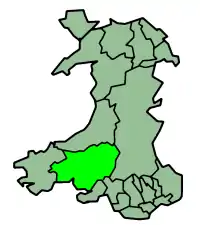

Carmarthenshire

Carmarthenshire (/kərˈmɑːrðənʃər, -ʃɪər/;[1] Welsh: Sir Gaerfyrddin; [siːr gɑːɨrˈvərðɪn] or informally Sir Gâr) is a unitary authority in southwest Wales, and one of the historic counties of Wales. The three largest towns are Llanelli, Carmarthen and Ammanford. Carmarthen is the county town and administrative centre. The county is known as the "Garden of Wales" and is also home to the National Botanic Garden of Wales.

County of Carmarthenshire

Sir Gaerfyrddin | |

|---|---|

unitary authority | |

Guildhall Square and Court House, Carmarthen | |

Coat of arms | |

| |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Wales |

| Preserved county | Dyfed |

| Established | 1 April 1996 |

| County town | Carmarthen |

| Largest town | Llanelli |

| Government | |

| • Type | Carmarthenshire County Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 925 sq mi (2,395 km2) |

| Area rank | Ranked 3rd |

| Population (2017) | |

| • Total | 188,771 |

| • Rank | Ranked 4th |

| • Density | 200/sq mi (79/km2) |

| • Density rank | Ranked 18th |

| • Ethnicity | 98.2% White |

| Welsh language | |

| • Rank | Ranked 3rd |

| • Any skills | 63.6% |

| Geocode | 00NU (ONS) W06000010 (GSS) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-CMN |

Carmarthenshire has been inhabited since prehistoric times. The county town was founded by the Romans, and the region was part of the Principality of Deheubarth in the High Middle Ages. After invasion by the Normans in the 12th and 13th centuries it was subjugated, along with other parts of Wales, by Edward I of England. There was further unrest in the early 15th century, when the Welsh rebelled under Owain Glyndŵr, and during the English Civil War.

Carmarthenshire is mainly an agricultural county, apart from the southeastern part which was once heavily industrialised with coal mining, steel-making and tin-plating. In the north of the county, the woollen industry was very important in the 18th century. The economy depends on agriculture, forestry, fishing and tourism. West Wales was identified in 2014 as the worst-performing region in the United Kingdom along with the South Wales Valleys with the decline in its industrial base, and the low profitability of the livestock sector.[2]

Carmarthenshire, as a tourist destination, offers a wide range of outdoor activities. Much of the coast is fairly flat; it includes the Millennium Coastal Park, which extends for ten miles to the west of Llanelli; the National Wetlands Centre; a championship golf course; and the harbours of Burry Port and Pembrey. The sandy beaches at Llansteffan and Pendine are further west. Carmarthenshire has a number of medieval castles, hillforts and standing stones. The Dylan Thomas Boathouse is at Laugharne.

History

Stone tools found in Coygan Cave, near Laugharne indicate the presence of hominins, probably neanderthals, at least 40,000 years ago,[3] though, as in the rest of the British Isles, continuous habitation by modern humans is not known before the end of the Younger Dryas, around 11,500 years BP.[4] Before the Romans arrived in Britain, the land now forming the county of Carmarthenshire was part of the kingdom of the Demetae who gave their name to the county of Dyfed; it contained one of their chief settlements, Moridunum, now known as Carmarthen.[5] The Romans established two forts in South Wales, one at Caerwent to control the southeast of the country, and one at Carmarthen to control the southwest. The fort at Carmarthen dates from around 75 AD, and there is a Roman amphitheatre nearby, so this probably makes Carmarthen the oldest continually occupied town in Wales.[6]

Carmarthenshire has its early roots in the region formerly known as Ystrad Tywi ("Vale of [the river] Tywi") and part of the Kingdom of Deheubarth during the High Middle Ages, with the court at Dinefwr. After the Normans had subjugated England they tried to subdue Wales. Carmarthenshire was disputed between the Normans and the Welsh lords and many of the castles built around this time, first of wood and then stone, changed hands several times.[6] Following the Conquest of Wales by Edward I, the region was reorganized by the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284 into Carmarthenshire.[7] Edward I made Carmarthen the capital of this new county, establishing his courts of chancery and his exchequer there, and holding the Court of Great Sessions in Wales in the town.[5]

The Normans transformed Carmarthen into an international trading port, the only staple port in Wales. Merchants imported food and French wines and exported wool, pelts, leather, lead and tin. In the late medieval period the county's fortunes varied, as good and bad harvests occurred, increased taxes were levied by England, there were episodes of plague, and recruitment for wars removed the young men. Carmarthen was particularly susceptible to plague as it was brought in by flea-infested rats on board ships from southern France.[6]

In 1405, Owain Glyndŵr captured Carmarthen Castle and several other strongholds in the neighbourhood. However, when his support dwindled, the principal men of the county returned their allegiance to King Henry V.[5] During the English Civil War, Parliamentary forces under Colonel Roland Laugharne besieged and captured Carmarthen Castle but later abandoned the cause, and joined the Royalists. In 1648, Carmarthen Castle was recaptured by the Parliamentarians, and Oliver Cromwell ordered it to be slighted.[5]

The first industrial canal in Wales was built in 1768 to convey coal from the Gwendraeth Valley to the coast, and the following year, the earliest tramroad bridge was on the tramroad built alongside the canal.[6] During the Napoleonic Wars (1799–1815) there was increased demand for coal, iron and agricultural goods, and the county prospered. The landscape changed as much woodland was cleared to make way for more food production, and mills, power stations, mines and factories sprang up between Llanelli and Pembrey.[6] Carmarthenshire was at the centre of the Rebecca Riots around 1840, when local farmers and agricultural workers dressed as women and rebelled against higher taxes and tolls.[8]

On 1 April 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972, Carmarthenshire joined Cardiganshire and Pembrokeshire in the new county of Dyfed; Carmarthenshire was divided into three districts: Carmarthen, Llanelli and Dinefwr. Twenty-two years later this amalgamation was reversed when, under the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, the original county boundaries were reinstated.[9]

Geography

The county is bounded to the north by Ceredigion, to the east by Powys (historic county Brecknockshire), Neath Port Talbot (historic county Glamorgan) and Swansea (also Glamorgan), to the south by the Bristol Channel and to the west by Pembrokeshire. Much of the county is upland and hilly. The Black Mountain range dominates the east of the county, with the lower foothills of the Cambrian Mountains to the north across the valley of the River Towy. The south coast contains many fishing villages and sandy beaches. The highest point (county top) is the minor summit of Fan Foel, height 781 metres (2,562 ft), which is a subsidiary top of the higher mountain of Fan Brycheiniog, height 802.5 metres (2,633 ft) (the higher summit, as its name suggests, is actually across the border in Brecknockshire/Powys). Carmarthenshire is the largest historic county by area in Wales.[10]

The county is drained by several important rivers which flow southwards into the Bristol Channel, especially the River Towy, and its several tributaries, such as the River Cothi.[10] The Towy is the longest river flowing entirely within Wales.[11] Other rivers include the Loughor (which forms the eastern boundary with Glamorgan), the River Gwendraeth and the River Taf. The River Teifi forms much of the border between Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion, and there are a number of towns in the Teifi Valley which have communities living on either side of the river and hence in different counties. Carmarthenshire has a long coastline which is deeply cut by the estuaries of the Loughor in the east and the Gwendraeth, Tywi and Taf, which enter the sea on the east side of Carmarthen Bay.[10] The coastline includes notable beaches such as Pendine Sands and Cefn Sidan sands, and large areas of foreshore are uncovered at low tide along the Loughor and Towy estuaries.[12]

The principal towns in the county are Ammanford, Burry Port, Carmarthen, Kidwelly, Llanelli, Llandeilo, Newcastle Emlyn, Llandovery, St Clears, and Whitland. The principal industries are agriculture, forestry, fishing and tourism. Although Llanelli is by far the largest town in the county, the county town remains Carmarthen, mainly due to its central location.[10]

Carmarthenshire is predominantly an agricultural county, with only the southeastern area having any significant amount of industry. The best agricultural land is in the broad Tywi Valley, especially its lower reaches.[13] With its fertile land and agricultural produce, Carmarthenshire is known as the "Garden of Wales".[14] The lowest bridge over the river is at Carmarthen, and the Towi Estuary cuts the southwesterly part of the county, including Llansteffan and Laugharne, off from the more urban southeastern region. This area is also bypassed by the main communication routes into Pembrokeshire.[13] A passenger ferry service used to connect Ferryside with Llansteffan until the early part of the twentieth century.[15]

Economy

Agriculture and forestry are the main sources of income over most of the county of Carmarthenshire. On improved pastures, dairying is important and in the past, the presence of the railway enabled milk to be transported to the urban areas of England.[12] The creamery at Whitland is now closed but milk processing still takes place at Newcastle Emlyn where mozzarella cheese is made.[16] On upland pastures and marginal land, livestock rearing of cattle and sheep is the main agricultural activity.[13] The estuaries of the Loughor and Towy provide pickings for the cockle industry.[12]

Llanelli, Ammanford and the upper parts of the Gwendraeth Valley are situated on the South Wales Coalfield. The opencast mining activities in this region have now ceased but the old mining settlements with terraced housing remain, often centred on their nonconformist chapels. Kidwelly had a tin-plating industry in the eighteenth century, with Llanelli following not long after, so that by the end of the nineteenth century, Llanelli was the world-centre of the industry. There is little trace of these industrial activities today. Llanelli and Burry Port served at one time for the export of coal, but trade declined, as it did from the ports of Kidwelly and Carmarthen as their estuaries silted up. Country towns in the more agricultural part of the county still hold regular markets where livestock is traded.[13]

In the north of the county, in and around the Teifi Valley, there was a thriving woollen industry in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Here water-power provided the energy to drive the looms and other machinery at the mills. The village of Dre-fach Felindre at one time contained twenty-four mills and was known as the "Huddersfield of Wales". The demand for woollen cloth declined in the twentieth century and so did the industry.[17]

In 2014, West Wales was identified as the worst-performing region in the United Kingdom along with the South Wales Valleys. The gross value added economic indicator showed a figure of £14,763 per head in these regions, as compared with a GVA of £22,986 for Cardiff and the Vale of Glamorgan.[18] The Welsh Assembly Government is aware of this, and helped by government initiatives and local actions, opportunities for farmers to diversify have emerged. These include farm tourism, rural crafts, specialist food shops, farmers' markets and added-value food products.[19]

In 2015, in an attempt to boost the local economy, Carmarthenshire County Council produced a fifteen-year plan that highlighted six projects which it hoped would create five thousand new jobs. The sectors involved would be in the "creative industries, tourism, agri-food, advanced manufacturing, energy and environment, and financial and professional services".[20]

Local government

Carmarthenshire became an administrative county with a county council taking over functions from the Quarter Sessions under the Local Government Act 1888. Under the Local Government Act 1972, the administrative county of Carmarthenshire was abolished on 1 April 1974 and the area of Carmarthenshire became three districts within the new county of Dyfed : Carmarthen, Dinefwr and Llanelli. Under the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, Dyfed was abolished on 1 April 1996 and Carmarthenshire was re-established as a county.[21][22] The three districts united to form a unitary authority which had the same boundaries as the traditional county of Carmarthenshire. In 2003, the Clynderwen community council area was transferred to the administrative county of Pembrokeshire.[23]

Demography and the Welsh language

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, Carmarthen and Wrexham were the two most populous towns in Wales.[24][13] In 1931, the county's population was 171,445 and in 1951, 164,800. At the census in 2011, Carmarthenshire had a population of 183,777. Population levels have thus dipped and then increased again over the course of eighty years. The population density in Carmarthenshire is 0.8 persons per hectare compared to 1.5 per hectare in as a whole.[25]

Carmarthenshire was the most populous of the five historic counties of Wales to remain majority Welsh-speaking throughout the 20th century. According to the 1911 Census, 84.9 per cent of the county's population were Welsh-speaking (compared with 43.5 per cent in all of Wales), with 20.5 per cent of Carmarthenshire's overall population being monolingual Welsh-speakers.[26] In 1931, 82.3 per cent could speak Welsh and in 1951, 75.2 per cent.[27] By the 2001 census, 50.3 per cent of people living in Carmarthenshire could speak Welsh, with 39 per cent being able to read and write the language as well.[28] The 2011 census showed a further decline, with 43.9 per cent speaking Welsh, making it a minority language in the county for the first time.[29] However, the 2011 census also showed that 3,000 more people could understand spoken Welsh than in 2001 and that 60% of 5-14 year-olds could speak Welsh (a 5% increase since 2001).[30]

Landmarks

.jpg.webp)

With its strategic location and history, the county is rich in archaeological remains such as forts, earthworks and standing stones. Carn Goch is one of the most impressive Iron Age forts and stands on a hilltop near Llandeilo.[31] The Bronze Age is represented by chambered cairns and standing stones on Mynydd Llangyndeyrn, near Llangyndeyrn.[32] Castles that can be easily accessed include Carreg Cennen, Dinefwr, Kidwelly, Laugharne, Llansteffan and Newcastle Emlyn Castle. There are the ruinous remains of Talley Abbey, and the coastal village of Laugharne is for ever associated with Dylan Thomas. Stately homes in the county include Aberglasney House and Gardens, Golden Grove and Newton House.[33]

There are plenty of opportunities in the county for hiking, observing wildlife and admiring the scenery. These include Brechfa Forest, the Pembrey Country Park, the Millennium Coastal Park at Llanelli, the WWT Llanelli Wetlands Centre and the Carmel National Nature Reserve. There are large stretches of golden sands and the Wales Coast Path now provides a continuous walking route around the whole of Wales.[33]

The National Botanic Garden of Wales displays plants from Wales and from all around the world, and the Carmarthenshire County Museum, the National Wool Museum, the Parc Howard Museum, the Pendine Museum of Speed and the West Wales Museum of Childhood all provide opportunities to delve into the past. Dylan Thomas Boathouse where the author wrote many of his works can be visited, as can the Roman-worked Dolaucothi Gold Mines.[33]

Sports and leisure

Activities available in the county include rambling, cycling, fishing, kayaking, canoeing, sailing, horse riding, caving, abseiling and coasteering.[6] Carmarthen Town A.F.C. plays in the Cymru Premier. They won the Welsh Football League Cup in the 1995–96 season, and since then have won the Welsh Cup once and the Welsh League Cup twice.[34] Llanelli Town A.F.C. play in the Welsh Football League Division Two. The club won the Welsh premier league and Loosemores challenge cup in 2008 and won the Welsh Cup in 2011, but after experiencing financial difficulties, were wound up and reformed under the present title in 2013.[35] Scarlets is the regional professional rugby union team that plays in the Pro14, they play their home matches at their ground, Parc y Scarlets. Honours include winning the 2003/04 and 2016/17 Pro12. Llanelli RFC is a semi-professional rugby union team that play in the Welsh Premier Division, also playing home matches at Parc y Scarlets. Among many honours, they have been WRU Challenge Cup winners on fourteen occasions and frequently taken part in the Heineken Cup.[36] West Wales Raiders, based in Llanelli, represent the county in Rugby league.

Some sporting venues utilise disused industrial sites. Ffos Las racecourse was built on the site of an open cast coal mine after mining operations ceased. Opened in 2009, it was the first racecourse built in the United Kingdom for eighty years and has regular race-days.[37] Machynys is a championship golf course opened in 2005 and built as part of the Llanelli Waterside regeneration plan.[38] Pembrey Circuit is a motor racing circuit near Pembrey village, considered the home of Welsh motorsport, providing racing for cars, motorcycles, karts and trucks. It was opened in 1989 on a former airfield, is popular for testing and has hosted many events including the British Touring Car Championship twice.[39] The 2018 Tour of Britain cycling race started at Pembrey on 2 September 2018.[40]

Transport

Carmarthenshire is served by the main line railway service operated by Transport for Wales Rail which links London Paddington, Cardiff Central and Swansea to southwest Wales. The main hub is Carmarthen railway station where some services from the east terminate. The line continues westwards with several branches which serve Pembroke Dock, Milford Haven and Fishguard Harbour (for the ferry to Rosslare Europort and connecting trains to Dublin Connolly).[41] The Heart of Wales Line takes a scenic route through mid-Wales and links Llanelli with Craven Arms, from where passengers can travel on the Welsh Marches Line to Shrewsbury.[42]

The A40, A48, A484 and A485 converge on Carmarthen. The M4 route that links South Wales with London, terminates at junction 49, the Pont Abraham services, to continue northwest as the dual carriageway A48, and to finish with its junction with the A40 in Carmarthen.

Llanelli is linked to M4 junction 48 by the A4138. The A40 links Carmarthen to Llandeilo, Llandovery and Brecon to the east, and with St Clears, Whitland and Haverfordwest to the west. The A484 links Llanelli with Carmarthen by a coastal route and continues northwards to Cardigan, and via the A486 and A487 to Aberystwyth, and the A485 links Carmarthen to Lampeter.[43]

There are local bus services between the main centres of population,[44] and longer distance services to Cardiff and beyond. A bus service known as "Bwcabus" operates in the north of the county, offering customised transport to rural dwellers.[45]

Two heritage railways, the Gwili Railway and the Teifi Valley Railway, use the track of the Carmarthen and Cardigan Railway that at one time ran from Carmarthen to Newcastle Emlyn, but did not reach Cardigan.[46]

Cuisine

Carmarthenshire has rich, fertile farmland and a productive coast with estuaries providing a range of foods that motivate many home cooks and chefs.[47][48][49]

See also

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Carmarthenshire

- Custos Rotulorum of Carmarthenshire

- List of High Sheriffs of Carmarthenshire

- Carmarthenshire (UK Parliament constituency) for a list of MPs

- List of places in Carmarthenshire for an alphabetical list of towns and villages.

- Scheduled Monuments in Carmarthenshire

- List of schools in Carmarthenshire

- People from Carmarthenshire for a list of notable people from the county.

References

- "Carmarthenshire", British & World English Dictionary, Oxford Dictionaries Online

- "West Wales the worst performing economy in the UK". Carmarthen Journal. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Pettitt, Paul; White, Mark (2012). The British Palaeolithic: Hominin Societies at the Edge of the Pleistocene World. Routledge. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-415-67454-6.

- Pettitt and White, pp. 489, 497

- Lewis, Samuel (1849). "Carmarthenshire". British History Online. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- Grigg, Russell (2015). Little Book of Carmarthenshire. History Press Limited. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-7509-6346-6.

- Jones, Francis (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales Press. p. 35.

- Dylan Rees (2006). Carmarthenshire: The Concise History. University of Wales. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-7083-1949-9.

- "Local Government (Wales) Act 1994". The National Archives. Legislation.gov.uk. 1994. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Philip's (1994). Atlas of the World. Reed International. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-540-05831-9.

- "The River Towy: Facts About the Longest River in Wales". Primary Facts. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Carmarthenshire Beaches". A Guide to the Beaches of Pembrokeshire and West Wales. FBM Holidays. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Lloyd, Thomas; Orbach, Julian; Scourfield, Robert (2006). Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion. Yale University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-300-10179-1.

- "Carmarthenshire County Council, Tourism & Marketing Division: Discovering Carmarthenshire". Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- "Llansteffan". Llansteffan Tourism Association. 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- "Our locations: Newcastle Emlyn". Dairy Partners. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- The Woollen Mills of Wales, a leaflet from National Museum Wales.

- "West Wales the worst performing economy in the UK". Carmarthen Journal. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Nienaber, Birte (2016). Globalization and Europe's Rural Regions. Routledge. pp. 76–83. ISBN 978-1-317-12709-3.

- Farrell, Stephen (23 November 2015). "Fifteen-year plan to boost Carmarthenshire economy". Insider Media Limited. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Schaefer, Christina K. (1999). Instant Information on the Internet!: A Genealogist's No-frills Guide to the British Isles. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-8063-1614-7.

- Breverton, Terry (2012). Wales: A Historical Companion. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-4456-0990-4.

- "Community ref 11,: Clunderwen". Review of Communities. Pembrokeshire County Council. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- POWELL, NIA (2005). "Do numbers count? Towns in early modern Wales". Urban History. 32 (1): 46–67. ISSN 0963-9268.

- "Census information". 2011 Census. Sir Gar Carmarthenshire. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- "Language spoken in Wales, 1911, Page iv". histpop.org.

- "The Distribution of the Welsh Language, 1931–1951". JSTOR 1790647. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Welsh Language Statistics". Statistics and Census Information: Population and Demography. Carmarthenshire County Council. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- "Carmarthenshire to research Welsh-language speaker drop". BBC News. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- "The Welsh Language in Carmarthenshire" (PDF).

- "Llandeilo History: Prehistory". Llandeilo through the ages. Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Mynydd Llangyndeyrn Mountain". Discovering Carmarthenshire. Carmarthenshire County Council. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Discovering Carmarthenshire". Carmarthenshire County Council. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Carmarthen Town Club History". Football Club History Database (F.C.H.D.). Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Llanelli Town AFC Club Information from Football Association of Wales". Football Association of Wales. Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "History of Llanelli RFC". Llanelli RFC. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Ffos Las: Racing and Events". Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Machynys Clwb Golff". Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Pembrey Circuit". Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Geraint Thomas and Chris Froome start Tour of Britain". BBC News. 2 September 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Route 14 South and Central Wales and Borders" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Williams, Sally (29 March 2013). "Heart of Wales railway line in danger". Wales Online. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Concise Road Atlas: Britain. AA Publishing. 2015. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0-7495-7743-8.

- Le Nevez, Catherine; Whitfield, Paul (2012). The Rough Guide to Wales. Rough Guides Limited. pp. 257–267. ISBN 978-1-4093-5902-9.

- "Bwcabus". Bwcabus. 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- "Local railway history". Teifi Valley Railway. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved 7 August 2010

- Pressdee, C., ‘Colin Pressdee’s Welsh Coastal Cookery, BBC Books, 1995, ISBN 0-563-37136-6

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved 7 August 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carmarthenshire. |

- Carmarthenshire County Council

- Carmarthenshire County Council - Tourism & Marketing Division : Discover Carmarthenshire

- Carmarthenshire: Official site from South West Wales Tourist Board

- GENUKI: Research sources for Carmarthenshire

- Carmarthenshire at Curlie