Canonbury Tower

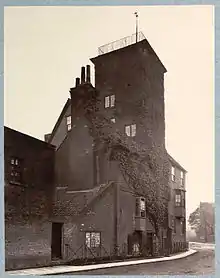

Canonbury Tower is a Tudor tower in Canonbury, and is the oldest building in Islington, North London. It is the most substantial remaining part of what used to be Canonbury House, erected for the Canons of St Bartholomew's Priory between 1509 and 1532. The tower has been occupied by many historical figures, including Sir Francis Bacon and Oliver Goldsmith. It is a Grade II* listed building,[1] and is located in Canonbury Place, 100 metres (330 ft) east of Canonbury Square.

| Canonbury Tower | |

|---|---|

Canonbury Tower, viewed from the northwest | |

| Location | Islington, London, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51.54429°N 0.098611°W |

| Height | 66 feet (20 m) |

| Built | Between 1509 and 1532 |

| Built for | Prior and Canons of St Bartholomew's |

| Restored | 1907–08 |

| Restored by | 5th Marquess of Northampton |

| Current use | Masonic research centre |

| Architectural style(s) | Tudor |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

Location within Islington | |

History

Before the Norman Conquest the land now contained in the triangle formed by Upper Street, Essex Road and St Paul's Road was an Anglo-Saxon manor. Passing to Norman ownership, it finally became part of the vast estates of the de Berners family.[2] In 1253 Ralph de Berners made a grant of "lands, rents and their appurtenances in Iseldone" to the Prior and Canons of St Bartholomew's – an Augustinian order – in Smithfield. The area thus became known as the Canons' Burgh.[3]

In 1509 William Bolton was elected as the new Prior. Bolton substantially restored and added to St Bartholomew's and was Henry VIII's Master of the Works for the building of the Henry VII Chapel in Westminster Abbey. He also built a mansion in Canonbury for himself, his Canons and his successors.[4] It is uncertain how much of the Canonbury House that took shape in the 16th century was Prior Bolton's work, but the tower is certainly his work; some sources give the date for the tower as c. 1562, but this is incorrect as Prior Bolton died in 1532.

When the monasteries were dissolved by Henry VIII, St Bartholomew's and its appendages were among the last to be taken. Prior Robert Fuller surrendered the Priory and its lands to the Crown on 25 October 1539. Henry VIII bestowed the manor of Canonbury on his Chief Minister for the Dissolution, Thomas Cromwell,[5] only a year before his execution on 28 July 1540.

In 1547 the manor was granted by Edward VI to John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, later Duke of Northumberland. He was executed in 1553 for his abortive attempt to place his daughter-in-law, Lady Jane Grey, on the throne. Queen Mary I in 1556 granted the manor to one David Broke, and in 1557 to the second Lord Wentworth.

John Spencer first leased the house from Wentworth for £21.11s.4d, and then bought it for £2,000. Spencer was popularly known as "Rich Spencer"[6] and he amassed one of the greatest private fortunes of his day. He rose to become Sir John Spencer, Knight, Lord Mayor of London in 1594. Spencer took up regular occupation of Canonbury House in 1599, and modernised the tower to make it inhabitable and added the main embellishments such as plaster ceilings, panelling and ornamental mantelpieces, which all date from that period. Thereafter it often becomes hard to determine whether individuals were resident in the house or in the tower. In 1605 the Lord Chancellor, Thomas Egerton, later Earl of Ellesmere, issued some Charters from Canonbury House and was presumably in residence.

Spencer had no son but a daughter Elizabeth. She had fallen in love with William Compton, 2nd Baron Compton, who succeeded his father in 1589 when only 21 and went to the royal court of Queen Elizabeth I, borrowing from John Spencer[7] when he had spent what his father had left him. Spencer did not regard marriage to his daughter as a suitable way of liquidating the debt, so he opposed it and confined his daughter in Canonbury Tower.[8] She and Lord Compton eloped: supposedly, the young lord disguised as a baker's boy drove his cart over the fields to Islington and Elizabeth was lowered from a window in a baker's basket and escaped to marriage in 1599.[9] Sir John disowned his daughter, costing the couple a fortune variously estimated at from three hundred to eight hundred thousand pounds. However, a son was born to the Comptons in 1601, and Spencer was partially reconciled through the efforts of the Queen, saying that having now no daughter he would adopt the child as his son. The reconciliation was completed with the birth of a second child, a daughter, in Canonbury House[10] and the fortune found its way to them on Spencer's death in 1610. Compton then became "in great danger to loose his witts" and spent "within lesses than eight weekes...£72,000, most in great horses, rich saddles and playe",[11] and on gambling, entertaining and extending the country seat at Castle Ashby, Northamptonshire, and not on Canonbury House which was let. The young lord eventually became Lord President of the Council in 1617, and in 1618 was created 1st Earl of Northampton.

From 1616 to 1625 the house was leased to Sir Francis Bacon, philosopher and statesman, who was at first Attorney General and the year after Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. There is a tradition that Bacon planted the mulberry tree that still flourishes in the courtyard next to the tower to encourage the home production of silk.

In the English Civil War, Spencer Compton, 2nd Earl of Northampton and his six sons supported the King's cause. The Earl was killed at the Battle of Hopton Heath. The family was fined £40,000 during the Commonwealth, sold property and mortgaged Canonbury House, where they took up residence. The mortgage dated 1661 included "all that capital messuage and Mansion House commonly called Canonbury alias Canbury House, and all that tenement called the Turret House situated and being at the end of the courtyard and the Park, to secure £1751". A son was born to James Compton, 3rd Earl of Northampton at Canonbury House in 1653 and another died aged five in 1662. No other Earl or Marquess of Northampton has since resided at Canonbury House.

During the 18th century the buildings were let, part of them in separate rooms.[12] At Christmas 1762 the novelist, playwright and poet Oliver Goldsmith took a room in the house which he occupied for about eighteen months, allegedly often using it to hide from his creditors. It is uncertain whether any of his novel The Vicar of Wakefield was written in Canonbury Tower, where tradition has it that Goldsmith occupied the Spencer Room. On Sunday, 26 June 1763 James Boswell notes in his London Journal: "I then walked out to Islington to Canonbury House, a curious old monastic building now let out in lodgings where Dr. Goldsmith stays. I took tea with him and found him very chatty."[13]

An earlier literary lodger was Samuel Humphreys whose libretti for three of Handel's early oratorios – Esther, Athalia and Deborah – date from 1730 to 1738, when he died. Handel "esteemed the harmony of his numbers".[14]

The publisher John Newbery was in residence between 1761 to 1767. Newbery wrote numerous books for the young with such titles as "Logic made familiar and easy". His best known creation was Goody Two-Shoes.

Ephraim Chambers, the first cyclopaedist, died there in 1740. He was unrelated to his namesakes who founded Chambers's Encyclopaedia.

Another lodger was the printer and journalist Henry Sampson Woodfall, who edited the Public Advertiser in which from 1769 for three years the Letters of Junius appeared, to the great discomfiture of the government. Woodfall was tried for printing the letters and accused of seditious libel, but went free after the judge decided in favour of a mistrial. His grandfather Henry Woodfall invented the characters Darby and Joan.

In 1767 Mr John Dawes, a City stockbroker, acquired a lease of the whole house and adjoining grounds. He added bay windows to the tower and in a significant change he demolished the entire south range of the old Canonbury House and on its site built the houses now numbered 1–5 Canonbury Place overlooking the garden.

At some unspecified date, probably in the 1790s, a handsome small mansion for which no records survive was built adjoining the tower, partly filling the west side of the old manor house court. This building has also confusingly come to be known as Canonbury House.[15]

In the early nineteenth century Washington Irving, creator of Rip Van Winkle, hoped to be inspired by Goldsmith's muse and engaged his room – reputedly the Spencer Room – at the tower, which he referred to as "Canonbury Castle". He remained only a few days. When Sunday came he was "stunned with shouts and noises from the cricket ground" nearby and his "intolerable landlady" was perpetually bringing parties of visitors not only up to the tower but into the room where he was working. He remonstrated, locked the door and pocketed the key, only to hear the landlady allowing the visitors to peep through the keyhole at the "author who was always in a tantrum when interrupted".[16]

.jpg.webp)

Charles Lamb, essayist, poet, and antiquarian, loved to visit the tower when he lived in Islington. He was "never weary of toiling up the steep winding stairs and peeping into its sly comers and cupboards".[17] He also enjoyed the view from the top.[18] A book written in 1835 still speaks of its being possible to see from there "the adjacent villages and surrounding countryside".

From 1826 to 1907 the tower was the home of the bailiff of the estate. In 1885 it is described as being in a sadly dilapidated state. "Although the exterior looks substantial enough, and the splendid carved wood panelling is intact, all the rooms are deserted and many are decaying".[19]

In 1907 an American advocate of the Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship travelled to England. She believed she had decoded a message which revealed that Francis Bacon's secret manuscripts were hidden behind panels in the tower.[20][21] None were found.

In 1907–08 the 5th Marquess of Northampton completely restored the tower, preserving the original features where rebuilding was necessary. The ivy was removed: before removal, one main trunk of ivy was 9 inches (0.23 m) thick and the growth had made holes 3 feet (0.91 m) square in the brickwork. The iron railings round the top of the tower were replaced by a brick parapet; and some of the old oak roof beams were used for restoration. A new building was erected adjacent to the tower, King Edward's Hall; it served as a recreation hall and with the tower itself formed the premises of a social club for the residents of the Marquess's Canonbury and Clerkenwell estates.

In 1924 the Francis Bacon Society was granted a tenancy of part of the gabled building east of the tower, and made its headquarters there with its remarkable library.

Early in 1940, when many of the estate tenants had been evacuated and a large proportion of the houses were standing empty, the social club surrendered its tenancy. Shortly afterwards, for fear of damage by enemy action, the sixteenth-century oak panelling and chimney pieces in the Compton and Spencer Rooms were taken down section by section for storage at Castle Ashby until the war ended. The damage caused by bombing to the historic buildings in Canonbury was negligible. From 1941 onward, Canonbury Tower and King Edward's Hall were used as a youth centre for the benefit of some 300 boys and girls, most of whom were living on the estate. After the war, the youth centre was rehoused elsewhere on the estate. The panelling and chimney pieces were brought back, cleaned and restored under the supervision of the Keeper of Woodwork at the Victoria and Albert Museum, and reinstated. The Marquess provided suitable furniture for the Compton and Spencer Rooms and the great brass chandeliers which now light those rooms.

In 1952, the Tavistock Repertory Company took a lease of the tower and King Edward's Hall. As the Tower Theatre Company it mounted nearly 1600 productions in the hall, ending when the lease expired in 2003.

Since 1998 the tower has been used as a Masonic research centre.[22] It can occasionally be visited as part of a guided tour.

Description

The tower is 66 feet (20 m) high and about 17 feet (5.2 m) square. The brick walls vary in thickness from 4 feet (1.2 m) to 2 feet 6 inches (0.76 m). The main entrance hall leads into a low hall adjoining the tower itself, and on the ground floor is a room with the original brickwork exposed.

Spencer Room

The room on the first floor commemorating the occupancy and work of Sir John Spencer is the plainer of the two panelled rooms. The chimneypiece is the most elaborate part, with lions' heads. At the top just below the ceiling there are three curious carved figures like the figurehead of a ship and there is another, which has lost its head, at eye level in the centre, just below a pair of bellows. There is strapwork ornament on the underside of the mantelpiece, and at either side Tudor roses in what might be garters prefigure or reflect the Rosicrucian interests of Sir Francis Bacon.[23] The same pattern is found on the upright pillars of the Great Bed of Ware. Twelve flat pilasters run from floor to ceiling.

By the end of the 16th century the Italian workmen who had come over to help Henry VIII on his various projects – the tomb of Henry VII and Greenwich and Whitehall Palaces – had mostly gone back and the workmanship is probably mainly Flemish.

Compton Room

On the second floor the panelling is more elaborate, of the type called "panel within panel", and there is liberal use of strapwork on the ten pilasters. The chimneypiece again is elaborate, with figures of Faith (one knee exposed, one arm missing) and Hope in a border of flowers and abstract pattern. The Latin inscribed beneath Faith – Fides Via Deus Meta – means "Faith is my way, God is my aim", and under Hope – Spes Certa Supra – means "My sure hope is above". The frieze over the fireplace consists of pomegranates and exotic fruits. Elsewhere it is a shell pattern, with at various intervals the arms of Spencer (argent two bars gemelle between three eagles displayed sable) and semi-grotesque heads. On the east side the panelling has been moved forward to provide another room, which contains bricked up a mullion window of the original type – replaced by windows of seasoned Oregon pine elsewhere in these rooms. The room is now all that remains of the occupancy of the Francis Bacon Society. Over the main door there is a carving known as a "cresting" incorporating a spread eagle.

Staircase

The tower, whose core is the central staircase, has a stairway in short straight flights and quarter landings, with the centre filled in with timber and plaster forming a series of cupboards. The black oak of the balusters is mostly original timber. At the top, the handrail newel and baluster are cut from sound oak beams found among the woodwork during the restoration of 1907–08: four centuries old but when sawn still fresh and sweet smelling.

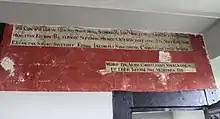

Inscription Room

The space below the roof forms a small room, once presumably a schoolroom, containing a list of the Kings and Queens of England, from Will Conq to Carolus qui longo tempore in rough Latin and Norman French hexameters. There is also a mnemonic in Latin elegiac which can be translated as "Let your thoughts be on your own death, the deceits of the world, the glory of heaven and the pains of hell". On the roof itself, which was not originally flat, is a weather vane said to be copper. The iron railings originally there are now at ground level at the front of the building.

In literature

Charles Dickens wrote a Christmas story about a lamplighter in Canonbury, which features Canonbury Tower.[24]

Nearest stations

References

- "Listing for Canonbury Tower". List of Protected Historic Sites. Historic England. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Baggs, A. P.; Bolton, Diane K.; Croot, Patricia E. C. (1985). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 8, Islington and Stoke Newington Parishes. London: Victoria County History. pp. 51–57. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Fincham, Henry. W. (1912). "An Historical account of Canonbury Tower". Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 18 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1080/00681288.1912.11893802. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- Stow, John (2005). A survey of London : written in the year 1598. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750942401. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Brewer, J. S. "Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 5, 1531-1532". British History Online. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Thornbury, Walter (1878). Old and New London: Volume 2. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin. pp. 269–273. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Chamberlain, John (1939). The Letters of John Chamberlain, vol. 1. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Recognisances for Debt, 192. Public Record Office.

- Willats, Eric A. (1987). Streets with a Story: Islington (PDF). London: Islington Local History Education Trust. p. 40. ISBN 0-9511871-04. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- St. Mary's Islington Parish Register.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. London: Sidgwick and Jackson Limited. p. 91. ISBN 0-283-97937-2.

- Lysons, Daniel (1795). The Environs of London: Volume 3, County of Middlesex. London: T Cadell and W Davies. pp. 123–169. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- Boswell, James. London Journal 1762-1763. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "The Daily Post". 1738. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Cosh, Mary (1993). The Squares of Islington: Part II. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. p. 37. ISBN 0-9507532-6-2.

- Irving, Washington (1824). Tales of a Traveller, by Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Daniel, George (1863). Love's Last Labour Not Lost. London: B. M. Pickering. p. 14. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. London: Sidgwick and Jackson Limited. p. 111. ISBN 0-283-97937-2.

- Welsh, Charles (1885). A Bookseller of the Last Century. London: Griffith, Farren, Okeden & Welsh. p. 48. ISBN 978-0469561311. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Shapiro, James (2010). Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare?. US edition: Simon & Schuster. p. 144 (127). ISBN 978-1-4165-4162-2. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Wadsworth, Frank W. (1958). The Poacher from Stratford: A Partial Account of the Controversy Over the Authorship of Shakespeare's Plays. University of California Press. p. 64.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "History of Canonbury Tower". Canonbury Masonic Research Centre. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Yates, Frances A. (2002). The Rosicrucian enlightenment (2 ed.). London: Routledge. p. Chapter IX. ISBN 0415267692.

- The Lamplighter Charles Dickens (Public Domain) accessed 29 September 2009

Sources

- Cosh, Mary (1993). The Squares of Islington: Part II. London: Islington Archaeology & History Society. ISBN 0-9507532-6-2.

- Cosh, Mary (2005). A History of Islington. London: Historical Publications Ltd. ISBN 0-948667-97-4.

- Oakley, Richard (1980). Canonbury Tower: a Brief Guide. London: Tavistock Repertory Company.

- Willats, Eric A. (1986). Islington: Streets with a Story. London: Islington Local History Education Trust. ISBN 0-9511871-04.

- Zwart, Pieter (1973). Islington: A History and Guide. London: Sidgwick and Jackson Limited. ISBN 0-283-97937-2.

External links

Bibliography

- Nichols, John (1788). The History and Antiquities of Canonbury-House, at Islington, in the County of Middlesex. ISBN 978-1379988045.

- Nelson, John (1811). The History, Topography, and Antiquities of the Parish of St. Mary Islington, in the County of Middlesex. ISBN 978-1241600754.

- Lewis, Samuel (1842). The History and Topography of the Parish of Saint Mary, Islington, in the County of Middlesex. ISBN 978-1173880927.

- Tomlins, Thomas Edlyne (1858). Yseldon. A Perambulation of Islington. London: James S. Hodson; K. J. Ford. ISBN 978-1153222815.

- Calendar of State Papers.

- Northampton Family Documents.

- Chamberlain, John (1861). Correspondence. Camden Society.

- Parish Registers.

- Dictionary of National Biography.

- Marquess of Northampton (1926). Article in Country Life.

- Guide to Great St. Bartholomew's Church.