Chad

Chad (/tʃæd/ (![]() listen); Arabic: تشاد Tšād, Arabic pronunciation: [tʃaːd]; French: Tchad, pronounced [tʃa(d)]), officially known as the Republic of Chad (Arabic: جمهورية تْشَاد Jumhūriyyat Tšād; French: République du Tchad), is a landlocked country in north-central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon to the south-west, Nigeria to the southwest (at Lake Chad), and Niger to the west.

listen); Arabic: تشاد Tšād, Arabic pronunciation: [tʃaːd]; French: Tchad, pronounced [tʃa(d)]), officially known as the Republic of Chad (Arabic: جمهورية تْشَاد Jumhūriyyat Tšād; French: République du Tchad), is a landlocked country in north-central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon to the south-west, Nigeria to the southwest (at Lake Chad), and Niger to the west.

Republic of Chad | |

|---|---|

Motto:

| |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | N'Djamena 12°06′N 16°02′E |

| Official languages | Arabic • French |

| Ethnic groups (2009 Census[1]) | |

| Demonym(s) | Chadian |

| Government | Unitary dominant-party presidential republic |

• President | Idriss Déby |

| Haroun Kabadi | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Independence | |

• Republic established | 28 November 1958 |

• from France | 11 August 1960 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,284,000 km2 (496,000 sq mi)[2] (20th) |

• Water (%) | 1.9 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | 16,244,513[3] (70th) |

• 2009 census | 11,039,873[4] |

• Density | 8.6/km2 (22.3/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $30 billion[5] (123rd) |

• Per capita | $2,428[5] (168th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $11 billion[5] (130th) |

• Per capita | $890[5] (151st) |

| Gini (2011) | 43.3[6] medium |

| HDI (2019) | low · 187th |

| Currency | Central African CFA franc (XAF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (WAT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +235 |

| ISO 3166 code | TD |

| Internet TLD | .td |

Chad has several regions: a desert zone in the north, an arid Sahelian belt in the centre and a more fertile Sudanian Savanna zone in the south. Lake Chad, after which the country is named, is the largest wetland in Chad and the second-largest in Africa. The capital N'Djamena is the largest city. Chad's official languages are Arabic and French. Chad is home to over 200 different ethnic and linguistic groups. Islam (51.8%) and Christianity (44.1%) are the main religions practiced in Chad.[8]

Beginning in the 7th millennium BC, human populations moved into the Chadian basin in great numbers. By the end of the 1st millennium AD, a series of states and empires had risen and fallen in Chad's Sahelian strip, each focused on controlling the trans-Saharan trade routes that passed through the region.

France conquered the territory by 1920 and incorporated it as part of French Equatorial Africa. In 1960, Chad obtained independence under the leadership of François Tombalbaye. Resentment towards his policies in the Muslim north culminated in the eruption of a long-lasting civil war in 1965. In 1979 the rebels conquered the capital and put an end to the South's hegemony. But, the rebel commanders fought amongst themselves until Hissène Habré defeated his rivals. Chadian–Libyan conflict erupted in 1978 by the Libyan invasion which stopped in 1987 with a French military intervention (Operation Épervier). Hissène Habré was overthrown in turn in 1990 by his general Idriss Déby. With French support, a modernization of the Chadian armed forces was initiated in 1991. Since 2003 the Darfur crisis in Sudan has spilt over the border and destabilised the nation. Poor already, the nation and people struggled to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of Sudanese refugees who live in and around camps in eastern Chad.

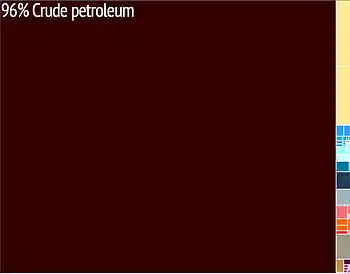

While many political parties are active, power lies firmly in the hands of President Déby and his political party, the Patriotic Salvation Movement. Chad remains plagued by political violence and recurrent attempted coups d'état. Chad is one of the poorest and most corrupt countries in the world; most inhabitants live in poverty as subsistence herders and farmers. Since 2003 crude oil has become the country's primary source of export earnings, superseding the traditional cotton industry. Chad has a poor human rights record, with frequent abuses such as arbitrary imprisonment, extrajudicial killings, and limits on civil liberties by both security forces and armed militias.

History

In the 7th millennium BCE, ecological conditions in the northern half of Chadian territory favored human settlement, and its population increased considerably. Some of the most important African archaeological sites are found in Chad, mainly in the Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region; some date to earlier than 2000 BCE.[9][10]

For more than 2,000 years, the Chadian Basin has been inhabited by agricultural and sedentary people. The region became a crossroads of civilizations. The earliest of these were the legendary Sao, known from artifacts and oral histories. The Sao fell to the Kanem Empire,[11][12] the first and longest-lasting of the empires that developed in Chad's Sahelian strip by the end of the 1st millennium AD. Two other states in the region, Sultanate of Bagirmi and Wadai Empire emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries. The power of Kanem and its successors was based on control of the trans-Saharan trade routes that passed through the region.[10] These states, at least tacitly Muslim, never extended their control to the southern grasslands except to raid for slaves.[13] In Kanem, about a third of the population were slaves.[14]

French colonial expansion led to the creation of the Territoire Militaire des Pays et Protectorats du Tchad in 1900. By 1920, France had secured full control of the colony and incorporated it as part of French Equatorial Africa.[16] French rule in Chad was characterised by an absence of policies to unify the territory and sluggish modernisation compared to other French colonies.[17]

The French primarily viewed the colony as an unimportant source of untrained labour and raw cotton; France introduced large-scale cotton production in 1929. The colonial administration in Chad was critically understaffed and had to rely on the dregs of the French civil service. Only the Sara of the south was governed effectively; French presence in the Islamic north and east was nominal. The educational system was affected by this neglect.[10][17]

After World War II, France granted Chad the status of overseas territory and its inhabitants the right to elect representatives to the National Assembly and a Chadian assembly. The largest political party was the Chadian Progressive Party (French: Parti Progressiste Tchadien, PPT), based in the southern half of the colony. Chad was granted independence on 11 August 1960 with the PPT's leader, François Tombalbaye, an ethnic Sara, as its first president.[10][18][19]

Two years later, Tombalbaye banned opposition parties and established a one-party system. Tombalbaye's autocratic rule and insensitive mismanagement exacerbated inter-ethnic tensions. In 1965, Muslims in the north, led by the National Liberation Front of Chad (French: Front de libération nationale du Tchad, FRONILAT), began a civil war. Tombalbaye was overthrown and killed in 1975,[20] but the insurgency continued. In 1979 the rebel factions led by Hissène Habré took the capital, and all central authority in the country collapsed. Armed factions, many from the north's rebellion, contended for power.[21][22]

The disintegration of Chad caused the collapse of France's position in the country. Libya moved to fill the power vacuum and became involved in Chad's civil war.[23] Libya's adventure ended in disaster in 1987; the French-supported president, Hissène Habré, evoked a united response from Chadians of a kind never seen before[24] and forced the Libyan army off Chadian soil.[25]

Habré consolidated his dictatorship through a power system that relied on corruption and violence with thousands of people estimated to have been killed under his rule.[26][27] The president favoured his own Toubou ethnic group and discriminated against his former allies, the Zaghawa. His general, Idriss Déby, overthrew him in 1990.[28] Attempts to prosecute Habré led to his placement under house arrest in Senegal in 2005; in 2013, Habré was formally charged with war crimes committed during his rule.[29] In May 2016, he was found guilty of human-rights abuses, including rape, sexual slavery, and ordering the killing of 40,000 people, and sentenced to life in prison.[30]

2014.png.webp)

Déby attempted to reconcile the rebel groups and reintroduced multiparty politics. Chadians approved a new constitution by referendum, and in 1996, Déby easily won a competitive presidential election. He won a second term five years later.[31] Oil exploitation began in Chad in 2003, bringing with it hopes that Chad would, at last, have some chances of peace and prosperity. Instead, internal dissent worsened, and a new civil war broke out. Déby unilaterally modified the constitution to remove the two-term limit on the presidency; this caused an uproar among the civil society and opposition parties.[32]

In 2006 Déby won a third mandate in elections that the opposition boycotted. Ethnic violence in eastern Chad has increased; the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has warned that a genocide like that in Darfur may yet occur in Chad.[33] In 2006 and in 2008 rebel forces attempted to take the capital by force, but failed on both occasions.[34] An agreement for the restoration of harmony between Chad and Sudan, signed 15 January 2010, marked the end of a five-year war.[35] The fix in relations led to the Chadian rebels from Sudan returning home, the opening of the border between the two countries after seven years of closure, and the deployment of a joint force to secure the border. In May 2013, security forces in Chad foiled a coup against President Idriss Déby that had been in preparation for several months.[36]

Chad is currently one of the leading partners in a West African coalition in the fight against Boko Haram. Chad has also been included on Presidential Proclamation 9645, the expanded version of United States president Donald Trump's Executive Order 13780, which restricts entry by nationals from 8 countries, including Chad, into the US. This move has angered the Chadian government.[37]

Geography, climate and environment

At 1,284,000 square kilometres (496,000 sq mi),[2] Chad is the world's 20th-largest country. It is slightly smaller than Peru and slightly larger than South Africa.[38][39] Chad is in north central Africa, lying between latitudes 7° and 24°N, and 13° and 24°E.[40]

Chad is bounded to the north by Libya, to the east by Sudan, to the west by Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon, and to the south by the Central African Republic. The country's capital is 1,060 kilometres (660 mi) from the nearest seaport, Douala, Cameroon.[40][41] Because of this distance from the sea and the country's largely desert climate, Chad is sometimes referred to as the "Dead Heart of Africa".[42]

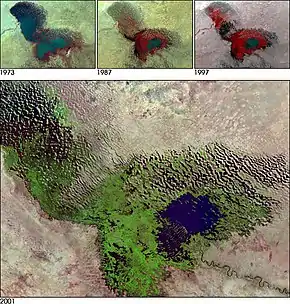

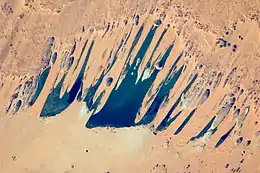

The dominant physical structure is a wide basin bounded to the north and east by the Ennedi Plateau and Tibesti Mountains, which include Emi Koussi, a dormant volcano that reaches 3,414 metres (11,201 ft) above sea level. Lake Chad, after which the country is named (and which in turn takes its name from the Kanuri word for "lake"[43]), is the remains of an immense lake that occupied 330,000 square kilometres (130,000 sq mi) of the Chad Basin 7,000 years ago.[40] Although in the 21st century it covers only 17,806 square kilometres (6,875 sq mi), and its surface area is subject to heavy seasonal fluctuations,[44] the lake is Africa's second largest wetland.[45]

Chad is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: East Sudanian savanna, Sahelian Acacia savanna, Lake Chad flooded savanna, East Saharan montane xeric woodlands, South Saharan steppe and woodlands, and Tibesti-Jebel Uweinat montane xeric woodlands.[46] The region's tall grasses and extensive marshes make it favourable for birds, reptiles, and large mammals. Chad's major rivers—the Chari, Logone and their tributaries—flow through the southern savannas from the southeast into Lake Chad.[40][47]

Climate

Each year a tropical weather system known as the intertropical front crosses Chad from south to north, bringing a wet season that lasts from May to October in the south, and from June to September in the Sahel.[48] Variations in local rainfall create three major geographical zones. The Sahara lies in the country's northern third. Yearly precipitations throughout this belt are under 50 millimetres (2.0 in); only occasional spontaneous palm groves survive, all of them south of the Tropic of Cancer.[41]

The Sahara gives way to a Sahelian belt in Chad's centre; precipitation there varies from 300 to 600 mm (11.8 to 23.6 in) per year. In the Sahel, a steppe of thorny bushes (mostly acacias) gradually gives way to the south to East Sudanian savanna in Chad's Sudanese zone. Yearly rainfall in this belt is over 900 mm (35.4 in).[41]

Wildlife

Chad's animal and plant life correspond to the three climatic zones. In the Saharan region, the only flora is the date-palm groves of the oasis. Palms and acacia trees grow in the Sahelian region. The southern, or Sudanic, zone consists of broad grasslands or prairies suitable for grazing. As of 2002, there were at least 134 species of mammals, 509 species of birds (354 species of residents and 155 migrants), and over 1,600 species of plants throughout the country.[49][50]

Elephants, lions, buffalo, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, giraffes, antelopes, leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and many species of snakes are found here, although most large carnivore populations have been drastically reduced since the early 20th century.[49][51] Elephant poaching, particularly in the south of the country in areas such as Zakouma National Park, is a severe problem. The small group of surviving West African crocodiles in the Ennedi Plateau represents one of the last colonies known in the Sahara today.[52]

Extensive deforestation has resulted in loss of trees such as acacias, baobab, dates and palm trees. Chad had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 6.18/10, ranking it 83rd globally out of 172 countries.[53] This has also caused loss of natural habitat for wild animals; one of the main reasons for this is also hunting and livestock farming by increasing human settlements. Populations of animals like lions, leopards and rhino have fallen significantly.[54]

Efforts have been made by the Food and Agriculture Organization to improve relations between farmers, agro-pastoralists and pastoralists in the Zakouma National Park (ZNP), Siniaka-Minia, and Aouk reserve in southeastern Chad to promote sustainable development.[55] As part of the national conservation effort, more than 1.2 million trees have been replanted to check the advancement of the desert, which incidentally also helps the local economy by way of financial return from acacia trees, which produce gum arabic, and also from fruit trees.[54]

Poaching is a serious problem in the country, particularly of elephants for the profitable ivory industry and a threat to lives of rangers even in the national parks such as Zakouma. Elephants are often massacred in herds in and around the parks by organized poaching.[56] The problem is worsened by the fact that the parks are understaffed and that a number of wardens have been murdered by poachers.[57]

Demographics

| Year | Million |

|---|---|

| 1950 | 2.5 |

| 2000 | 8.3 |

| 2018 | 15.5 |

Chad's national statistical agency projected the country's 2015 population between 13,630,252 and 13,679,203, with 13,670,084 as its medium projection; based on the medium projection, 3,212,470 people lived in urban areas and 10,457,614 people lived in rural areas.[3] The country's population is young: an estimated 47.3% is under 15. The birth rate is estimated at 42.35 births per 1,000 people, the mortality rate at 16.69. The life expectancy is 52 years.[60]

Chad's population is unevenly distributed. Density is 0.1/km2 (0.26/sq mi) in the Saharan Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Region but 52.4/km2 (136/sq mi) in the Logone Occidental Region. In the capital, it is even higher.[41] About half of the nation's population lives in the southern fifth of its territory, making this the most densely populated region.[61]

Urban life is concentrated in the capital, whose population is mostly engaged in commerce. The other major towns are Sarh, Moundou, Abéché and Doba, which are considerably smaller but growing rapidly in population and economic activity.[40] Since 2003, 230,000 Sudanese refugees have fled to eastern Chad from war-ridden Darfur. With the 172,600 Chadians displaced by the civil war in the east, this has generated increased tensions among the region's communities.[62][63]

Polygamy is common, with 39% of women living in such unions. This is sanctioned by law, which automatically permits polygamy unless spouses specify that this is unacceptable upon marriage.[64] Although violence against women is prohibited, domestic violence is common. Female genital mutilation is also prohibited, but the practice is widespread and deeply rooted in tradition; 45% of Chadian women undergo the procedure, with the highest rates among Arabs, Hadjarai, and Ouaddaians (90% or more). Lower percentages were reported among the Sara (38%) and the Toubou (2%). Women lack equal opportunities in education and training, making it difficult for them to compete for the relatively few formal-sector jobs. Although property and inheritance laws based on the French code do not discriminate against women, local leaders adjudicate most inheritance cases in favour of men, according to traditional practice.[65]

Largest cities, towns, and municipalities

| Rank | City | Population | Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 Census[66] | 2009 Census[66] | |||

| 1. | N'Djaména | 530,965 | 951,418 | N'Djaména |

| 2. | Moundou | 99,530 | 137,251 | Logone Occidental |

| 3. | Abéché | 54,628 | 97,963 | Ouaddaï |

| 4. | Sarh | 75,496 | 97,224 | Moyen-Chari |

| 5. | Kélo | 31,319 | 57,859 | Tandjilé |

| 6. | Am Timan | 21,269 | 52,270 | Salamat |

| 7. | Doba | 17,920 | 49,647 | Logone Oriental |

| 8. | Pala | 26,116 | 49,461 | Mayo-Kebbi Ouest |

| 9. | Bongor | 20,448 | 44,578 | Mayo-Kebbi Est |

| 10. | Goz Beïda | 3,083 | 41,248 | Sila |

Ethnic groups

The peoples of Chad carry significant ancestry from Eastern, Central, Western, and Northern Africa.[67]

Chad has more than 200 distinct ethnic groups,[68] which create diverse social structures. The colonial administration and independent governments have attempted to impose a national society, but for most Chadians the local or regional society remains the most important influence outside the immediate family. Nevertheless, Chad's people may be classified according to the geographical region in which they live.[10][40]

In the south live sedentary people such as the Sara, the nation's main ethnic group, whose essential social unit is the lineage. In the Sahel sedentary peoples live side by side with nomadic ones, such as the Arabs, the country's second major ethnic group. The north is inhabited by nomads, mostly Toubous.[10][40]

Languages

Chad's official languages are Arabic and French, but over 100 languages and dialects are spoken. Due to the important role played by itinerant Arab traders and settled merchants in local communities, Chadian Arabic has become a lingua franca.[10]

Religion

Chad is a religiously diverse country. Various estimates, including from Pew Research Center in 2010, found that 51.8 - 57.7% of the population was Muslim, while 39% - 44.1% were Christian.[69] 21.5% were Catholic and a further 16.6% were Protestant.[70][71] Among Muslims, 48% professed to be Sunni, 21% Shia, 4% Ahmadi and 23% just Muslim.[72] A small proportion of the population continues to practice indigenous religions. Animism includes a variety of ancestor and place-oriented religions whose expression is highly specific. Islam is expressed in diverse ways; for example, 55% of Muslim Chadians belong to Sufi orders.[72] Christianity arrived in Chad with the French and American missionaries; as with Chadian Islam, it syncretises aspects of pre-Christian religious beliefs.[10] Muslims are largely concentrated in northern and eastern Chad, and animists and Christians live primarily in southern Chad and Guéra.[40] The constitution provides for a secular state and guarantees religious freedom; different religious communities generally co-exist without problems.[73]

The majority of Muslims in the country are adherents of a moderate branch of mystical Islam (Sufism). Its most common expression is the Tijaniyah, an order followed by the 35% of Chadian Muslims which incorporates some local African religious elements.[72] A small minority of the country's Muslims hold more fundamentalist practices, which, in some cases, may be associated with Saudi-oriented Salafi movements.[73]

Roman Catholics represent the largest Christian denomination in the country. Most Protestants, including the Nigeria-based "Winners' Chapel", are affiliated with various evangelical Christian groups. Members of the Baháʼí and Jehovah's Witnesses religious communities also are present in the country. Both faiths were introduced after independence in 1960 and therefore are considered to be "new" religions in the country.[73]

Chad is home to foreign missionaries representing both Christian and Islamic groups. Itinerant Muslim preachers, primarily from Sudan, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan, also visit. Saudi Arabian funding generally supports social and educational projects and extensive mosque construction.[73]

Government and politics

Chad's constitution provides for a strong executive branch headed by a president who dominates the political system. The president has the power to appoint the prime minister and the cabinet, and exercises considerable influence over appointments of judges, generals, provincial officials and heads of Chad's para-statal firms.[75] In cases of grave and immediate threat, the president, in consultation with the National Assembly, may declare a state of emergency. The president is directly elected by popular vote for a five-year term; in 2005 constitutional term limits were removed,[76] allowing a president to remain in power beyond the previous two-term limit.[76] Most of Déby's key advisers are members of the Zaghawa ethnic group, although southern and opposition personalities are represented in government.[68][77]

Chad's legal system is based on French civil law and Chadian customary law where the latter does not interfere with public order or constitutional guarantees of equality. Despite the constitution's guarantee of judicial independence, the president names most key judicial officials. The legal system's highest jurisdictions, the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Council, have become fully operational since 2000. The Supreme Court is made up of a chief justice, named by the president, and 15 councillors, appointed for life by the president and the National Assembly. The Constitutional Court is headed by nine judges elected to nine-year terms. It has the power to review legislation, treaties and international agreements prior to their adoption.[68][77]

The National Assembly makes legislation. The body consists of 155 members elected for four-year terms who meet three times per year. The Assembly holds regular sessions twice a year, starting in March and October, and can hold special sessions when called by the prime minister. Deputies elect a National Assembly president every two years. The president must sign or reject newly passed laws within 15 days. The National Assembly must approve the prime minister's plan of government and may force the prime minister to resign through a majority vote of no confidence. However, if the National Assembly rejects the executive branch's programme twice in one year, the president may disband the Assembly and call for new legislative elections. In practice, the president exercises considerable influence over the National Assembly through his party, the Patriotic Salvation Movement (MPS), which holds a large majority.[68]

Until the legalisation of opposition parties in 1992, Déby's MPS was the sole legal party in Chad.[68] Since then, 78 registered political parties have become active.[65] In 2005, opposition parties and human rights organisations supported the boycott of the constitutional referendum that allowed Déby to stand for re-election for a third term[78] amid reports of widespread irregularities in voter registration and government censorship of independent media outlets during the campaign.[79] Correspondents judged the 2006 presidential elections a mere formality, as the opposition deemed the polls a farce and boycotted them.[80]

Chad is listed as a failed state by the Fund for Peace (FFP). In 2007 Chad had the seventh highest score on the failed state index. Since then the trend has been upwards each year. Chad had the fourth highest score (behind Sudan) on the Failed State Index of 2012 and as of 2013, is ranked fifth.[81] Corruption is rife at all levels; Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index for 2005 named Chad (tied with Bangladesh) as the most corrupt country in the world.[82] Chad's ranking on the index has improved only marginally in recent years. Since its first inclusion on the index in 2004, Chad's best score has been 2/10 for 2011.[83] Critics of President Déby have accused him of cronyism and tribalism.[84]

In southern Chad, bitter conflicts over land are becoming more and more common. They frequently turn violent. Long-standing community culture is being eroded – and so are the livelihoods of many farmers.[85]

Homosexual acts are illegal and can be punished by 15 to 20 years in prison.[86] In December 2016, Chad passed a law criminalising both male and female same-sex sexual activity by a vote of 111 to 1.[87]

Internal opposition and foreign relations

Déby faces armed opposition from groups who are deeply divided by leadership clashes but united in their intention to overthrow him.[88] These forces stormed the capital on 13 April 2006, but were ultimately repelled. Chad's greatest foreign influence is France, which maintains 1,000 soldiers in the country. Déby relies on the French to help repel the rebels, and France gives the Chadian army logistical and intelligence support for fear of a complete collapse of regional stability.[89] Nevertheless, Franco-Chadian relations were soured by the granting of oil drilling rights to the American Exxon company in 1999.[90]

There have been numerous rebel groups in Chad throughout the last few decades. In 2007, a peace treaty was signed that integrated United Front for Democratic Change or FUC soldiers into the Chadian Army.[91] The Movement for Justice and Democracy in Chad or MDJT also clashed with government forces in 2003 in an attempt to overthrow President Idriss Déby. In addition, there have been various conflicts with Khartoum's Janjaweed rebels in eastern Chad, who killed civilians by use of helicopter gunships.[92] Presently, the Union of Resistance Forces or UFR are a rebel group that continues to battle with the government of Chad. In 2010, the UFR reportedly had a force estimating 6,000 men and 300 vehicles.[93]

Administrative divisions

Since 2012 Chad has been divided into 23 regions.[94] The subdivision of Chad in regions came about in 2003 as part of the decentralisation process, when the government abolished the previous 14 prefectures. Each region is headed by a presidentially appointed governor. Prefects administer the 61 departments within the regions.[95] The departments are divided into 200 sub-prefectures, which are in turn composed of 446 cantons.[96][97]

The cantons are scheduled to be replaced by communautés rurales, but the legal and regulatory framework has not yet been completed.[98] The constitution provides for decentralised government to compel local populations to play an active role in their own development.[99] To this end, the constitution declares that each administrative subdivisions be governed by elected local assemblies,[100] but no local elections have taken place,[101] and communal elections scheduled for 2005 have been repeatedly postponed.[65]

Military

The CIA World Factbook estimates the military budget of Chad to be 4.2% of GDP as of 2006.[102] Given the then GDP ($7.095 bln) of the country, military spending was estimated to be about $300 million. This estimate however dropped after the end of the Civil war in Chad (2005–2010) to 2.0%[103] as estimated by the World Bank for the year 2011.

Economy

The United Nations' Human Development Index ranks Chad as the seventh poorest country in the world, with 80% of the population living below the poverty line. The GDP (purchasing power parity) per capita was estimated as US$1,651 in 2009.[5] Chad is part of the Bank of Central African States, the Customs and Economic Union of Central Africa (UDEAC) and the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[104]

Chad's currency is the CFA franc. In the 1960s, the mining industry of Chad produced sodium carbonate, or natron. There have also been reports of gold-bearing quartz in the Biltine Prefecture. However, years of civil war have scared away foreign investors; those who left Chad between 1979 and 1982 have only recently begun to regain confidence in the country's future. In 2000 major direct foreign investment in the oil sector began, boosting the country's economic prospects.[38][68]

An uneven inclusion into the global political economy as a site for colonial resource extraction (primarily cotton and crude oil), a global economic system that does not promote nor encourage the development of Chadian industrialization,[105] and the failure to support local agricultural production has meant that the majority of Chadians live in daily uncertainty and hunger.[106][107] Over 80% of Chad's population relies on subsistence farming and livestock raising for its livelihood.[38] The crops grown and the locations of herds are determined by the local climate. In the southernmost 10% of the territory lies the nation's most fertile cropland, with rich yields of sorghum and millet. In the Sahel only the hardier varieties of millet grow, and these with much lower yields than in the south. On the other hand, the Sahel is ideal pastureland for large herds of commercial cattle and for goats, sheep, donkeys and horses. The Sahara's scattered oases support only some dates and legumes.[10] Chad's cities face serious difficulties of municipal infrastructure; only 48% of urban residents have access to potable water and only 2% to basic sanitation.[40][98]

Before the development of oil industry, cotton dominated industry and the labour market accounted for approximately 80% of export earnings.[108] Cotton remains a primary export, although exact figures are not available. Rehabilitation of Cotontchad, a major cotton company weakened by a decline in world cotton prices, has been financed by France, the Netherlands, the European Union, and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). The parastatal is now expected to be privatised.[68] Other than cotton, cattle and gum arabic are dominant.[109]

According to the United Nations, Chad has been affected by a humanitarian crisis since at least 2001. As of 2008, the country of Chad hosts over 280,000 refugees from the Sudan's Darfur region, over 55,000 from the Central African Republic, as well as over 170,000 internally displaced persons.[110] In February 2008 in the aftermath of the Battle of N'Djamena, UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes expressed "extreme concern" that the crisis would have a negative effect on the ability of humanitarians to deliver life-saving assistance to half a million beneficiaries, most of whom – according to him – heavily rely on humanitarian aid for their survival.[111] UN spokesperson Maurizio Giuliano stated to The Washington Post: "If we do not manage to provide aid at sufficient levels, the humanitarian crisis might become a humanitarian catastrophe".[112] In addition, organizations such as Save the Children have suspended activities due to killings of aid workers.[113]

Infrastructure

Transport

Civil war crippled the development of transport infrastructure; in 1987, Chad had only 30 kilometres (19 mi) of paved roads. Successive road rehabilitation projects improved the network[114] to 550 kilometres (340 mi) by 2004.[115] Nevertheless, the road network is limited; roads are often unusable for several months of the year. With no railways of its own, Chad depends heavily on Cameroon's rail system for the transport of Chadian exports and imports to and from the seaport of Douala.[116]

Air transport

As of 2013 Chad had an estimated 59 airports, only 9 of which had paved runways.[117] An international airport serves the capital and provides regular nonstop flights to Paris and several African cities.

Energy

Chad's energy sector has had years of mismanagement by the parastatal Chad Water and Electric Society (STEE), which provides power for 15% of the capital's citizens and covers only 1.5% of the national population.[118] Most Chadians burn biomass fuels such as wood and animal manure for power.[119]

ExxonMobil leads a consortium of Chevron and Petronas that has invested $3.7 billion to develop oil reserves estimated at one billion barrels in southern Chad. Oil production began in 2003 with the completion of a pipeline (financed in part by the World Bank) that links the southern oilfields to terminals on the Atlantic coast of Cameroon. As a condition of its assistance, the World Bank insisted that 80% of oil revenues be spent on development projects. In January 2006 the World Bank suspended its loan programme when the Chadian government passed laws reducing this amount.[68][101] On 14 July 2006, the World Bank and Chad signed a memorandum of understanding under which the Government of Chad commits 70% of its spending to priority poverty reduction programmes.[120]

Telecommunications

The telecommunication system is basic and expensive, with fixed telephone services provided by the state telephone company SotelTchad. In 2000, there were only 14 fixed telephone lines per 10,000 inhabitants in the country, one of the lowest telephone densities in the world.[118]

Gateway Communications, a pan-African wholesale connectivity and telecommunications provider also has a presence in Chad.[121] In September 2013, Chad's Ministry for Posts and Information & Communication Technologies (PNTIC) announced that the country will be seeking a partner for fiber optic technology.

Chad is ranked last in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI) – an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. Chad ranked number 148 out of 148 overall in the 2014 NRI ranking, down from 142 in 2013.[122] In September 2010 the mobile phone penetration rate was estimated at 24.3% over a population estimate of 10.7 million.[123]

| Rank | Operator | Technology | Subscribers (in millions) | Ownership |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tigo | GSM-900 | 1.257 (Oct 2010) | MIC (100%) |

| 2 | Airtel | GSM-900 | 1.199 (June 2009) | Bharti Airtel (100%) |

| 3 | salam | GSM | 0.120 (December 2008) | Salam |

| 4 | Celtel[125] | Zain |

Media

Chad's television audience is limited to N'Djamena. The only television station is the state-owned Télé Tchad. Radio has a far greater reach, with 13 private radio stations.[126] Newspapers are limited in quantity and distribution, and circulation figures are small due to transportation costs, low literacy rates, and poverty.[79][119][127] While the constitution defends liberty of expression, the government has regularly restricted this right, and at the end of 2006 began to enact a system of prior censorship on the media.[128]

Education

Educators face considerable challenges due to the nation's dispersed population and a certain degree of reluctance on the part of parents to send their children to school. Although attendance is compulsory, only 68 percent of boys attend primary school, and more than half of the population is illiterate. Higher education is provided at the University of N'Djamena.[40][68] At 33 percent, Chad has one of the lowest literacy rates of Sub-Saharan Africa.[129]

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Labor's Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor[130] in Chad reported that school attendance of children aged 5 to 14 was as low as 39%. This can also be related to the issue of child labor as the report also stated that 53% of children aged 5 to 14 were working children, and that 30% of children aged 7 to 14 combined work and school. A more recent DOL report listed cattle herding as a major agricultural activity that employed underage children.[131]

Culture

| Date | English Name |

|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day |

| 1 May | Labour Day |

| 25 May | African Liberation Day |

| 11 August | Independence Day |

| 1 November | All Saints' Day |

| 28 November | Republic Day |

| 1 December | Freedom and Democracy Day |

| 25 December | Christmas |

Because of its great variety of peoples and languages, Chad possesses a rich cultural heritage. The Chadian government has actively promoted Chadian culture and national traditions by opening the Chad National Museum and the Chad Cultural Centre.[40] Six national holidays are observed throughout the year, and movable holidays include the Christian holiday of Easter Monday and the Muslim holidays of Eid ul-Fitr, Eid ul-Adha, and Eid Milad Nnabi.[118]

The music of Chad includes a number of instruments such as the kinde, a type of bow harp; the kakaki, a long tin horn; and the hu hu, a stringed instrument that uses calabashes as loudspeakers. Other instruments and their combinations are more linked to specific ethnic groups: the Sara prefer whistles, balafones, harps and kodjo drums; and the Kanembu combine the sounds of drums with those of flute-like instruments.[132]

Millet is the staple food of Chadian cuisine. It is used to make balls of paste that are dipped in sauces. In the north this dish is known as alysh; in the south, as biya. Fish is popular, which is generally prepared and sold either as salanga (sun-dried and lightly smoked Alestes and Hydrocynus) or as banda (smoked large fish).[133] Carcaje is a popular sweet red tea extracted from hibiscus leaves. Alcoholic beverages, though absent in the north, are popular in the south, where people drink millet beer, known as billi-billi when brewed from red millet, and as coshate when from white millet.[132]

The music group Chari Jazz formed in 1964 and initiated Chad's modern music scene. Later, more renowned groups such as African Melody and International Challal attempted to mix modernity and tradition. Popular groups such as Tibesti have clung faster to their heritage by drawing on sai, a traditional style of music from southern Chad. The people of Chad have customarily disdained modern music. However, in 1995 greater interest has developed and fostered the distribution of CDs and audio cassettes featuring Chadian artists. Piracy and a lack of legal protections for artists' rights remain problems to further development of the Chadian music industry.[132][134]

As in other Sahelian countries, literature in Chad has seen an economic, political and spiritual drought that has affected its best known writers. Chadian authors have been forced to write from exile or expatriate status and have generated literature dominated by themes of political oppression and historical discourse. Since 1962, 20 Chadian authors have written some 60 works of fiction. Among the most internationally renowned writers are Joseph Brahim Seïd, Baba Moustapha, Antoine Bangui and Koulsy Lamko. In 2003 Chad's sole literary critic, Ahmat Taboye, published his Anthologie de la littérature tchadienne to further knowledge of Chad's literature internationally and among youth and to make up for Chad's lack of publishing houses and promotional structure.[132][135][136]

The development of a Chadian film industry, which began with the short films of Edouard Sailly in the 1960s, was hampered by the devastations of civil wars and from the lack of cinemas, of which there is currently only one in the whole country (the Normandie in N'Djamena).[137][138] The Chadian feature film industry began growing again in the 1990s, with the work of directors Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, Issa Serge Coelo and Abakar Chene Massar.[139] Haroun's film Abouna was critically acclaimed, and his Daratt won the Grand Special Jury Prize at the 63rd Venice International Film Festival. The 2010 feature film A Screaming Man won the Jury Prize at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, making Haroun the first Chadian director to enter, as well as win, an award in the main Cannes competition.[140] Issa Serge Coelo directed the films, Daresalam and DP75: Tartina City.[141][142][143][144]

Football is Chad's most popular sport.[145] The country's national team is closely followed during international competitions[132] and Chadian footballers have played for French teams. Basketball and freestyle wrestling are widely practiced, the latter in a form in which the wrestlers put on traditional animal hides and cover themselves with dust.[132]

Notes

- "Analyse Thematique des Resultats Definitifs Etat et Structures de la Population". Institut National de la Statistique, des Études Économiques et Démographiques du Tchad. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Le TCHAD en bref" (in French). INSEED. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- Projections demographiques 2009–2050 Tome 1: Niveau national (PDF) (Report) (in French). INSEED. July 2014. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- DEUXIEME RECENSEMENT GENERAL DE LA POPULATION ET DE L'HABITAT (RGPH2, 2009): RESULTATS GLOBAUX DEFINITIFS (PDF) (Report) (in French). INSEED. March 2012. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "Chad". International Monetary Fund.

- "Gini Index". World Bank. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. pp. 343–346. ISBN 978-92-1-126442-5. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR90/FR90.pdf

- Decalo, pp. 44–45

- S. Collelo, Chad

- D. Lange 1988

- Decalo, p. 6

- Decalo, pp. 7–8

- "Welcome to Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Decalo, p. 53

- Decalo, pp. 8, 309

- Decalo, pp. 8–9

- Decalo, pp. 248–249

- Nolutshungu, p. 17

- "Death of a Dictator", Time, (28 April 1975). Accessed on 3 September 2007.

- Decalo, pp. 12–16

- Nolutshungu, p. 268

- Nolutshungu, p. 150

- Nolutshungu, p. 230

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002); Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3733-2, pp. 391–397

- Macedo, Stephen (2006); Universal Jurisdiction: National Courts and the Prosecution of Serious Crimes Under International Law. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1950-3, pp. 133–134

- "Chad: the Habré Legacy". Amnesty International. 16 October 2001.

- Nolutshungu, pp. 234–237

- "Chad ex-leader Habre charged in Senegal with war crimes". BBC. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- "Hissène Habré: Chad's ex-ruler convicted of crimes against humanity". BBC. 2016.

- East, Roger & Richard J. Thomas (2003); Profiles of People in Power: The World's Government Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-126-X, p. 100

- IPS, "Le pétrole au cœur des nouveaux soubresauts au Tchad"

- Chad may face genocide, UN warns. BBC News, 16 February 2007

- "Chad's leader asserts he controls". USA Today. Associated Press. 6 February 2008.

- "World Report 2011: Chad". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 6 June 2011.

- "Chad government foils coup attempt – minister". Reuters. 2013.

- Neuman, Scott (27 September 2017). "Why Is Chad on Trump's Travel Ban List?". NPR.org. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- CIA, "Chad", 2009

- "Rank Order – Area". The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency.

- "Chad". Encyclopædia Britannica. (2000)

- "Chad". Human Rights Instruments. United Nations Commission on Human Rights. 12 December 1997.

- Botha, D.J.J. (December 1992). "S.H. Frankel: Reminiscences of an Economist (Review Article)". South African Journal of Economics. 60 (4): 246–255. doi:10.1111/j.1813-6982.1992.tb01049.x.

- Kperogi, F.A. (2015) Glocal English: The Changing Face and Forms of Nigerian English in a Global World. Peter Lang, ISBN 978-1-4331-2926-1, p. 59.

- "Chad, Lake". Encyclopædia Britannica. (2000).

- Dinar, Ariel (1995); Restoring and Protecting the World's Lakes and Reservoirs. World Bank Publications. ISBN 0-8213-3321-6, p. 57

- Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568.

- (in French) Chapelle, Jean (1981) Le Peuple Tchadien: ses racines et sa vie quotidienne. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-85802-169-4, pp. 10–16

- Decalo, p. 3

- "Important Bird Areas in Africa and associated islands – Chad" (PDF). Birdlife International Organization. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- "The Flora of Chad: a checklist and brief analysis". Pensoft.net. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Plant and Animal Life". The Living Africa. Archived from the original on 28 December 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Brito, José C.; Martínez-Freiría, Fernando; Sierra, Pablo; Sillero, Neftalí; Tarroso, Pedro; Fenton, Brock (25 February 2011). "Crocodiles in the Sahara Desert: An Update of Distribution, Habitats and Population Status for Conservation Planning in Mauritania". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e14734. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...614734B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014734. PMC 3045445. PMID 21364897.

- Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723.

- "Our Africa". Our Africa organization. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Livestock-wildlife-environment interactions in Chad". Food and Agriculture Organization. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "African Elephants Slaughtered in Herds Near Chad Wildlife Park". National Geographic. 30 August 2006. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Rangers in Isolated Central Africa Uncover Grim Cost of Protecting Wildlife". The New York Times. 31 December 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ""World Population prospects – Population division"". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ""Overall total population" – World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision" (xslx). population.un.org (custom data acquired via website). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Life expectancy at birth, total (years)". October 2016. World Bank

- "Chad Livelihood Profiles" (PDF). March 2005. United States Agency for International Development.

- "COMMISSION DECISION of on the financing of a Global Plan for humanitarian operations from the budget of the European Union in CHAD" (PDF). European Commission. 2008.

- "Chad: Humanitarian Profile – 2006/2007" (PDF). 8 January 2007. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- "Chad Archived 14 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). Women of the World: Laws and Policies Affecting Their Reproductive Lives – Francophone Africa. Center for Reproductive Rights. 2000

- "Chad". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2006, 6 March 2007. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- "INSEED-TCHAD – Document". Inseed-td.net. 24 April 2018. Archived from the original on 28 December 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Haber, Marc; Mezzavilla, Massimo; Bergström, Anders; Prado-Martinez, Javier; Hallast, Pille; Saif-Ali, Riyadh; Al-Habori, Molham; Dedoussis, George; Zeggini, Eleftheria; Blue-Smith, Jason; Wells, R. Spencer; Xue, Yali; Zalloua, Pierre A.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (1 December 2016). "Chad Genetic Diversity Reveals an African History Marked by Multiple Holocene Eurasian Migrations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 99 (6): 1316–1324. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.012. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 5142112. PMID 27889059.

- "Background Note: Chad ". September 2006. United States Department of State.

- https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR90/FR90.pdf

- "Table: Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Table: Muslim Population by Country". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity" (PDF). Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. 9 August 2012. pp. 128–129. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2014.

- "Chad". International Religious Freedom Report 2006. 15 September 2006. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project: Chad. Pew Research Center. 2010.

- "Chad 1996 (rev. 2005)". Constitute. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Chad votes to end two-term limit". BBC News. 22 June 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- "Republic of Chad – Public Administration Country Profile" (PDF). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. November 2004.

- "Chad". Amnesty International Report 2006. Amnesty International Publications.

- "Chad (2006)". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2007.. Freedom of the Press: 2007 Edition. Freedom House, Inc.

- "Chad leader's victory confirmed", BBC News, 14 May 2006.

- "2012 Failed State Index". Fund for Peace. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Worst Corruption Offenders Named". BBC News. 18 October 2005.

- "Corruption Perceptions Index 2011" Transparency International.

- "Isolated Deby clings to power". BBC News. 13 April 2006. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- Djeralar Miankeol (17 June 2017). "Commercialisation is destroying community rules". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "The state of gay rights around the world". The Washington Post. 14 June 2016.

- "Chad passes law to make gay sex illegal". Gay Star News. 15 December 2016.

- (in French) "Tchad: vers le retour de la guerre? Archived 5 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine" (PDF). International Crisis Group. 1 June 2006.

- Wolfe, Adam; "Instability on the March in Sudan, Chad and Central African Republic". Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 19 June 2007., PINR, 6 December 2006.

- Manley, Andrew; "Chad's vulnerable president", BBC News, 15 March 2006.

- Human Rights Watch (2007). Early to War: Child Soldiers in the Chad Conflict. Human Rights Watch. pp. 13–.

- Reeves, Eric (9 August 2008) Victims of Genocide in Darfur: Past, Present, and Future – Sudan Tribune: Plural news and views on Sudan. Sudan Tribune. Retrieved on 28 September 2013.

- Chad rebels say to resume fight, Deby's promises unmet. Reuters. 21 March 2013

- Law, Gwillim. "Regions of Chad". Statoids. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Tableau des codes des circonscritions – Ministère de l'Intérieur", April 2008. (in French)

- "Chad". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2004, 28 February 2005. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- (in French) Ndang, Tabo Symphorien (2005) "A qui Profitent les Dépenses Sociales au Tchad? Une Analyse d'Incidence à Partir des Données d'Enquête" (PDF). 4th PEP Research Network General Meeting. Poverty and Economic Policy.

- "Chad – Community Based Integrated Ecosystem Management Project" (PDF). 24 September 2002. World Bank.

- (in French) "Tchad". L'évaluation de l'éducation pour tous à l'an 2000: Rapport des pays. UNESCO, Education for All.

- (in French) Dadnaji, Dimrangar (1999); "La decentralisation au Tchad". Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- "Chad" (PDF). African Economic Outlook 2007. OECD. May 2007. ISBN 978-92-64-02510-3

- "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "Military expenditure (% of GDP) | Data". data.worldbank.org.

- "OHADA.com: The business law portal in Africa". Retrieved 22 March 2009.

- Bush, Ray (2007). Poverty and neoliberalism: persistence and reproduction in the global south. ISBN 9780745319605.

- Amin, Samir (1990). Maldevelopment: Anatomy of a Global Failure. United Nations University Press. ISBN 9780862329310.

- Bond, Patrick (2006). Looting Africa: The Economics of Exploitation. Zed Books. ISBN 9781842778111.

- Decalo, p. 11

- "Chad economic products". NationsEncyclopedia.com. 28 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Humanitarian Action in Chad: Facts and Figures – Snapshot Report, UN, 6 March 2008

- Eastern Chad: Concerns over vital humanitarian needs (press release), UN, 7 February 2008

- Timberg, Craig (6 February 2008) Chadian Rebels Urge Cease-Fire As Push Falters, The Washington Post

- Crisis in Chad | Save the Children UK Archived 22 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Savethechildren.org.uk. Retrieved on 28 September 2013.

- "Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Development" (PDF). World Bank. 21 October 1997.

- (in French) Lettre d'information Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Délégation de la Commission Européenne au Tchad. N. 3. September 2004

- Chowdhury, Anwarul Karim & Sandagdorj Erdenbileg (2006); "Geography Against Development: A Case for Landlocked Developing Countries" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2007.. New York: United Nations. ISBN 92-1-104540-1

- "Chad". The World Factbook. CIA. 12 January 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- Spera, Vincent (8 February 2004); "Chad Country Commercial Guide – FY 2005". Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.. United States Department of Commerce.

- "Chad and Cameroon". Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 19 June 2007.. Country Analysis Briefs. January 2007. Energy Information Administration.

- World Bank (14 July 2006). World Bank, Govt. of Chad Sign Memorandum of Understanding on Poverty Reduction

- Gateway expands presence in Guinea and Senegal. IT News Africa. 22 April 2010.

- "NRI Overall Ranking 2014" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Chad Mobile Market (Q1 2008 – Q3 2010)". mnodirectory.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2011.

- Malakata, Michael (3 March 2008) Security claims blocking Africa telecom deregulation. itworldcanada.com

- Radio Stations | Embassy of the United States Ndjamena, Chad Archived 17 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Ndjamena.usembassy.gov (25 February 2013). Retrieved on 28 September 2013.

- Newspapers | Embassy of the United States Ndjamena, Chad Archived 17 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ndjamena.usembassy.gov (25 February 2013). Retrieved on 28 September 2013.

- "Chad – 2006". Freedom Press Institute.

- "50 Things You Didn't Know About Africa" (PDF). World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2013. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor – Chad". Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- "Chad: A Cultural Profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 19 June 2007. (PDF). Cultural Profiles Project. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. ISBN 0-7727-9102-3

- "Symposium on the evaluation of fishery resources in the development and management of inland fisheries". CIFA Technical Paper No. 2. FAO. 29 November – 1 December 1972.

-

- (in French) Gondjé, Laoro (2003); "La musique recherche son identité Archived 22 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine", Tchad et Culture 214.

- (in French) Malo, Nestor H. (2003); "Littérature tchadienne : Jeune mais riche Archived 28 September 2013 at Archive.today", Tchad et Culture 214.

- Boyd-Buggs, Debra & Joyce Hope Scott (1999); Camel Tracks: Critical Perspectives on Sahelian Literatures. Lawrenceville: Africa World Press. ISBN 0-86543-757-2, pp. 12, 132, 135

- Dawn – Chad's only cinema dusts off its silver screen, 9 April 2011, retrieved 8 October 2019

- The Hindu The man who brought cinema to war-hit Chad, 9 December 2017, retrieved 8 October 2019

- White, Jerry, Vertigo – Fatherlands: On Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, Africa and an Evolving Political Cinema, retrieved 8 October 2019

- Chang, Justin (23 May 2010). "'Uncle Boonmee' wins Palme d'Or". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- (in French) Bambé, Naygotimti (April 2007); "Issa Serge Coelo, cinéaste tchadien: On a encore du travail à faire Archived 30 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine", Tchad et Culture 256.

- Young, Neil (23 March 2004) An interview with Mahamet-Saleh Haroun, writer and director of Abouna ("Our Father"). jigsawlounge.co.uk

- "Mirren crowned 'queen' at Venice", BBC News, 9 September 2006.

- (in French) Alphonse, Dokalyo (2003) "Cinéma: un avenir plein d'espoir Archived 28 September 2013 at Archive.today", Tchad et Culture 214.

- Staff (2 July 2007). "Chad". FIFA, Goal Programme. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

References

- (in French) Alphonse, Dokalyo (2003); "Cinéma: un avenir plein d'espoir", Tchad et Culture 214. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Background Note: Chad". September 2006. United States Department of State.

- (in French) Bambé, Naygotimti (April 2007); "Issa Serge Coelo, cinéaste tchadien: On a encore du travail à faire", Tchad et Culture 256.

- Botha, D.J.J. (December 1992); "S.H. Frankel: Reminiscences of an Economist", The South African Journal of Economics 60 (4): 246–255.

- Boyd-Buggs, Debra & Joyce Hope Scott (1999); Camel Tracks: Critical Perspectives on Sahelian Literatures. Lawrenceville: Africa World Press. ISBN 0-86543-757-2

- Central Intelligence Agency (2009). "Chad". The World Factbook. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- "Chad". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2006, 6 March 2007. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- "Chad". Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2004, 28 February 2005. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- "Chad". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- "Chad". International Religious Freedom Report 2006. 15 September 2006. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, U.S. Department of State.

- "Amnesty International Report 2006". Amnesty International Publications.

- "Chad" (PDF). African Economic Outlook 2007. OECD. May 2007. ISBN 978-92-64-02510-3

- "Chad". The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 15 May 2007.

- "Chad" (PDF). Women of the World: Laws and Policies Affecting Their Reproductive Lives – Francophone Africa. Center for Reproductive Rights. 2000

- "Chad (2006)". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 6 May 2007.. Freedom of the Press: 2007 Edition. Freedom House, Inc.

- "Chad". Human Rights Instruments. United Nations Commission on Human Rights. 12 December 1997.

- "Chad". Encyclopædia Britannica. (2000). Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

- "Chad, Lake". Encyclopædia Britannica. (2000).

- "Chad – Community Based Integrated Ecosystem Management Project" (PDF). 24 September 2002. World Bank.

- "Chad: A Cultural Profile" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2007. (PDF). Cultural Profiles Project. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. ISBN 0-7727-9102-3

- "Chad Urban Development Project" (PDF). 21 October 2004. World Bank.

- "Chad: Humanitarian Profile – 2006/2007" (PDF). 8 January 2007. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

- "Chad Livelihood Profiles" (PDF). March 2005. United States Agency for International Development.

- "Chad Poverty Assessment: Constraints to Rural Development" (PDF). World Bank. 21 October 1997.

- "Chad (2006)". Country Report: 2006 Edition. Freedom House, Inc.

- "Chad and Cameroon". Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2007.. Country Analysis Briefs. January 2007. Energy Information Administration.

- "Chad leader's victory confirmed", BBC News, 14 May 2006.

- "Chad may face genocide, UN warns", BBC News, 16 February 2007.

- (in French) Chapelle, Jean (1981); Le Peuple Tchadien: ses racines et sa vie quotidienne. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2-85802-169-4

- Chowdhury, Anwarul Karim & Sandagdorj Erdenbileg (2006); "Geography Against Development: A Case for Landlocked Developing Countries" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2007.. New York: United Nations. ISBN 92-1-104540-1

- Collelo, Thomas (1990); Chad: A Country Study, 2d ed. Washington: U.S. GPO. ISBN 0-16-024770-5

- (in French) Dadnaji, Dimrangar (1999); "La decentralisation au Tchad". Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2007.

- Decalo, Samuel (1987). Historical Dictionary of Chad (2 ed.). Metuchen: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1937-5.

- East, Roger & Richard J. Thomas (2003); Profiles of People in Power: The World's Government Leaders. Routledge. ISBN 1-85743-126-X

- Dinar, Ariel (1995); Restoring and Protecting the World's Lakes and Reservoirs. World Bank Publications. ISBN 0-8213-3321-6

- (in French) Gondjé, Laoro (2003); "La musique recherche son identité", Tchad et Culture 214.

- "Chad: the Habré Legacy". Amnesty International. 16 October 2001.

- Lange, Dierk (1988). "The Chad region as a crossroad" (PDF), in UNESCO General History of Africa – Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century, vol. 3: 436–460. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03914-8

- (in French) Lettre d'information (PDF). Délégation de la Commission Européenne au Tchad. N. 3. September 2004.

- Macedo, Stephen (2006); Universal Jurisdiction: National Courts and the Prosecution of Serious Crimes Under International Law. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1950-3

- (in French) Malo, Nestor H. (2003); "Littérature tchadienne : Jeune mais riche", Tchad et Culture 214.

- Manley, Andrew; "Chad's vulnerable president", BBC News, 15 March 2006.

- "Mirren crowned 'queen' at Venice", BBC News, 9 September 2006.

- (in French) Ndang, Tabo Symphorien (2005); "A qui Profitent les Dépenses Sociales au Tchad? Une Analyse d'Incidence à Partir des Données d'Enquête" (PDF). 4th PEP Research Network General Meeting. Poverty and Economic Policy.

- Nolutshungu, Sam C. (1995). Limits of Anarchy: Intervention and State Formation in Chad. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1628-6.

- Pollack, Kenneth M. (2002); Arabs at War: Military Effectiveness, 1948–1991. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-3733-2

- "Rank Order – Area". The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. 10 May 2007.

- "Republic of Chad – Public Administration Country Profile" (PDF). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. November 2004.

- "Circonscriptions Administratives" (PDF) (in French). Government of Chad. 3 July 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007.

- Spera, Vincent (8 February 2004); "Chad Country Commercial Guide – FY 2005". Archived from the original on 15 October 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2007.. United States Department of Commerce.

- "Symposium on the evaluation of fishery resources in the development and management of inland fisheries". CIFA Technical Paper No. 2. FAO. 29 November – 1 December 1972.

- (in French) "Tchad". L'évaluation de l'éducation pour tous à l'an 2000: Rapport des pays. UNESCO, Education for All.

- (in French) "Tchad: vers le retour de la guerre?" (PDF). International Crisis Group. 1 June 2006.

- Wolfe, Adam; "Instability on the March in Sudan, Chad and Central African Republic". Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2007., PINR, 6 December 2006.

- World Bank (14 July 2006). World Bank, Govt. of Chad Sign Memorandum of Understanding on Poverty Reduction. Press release.

- World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision Population Database. 2006. United Nations Population Division.

- "Worst corruption offenders named", BBC News, 18 November 2005.

- Young, Neil (August 2002); An interview with Mahamet-Saleh Haroun, writer and director of Abouna ("Our Father").

External links

| Library resources about Chad |

- Chad. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Chad country study from Library of Congress

- Chad web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- Chad at Curlie

- Chad profile from the BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of Chad

Wikimedia Atlas of Chad Geographic data related to Chad at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Chad at OpenStreetMap- Key Development Forecasts for Chad from International Futures

.JPG.webp)

.svg.png.webp)