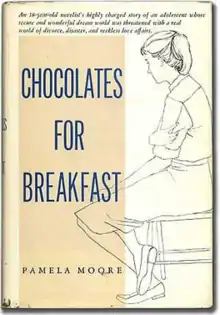

Chocolates for Breakfast

Chocolates for Breakfast is a 1956 American novel written by Pamela Moore. Originally published in 1956 when Moore was eighteen years old, the novel gained notoriety from readers and critics for its frank depiction of teenage sexuality, and its discussion of the taboo topics of homosexuality and gender roles.[1] The plot focuses on fifteen-year-old Courtney Farrell and her destructive upbringing between her father, a wealthy Manhattan publisher, and her mother, a faltering Hollywood actress.

First edition | |

| Author | Pamela Moore |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Rinehart & Company |

Publication date | January 1, 1956 |

Upon its release in 1956, the novel became an international sensation and was published in multiple languages,[2] with many critics drawing comparisons to the 1954 French novel Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan.[3] Chocolates for Breakfast went out of print in 1967, and was not reprinted in the United States until Harper Perennial re-released the novel in June 2013.[4] This marks its first re-printing in North America in over forty-five years.

Plot

The book opens with Courtney Farrell and her best friend Janet Parker at a New England boarding school, arguing over Courtney's attachment to her English teacher, Miss Rosen, whom Janet derides as "queer." Later the school pressures Miss Rosen to not talk to Courtney outside of class, and Courtney falls into a depression. She leaves school and joins her single mother, Sondra, in Hollywood. As Sondra struggles to find work as an actress, Courtney often has to take care of her and manage their situation. She also takes up with Sondra's friends, including Barry Cabot, a bisexual actor with whom she has an affair, though he breaks it off to return to his male lover.

Courtney often expresses a wish that she were born a man, as in this conversation with her teacher Miss Rosen:

"Don’t you think of yourself as a woman?” Miss Rosen said, amused.

"No, not really," Courtney said thoughtfully. "I don’t think the way they do. Men always tell me that I think like a man. It would be a lot simpler if I were a man. I guess. But maybe it wouldn’t be. .../... Since I can remember I’ve dreamt that I am a man. I hardly even notice now that in all my dreams I’m myself, but a man. I wonder why that is," she mused.

Courtney and Sondra move to New York, where Sondra hopes to work in television and where Courtney's father Robbie might be able to give them more support. There she reunites with her friend Janet and they go from cocktail parties at the Stork to all-night debutante balls on Long Island. Courtney becomes fascinated by Janet's friend Anthony Neville, an aristocratic esthete who lives out of the Pierre hotel and has homes in the Riviera and the Caribbean. She and Anthony become lovers but hide it from Janet, who was involved with him in the past.

Most of the characters in the book are heavy drinkers,[5] with the exception of Courtney and a young man named Charles Cunningham who gradually emerges as a love interest, although Courtney initially finds him too "straight arrow." Janet's father stands out as an alcoholic who "no longer cared for the niceties of companionship or ice in his bourbon." He often beats down the door behind which his wife and daughter hide from his rages. Janet leaves home to live first with Courtney and then with a lover. When she returns, her mother has fled to a sanitarium and her father is alone and drunk, and blames his daughter for ruining their lives.

Coldly, with the full force of his body, he slapped her...He fell upon her and forced her onto the couch and lay above her as a lover might, and she was terrified . . . As her body went limp in his arms he rose and walked over to the window. Thank God, she thought. Thank God he got up."

Soon after, Janet jumps from the window to her death. In the aftermath, Courtney ends her affair with Anthony. The novel ends with Courtney on her way to see Charles Cunningham and her parents for dinner, while Anthony contemplates returning to his island in the fall. The last line notes "how quickly the summer had gone."

Critical and scholarly response

Chocolates for Breakfast is sometimes included in lists[6][7] of early lesbian fiction, for the depiction of the relationship of two schoolgirls at an East Coast boarding school, Courtney's attachment to her teacher Miss Rosen, and the backlash against them from the other teachers and students. A detailed exploration of this genre, with a footnote linking Moore to the French tradition, appears in Contingent loves: Simone de Beauvoir and Sexuality by Melanie Hawthorne.[8]

Marion Zimmer Bradley, author of The Mists of Avalon, examined Chocolates for Breakfast in a 1965 article, "Feminine Equivalents of Greek Love in Modern Fiction," where she pronounced it "less melodramatic [than Faviell's Thalia] but perhaps more realistic and telling," and advanced the hypothesis that Courtney's 'sexual promiscuity and dissipation' could be traced to her rejection by Miss Rosen at the beginning of the book.[9]

In The Catalog Of Cool, filmmaker Richard Blackburn includes Chocolates for Breakfast which he describes as "the ultimate teen sophisticate fantasy."[5][10] Writer Rachel Shukert selected a passage from Chocolates for Breakfast as her inclusion in an anthology of erotic writing, calling it "a product of an all-too-brief vogue for novels about sexually precocious poor little rich girls."[11]

In popular culture

Alternative rock musician Courtney Love has stated that her mother, Linda Carroll, named her after the protagonist of the novel.[4][12]

As Robert Nedelkoff points out in his retrospective on the literary and social significance of Moore's work, the name Courtney became common as a girl's name only in the years after the novel's publication.[5]

In the series Feud, Joan Crawford is portrayed rejecting the book as a possible movie source.

References

- "Home". Chocolatesforbreakfast.info. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

- Moore, Pamela (June 2013). Chocolates for Breakfast. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780062246912.

- "Chocolates for Breakfast". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

- Matheson, Whitney (June 26, 2013). "I love this book: Chocolates for Breakfast". USA Today. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- Nedelkoff, Robert (1997). "Pamela Moore Plus Forty". The Baffler (10): 104–117. Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- "Chocolates for Breakfast", Lesbian Fun World, archived from the original on 2013-10-01, retrieved 2012-10-03

- "Goodreads:feminist--queer-and-sexxeee". Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- Hawthorne, Melanie (2000). Contingent loves: Simone de Beauvoir and sexuality. University of Virginia Press. pp. 82 n. 61.

- Marion Zimmer Bradley (1965). "Feminine Equivalents of Greek Love in Modern Fiction" (PDF). International Journal of Greek Love (1): 48–58. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- Gene Sculatti (October 1982). The Catalog of Cool. Warner Books. ISBN 978-0-446-37515-3. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- David Lehman (5 February 2008). The best American erotic poems: from 1800 to the present. Simon and Schuster. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4165-3745-8. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- "Courtney Love Discusses the Origin of Her Name". VH1.com. 2010-06-21. Retrieved 2013-06-26.

My mother named me after a book called Chocolates for Breakfast. That book's crazy, I didn't believe it was real. I find it on eBay, you know what it's about? It's about a fading has-been alcoholic actress who lives in the Chateau Marmont and the Garden of Allah [...] and her gay friend, in the Chateau [...] She and her mother both have sex by meeting at Schwab's, which is, by the way, my local drug store [...] This thinly-veiled bad boy method actor from New York, Brando-esque— not a James Dean type, because Frances read it and said "definitively Brando"— [anyway], they both have sex with him, and she eats chocolate for breakfast, and you know, has gin for dinner. It's, like, this fuckin' crazy book. Me and Frances were reading it, and I was like "Who's who? What's what?" It's obviously about a malignant narcissistic mother... why my mother named me [after it], I don't know.