Chain migration

Chain migration is a term used by scholars to refer to the social process by which migrants from a particular town follow others from that town to a particular destination. The destination may be in another country or in a new location within the same country.

Chain migration can be defined as a “movement in which prospective migrants learn of opportunities, are provided with transportation, and have initial accommodation and employment arranged by means of primary social relationships with previous migrants.”[1] Or, more simply put: "The dynamic underlying 'chain migration' is so simple that it sounds like common sense: People are more likely to move to where people they know live, and each new immigrant makes people they know more likely to move there in turn."[2]

During the debate on immigration policy following Donald Trump's rescission of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, the use of the term "chain migration" became contentious.[3][4][5]

Chain migration in American history

Different groups of immigrants have employed chain migration among the different strategies used to enter, work, and live in the various republics of the Americas throughout their history. Social networks for migration are universal and not limited to specific nations, cultures, or crises. One group of immigrants to the British colonies in North America (and later the United States) was African slaves brought over forcibly; the circumstances of their migration do not fit the criteria of chain migration of free labor. Other groups, such as Germans fleeing chaos in Europe in the mid-1800s, Irish fleeing famine in Ireland in the same years, Eastern European Jews who emigrated from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and Italians and Japanese escaping poverty and seeking better economic conditions in the same period, did use chain migration strategies extensively, with resulting "colonies" of immigrants from the same villages, towns, and cities settling in enclaves in such cities as Boston, New York, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Toronto, Montreal, Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland and Havana from the mid-1800s through the mid-1900s.

Italian immigration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century relied on a system of both chain and return migration. Chain migration helped Italian men immigrate to such cities as New York in the United States and Buenos Aires in Argentina for work as migrant laborers. Italians generally left Italy due to dire economic conditions and returned wealthy by Italian standards after working in the Americas for a number of years. Italian immigrants were called ritorni[6] in Italy and grouped with other Southern and Eastern European migrant laborers under the term “birds of passage” in America. However, after the passage in the United States of the Immigration Act of 1924, return migration was limited and led more Italians to become naturalized citizens. The networks that had been built up by information and money due to chain and return migration provided incentives for Italian permanent migration. Mexican migration to the United States from the 1940s to the 1990s followed some of the same patterns as Italian immigration.

While immigrants to the United States from European nations during the period before the McCarran–Walter Act of 1952 were able to immigrate legally if with relative levels of ease depending on country of origin, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred almost all Chinese from immigrating to the United States. Nonetheless, many Chinese immigrants arrived in America by obtaining false documents. The Chinese Exclusion Act allowed the Chinese Americans already settled in the United States to stay and provided for limited numbers of family members of Chinese Americans to immigrate with the correct paperwork. This loophole and the fateful 1906 earthquake that destroyed San Francisco's public records provided Chinese immigrants, almost entirely men, with the potential to immigrate with false documents stating their familial relationship to a Chinese American.[7] These Chinese immigrants were called “paper sons,” because of their false papers. “Paper sons” relied on networks built by chain migration to buy documentation, develop strategies for convincing authorities on Angel Island of their legal status, and for starting a life in America.

Ethnic enclaves

The information and personal connections that lead to chain migration lead to transplanted communities from one nation to another. Throughout the history of the Americas, ethnic enclaves have been built and sustained by immigration. Different ethnic groups claimed distinct physical space in city neighborhoods to provide a reception for chain migration and maintain the community network it created. Examples of this trend include the many neighborhoods called Kleindeutschland, Little Italy, and Chinatown throughout the United States.

The same was true of rural areas in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Some rural towns in the Midwestern United States and in southern Brazil were founded by immigrants and directly advertised in home countries. (Prominent examples include New Glarus, Wisconsin in the United States and Blumenau, Santa Catarina in Brazil.) This case was especially true for many agricultural German immigrants of the nineteenth century. Certain towns were built on a homogeneous group from a particular German principality. Additionally, many of these towns exclusively spoke German until the mid-1900s in the United States and the late 1900s in Brazil. These enclaves and their contemporaries represent the close relationship between family, community, and immigration.

In the late nineteenth century, distinct Italian provinces and towns immigrated to the United States and Argentina via chain migration. Regional ties in Italy initially divided Italian ethnic identity in cities like New York and Buenos Aires, and certain enclaves included only Southern Italians or immigrants from Naples. The community ties remained strong with first generation immigrants concerning social life. These communities were originally composed of only men who immigrated for work. Once they had made enough money, many Italian men interested in settling began to bring their wives and families to their new homes in the Americas.[8]

The effects of Chinese Exclusion and discrimination prevented Chinese residents from assimilating into United States society in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Those factors, as well as social and cultural ties, precipitated the rise of Chinatowns as ethnic enclaves for Chinese Americans. Chain migration and the pseudo-familial nature of “paper sons” produced a relatively cohesive community that maintained ties with China.

Gender ratios of immigration

Single, young, male laborers were initially the largest group using chain migration to the United States in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, each immigrant group maintained a unique composition due to circumstances in home countries, goals of migration, and American immigration laws.

For example, Irish migration after 1880 had a 53.6% female majority, the only migrant group with that distinction.[9] Irish men and women faced economic crisis, overpopulation, and problematic inheritance laws for large families, thereby compelling many of Ireland's daughters to leave with its sons. Italian chain migration was initially wholly male based on intent to return, but became a source of family reunification when wives eventually immigrated.

Chinese chain migration was almost exclusively male until 1946, when the War Brides Act allowed Chinese wives of American citizens to immigrate without regard to Chinese immigration quotas. Before that time, chain migration was limited to “paper sons” and actual sons from China. The imbalanced sex ratio of Chinese immigrants was due to Chinese exclusion laws and the inability to bring current wives or to marry and return to the United States, inhibiting the corrective measure of chain migration. When immigrant groups react to economic pull factors in labor markets, chain migration via family has been used informally to balance out the gender ratio in ethnic immigrant communities.

Remittances

Remittances contribute to chain migration by aiding in both funding and interest in migration. Ralitza Dimova and Francois Charles Wolff argue that besides the recognized benefits remittances provide to the economies of the home countries of immigrants, money sent home can lead to chain migration. Dimova and Wolff posit that remittances can provide the necessary capital. H. van Dalen et al. “find that recipients of remittances are more likely to consider migrating than non-recipients. This study also references the fact that causes of chain migration through remittances tend to be variable but include such pull factors as family ties and the possibility of success.”[10]

Besides the remittances sent to families in the home country, immigrants’ letters generally included valuable information about their new life, their work, and information to guide other prospective immigrants in the family or community to ease their journey. Understanding the necessary steps, whether it is what port to leave from or who to seek out to get a job and apartment, was and is vital for successful immigration.

Advertisements

It was common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for companies and even states to advertise to potential European immigrants in their home countries.[11] These advertisements in magazines and pamphlets made information available for immigrants to find travel and decide where to settle once in the United States. Most of the advertising was done in the effort of settling the land in the Midwestern states in the wake of the Homestead Act of 1862. Consequently, many of the peoples whom this propaganda targeted were already living agricultural lives in Northern and Eastern Europe. Additionally, once the chain of migration had begun from a farm town in Europe, the pamphlets along with letters and remittances sent from America made migration an accessible opportunity for more and more of the people of that community. This chain eventually led to partial community transplantation and development of rural ethnic enclaves in the Midwest.

One example of this phenomenon is the chain migration of Czechs to Nebraska in the late nineteenth century. They were attracted by “glowing reports in Czech-language newspapers and magazines published [in Nebraska] and sent back home. Railroads, like the Burlington & Missouri Railroad, advertised large tracts of Nebraska land for sale in Czech.[12] Many similar advertisements were read in German principalities at the same time, accounting for parallel chain migration to the Great Plains. While the pull factor of these advertisements represent the potential for chain migration, and did in fact produce it, they must be understood within the context of the push factors all potential immigrants weigh when determining to leave their home country. In the case of Czech chain migration to Nebraska and many other similar circumstances in Europe, the various push factors provided the impetus to leave but the pull factors provided by pamphlets and letters provided the chain migration structure to the eventual immigration.

Legislation and chain migration

While the networks and effects of chain migration are in evidence regardless of laws limiting immigration, the changing goals and provisions of immigration legislation nonetheless affect how the system of chain migration works. Exclusion and quotas have affected who chain migration draws as potential immigrants as well as how immigrants deal with their status once in the new country. However, family reunification policies in immigration law have served to promote chain migration through extended family visas.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and its successors creating the Asiatic Barred Zone, and the National Origins quota system built by the Immigration Act of 1924 were effective in limiting chain migration but could not end it entirely. Chinese immigrants took advantage of loopholes and false documents to enter the United States until the McCarran—Walter Act of 1952 gave them a migration quota.

Other migrant groups were limited in number by the National Origins quota system, which designated national quotas based on census ratios from 1890.[13] These ratios heavily favored Western European nations and older migrant groups, such as the English, Irish, and Germans. The ratios attempted to limit the rising number of Southern and Eastern European immigrants. The National Origins quota system provided limited family reunification as a means for chain migration and placed a preference on naturalization. If an immigrant became a U.S. citizen, he or she had the ability to obtain non-quota visas for more family members, but as a resident that number was capped annually. Additionally, the Immigration Act of 1924 formally opened the door to chain migration from the entire western hemisphere, placing that group under non-quota status.

The abolition of the National Origins quota system came with the Hart–Celler Act of 1965. This legislation placed a heavy emphasis on family reunification, designating 74% of visas for that purpose. There was no limit on spouses, unmarried minor children, and parents of U.S. citizens. The percentages for family reunification were as follows: Unmarried adult children of U.S. citizens (20%), spouses and unmarried children of permanent residents aliens (20%), married children of U.S. citizens (10%), brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens over age 21 (24%).[14] These new visa preferences created a swell of new chain migration and immigration in general. The Third World began to outpace European immigration to America for the first time in history, surpassing it by the end of the 1960s and doubling the numbers of European migration by the end of the 1970s.[15]

In reaction to the flood of new immigrants brought by the Hart–Celler Act, and increasing numbers of undocumented immigrants from Mexico and Latin America, Congress attempted to reverse the consequences of the 1965 legislation by enforcing border patrol, using amnesty for undocumented immigrants in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, and proposing limits to family reunification policies. The effects of ending the Bracero Program were increased undocumented Mexican migration because of the social capital gained during that period. Chain migration had provided relatively easy access to migration for Mexicans that the immigration legislation of the 1980s to the present has attempted to deal with.

United States after 1965

In the United States, the term 'chain migration' is used by advocates of limiting immigration, to partially explain the volume and national origins of legal immigration since 1965. U.S. citizens and Lawful Permanent Residents (or "Green card" holders) may petition for visas for their immediate relatives including their children, spouses, parents, or siblings. Advocates of immigration restriction believe the family reunification policy is too permissive, leads to higher than expected levels of immigration, and what they consider the wrong type of immigrants. In its place, they favor increasing the number of immigrants with particular job skills. In practice, however, the wait times from when a family reunification petition is filed until the adult relative is able to enter the U.S. can be as long as 15–20 years (as of 2006). This is a result of backlogs in obtaining a visa number and visa number quotas that only allow 226,000 family-based visas to be issued annually.

There are four family-based preference levels, data valid as of June 2009:[16]

- Unmarried Sons and Daughters of Citizens: 23,400 plus any numbers not required for fourth preference.

- Spouses and Children, and Unmarried Sons and Daughters of Permanent Residents: 114,200, plus the number (if any) by which the worldwide family preference level exceeds 226,000, and any unused first preference numbers: A. Spouses and Children: 77% of the overall second preference limitation, of which 75% are exempt from the per-country limit; B. Unmarried Sons and Daughters (21 years of age or older): 23% of the overall second preference limitation.

- Third: Married Sons and Daughters of Citizens: 23,400, plus any numbers not required by first and second preferences.

- Fourth: Brothers and Sisters of Adult Citizens: 65,000, plus any numbers not required by first three preferences.

Backlogs in obtaining visa numbers range from four-and-a-half years (for preference level 2A) to 23-years (for preference level 4 immigrants from the Philippines).

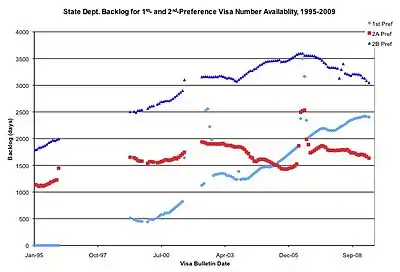

While some backlogs have remained relatively steady for some time, since 1995, backlogs for other family-sponsored preferences have steadily increased (see image to the right).

Social capital

According to James Coleman, “social capital…is created when the relations among persons change in ways that facilitate action.”[17] Douglas Massey, Jorge Durand and Nolan J. Malone assert that “each act of migration creates social capital among people to whom the migrant is related, thereby raising the odds of their migration.”[18] In the context of migration, social capital refers to relationships, forms of knowledge and skills that advance one's potential migration. One example is the positive impact of social capital on subsequent migration in China.[19] Massey et al. link their definition to Gunnar Myrdal's theory of cumulative causation of migration, stating that, “each act of migration alters the social context within which subsequent migration decisions are made, thus increasing the likelihood of additional movement. Once the number of network connections in a community reaches a critical threshold, migration becomes self-perpetuating.”[20]

See also

References

- John S. MacDonald and Leatrice D. MacDonald (1964). "Chain Migration Ethnic Neighborhood Formation and Social Networks". The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 42 (1): 82–97. doi:10.2307/3348581. JSTOR 3348581. PMID 14118225.

- Lind, Dara (29 December 2017). "What 'Chain Migration' Really Means". vox.com. Vox. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- Qiu, Linda (January 26, 2018). "The Facts Behind the Weaponized Phrase 'Chain Migration'". The New York Times.

- Levitz, Eric (January 18, 2018). "Trump's Plan to End 'Chain Migration' Is Neither Populist Nor Nationalist". Daily Intelligencer. New York Media, LLC.

- "AP style change: Two objects don't have to be in motion before they collide". Poynter. Retrieved 2018-05-07.

- Daniels, 189.

- Daniels, 246.

- Hasia Diner (2001) Hungering for America: Italian, Irish and Jewish Foodways in the Age of Migration, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 72–3, ISBN 0674034252.

- Daniels, 141.

- Ralitza Dimova and Francois Charles Wolff, “Remittances and Chain Migration: Longitudinal Evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina,” (Discussion Paper, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), March 2009), pp. 1–2.

- Strohschänk, Johannes, and William G. Thiel. The Wisconsin Office of Emigration, 1852-1855, and Its Impact on German Immigration to the State. Madison, WI: Max Kade Institute for German-American Studies, 2005.

- Homestead Act: Who Were the Settlers? The Immigrant Experience Archived 2016-03-07 at the Wayback Machine. NebraskaStudies.Org. Retrieved on 2013-07-22.

- Massey, 145.

- Massey, 216.

- Massey, 220.

- "Visa Bulletin, State Department, issue 9, volume IX". June 2009. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009.

- James S. Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 304.

- Massey, 19.

- Zhao, Yaohui (2003). "The Role of Migrant Networks in Labor Migration: The Case of China". Contemporary Economic Policy. 21 (4): 500–511. doi:10.1093/cep/byg028.

- Massey, 20.

Further reading

- Alexander, June Granatir. "Chain Migration and Patterns of Slovak Settlement in Pittsburgh Prior to World War I". Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 1, no. 1 (Fall, 1981): 56–83.

- Daniels, Roger (2002). Coming to America: A History of Immigration and Ethnicity in American Life (3rd ed.). Princeton, NJ: HarperPerennial. ISBN 978-0060505776.

- Frizzell, Robert W. "Migration Chains to Illinois: The Evidence from German-American Church Records". Journal of American Ethnic History, vol. 7, no. 1 (Fall 1987): 59–73.

- Massey, Douglas; Durand, Jorge; Malone, Nolan J. (2002). Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Era of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 978-1610443838.

- Sturino, Franc. Forging the Chain: A Case Study of Italian Migration to North America, 1880-1930. Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1990.

- Wegge, Simone A. "Chain Migration and Information Networks: Evidence from Nineteenth-Century Hesse-Cassel". The Journal of Economic History, vol. 58, no. 4 (December 1998): 957–86. doi:10.2307/2566846.