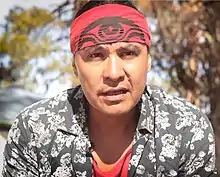

Chase Iron Eyes

Chase Iron Eyes (born March 6, 1978)[2][3] is an American Indian activist, attorney, politician, and a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe. He is a member of the Lakota People's Law Project and a co-founder of the Native American news website Last Real Indians.[4] In April 2016 he announced his candidacy for the United States House of Representatives for North Dakota's at-large congressional district. He lost to incumbent Kevin Cramer.

Chase Iron Eyes | |

|---|---|

Chase Iron Eyes speaks in 2017 | |

| Born | Chase A. Iron Eyes March 6, 1978 |

| Nationality | United States |

| Education | |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 2011–present |

| Organization | Lakota People's Law Project |

| Spouse(s) | Dr. Sara Jumping Eagle[1] |

| Children | 3, including Tokata Iron Eyes[1] |

| Website | Last Real Indians |

Personal life

Iron Eyes was raised on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, since then has lived in a multitude of places.

Chase is an enrolled member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe.

Career

Iron Eyes graduated from the University of North Dakota with a bachelor's degree in political science and American Indian studies.[5] In 2007, he graduated from the University of Denver Sturm College of Law, with a Juris Doctor in law (with an emphasis in Federal Indian law).[6] Iron Eyes was also the president of the Native American Law Student Association during his academic career in law school.[7] Iron Eyes is licensed to practice law within the state of South Dakota as well as in the federal courts of both North Dakota and South Dakota[5] in addition to several tribal court systems.[8]

In July 2012, Iron Eyes filed a civil suit in federal court on behalf of Vern Traversie, a blind 69-year-old Lakota man, against a South Dakota hospital. The lawsuit alleged a violation of Traversie's civil rights, citing scars that Traversie said were from doctors carving the initials of the Ku Klux Klan into his abdomen during heart surgery.[9] The hospital stated the marks were a reaction to surgical tape, and in 2015, a jury ruled against Traversie.[10]

Activism

Iron Eyes has used his career as an attorney to advocate for Native American civil rights. He has served as a staff attorney for the Lakota People's Law Project (LPLP),[11] an initiative founded in 2005 with the purpose of ending the unlawful practice of removing Lakota children from their families and placing them in foster care outside their communities.[12] In the summer of 2016, Iron Eyes and other representatives of LPLP joined with other anti-pipeline protestors near Standing Rock to resist the Dakota Access pipeline.

Iron Eyes has actively engaged in the protection of sacred sites. He was instrumental in raising awareness of Pe' Sla,[13] a high mountain prairie situated within the heart of the Black Hills, a sacred site related to Lakota creation beliefs where annual ceremonies, village gatherings, and other traditional activities took place, located north of Deerfield Lake and west of Black Elk Peak. This is the area where renowned Lakota visionary Black Elk sought his vision.[14] Another of the sacred sites Iron Eyes has drawn attention to is Bear Butte.[5]

He is also a member of the Bush Foundation's Native Nation Rebuilders program, a leadership development program designed to foster innovative tribal governance practices to effect positive change.[15] He has continued to voice opposition against the drilling of oil wells within the area.[16]

In 2016, Iron Eyes announced his candidacy as a member of the Democratic Party for the election to represent North Dakota's at-large congressional district in the United States House of Representatives.[17] Speaking to Prairie Public Radio in April, he said, "I'm running for Congress out of necessity [...] I see that our government is broken, and I feel responsible to do my part to try and fix this on behalf of North Dakota", as reported by Indian Country Today Media Network.[18]

Filmography

| Film | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Film | Role | Notes |

| 2014 | Mitakeoyashin | Himself | Documentary |

References

- "Our Team". Lakota People's Law Project. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- Meet the Native American candidate the oil industry doesn’t want in Congress

- United States Public Records, 1970-2009 (North Dakota, 2005-2008)

- Saint Thomas, Sophie (March 22, 2015). "Let Them Tell Their Story: An Interview with Chase Iron Eyes, Co-Founder of 'Last Real Indians'". Vice. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "Chase Iron Eyes". Intercontinental Cry. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- "Chase Iron Eyes". LinkedIn. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- "Bush Foundation Announces Fourth Cohort of Native Nation Rebuilders". Minnesota Council on Foundations. November 28, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- "Chase Iron Eyes". LRInspire. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- Glionna, John M. (July 17, 2012). "Doctors carved 'KKK' into Lakota man's skin, lawsuit claims". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "Jury rules against Cheyenne River man". Lakota Country Times. April 2, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Sullivan, Laura (August 29, 2014). "Justice Department Supports Native Americans In Child Welfare Case". NPR. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "They come for the young ones". Lakota Law People's Project. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- Rose, Christina (December 21, 2012). "Pe' Sla Purchase Guarantees Sacred Land Will Be Used for Ceremonies". Indian Country Today Media Network. Retrieved September 15, 2016.

- "The Black Hills - America's Sacred Site". Geometry of Place. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "Chase Iron Eyes". Bush Foundation. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "SD commission cuts number of wells allowed at oil field near Bear Butte". Protect Bear Butte. May 19, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2015.

- "2016 Primary Election Contest/Candidate List". vip.sos.nd.gov. North Dakota Secretary of State. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- Trahant, Mark (April 3, 2016). "Chase Iron Eyes Runs In North Dakota Out of 'Necessity'". Indian Country Today Media Network.