Chariot manned torpedo

The Chariot was a British manned torpedo used in World War II. The Chariot was inspired by the operations of Italian naval commandos, in particular the raid on 19 December 1941 by members of the Decima Flottiglia MAS who rode "Maiali" human torpedoes into the port of Alexandria and there placed limpet mines on or near the battleships HMS Valiant and HMS Queen Elizabeth as well as an 8,000-ton tanker, causing serious damage which put both battleships out of operational use until 1943.[1]

History

Official development of the Chariot began in April 1942, primarily led by two officers of the Royal Navy's submarine service: Commander Geoffrey Sladen DSO*, DSC and Lieutenant Commander William Richmond "Tiny" Fell CMG, CBE, DSC.[2][3] Training of crews was based out of the depot ship HMS Titania initially stationed at Gosport and later in Scotland at Loch Erisort (known as port "HZD"), Loch a' Choire (known as port "HHX") and Loch Cairnbawn (known as port "HHZ")[4] and out of HMS Bonaventure in the same region.[5]

Design and intended use

Models and specifications

Two models of the Chariot were produced:

- Chariot Mark I

Produced from 1942, thr Mark I was 6.8 m (22 feet 4 inches) long, 0.9 m (2 feet 11 inches) wide, 1.2 m (3 feet 11 inches) high, capable of a speed of 2.5 knots (4.6 km/h) and weighed 1.6 tonnes. It had a maximum diving depth of 27 m (89 ft). Its motor had three settings: slow, medium and full. Its top speed was about 3.5 knots. The motor was powered by battery which provided endurance of about seven or eight hours at 2.9 knots,[5] depending on current etc. Its control handle was shaped like . The detachable warhead contained 600 lb (270 kg) of Torpex.[4][5] Thirty-four Mk.I Chariots were made.[6]

- Chariot Mark II

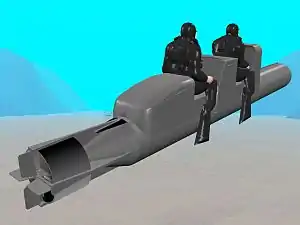

Produced from early 1944, the Mark II was 30 ft 6 in (9.3 m) long, 2 ft 6 in (0.8 m) diameter, 3 ft 3 in (1 m) maximum height, weighing 5,200 lb (2,400 kg), max speed 4.5 knots, range 5–6 hours at full speed, had two riders, who sat back to back. The Mk.II warhead contained 1,200 lb (540 kg) of explosives, twice the weight of the warhead on the Mk. I.[5] Thirty Mk.II Chariots were made.[7]

The Mk.II is easily visually distinguishable from the Mk.I in that the crew would sit fully enclosed within the hull save for their heads which would protrude.

Both types were made by Stothert & Pitt, crane makers at Bath, Somerset.

Delivery to objective

A Chariot's limited range meant that it had to be transported relatively close to its objective before its crew could ride it to the target under its own power. The warhead, which was detonated by timer, would be detached and left at the enemy ship. The crew would then attempt to ride the Chariot to a rendezvous with a friendly submarine[2][8][9] or be forced to abandon the Chariot and escape by other means.

The first attempt to use Chariots operationally was Operation Title. Two Chariots were transported to occupied Norway in October 1942 aboard a fishing vessel, the Arthur, with the objective of attacking the German battleship Tirpitz in Trondheim Fjord. In order to avoid detection by the Germans, the Chariots were towed submerged under the vessel for part of the way but both worked loose in bad weather and were lost.[4] Later deployment of the Chariot was made by carrying the machines to their point of departure by submarine. In early attempts, tubes were fitted to the deck of a submarine to contain the Chariots. The tubes were 24 feet 2 inches long and had an exterior height of 5 feet 4 inches. The Chariots sat on wheeled bogeys inside, strapped down until needed.[4] Ten tubes were built in all, three fitted to HMS Trooper, two to HMS P311 and HMS Thunderbolt and one each to HMS L23 and HMS Saracen.[4]

Later in the war, due to problems encountered with this method, Chariots were instead secured to the deck of the submarine using chocks.

Operational successes

Arguably, British operations with Chariots were not as successful as the Italians' operations had been. Nevertheless, interspersed among a number of technical equipment failures and bad luck, there were some notable successes, which are set out below.

Operation Principle: Attack on ships in Palermo and La Maddalena harbour

On 3 January 1943 a number of Chariots launched from the submarines HMS Thunderbolt and HMS Trooper attacked and sank the Italian Capitani Romani-class cruiser the Ulpio Traiano in Palermo harbour, and severely damaged the Italian troop ship, a former ocean liner, Viminale.[3]

Six charioteers were captured and two others died. Only one chariot, along with its crew, was recovered. Rod Dove received the DSO for his part in the raid.[10]

At the same time P311 was scheduled to attack targets at La Maddalena; the Italian heavy cruiser Gorizia and Trieste. P311 never returned and was presumed to have struck a mine. [11]

Operation Husky: Beach reconnaissance

Chariots were not only used for attacks on enemy vessels. In May and June 1943 reconnaissance of potential landing beaches for the allied invasion of Sicily, Operation Husky, was carried out partly by Chariots deployed from the submarines HMS Unseen and HMS Unrivalled.[12][13]

Operation QWZ: Sinking of the Bolzano

On 2 June 1944 a joint British and Italian (i.e. post-armistice) operation was mounted in order to try to prevent the German military from using the Italian cruisers Bolzano and Gorizia at La Spezia. Of two Chariots launched, one began to leak from its float tank, could not be controlled and was abandoned. The other reached the Bolzano and, with the assistance of Italian frogmen, sank the Bolzano.[3]

Ceylon Secret Operation 51: Phuket Harbour

In 28–29 October 1944 "the only completely successful British Chariot operation" occurred when two crews on Mk II Chariots, commanded by Lieutenant Tony Eldridge RNVR, were launched from the submarine HMS Trenchant (commanded by Lt.Cmdr. Arthur "Baldy" Hezlet, RN) and sank two ships in the harbour of Japanese-occupied Phuket, Thailand.[14]

See also

References

- "Manned Submarines: Italy's Daredevil Torpedo Riders". Telegraph. 20 August 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- Polmar, Norman; Allen, Thomas B. (1996). World War II: the Encyclopedia of the War Years 1941-1945. New York: Random House. p. 526. ISBN 0-486-47962-5.

- White, Michael (2015). Australian Submarines: A History. Victoria, Australia: Australian Teachers of Media. pp. 1152–1156. ISBN 978-1-876467-26-5.

- Grant, David (2006). A Submarine at War: The Brief Life of HMS Trooper. Penzance: Periscope Publishing Ltd. p. 27. ISBN 1904381332.

- "Eldridge, Anthony William Charles (Oral history)". www.iwm.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-07-24.

- O'Neill, Richard (1981). Suicide Squads: Axis and Allied Special Attack Weapons of World War II: their Development and their Missions. London: Salamander Books. pp. 296. ISBN 0 861 01098 1.

- Hobson, Robert W. Chariots of War Ulric Publishing, Church Stretton, Shropshire, England, 2004, ISBN 0-9541997-1-5. Pages 61-62

- warfarehistorynetwork.co, Manned Submarines: Italy’s Daredevil Torpedo Riders, August 26, 2015

- Human torpedo

- Sub-Lieutenant Rod Dove obituary archive link

- "Legendary wreck of British Second World War submarine found off Sardinian coast". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "HMS Unseen (P 51) of the Royal Navy - British Submarine of the U class - Allied Warships of WWII - uboat.net". 2017-07-22. Archived from the original on 2017-07-22. Retrieved 2017-07-23.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "HMS Unrivalled (P 45) of the Royal Navy - British Submarine of the U class - Allied Warships of WWII - uboat.net". uboat.net. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- As described by Lieutenant Eldridge in his account of the attack. Thompson, Julian. "The Royal Navy in the Second World War" in The Imperial War Museum Book of the War at Sea. Sidgwick & Jackson 1996. Pages 245-246.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chariot manned torpedoes. |

The Sea Our Shield, Captain W.R. Fell RN, Cassell (London: 1966)