Chott el Fejej

Chott el Fejej, also known as Chott el Fedjedj and Chott el Fejaj, is a long, narrow inlet of the endorheic salt lake Chott el Djerid in southern Tunisia.[1]

| Chott el Fejej | |

|---|---|

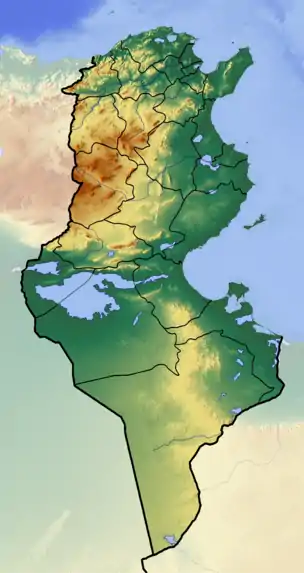

Chott el Fejej Chott el Fejej in Tunisia | |

| Coordinates | 33°52′N 9°13′E |

| Type | salt lake |

| Primary inflows | groundwater |

| Primary outflows | Terminal Evaporation |

| Basin countries | Tunisia |

| Max. length | 110 km (68 mi) |

| Max. width | 32 km (20 mi) |

History and geography

The bottom of Chott el Fejej lies below sea level and runs in a narrow path from the main body of Chott el Djerid to the Tunisian desert oasis of El Hamma, near the Gulf of Gabès on the Mediterranean Sea. The distance from the point where the Chott el Fejej joins the Chott el Djerid to its end near El Hamma is approximately 70 miles (110 km). Along its length, Chott el Fejej never widens beyond 20 miles (32 km) and in many places is considerably more narrow.[2] The easterly end of the Chott el Fejej is separated from Mediterranean by an approximately 13 miles (21 km) wide ridge of sand near El Hamma.[3]

It was this narrow sandy ridge, separating the Chott el Fejej from the Mediterranean Sea, which brought it to the attention of various geographers, engineers and diplomats. These figures looked to create an inland "Sahara Sea" by channelling the waters of the Mediterranean into Sahara Desert basins which lay below sea level. A noted proposal to this effect was put forward in the late 1800s by French geographer François Élie Roudaire and the creator of the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps, but stalled after the French government withdrew funding.[3][4][5] Later proposals, made as part of Operation Plowshare, posited that nuclear explosives could be used to dig the proposed canal from the Mediterranean to the Chott el Fejej and other below-sea-level basins of the Sahara; these proposals were also fruitless.[7]

Geology

The Chott el Fejej is a typical chott, or dry lake, of the Sahara. It is underlain, however, by a major anticline known as the Fejej Dome. This anticline and other surrounding structures are argued to be the result of rifting in the Cretaceous period.[8]

References

- Lisowscy, Andrzej; Lisowscy, Elżbieta (2011). DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Tunisia. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-0756684792. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Wheeler, Donna; Clammer, Paul; Filou, Emilie (2010). Tunisia (5th ed.). Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1741790016. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Plummer, Harry Chapin (1913). "A Sea in the Sahara". National Waterways: A Magazine of Transportation. National Rivers and Harbors Congress. 1 (2): 131–138. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Spinage, Clive Alfred (2012). African Ecology: Benchmarks and Historical Perspectives. Springer Geography (Illustrated ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3642228711. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- McKay, Donald Vernon (1943). "Colonialism in the French geographical movement 1871-1881". Geographical Review. American Geographical Society. 33 (2): 214–232. doi:10.2307/209775. JSTOR 209775.

- Jousiffe, Ann (2010). Tunisia. Globetrotter: Guide and Map Series (4th ed.). London: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 978-1845378646. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Gharbi, Mohamed; Masrouhi, Amara; Espurt, Nicolas; Bellier, Olivier; Amari, El Amjed; Ben Youssef, Mohamed; Ghanmi, Mohamed (March 2013). "New tectono-sedimentary evidences for Aptian to Santonian extension of the Cretaceous rifting in the Northern Chotts range (Southern Tunisia)" (PDF). Journal of African Earth Sciences. Elsevier Ltd. 79: 58–73. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2012.09.017.