Chasseur (1812 clipper)

Chasseur was a Baltimore Clipper commanded by Captains Pearl Durkee (February 1813), William Wade (1813) and Thomas Boyle (1814-1815).[1] She was one of the best equipped and manned American privateers during the War of 1812.[2]

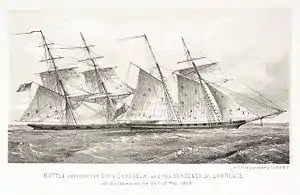

Chasseur capturing HMS St Lawrence, by Adam Weingartner | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Chasseur |

| Builder: | Thomas Kemp |

| Launched: | 12 December 1812 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Baltimore Clipper/Privateer |

| Tons burthen: | 356 (bm) |

| Length: | 115 ft 6 in (35.2 m) |

| Beam: | 26 ft 8 in (8.1 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 12 ft 9 in (3.9 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sail |

| Sail plan: | Topsail schooner |

| Complement: | 160 |

| Armament: | 16 × 12-pounder guns |

Merchant Vessel Career

Thomas Kemp built Chasseur at Fell's Point in Baltimore as a topsail schooner. He built her a merchant vessel for William Hollins, but also owned a share in her. Kemp launched her on 12 December 1812.[3][4][5]

The British blockade of the Chesapeake Bay during the War of 1812 impeded her merchant career. The Royal Navy had placed Chesapeake Bay under a strict blockade in March 1813, though that declaration became known as a "paper blockade" as some 50 to 60 American privateers were rather freely cruising the coast and the waters of the West Indies.[6]

Her owners decided to enter the popular business of privateering instead. She was granted a letter of marque on 23 February 1813 and started her career of a privateer.

Career as Privateer during the War of 1812

First West Indies Cruise

Chasseur, under Captain William Wade's command, evaded the blockade and cruised the West Indies from July until the Christmas of 1813, harassing the British merchant fleet.[6] Chasseur captured at least six British vessels and burned five of them after divesting them of their valuables. Some sources record the capture of as many as eleven prizes during this cruise.[1][5]

1814 European cruise

In July 1814, Captain Thomas Boyle took command of Chasseur. He sailed across the Atlantic ocean and harassed British merchant shipping from the coasts of Portugal and Spain to the English and Irish channels.

Most famously, while cruising the English channel, Boyle had proclaimed a blockade on the entire United Kingdom to show the absurdity of "paper blockades". Boyle's proclamation was posted in Lloyd's Coffee House in London:[2]

PROCLAMATION:

Whereas, It has become customary with the admirals of Great Britain, commanding small forces on the coast of the United States, particularly with Sir John Borlase Warren and Sir Alexander Cochrane, to declare all the coast of the said United States in a state of strict and rigorous blockade without possessing the power to justify such a declaration or stationing an adequate force to maintain said blockade;

I do therefore, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested (possessing sufficient force), declare all the ports, harbors, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, and seacoast of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in a state of strict and rigorous blockade.

And I do further declare that I consider the force under my command adequate to maintain strictly, rigorously, and effectually the said blockade.

And I do hereby require the respective officers, whether captains, commanders, or commanding officers, under my command, employed or to be employed, on the coasts of England, Ireland, and Scotland, to pay strict attention to the execution of this my proclamation.

And I do hereby caution and forbid the ships and vessels of all and every nation in amity and peace with the United States from entering or attempting to enter, or from coming or attempting to come out of, any of the said ports, harbors, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, or seacoast under any pretense whatsoever. And that no person may plead ignorance of this, my proclamation, I have ordered the same to be made public in England.

Given under my hand on board the Chasseur.

THOMAS BOYLE

By command of the commanding officer.

J. J. STANBURY, Secretary.

This affront and five days of actual blockage of St. Vincent sent the shipping community into panic and caused them to send a letter to Admiral Durham, who dispatched the frigate HMS Barrosa to chase Chasseur. Later the Admiralty called vessels home from the American war to guard merchant ships, which had to sail in convoys.[2]

Chasseur returned from her famous 3-month European cruise to New York on 24 or 29 October 1814. George R. Roberts was a gunner of the schooner.

Second West Indies Cruise and Capture of HMS St Lawrence

In the winter of 1814 and 1815 Chasseur returned to the West Indies. On February 26, 1815, just off Havana, Chasseur met an unidentified ship, which was the English, but American-built, schooner HMS St Lawrence. Chasseur fired a gun and showed her colors while still about three miles away; when the other ship did not show her colours Chasseur started the chase. She carried 14 guns and 102 men, while St Lawrence carried 13 guns and 75 men,[2] including officers, soldiers, and civilians bound to the British squadron off New Orleans. At about 1:26pm, when the schooners were close to each other, St Lawrence revealed her armament and uniformed sailors and opened fire, catching Chasseur off guard. Chasseur was able to close St Lawrence and a number of Americans, led by the prize master N. W. Christie, jumped aboard St Lawrence. The intense action that followed lasted only about 15 minutes during which St Lawrence suffered six men killed and 17 wounded, several of them mortally. (According to American accounts, the English had 15 killed and 25 wounded.) Chasseur had five killed and eight wounded; Boyle was among the wounded.[2] Both vessels were badly damaged. Captain Boyle made a cartel of St Lawrence and sent her and her crew into Havana as his prize.[6]

Impact

During the cruise to the British Isles and the winter of 1814/1815 Chasseur captured eighteen valuable merchant ships, carrying wine, brandy, dry goods, cotton, cocoa, etc.[6] Nine of those ships were sent to the United States. One source estimated a total damage to the Royal Navy from Chasseur's 1813-1815 activities at one and a half million dollars.[6] The captured goods from Carlebury alone were valued at $50,000.[2][7] However, it is important to notice that the Royal Navy recaptured many of the Chasseur's prizes, making it harder to estimate the actual loss to British commerce.

Prizes

List of some of the prizes that Chasseur captured during the War of 1812:[8]

- Adventure, ship, divested off cargo, sent to Charleston, South Carolina, but recaptured there

- Alert, brig, divested and burned

- American, schooner, divested and burned

- Ann Maria, schooner, divested and burned

- Britannia, brig, sent to Beaufort

- Carlebury, ship, valued at $50,000, ordered in

- Christianna of Scotland, sloop

- Commerce, brig, sent to Charleston, South Carolina

- Eclipse, brig, bound to Liverpool from Buenos Aires, captured and sent it to New York.[8]

- Favorite, sloop, divested and burned

- Joanna of Malta, divested and burned

- Harmony, brig, converted into a cartel

- Martha, sloop, converted into a cartel

- Marquis Cornwallis, brig, converted into a cartel

- Melpomene, brig, six guns, sent to Newport

- Miranda, schooner, divested and burned

- Prudence, brig, converted into a cartel

- HMS St. Lawrence, schooner, see above

Career after the War of 1812

On Chasseur's return to Baltimore on 15 April 1815, Niles' Register called the ship the "Pride of Baltimore".[9] She resumed her merchant career in the China trade. In 1816, she was sold to foreign investors and thereafter disappears from records.

"Pride of Baltimore"

Two replica ships were modeled after Chasseur and both were named Pride of Baltimore.

Paintings

Not many paintings of the Chasseur exist. One of them is "Chasseur capturing HMS St Lawrence" by Adam Weingartner of unknown date. The other is a painting of her by Danish-American artist Torsten Kruse that appeared in a book about Fell's Point.[10]

Citations

- Bourne, M. Florence (December 1954). "Thomas Kemp, Shipbuilder: and His Home, Wades Point". Maryland Historical Magazine. XLIX: 279.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton, 1863-1919 (1899). A history of American privateers. The Library of Congress: New York : D. Appleton and Co. p. 292.

- "Federal gazette & Baltimore daily advertiser". 17 December 1812.

- Dudley, William S. (2010). Maritime Maryland: A History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press in association with the Maryland Historical Society and the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8018-9475-6.

- Donnelly, Mark P. (2014). Pirates of Maryland : Plunder and High Adventure in the Chesapeake Bay. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811748865. OCLC 1022787251.

- Coggeshall, George (1861). History of the American privateers, and letters-of-marque during our war with England in the years 1812, '13 and '14 interspersed with several naval battles between American and British ships of war. G. Coggeshall. ISBN 0665443757. OCLC 1084236819.

- Lloyd's List 18 October 1814.

- Butler, James (1816). American bravery displayed, in the capture of fourteen hundred vessels of war and commerce, since the declaration of war by the president. Printed by George Phillips (for the author). ISBN 066547881X. OCLC 1083487993.

- Waldron, Tom (2004). Pride of the Sea: Courage, Disaster, and a Fight for Survival. New York: Citadel Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-8065-2492-8.

- Greff, Jacqueline, author. (2005). Fell's Point. p. 25. ISBN 9781467123983. OCLC 950745780.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- "Private Armed Vessels out of Baltimore and their prizes 1812 to 1815". War of 1812 Privateers.