Charlie Haden

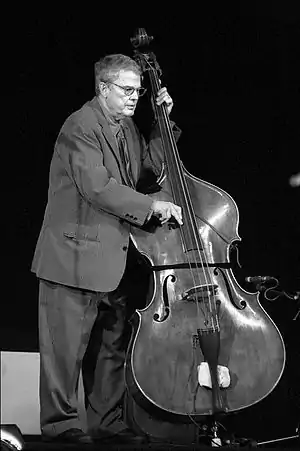

Charles Edward Haden (August 6, 1937 – July 11, 2014) was an American jazz double bass player, bandleader, composer and educator whose career spanned more than 50 years. In the late 1950s, he was an original member of the ground-breaking Ornette Coleman Quartet.

Charlie Haden | |

|---|---|

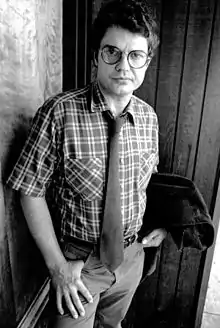

Haden in 1981 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Charles Edward Haden |

| Born | August 6, 1937 Shenandoah, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | July 11, 2014 (aged 76) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, composer, bandleader, educator |

| Instruments | Double bass |

| Years active | 1957–2014 |

| Associated acts | |

| Website | charliehadenmusic |

Haden revolutionized the harmonic concept of bass playing in jazz. German musicologist Joachim-Ernst Berendt wrote that Haden's "ability to create serendipitous harmonies by improvising melodic responses to Coleman's free-form solos (rather than sticking to predetermined harmonies) was both radical and mesmerizing. His virtuosity lies…in an incredible ability to make the double bass 'sound out'. Haden cultivated the instrument's gravity as no one else in jazz. He is a master of simplicity which is one of the most difficult things to achieve." [1] Haden played a vital role in this revolutionary new approach, evolving a way of playing that sometimes complemented the soloist and sometimes moved independently. In this respect, as did his predecessor bassists Jimmy Blanton and Charles Mingus, Haden helped liberate the bassist from a strictly accompanying role to becoming a more direct participant in group improvisation. In 1969, he formed his first band, the Liberation Music Orchestra, featuring arrangements by pianist Carla Bley. In the late 1960s, he became a member of pianist Keith Jarrett's trio, quartet and quintet. In the 1980s, he formed his band, Quartet West. Haden also often recorded and performed in a duo setting, with musicians including guitarist Pat Metheny and pianist Hank Jones.

Biography

Early life

Haden was born in Shenandoah, Iowa.[2] His family was exceptionally musical and performed on the radio as the Haden Family, playing country music and American folk songs.[3] Haden made his professional debut as a singer on the Haden Family's radio show when he was just two years old. He continued singing with his family until he was 15 when he contracted a bulbar (brainstem) form of polio affecting his throat and facial muscles.[2] At the age of 14, Haden had become interested in jazz after hearing Charlie Parker and Stan Kenton in concert. Once he recovered from his bout with polio, Haden began in earnest to concentrate on playing the bass. Haden's interest in the instrument was not sparked by jazz bass alone, but also by the harmonies and chords he heard in compositions by Bach.[4] Haden soon set his sights on moving to Los Angeles to pursue his dream of becoming a jazz musician, and to save money for the trip, took a job as house bassist for ABC-TV's Ozark Jubilee in Springfield, Missouri.

Early career

Haden often said that he moved to Los Angeles in 1957 in search of pianist Hampton Hawes.[5] He turned down a full scholarship at Oberlin College, which did not have an established jazz program at the time, to attend Westlake College of Music in Los Angeles.[6] His first recordings were made that year with Paul Bley, with whom he worked until 1959. He also played with Art Pepper for four weeks in 1957, and from 1958 to 1959, with Hampton Hawes whom he met through his friendship with bassist Red Mitchell,[3] For a time, he shared an apartment with the bassist Scott LaFaro.

In May 1959, he recorded his first album with the Ornette Coleman Quartet, the seminal The Shape of Jazz to Come.[2] Haden's folk-influenced style complemented Coleman's microtonal, Texas blues elements. Later that year, the Quartet moved to New York City and secured an extended booking at the avant-garde Five Spot Café.[5] This residency lasted six weeks and represented the beginnings of their unique, free and avant-garde jazz. Ornette's quartet played everything by ear, as Haden explained: “At first when we were playing and improvising, we kind of followed the pattern of the song, sometimes. Then, when we got to New York, Ornette wasn’t playing on the song patterns, like the bridge and the interlude and stuff like that. He would just play. And that's when I started just following him and playing the chord changes that he was playing: on-the-spot new chord structures made up according to how he felt at any given moment.”[6]

In 1960, drug problems caused him to leave Coleman's band. He went to self-help rehabilitation in September 1963 at Synanon houses in Santa Monica, California and San Francisco, California. It was during the time he was at Synanon House that he met his first wife, Ellen David. They moved to New York City's Upper West Side where their four children were born: their son, Josh, in 1968, and in 1971, their triplet daughters Petra, Rachel and Tanya. They separated in 1975 and subsequently divorced.

1964 to 1984

Haden resumed his career in 1964, working with saxophonist John Handy and pianist Denny Zeitlin's trio, and performing with Archie Shepp in California and Europe. He also did freelance work from 1966 to 1967, playing with Henry “Red” Allen, Pee Wee Russell, Attila Zoller, Bobby Timmons, Tony Scott, and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra. He recorded with Roswell Rudd in 1966, and returned to Coleman's group in 1967. This group remained active until the early 1970s. Haden was known for being able to skillfully follow the shifting directions and modulations of Ornette's improvised lines.[3]

Haden became a member of Keith Jarrett's trio and his 'American Quartet' from 1967 to 1976 with drummer Paul Motian and saxophonist Dewey Redman.[2] The group also included percussionist Guilherme Franco.[5] He also organized the collective Old and New Dreams, which consisted of Don Cherry, Redman, and Ed Blackwell, who had been members of Coleman's band. These musicians understood, and could independently express and honor Coleman's improvisational concepts, applying it to their performances with this band. They continued to play Coleman's music in addition to their own original compositions.[7] In 1970 Haden received a Guggenheim Fellowship for Music Composition upon the recommendation of the eminent conductor Leonard Bernstein. Over the years, Haden received several NEA grants for composition. Haden founded his first band, the Liberation Music Orchestra ("LMO") in 1969, working with arranger Carla Bley, Paul Bley's ex-wife. Their music was very experimental, exploring both the realms of free jazz and political music. The first album focused specifically on music from the Spanish Civil War which had markedly inspired Haden. Also inspired by the turbulent 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, he superimposed songs such as "You're a Grand Old Flag" and "Happy Days are Here Again", contrasted with "We Shall Overcome".

The original lineup consisted of Haden and Carla Bley, Gato Barbieri, Redman, Motian, Don Cherry, Andrew Cyrille, Mike Mantler, Roswell Rudd, Bob Northern, Howard Johnson (tuba and bass saxophone), Perry Robinson, and Sam Brown.

Over the years, the LMO had a shifting membership comprising a "who's who" of jazz instrumentalists, and consisted of twelve members from multicultural backgrounds.[8] Its members also included Ahnee Sharon Freeman and Vincent Chancey (French horn), Tony Malaby (tenor saxophonist) Joseph Daley (tuba), Seneca Black (trumpet), Michael Rodriguez (trumpet), Miguel Zenón (alto saxophone), Chris Cheek (tenor saxophone), Curtis Fowlkes (trombone), Steve Cardenas (guitar), and Matt Wilson (drums).[5] Through Bley's arranging, they employed not only more common trombone, trumpet and reeds but included the tuba and French horn. The group won multiple awards in 1970, including France's Grand Prix du Disque from the Académie Charles Cros, and Japan's Gold Disc Award from Swing Journal.[7]

In 1971, while on tour with the Ornette Coleman Quartet in Portugal (at the time under a fascist dictatorship), Haden dedicated a performance of his "Song for Che" to the anticolonialist revolutionaries in the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique, Angola, and Guinea. The following day, he was detained at Lisbon Airport, jailed, and interrogated by the DGS, the Portuguese secret police. He was only released after Ornette Coleman and others complained to the American cultural attaché, and he was later interviewed in the United States by the FBI about his choice of dedication.[9]

Haden decided to form the LMO at the height of the Vietnam War, out of his frustration that so much of the government's energy was spent on the war (in which there were many fatalities), while so many internal problems in the United States (such as poverty, civil rights, mental illness, drug addiction, and unemployment), were neglected. Haden's goal was to use the LMO to amplify unheard voices of oppressed people. He wanted to express his solidarity with progressive political movements from around the world by performing music that made a statement about how to initiate and celebrate liberating change. The LMO's 1982 album The Ballad of the Fallen on ECM commented again on the Spanish Civil War as well as the United States involvement in Latin America. The LMO toured extensively throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[8] In 1990, the orchestra returned with Dream Keeper, inspired by a poem of Langston Hughes, and which also drew on American gospel music and South African music to comment on racism in the US and apartheid in South Africa. The album featured choral contributions from the Oakland Youth Chorus. In 2005, Haden released the fourth Liberation Music Orchestra album Not in Our Name, a protest against the US invasion and occupation of Iraq.

In 1982, Haden established the Jazz Studies Program at California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California. His program emphasized smaller group performance and the spiritual connection to the creative process. He encouraged students to discover their individual sounds, melodies, and harmonies. Haden was honored by the Los Angeles Jazz Society as "Jazz Educator of the Year" for his educational work in this program.[7] Haden's students included John Coltrane's son, tenor saxophonist Ravi Coltrane, trumpeter Ralph Alessi, pianist and composer James Carney and bassist Scott Colley.[4][10]

1984–2000

In 1984, Haden met the singer and former actress Ruth Cameron. They married in New York City, and throughout their marriage, Ruth managed Haden's career as well as co-producing many albums and projects with him.

In 1986, Haden formed his band Quartet West at Ruth's suggestion. The original quartet consisted of Ernie Watts on sax, Alan Broadbent on piano, and long-time collaborator Billy Higgins on drums. Higgins was later replaced by Larance Marable. When Marable became too ill to perform, drummer Rodney Green was added to the band. In addition to original compositions by Haden and Broadbent, their repertoire also included 1940s pop ballads which they played a noir-infused, bop-oriented style.[5] A brief collaboration with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson and drummer Al Foster showcased Haden's playing in a more hard-driving jazz context.

In 1989, Haden inaugurated the "Invitation" series at the Montreal Jazz Festival. With different musicians he selected, they performed in concert for eight consecutive nights of the festival. Each of these events was recorded, and most have been released in the series, The Montreal Tapes.

In 1994, Ginger Baker, legendary drummer from the band Cream, formed another trio called The Ginger Baker Trio with Haden and guitarist Bill Frisell.

Duets: Haden performing in duets as he loved the intimacy the format provided. In 1995, Haden released Steal Away: Spirituals, Hymns and Folk Songs with pianist Hank Jones, an album based on traditional spirituals and folk songs. Haden both played on and produced the album.[11] In late 1996, he collaborated with guitarist Pat Metheny on the album Beyond the Missouri Sky (Short Stories), exploring the music that influenced them in their childhood experiences in, respectively southwest Iowa and northwest Missouri, with what Haden called "contemporary impressionistic Americana". Haden was awarded his first Grammy award for the album, for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance.[12]

In 1997, classical composer Gavin Bryars wrote By the Vaar, an extended adagio for Haden. Instrumentation included strings, bass clarinet and percussion. The piece was recorded with the English Chamber Orchestra, on the album Farewell to Philosophy. It is a synthesis of jazz and classical chamber music, featuring resonant pizzicato notes and gut strings in imitation of Haden's bass sound.[7]

2000–2014

In 2001, Haden won the Latin Grammy Award for Best Latin Jazz CD for his album Nocturne which contains boleros from Cuba and Mexico. In 2003, he won the Latin Grammy Award for Best Latin Jazz Performance for his album Land of the Sun.[7] Haden reconvened the Liberation Music Orchestra in 2005, with largely new members, for the album Not In Our Name, released on Verve Records. The album dealt primarily with the contemporary political situation in the United States.

In 2008, Haden co-produced, with his wife Ruth Cameron Haden, the album Charlie Haden Family and Friends: Rambling Boy. It features several members of his immediate family, including Ruth Cameron, his musician triplets, son Josh, and Tanya's husband, singer and multi-instrumentalist Jack Black. They were joined by banjoist Béla Fleck, and guitarist/singers Vince Gill, Pat Metheny, Elvis Costello, Rosanne Cash, Bruce Hornsby (piano and keyboards), among other top Nashville musicians.[7] The album harkens back to Haden's days of playing Americana and bluegrass music with his parents on their radio show. The idea came to Haden when his wife Ruth gathered the Haden family together for his mother's 80th birthday and suggested they all sing "You Are My Sunshine" in the living room, as that was a song everyone knew.[13] Rambling Boy was intended to connect music from his early childhood in the Haden Family band to the new generation of the Haden family as well. The album includes songs made famous by the Stanley Brothers, the Carter Family, and Hank Williams, in addition to traditional songs and original compositions.

In 2009, Swiss film director Reto Caduff released a film about Haden's life, titled Rambling Boy. It screened at the Telluride Film Festival and at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2009. In the summer of 2009, Haden performed again with Coleman at the Meltdown Festival in Southbank, London. He also performed and produced duet recordings with pianist Kenny Barron, with whom he recorded the album Night and the City. In February 2010, Haden and pianist Hank Jones recorded a companion to Steal Away: Spirituals, Hymns and Folk Songs called Come Sunday. Jones died three months after the recording of the album.[7]

Awards: In 2012, Haden was a recipient of the NEA Jazz Masters Award. In 2013, Haden received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2014, Haden was bestowed the Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture. A posthumous ceremony in his honor took place at the French Cultural Services in January 2015, in NYC where his wife Ruth was presented with the medal.

Posthumous releases: In September 2014, three months after his death, the newly reactivated Impulse! label released Charlie Haden-Jim Hall, a recording of a duo performance at the 1990 Montreal International Jazz Festival. "This album documents a rarified journey", wrote pianist Ethan Iverson in the album's liner notes. Although terminally ill, Haden produced and worked on the album. In June 2015, Impulse released Tokyo Adagio, a 2005 collaboration with Gonzalo Rubalcaba, similarly produced by Haden when he was near death.[14]

Legacy

Spirituality and teaching method

While he did not identify himself with a specific religious orientation, Haden was interested in spirituality, especially in association with music. He felt it was his duty, and the duty of the artist, to bring beauty to the world, to make this world a better place. He encouraged his students to find their own unique musical voice and bring it to their instrument. He also encouraged his students to be in the present moment: "there's no yesterday or tomorrow, there's only right now", he explained.[8] In order to find this state, and ultimately to find one's spiritual self, Haden urged one to aspire to have humility, and respect for beauty; to be thankful for the ability to make music, and to give back to the world with the music they create. He claimed that music taught him this process of exchange, so he taught it to his students in return.[8] Music, Haden believed, also teaches incredibly valuable lessons about life: "I learned at a very young age that music teaches you about life. When you're in the midst of improvisation, there is no yesterday and no tomorrow—there is just the moment that you are in. In that beautiful moment, you experience your true insignificance to the rest of the universe. It is then, and only then, that you can experience your true significance."[13]

Musical philosophy

Haden also viewed jazz as the "music of rebellion" and felt it was his responsibility and mission to challenge the world through music, and through artistic risks that expressed his own individual artistic vision. He believed that all music originates from the same place, and because of this, he resisted the tendency to divide music into categories. He was democratic in his tastes and musical partners, and was interested in musical collaboration with individuals who shared his sensibilities in music and life.[8] His music (specifically the music he created with the LMO), was based on the music of peoples struggling for freedom from oppression. Haden spoke to this in reference to his 2002 album American Dreams, stating: “I always dreamed of a world without cruelty and greed, of a humanity with the same creative brilliance of our solar system, of an America worthy of the dreams of Martin Luther King, and the majesty of the Statue of Liberty...This music is dedicated to those who still dream of a society with compassion, deep creative intelligence, and a respect for the preciousness of life—for our children, and for our future.”[5]

Musical style

In addition to his lyrical playing, Haden was known for his warm tone and subtle vibrato on the double bass. His approach to the bass stemmed from his belief that the bassist should move from an accompanying role to a more direct role in group improvisation. This is particularly clear in his work with the Ornette Coleman Quartet where he frequently improvised melodic responses to Coleman's free-form solos instead of playing previously written lines.[3] He frequently closed his eyes while performing, and assumed a posture in which he bent himself around the bass until his head was almost at the bottom of the bridge of the bass.[8]

In an interview with Haden, pianist Ethan Iverson noted that Haden's "combination of folk song, avant-garde sensibility, and Bach-like classical harmony is a stream in this music just as distinctive as Thelonious Monk or Elvin Jones."[15]

Haden owned one three-quarters-sized bass, and one seven-eighths-sized bass. The larger bass is one of a small number of basses made by Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, a French luthier, in the mid-nineteenth century. He greatly valued this bass, playing it only at recording sessions and jobs in close proximity to his home so as not to risk damaging it in transit. He attributed the bass's special and valuable nature to the varnish used by Vuillaume, which is similar to Italian varnish.[4]

Haden suffered from tinnitus, a ringing in both ears that he believed he acquired from constant exposure to playing in proximity to drums, and possibly from an extremely loud concert in which he played during the late 1960s. He also suffered from hyperacusis, or sensitivity to loud noises. As a result, when he played with a drummer, he had to play behind a Plexiglass divider.[4]

"American Quartet" pianist Keith Jarrett said of Charlie's way of playing, "He wanted to relate to the material in a very personal style all the time. He wasn't somebody to get into a groove and just enjoy it simply because it was a groove".

Personal life

Haden died in Los Angeles on July 11, 2014, at the age of 76. He had been suffering from effects of post-polio syndrome and complications from liver disease.[16][17][18] His wife, Ruth, and his four children were by his side.

A memorial concert was held in New York City's Town Hall on January 13, 2015, produced and organized by Ruth, where his fellow musicians, family members, friends and fans remembered and celebrated his life.[19]

Haden was survived by his wife Ruth and his four children from his first marriage. His son, Josh Haden, is a bass guitarist and singer of the group Spain. His daughters, Petra, Tanya and Rachel Haden, are all singers and instrumentalists. Petra plays the violin, Rachel, the piano and bass guitar, and Tanya, a visual artist, plays the cello. They have a band called The Haden Triplets and recorded their self-titled album in 2012. Comedian/actor Jack Black was his son-in-law via Tanya.

Material loss

On June 25, 2019, The New York Times Magazine listed Charlie Haden among hundreds of artists who had master recordings that were likely destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[20]

Discography

|

|

|

References

- Joachim Berendt, The Jazz Book

- allmusic Biography

- Kernfeld, Barry. "Haden, Charlie". Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Davis, Francis (August 2000). "Charlie Haden, Bass". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- "Biography". Verve Music. Archived from the original on September 1, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Heckman, Don (April 19, 2011). "Charlie Haden: Everything Man". Jazz Times. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- "Charlie Haden Official Website". Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Connor, Kimberly Rae (2000). Imagining Grace. Illinois, USA: University of Illinois Press. pp. 239–292.

- Jazz Legend Charlie Haden on His Life, His Music and His Politics. Democracy Now. September 1, 2006 Accessed January 5, 2009.

- "Red Cat" (PDF). Red Cat.

- Giddins, Gary (1998). Visions of Jazz: The First Century. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 19–23.

- "Past Winners Search". GRAMMY.com. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- "Charlie Haden Returns To His Bluegrass Roots". NPR. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Charlie Haden and Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Tokyo Adagio, Pop Matters, Jedd Beaudoin, August 11, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- Ethan Iverson (March 2008). "Interview with Charlie Haden". Do The Math. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- Peter Hum, "RIP, Charlie Haden", Ottawa Citizen, July 12, 2014.

- Marc Myers, "Giving the Bass a Voice", Wall Street Journal, July 14, 2014.

- Marc Myers, "Charlie Haden (1937-2014)" Archived July 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, JazzWax, July 15, 2014.

- Ratliff, Ben (January 14, 2015). "Jazz Musicians Memorialize Charlie Haden". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 9, 2016.

- Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). "Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charlie Haden. |

- Heffley. "Haden, Charlie". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press

- Charlie Haden Official Web site

- Charlie Haden interview on Democracy Now!, September 1, 2006

- Official documentary website

- Charlie Haden at IMDb

- DTM Interview

- Charlie Haden Discography, All About Jazz

- NPR interview