Charles "Chaz" Bojórquez

Charles “Chaz” Bojórquez is a Chicano graffiti artist and painter who is known for his work in Cholo-style calligraphy. He is credited with bringing the Chicano and Cholo graffiti style into the established art scene.[1][2] He began his art career by tagging in his neighborhood of Highland Park, Los Angeles in the early 1970s. In his youth, Bojórquez was given the tag Chaz, which meant "the one who messes things up and likes to fight."[3]

Charles “Chaz” Bojórquez | |

|---|---|

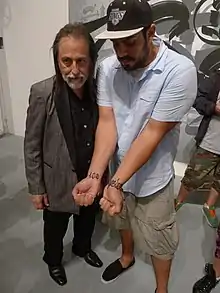

Bojórquez (left) in 2011 | |

| Born | 1949 |

Notable work | Placa/Rollcall (1980), Somos La Luz (1992) |

| Style | graffiti art |

He received formal art training at University of Guadalajara for Art, California State University, and Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles.[4] He was influenced by the Chicano art movement and the work of Gilbert "Magu" Luján.[5]

Art

Cholo-style graffiti is described as "one of the oldest forms of graffiti," which was "invented by Mexican Americans in the 1940s, when gangs marked their territories with roll-calls, or lists of names." Bojórquez and other Chicano artists were developing their own style of graffiti art known as West Coast Cholo, which was influenced by Mexican muralism and pachuco placas (tags which indicate territorial boundaries).[6]

In his 1980 work Placa/Rollcall, the piece features the placa, which "denotes territory and neighborhood loyalty, with a personal roll call of people he holds near and dear... [showing] the artistry of Chicano graffiti and resonating with traditions of abstract art and calligraphic forms from around the world."[2] In his 1992 work Somos La Luz (“we are the light"), featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, "Bojórquez created a roll-call of prominent Los Angeles graffiti artists."[4]

Identity

Bojórquez states that he experienced some resistance from his family for identifying as Chicano and also identifying the type of art he did as graffiti art. He expressed that he did not fully realize he was Chicano until he was forty years old and that it was a process of self-acceptance. Bojórquez reflected on how his identity as a Chicano and a graffiti artist were challenged by his family in an interview:

they still ask me, “Do you do graffiti? Can you change the word? You know, can you change it to ‘artistic calligraphy?’ You’re not a graffiti artist.” They hate people calling me a graffiti artist. They didn’t even like me being called a Chicano. They still don’t care too much for it. Because for them, it was a bad word, and it wasn’t going to go anywhere. It was a detriment to an art career. My mom felt to be a real artist, you had to be in a museum. She said, “You got a shot at it, and you should drop that ‘Chicano’ and that graffiti stuff. You have skill.” I go, “Mom, having skills is not enough.”[1]

References

- Bojorquez, Charles "Chaz" (2007). "Interview with Charles Chaz Bojorquez" (PDF). CSRC Oral Histories Series. 5: 1–9.

I think you can say if there is a definition for Chicano,what it is, I qualify... I did not become a Chicano until I was forty. I had to find that. You know you’re not born a Chicano.

- "Placa/Rollcall". Smithsonian American Art Museum. 2013.

- K., Dea (20 March 2017). "Charles Bojórquez". Widewalls.

- "Somos La Luz". Smithsonian American Art Museum. 2013.

- Bojorquez, Charles "Chaz" (2007). "Interview with Charles Chaz Bojorquez" (PDF). CSRC Oral Histories Series. 5: 49.

But I started seeing the Chicano art movement at that time. And that made more sense to me, and it was something I never had seen before. And I was really inspired by Magu.

- Tatum, Charles M. (2017). Chicano Popular Culture, Second Edition: Que Hable el Pueblo. University of Arizona Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780816536528.