Catholic League (French)

The Catholic League of France (French: Ligue catholique), (La Sainte Ligue, Holy League), was a major participant in the French Wars of Religion. It was formed in 1576 by Henry I, Duke of Guise "...to oppose concessions granted to the Protestants (Huguenots) by King Henry III. Although the basic reason behind the League’s formation was the defense of the Catholic religion, ...the desire to limit the king’s power" was also a motivating force.[1] Pope Sixtus V, Philip II of Spain, and the Jesuits were supporters of this Catholic party.

| Catholic League | |

|---|---|

| Ligue catholique | |

.svg.png.webp) Flag of the League, ca. 1590 | |

| Founders | Henry I, Duke of Guise and Charles de Bourbon |

| Dates of operation | 1576 – 1577 1584 – 1595 |

| Allegiance | Crown of France (de jure) Crown of Spain (de facto) |

| Motives | Edict of Beaulieu |

| Headquarters | Paris and Péronne |

| Ideology | Anti-Protestantism Ultramontanism |

| Size | Unknown |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | |

| Battles and wars | |

The Catholic League's political origins

Confraternities and leagues were established by French Catholics to counter the growing power of the Lutherans, Calvinists and members of the Reformed Church of France.

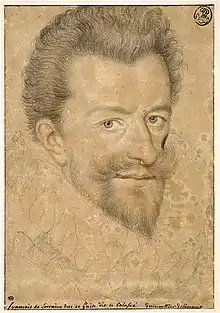

Under the leadership of Henry I, Duke of Guise, the Catholic confraternities and leagues were united as the Catholic League. Guise used the League not only to defend the Catholic cause but also as a political tool in an attempt to usurp the French throne.[2] The Catholic League aimed to preempt any seizure of power by the Huguenots and to protect French Catholics' right to worship. Members saw their fight against Calvinism (the primary branch of Protestantism in France) as a Crusade against heresy. During a series of bloody clashes, the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598), between Catholics and Protestants, the Catholic League formed in an attempt to break the power of the Calvinist gentry once and for all.

In Nantes, the League was a reaction on the part of the city leaders to the King's failure to protect them against both Huguenot forces and the royal military.[3] They joined with the rebellion of Philippe Emmanuel, Duke of Mercœur, governor of Brittany. Invoking the hereditary rights of his wife, Marie de Luxembourg, daughter of Sébastien, Duke of Penthièvre. Mercœur endeavoured to make himself independent in that province from 1589 onwards, and organized a government at Nantes, proclaiming their young son, Philippe de Lorraine-Mercœur, (d. 1590), "prince and duke of Brittany".

The Catholic League saw the French throne under Henry III as too conciliatory towards the Huguenots. The League, similar to hardline Calvinists, disapproved of Henry III's attempts to mediate any coexistence between the Huguenots and Catholics. The Catholic League also saw moderate French Catholics, known as Politiques, as a serious threat. The Politiques were tired of the many tit for tat killings and were willing to negotiate peaceful coexistence rather than escalating the war.

History of the League

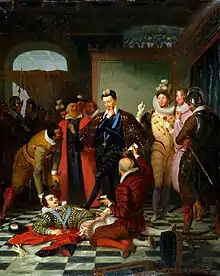

The League immediately began to exert pressure on Henry III of France. Faced with this mounting opposition (spurred in part because the heir to the French throne, Henry of Navarre, was a Huguenot) he canceled the Peace of La Rochelle, re-criminalizing Protestantism and beginning a new chapter in the French Wars of Religion. However, Henry also saw the danger posed by the Duke of Guise, who was gaining more and more power. In the Day of the Barricades, King Henry III was forced to flee Paris, which resulted in Henry, Duke of Guise becoming the de facto ruler of France. Afraid of being deposed and assassinated, the King decided to strike first. On December 23, 1588, Henry III's guardsmen assassinated the Duke and his brother, Louis II and the Duke's son was imprisoned in the Bastille.

However, this move did little to consolidate the King's power and enraged both the surviving Guises and their followers. As a result, the King fled Paris and joined forces with Henry of Navarre, the throne's Calvinist heir presumptive. Both the King and Henry of Navarre began building an army with which to besiege Paris. On August 1, 1589, as the two Henrys besieged the city and prepared for their final assault, Jacques Clément, a Dominican lay brother with ties to the League, successfully infiltrated the King's entourage, dressed as a priest, and assassinated him. This was retaliation for the killing of the Duke of Guise and his brother. As he lay dying, the King begged Henry of Navarre to convert to Catholicism, calling it the only way to prevent further bloodshed. However, the King's death threw the army into disarray and Henry of Navarre was forced to lift the siege.

Although Henry of Navarre was now the legitimate King of France, the League's armies were so strong that he was unable to capture Paris and was forced to retreat south. Using arms and military advisors provided by Elizabeth I of England, he achieved several military victories. However, he was unable to overcome the superior forces of the League, which commanded the loyalty of most Frenchmen and had the support of Philip II of Spain. The League then attempted to declare the Cardinal of Bourbon, Henry's uncle, as king Charles X of France on November 21, 1589, but his status as a prisoner of Henry of Navarre and his death in May 1590 removed all legitimacy from this gesture. Furthermore, the Cardinal refused to usurp the throne and supported his nephew, although to little avail.

Unable to provide a viable candidate for the French throne (the League's support was split among several candidates, including Isabella, a Spanish princess, which made them appear to no longer have French interests at heart), the League's position weakened, but remained strong enough to keep Henry from besieging Paris. Finally, in a bid to peacefully end the war, Henry of Navarre was received into the Church on July 25, 1593 and was recognized as King Henry IV on February 27, 1594. He is purported to have said later, "Paris is well worth a Mass," though some scholars question the veracity of this quotation.

Under the rule of King Henry IV, the Edict of Nantes was passed, granting religious toleration and limited autonomy to the Huguenots and ensuring a lasting peace for France. Moreover, the Catholic League now lacked the threat of a Calvinist king and gradually disintegrated.

Assessment

Historian Mack Holt argues that historians have sometimes over-emphasised the political role of the League at the expense of its religious and devotional character:

What is the final judgement on the Catholic League? It would be a mistake to treat it, as so many historians have, as nothing more than a body motivated purely by partisan politics or social tensions. While political and social pressures were doubtless present, and even significant in the case of the Sixteen in Paris, to focus on these factors exclusively overlooks a very different face of the League. For all its political and internecine wrangling, the League was still very much a Holy Union. Its religious role was significant, as the League was the conduit between the Tridentine spirituality of the Catholic Reformation and the seventeenth century devots. Often overlooked is the emphasis the League placed on the internal and spiritual renewal of the earthly city. Moving beyond the communal religion of the later Middle Ages, the League focused on internalizing faith as a cleansing and purifying agent. New religious orders and confraternities were founded in League towns, and the gulf separating laity and clergy was often bridged as clerics joined aldermen in the Hotel de Ville where both became the epitome of goodly magistrates. To overlook the religious side of the League is to overlook the one bond that did keep the Holy Union holy as well as united.[4]

See also

- Catholic League (disambiguation) for other similarly named coalitions.

- Philippe Emmanuel, Duke of Mercœur, one of its leaders

- Politiques, term applied to those who resisted the French Catholic League

Citations

References

- Baumgartner, Frederic J. Radical Reactionaries: The Political Thought of the French Catholic League (Geneva:Droz) 1976

- Jensen, De Lamar Diplomacy and Dogmatism: Bernardino de Mendoza and the French Catholic League Mendoza's role in Philip II's intervening foreign policy.

- Carroll, Warren H. The Cleaving of Christendom. A History of Christendom, volume 4, Christendom Press, 2004.

- Holt, Mack P. The French Wars of Religion, 1562-1629, page 149-150. New York, 1995.

- Konnert, Mark "Local politics in the French Wars of Religion"

- Leonardo, Dalia M. "Cut off this rotten member": The Rhetoric of Heresy, Sin, and Disease in the Ideology of the French Catholic League" The Catholic Historical Review 88.2, (April 2002:247-262).

- Yardeni, Myriam "La Conscience nationale en France pendant les guerres de religion"