Capacocha

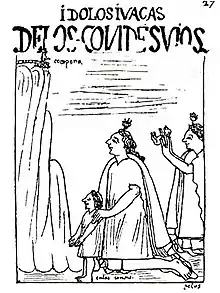

Capacocha or Qhapaq hucha[1] (Quechua qhapaq noble, solemn, principal, mighty, royal, hucha crime, sin, guilt[2][3] Hispanicized spellings Capac cocha, Capaccocha, Capacocha, also qhapaq ucha) was an important sacrificial rite among the Inca that typically involved the sacrifice of children.[4] Children of both genders were selected from across the Inca empire for sacrifice in capacocha ceremonies,[5] which were performed at important shrines distributed across the empire, known as "huacas", or "wak'as".

Capacocha ceremonies took place under several circumstances. Some could be undertaken as the result of key events in the life of the Sapa Inca, the Inca Emperor, such as his ascension to the throne, an illness, his death, the birth of a son.[6] At other times, Capacocha ceremonies were undertaken to stop natural disasters performed as major festivals or processions at important ceremonial sites.[6] The rationale for this type of sacrificial rite has typically been understood as the Inca trying to ensure that humanity's best were sent to join their deities.[5]

The children chosen for sacrifice in a capacocha ceremony were typically given alcohol and coca leaves[7] and deposited at the place of the ceremony. Sacrifice was primarily carried out through four methods: strangulation, a blow to the head, suffocation, or being buried alive while unconscious,[6] though if the ceremony was carried out in a particularly cold place, they could die from hypothermia.[8] Some Spanish records tell of Incas removing victims' hearts, but no evidence of this has been found in the archaeological record; it seems more likely that this practice was witnessed by the Spaniards among the Aztecs and wrongly attributed to the Incas as well.[6]

Ceremony

Selection of children

Children selected for sacrifice in capacocha ceremonies were of both genders. No region was exempt from the recruitment of these child sacrifices; they could come from any region of the empire.[5] The male victims were no older than ten and girls could be up to age sixteen but must be a virgin when chosen; they had to be perfect, unblemished by even a freckle or scar.[9]

While the boys were immediately brought to Cuzco, the young girls, called aclla, taken for sacrifice were often entrusted to the mama-kuna, in the "House of Chosen Women" (aqlla wasi).[10] Chosen for their looks, the girls were taught to weave and sew here for an extended time. The mama-kuna women were compared to nuns by many Spanish men, as they lived celibate lives, serving the Gods.[10] There were three groups the girls were divided into. Some girls never left and went on to raise the girls brought after them, and the prettiest were sent as tribute.[10] The rest from the girls brought to become Chosen Women became slaves and concubines in Cuzco, for the noblemen.[10]

Capacocha at Cuzco

The capacocha sacrifice started at the capital city of Cuzco, on the order of the Sapa Inca. The first Sapa Inca to do this sacrifice was Pacha Kuti.[11][10] During the festivities of the Capacocha in Cuzco, it was decided what type and quantity of offerings each shrine or wak'a would receive, of which the Incas maintained a clear record. The tributes were fed well, and those too young to eat would have their mothers with them to breastfeed.[9] This was to ensure that they would be well fed and happy when they prepared to reach the gods.[9] The children were paired off, girl and boy, and dressed finely like little royals.[5] They were paraded around four large statues, of the Creator, the Sun God, the Moon God, and the Thunder God.[5] The Sapa Inca would say to the priests then to divide the children, along with the other sacrifices, in four, for each of the four suyu regions.[5] He would then order the priests to make their sacrifices at their main wak'as.[5]

Sacrifice at the wak'as

After the ceremonies at Cusco, the children, the priests and their entourage of companions undertook the trip back to their communities. When they returned, they did not follow the royal road, or the Inca road, as they had gone, but they had to follow a path in a straight line, possibly following the ceque lines that left Cusco and went to the wakas. This was a long and tedious journey, crossing valleys, rivers and mountains, which could take months.[12]

Once at the summit the young victims would then be administered an intoxicating drink or other substance to either induce sleep or a stupor, ostensibly to let the final ritual go on smoothly.[7] If the ceremony was carried out in a particularly cold place, they could die from hypothermia,[8] in other cases death was provoked in a more violent manner, such is the case of the Aconcagua child, with a strong blow to the head,[13] as well as that of the girl at Sara Sara and the young woman from the snowy Ampato,[14] while the cause of death of the "Queen of the Hill" was a puncture wound in the right hemithorax, which entered through her back.[15] While in some cases, as in Llullaillaco, the bodies were deposited in a burial chamber and covered with gravel,[16] or, in the case of Cerro El Plomo, the sacrificial victim was wrapped in a complex funerary bundle of several pieces with a specific function and message,[17] as in the case of Aconcagua.[18]

When the sacrifices of children and material offerings were buried, the holes couldn't be made using any metal, but in the ceremony dug out using sharpened sticks.[9] Once dead, the children would then be buried in a fetal position, wrapped up in a bundle with various artifacts within the bundle or next to it in the same grave.

Non-human sacrifice and offerings

A number of offerings were often left with the sacrificed individuals at the sites of capacocha ceremonies. The human body itself was often finely dressed and clothed in a feathered headdress and other ornamentation such as a necklace or bracelet.[19] The most elaborate artifacts were typically paired human statuettes and llama figurines that have been crafted with gold, silver, and spondylus shells.[5] The combination of both male and female figurines alongside the use of both gold and silver was likely meant to pay tribute to the male Sun and the female Moon.[5] Several sets of ceramics as well as gold, silver, and bronze pins were relatively commonplace too.[4] A large amount of cloth was a typical find at capacocha sites too.[4] Some objects that often appear such as plates and bowls have often been found in pairs.[19] Alongside these objects are sometimes found food items.[19] All objects, animals, and people sacrificed to a wak'a, not only represented Inca symbols but were also previously legitimized in ceremonies conducted by the emperor himself.[20]

Historical accounts

The fullest description of a capacocha comes from Cristobal de Molina[5] who placed it in the context of a monarch’s ascension. He wrote that all of the towns of the empire were called upon to send one or two boys and girls about 10 years old to the capital, along with fine cloth, camelids, and figurines of gold, silver, and shell. The boys and girls were dressed in finery and matched up as if they were married couples.[5] Priests were then dispatched to the four quarters with sacrificial items and orders to make offerings to all wak’a according to their rank. The parties left the city in straight-line paths, deviating for neither mountain nor ravine. At some point, the burdens were transferred to other porters, who continued along the route. The children who could walk would do so, while those who could not were carried by their mothers. The Inca himself traveled the royal road, as did the flocks.[5]

Archaeologically, the evidence to support sacrifices at that scale is lacking.[5] Bauer, In his fieldwork among the wak’as of Cuzco, found surface evidence of human burial at three shrines, but nothing approaching the thousands of victims described in the chronicles has yet been reported.[5] Even so, Molina’s comment that the rituals paid special attention to high peaks has been supported by the archaeological finds described.[5] The principal offerings recovered from those sites – gold, silver, spondylus shell, and children – also nicely match the priest’s account.[5]

Cultural Significance

In Inca culture, the dead served as link between the Inca people and the gods.[21] Capacocha served as way to appease the gods, who otherwise might cause natural disasters like floods, earthquakes, and famines as a punishment for the people's sins.[22] Children sacrificed in capacocha ceremonies became servants of the gods,[5] or, in capacocha ceremonies following an emperor's death, servants to the emperor.[22] They also served as guardians of the areas where they were sacrificed.[23]

Children sacrificed in capacocha ceremonies were also commemorated by their home communities, or ayllus.[24] Having a child sacrificed in a capacocha ceremony was also considered a great honor to the family, and parents sometimes volunteered their children for sacrifice.[25]

High-altitude sites

Special attention was paid by the Inca to a number of ceremonial wak'a sites at very high elevations.[5] Over 100 ceremonial centers and shrines were built within Inca territories on or near the high summits of the Andes Mountains.[19] These sites were often meant to function both religiously and politically. Some mountains were viewed as origin places or the home to important mountain deities.[5] Building shrines on these mountains both paid homage to the deities and also placed an imperial stamp on areas important to local beliefs, fulfilling both religious and political goals.[5][19] In a number of instances, typically at the most important of these mountains, these sites contain the mummified remains of children sacrificed in capacocha ceremonies.[5][19] Capacocha ceremonies at these important locations held a great deal of weight. Inca priests would periodically visit wak'a distributed across the Inca realm and certificate if they still maintained its power or had lost it, on occasions destroying the discredited wak'a.[26]

Travel to these sites would have involved a procession of priests, the children who would be sacrificed, and a number of other important individuals throughout the empire.[6] Different peoples would assist with the procession as the group moved throughout the different regions of the empire.[6] These sites were difficult to reach and even more difficult to work on. In order to increase the ease with which these mountaintop locations could be reached, the Incas built staging stations lower on the mountains and also made paths that lead up to the summit.[5] Some preparation would likely have occurred at tambos situated nearby.[6]

Llullaillaco

One particularly noteworthy site was found near the summit of Mount Llullaillaco, a volcano in Argentina that lies near the Chilean border.[27] This mountain appears to have been the site of the conclusion of a capacocha ceremony, taking place at an elevation of around 6,739 meters above sea level.[6] In 1999, the mummies of three relatively young individuals were found at the top of the mountain alongside a diverse assemblage of artifacts.[4] Excavations around the main ceremonial structure, a rectangular platform, revealed the burials of a young woman of about 14 years of age, a girl of about 6 years of age, and a boy of about 7 years of age along with over 100 offerings of various materials.[19][4] Due to the frigid conditions, both the mummies and the materials were incredibly well preserved.[19] Some of the notable artifacts found at the site include a feathered headdress, well-made clothing, a number of ceramics, bowls and spoons made of wood, various food items, figurines made out of gold, silver, and spondylus, and other metal objects such as pins.[19]

Due to the incredible preservation of the children, a number of studies could be undertaken from their remains. Hair samples indicate that the diets of the children underwent a momentous change in the year before their deaths.[4] This helps to indicate the care with which children were treated during their travels throughout the empire prior to their ultimate sacrifice.[4] Other changes in the isotopes found in the hair samples indicate that the children began their procession to the mountain several months prior to their death.[4] The preservation of both the human remains and the artifacts associated with them has been an invaluable source of information.

See also

- Child sacrifice in pre-Columbian cultures

- List of Andean peaks with known pre-Columbian ascents

Notes

- Of Summits and Sacrifice: An Ethnohistoric Study of Inka Religious Practices, University of Texas Press, 2009

- Teofilo Laime Ajacopa, Diccionario Bilingüe Iskay simipi yuyayk'ancha, La Paz, 2007 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Diccionario Quechua - Español - Quechua, Academía Mayor de la Lengua Quechua, Gobierno Regional Cusco, Cusco 2005 (Quechua-Spanish dictionary)

- Andrushko, Valerie A.; Buzon, Michele R.; Gibaja, Arminda M.; McEwan, Gordon F.; Simonetti, Antonio; Creaser, Robert A. (February 2011). "Investigating a child sacrifice event from the Inca heartland". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 323–333. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.009.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 1-4051-1676-5.

- Reinhard, Johan; Ceruti, Constanza (June 2005). "Sacred Mountains, Ceremonial Sites, and Human Sacrifice Among the Incas". Archaeoastronomy. 19: 1–43.

- Wilson, Andrew S.; Brown, Emma L.; Villa, Chiara; Lynnerup, Niels; Healey, Andrew; Ceruti, Maria Constanza; Reinhard, Johan; Previgliano, Carlos H.; Araoz, Facundo Arias; Diez, Josefina Gonzalez; Taylor, Timothy (2013-08-13). "Archaeological, radiological, and biological evidence offer insight into Inca child sacrifice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (33): 13322–13327. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11013322W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1305117110. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3746857. PMID 23898165.

- MAAM (2010), Guía de referencia de la exposición, Museo de Arqueología de Alta Montaña de Salta

- Cobo, Bernabe (1990). Inca Religion and Customs. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0292738614.

- Besom, Thomas (2009). Of Summits and Sacrifice : An Ethnohistoric Study of Inka Religious Practices. Austin TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292783041.

- Molina, Cristóbal de; Bauer, Brian S.; Smith-Oka, Vania (2011). Account of the Fables and Rites of the Incas. University of Texas Press. pp. 114–120. ISBN 9780292723832.

- de Betanzos, Juan; del Carmen Martin Rubio, Maria (Winter 1990). Murra, John V. (ed.). "Suma y narracion de los Incas". Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 37 (1): 95–97. doi:10.2307/481952. JSTOR 481952.

- Ciner, Patricia Andrea (2010-03-01). "La exégesis del Apocalipsis en el comentario al Evangelio de Juan de Orígenes". Intus-Legere Filosofía (in Spanish). 4 (1): 37–52. doi:10.15691/0718-5448vol4iss1a95. ISSN 0718-5448.

- Johan, Reinhard (1998). Discovering the Inca Ice Maiden: my adventures on Ampato. National Geographic Society. OCLC 607107175.

- "Secretaria de Cultura de Salta Argentina - LA REINA DEL CERRO". 2012-03-10. Archived from the original on 2012-03-10. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- Constanza, Ceruti, María (2003). Llullaillaco: sacrificios y ofrendas en un santuario Inca de alta montaña. Ediciones Universidad Católica de Salta. ISBN 978-9506230142. OCLC 836277798.

- Abal, Clara (2001). Cerro Aconcagua: descripción y estudio del material textil. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo EDIUNC, Mendoza.

- Roberto, Bárcena, J. (2001). Estudios sobre el santuario incaico del Cerro Aconcagua. Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. OCLC 61205067.

- Ceruti, Maria Constanza (March 2004). "Human Bodies as Objects of Dedication at Inca Mountain Shrines (north-western Argentina)". World Archaeology 36 (1): 103*122.

- Duviols, Pierre (1976). La Capacocha. Allpanchis: Revista del Instituto Pastoral Andino, 9.

- Sillar, Bill (1992). The social life of the Andean dead. University of Cambridge. pp. 107–121.

- Ceruti, Maria Constanza (2015). "Frozen Mummies from Andean Mountaintop Shrines: Bioarchaeology and Ethnohistory of Inca Human Sacrifice". BioMed Research International. 2015: 1–12. doi:10.1155/2015/439428. ISSN 2314-6133. PMC 4543117. PMID 26345378.

- Silverblatt, Irene (January 1988). "Imperial Dilemmas, the Politics of Kinship, and Inca Reconstructions of History". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 30 (1): 83–102. doi:10.1017/s001041750001505x. ISSN 0010-4175.

- The Inca and Aztec states, 1400-1800 : anthropology and history. Collier, George A. (George Allen), 1942-, Rosaldo, Renato., Wirth, John D. New York: Academic Press. 1982. ISBN 0-12-181180-8. OCLC 8389637.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Andrushko, Valerie A.; Buzon, Michele R.; Gibaja, Arminda M.; McEwan, Gordon F.; Simonetti, Antonio; Creaser, Robert A. (2011-02-01). "Investigating a child sacrifice event from the Inca heartland". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 323–333. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.009. ISSN 0305-4403.

- Urton, Gary; Hagen, Adriana von (2015-06-04). Encyclopedia of the Incas. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780759123632.

- Grady, Denise (2007-09-11). "In Argentina, a Museum Unveils a Long-Frozen Maiden". The New York Times.

References

- Andrushko, Valerie A.; Buzon, Michele R.; Gibaja, Arminda M.; McEwan, Gordon F.; Simonetti, Antonio; Creaser, Robert A. (February 2011). "Investigating a child sacrifice event from the Inca heartland". Journal of Archaeological Science. 38 (2): 323–333. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.009.

- Besom, Thomas (2009). Of Summits and Sacrifice: An Ethnohistoric Study of Inka Religious Practices. Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292719774.

- Ceruti, Constanza (March 2004). "Human Bodies as Objects of Dedication at Inca Mountain Shrines (north-western Argentina)". World Archaeology. 36 (1): 103–122. doi:10.1080/0043824042000192632. S2CID 161911083.

- Cobo, Bernabe; Hamilton, Roland (2010). Inca Religion and Customs. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292789791.

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2003). The Incas (Reprinted ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 978-1-4051-1676-3.

- Grady, Denise (September 11, 2007). "In Argentina, a Museum Unveils a Long-Frozen Maiden". The New York Times. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- Molina, Cristóbal de; Bauer, Brian S.; Smith-Oka, Vania (2011). Account of the Fables and Rites of the Incas (Reprinted ed.). University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292723832.

- Reinhard, Johan; Ceruti, Constanza (June 2005). "Sacred Mountains, Ceremonial Sites, and Human Sacrifice Among the Incas". Archaeoastronomy. 19: 1–43.