Fort Grant (in present day Graham County) was better located to fight those bands of Apache who were still hostile. The move had other benefits. Malaria at the "old" Camp Grant along the San Pedro River had been a continual problem.[11] In March 1873, the site of "old" Camp Grant at the junction of the San Pedro and Aravaipa was finally abandoned .[6]

The site of "old" Camp Grant at the junction of Aravaipa Creek and the San Pedro River is near the current location of the Aravaipa campus of the Central Arizona College. The "new" Fort Grant under Mount Graham is no longer an army post, but has been integrated into the Arizona State Prison system, administered from Safford, Arizona.

After the massacre in 1871 a Camp Grant reservation was set aside for the Apache, but in 1872 as part of a new policy to consolidate Apache reservations, the temporary Indian Reservation near Camp Grant was moved to a reservation newly established at the junction of the San Carlos and the Gila River. The massacre site is unmarked[14] and is only known to have occurred in an area five miles upstream from Camp Grant on Aravaipa Creek.

Current location

The location of the site of the fort is slightly east of the current Junction of Highway 77 and East Putnam Street, north of where Highway 77 crosses Aravaipa Creek.[15] Very little remains of the former fort and camp.[6][11] The barren site is on privately owned land and is covered with mesquite and cactus and a scattering of rubble and ruins.[16]

See also

References

- "Arizona Forts". Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- "Old Fort Grant". "Alan's Kitchen". Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- See Wikipedia Article:2nd Regiment California Volunteer Infantry

- Hastings, James R. (Summer 1959). "The Tragedy at Camp Grant in 1871". Arizona and the West. Vol 1 (No 2): 146–160. JSTOR 40166938.

- Worcester, Donald Emmet (1979). The Apaches: Eagles of the Southwest. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. Chapter II, III, IV, p. 25 to 81. ISBN 978-0-8061-2397-4. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- legends. "ARIZONA LEGENDS Fort Breckinridge". Legends of America. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "The Cactus Files, a timeline of historical events". Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "Blazing Trails: Discovering Routes through Arizona to California" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "FORT BRECKINRIDGE (Old Camp Grant)". National Park Service. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "Fort Breckinridge attacked". The Civil War Sesquicentennial Day by Day. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project CAMP GRANT, with Map of location of Camp Grant, and location of Graveyard". Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Victorio and the Mimbres Apache. Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-1645-7.

- Fordney, Ben Fuller (2008). George Stoneman: a biography of the Union general. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-7864-3225-7. pp. 149-155

- "Old Camp Grant". Treasure Net. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "Camp Grant". Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project – This site has maps of the old camp coordinated with modern maps. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "FORT BRECKINRIDGE (Old Camp Grant)". National Park Service. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

External links

- PBS, The West, Photograph of Camp Grant

- Arizona Pioneer & Cemetery Research Project CAMP GRANT, with Map of location of Camp Grant, and location of post graveyard, and orientation of photo depicted above

- The 'Camp Grant Massacre' in the Historical Imagination, Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, Arizona History Convention Tempe, Arizona, April 25 – 26, 2003

- Western Apache Oral Histories and Traditions of the Camp Grant Massacre, Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Chip, American Indian Quarterly, Summer & Fall 2003, Vol. 27, nos. 3 & 4, photo of massacre site at 640, map showing relation of Camp Grant and site at p. 641

- Eskiminzin, Aravaipa Apache chief