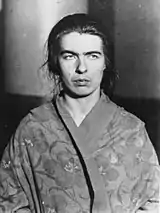

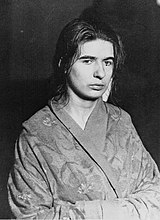

Christine and Léa Papin

Christine Papin (8 March 1905 – 18 May 1937) and Léa Papin (15 September 1911 – 24 July 2001, or 1982, see Death) were two French sisters. As live-in maids, they were convicted of murdering their employer's wife and daughter in Le Mans, France on February 2, 1933.

The murder had a significant influence on French intellectuals Jean Genet, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Jacques Lacan, who sought to analyze it, and some considered it symbolic of class struggle. The case formed the basis of a number of publications, plays, and films, as well as essays, spoken word, songs, and artwork.

Life

Born in Le Mans, France to Clémence Derré and Gustave Papin, the Papin sisters came from a troubled family. While Clémence was dating Gustave, it was rumored that she was having an affair with her employer. However, after she became pregnant, Gustave married her in October 1901. Five months later, daughter Emilia was born.

Suspecting that Clémence was still having an affair with her employer, Gustave found a new job in another city and announced the family would move. Clémence declared she would rather commit suicide than leave Le Mans. The marriage deteriorated. Gustave began to drink heavily.

Early life

Christine was born on March 8, 1905 and given to her paternal aunt and uncle soon after birth. She lived happily with them for seven years. Léa was born on September 15, 1911 and given to her maternal uncle, with whom she remained until he died.

In 1912, when Emilia was 9 or 10 years old, it was alleged that Gustave had raped her, and Clémence sent her to the Bon Pasteur Catholic Orphanage. Soon afterward, Emilia was joined by her sisters Christine and Léa, whom Clémence intended would remain at the orphanage until age 15, when they could be employed.

Clémence and Gustave divorced in 1903[1913?]..

In 1918, Emilia decided to enter a convent, effectively ending her relations with her family. As far as can be ascertained, she lived out the remainder of her life there.

During Christine's time at the orphanage, she also received the calling to become a nun. Clémence forbade this, instead placing her in employment. Christine was described as a hard worker and a good cook who could be insubordinate at times. Léa was described as quiet and introverted but obedient, and was considered less intelligent than Christine.

The sisters worked as maids in various Le Mans homes. They preferred to work together whenever possible.

Crime

In 1926 Christine and Léa found live-in positions as maids at 6 rue Bruyère for the Lancelin family; M. René Lancelin, a retired solicitor, his wife Léonie, and their younger daughter Genevieve lived in the house (an elder daughter was married). Some years after Christine and Léa started working for the family, Madame Léonie developed depression and the girls became the target of her mental illness. The abuse worsened to the point that she would slam the girls' heads against the wall.

On the evening of Thursday, February 2, 1933, Monsieur Lancelin was supposed to meet Madame Léonie and Genevieve for dinner at the home of a family friend. Madame Léonie and Genevieve had been out shopping that day. When they returned home that afternoon, no lights were on in the house. The Papin sisters explained to Madame Lancelin that the power outage had been caused by Christine urinating into an electrical socket. Madame Lancelin became irate and attacked the sisters on the first-floor landing. Christine lunged at Genevieve and gouged her eyes out. Léa joined in the struggle and attacked Madame Lancelin, gouging her eyes out as ordered by Christine. Christine ran downstairs to the kitchen where she retrieved a knife and a hammer. She brought both weapons upstairs, where the sisters continued their attack. At some point one of the sisters grabbed a heavy pewter pitcher and used it to strike both Lancelin women on the head. Experts who later responded to the scene estimated that the attack lasted about 2 hours.

Some time later, Monsieur Lancelin returned home to find the house dark. He assumed that his wife and daughter had left for the dinner party and proceeded to the party himself. When he arrived at his friend's home, he found that his family was not there, either. He returned to his residence with his son-in-law at approximately 18:30 - 19:00, where they discovered the entire house still dark except for a light in the Papin sisters' room. The front door was bolted shut from the inside, so they were unable to enter the house. The two men found this suspicious and went to a local police station to summon help from an officer. Together with the policeman they responded to the Lancelin home where the policeman made entry into the home by climbing over the garden wall. Once inside, he found the bodies of Madame Lancelin and her daughter Genevieve. They had both been bludgeoned and stabbed to the point of being unrecognizable. Madame Lancelin's eyes had been gouged out and were found in the folds of the scarf around her neck, and one of Genevieve's eyes was found under her body and another on the stairs nearby. Thinking that the Papin sisters had met the same fate, the policeman continued upstairs only to find the door to the Papin sisters' room locked. After the officer knocked but received no response, he summoned a locksmith to open the door. Inside the room he found the Papin sisters naked in bed together, and a bloody hammer, with hair still clinging to it, was on a chair nearby.[1] Upon questioning, the sisters immediately confessed to the killing.

Trial and imprisonment

The sisters were placed in prison and separated from each other. Christine became extremely distressed because she could not see Léa. At one point prison officials relented and allowed the two sisters to meet. Christine reportedly threw herself at Léa, unbuttoning her blouse, begging her "Please, say yes!" suggesting an incestuous sexual relationship.[1]

In July 1933, Christine experienced a "fit", or episode, in which she tried to gouge her own eyes out and had to be put in a straitjacket. She then made a statement to the investigating magistrate, in which she said that on the day of the murders she had experienced an episode like the one she just had in prison, and that this was what precipitated the murders.[1]

The court appointed three doctors to administer psychological evaluations of the sisters to determine their mental state. They concluded that the two had no pathological mental disorders and deemed them sane and fit to stand trial. They also believed that Christine's affection for her sister was based on family ties, not an incestuous relationship as others had suggested.

However, during the September 1933 trial, medical testimony noted a history of mental illness in the family. Their uncle had committed suicide, while their cousin was living in an asylum. The psychological community struggled and debated over a diagnosis for the sisters. After much consideration it was concluded that Christine and Léa suffered from "Shared Paranoid Disorder", which is believed to occur when groups or pairs of people are isolated from the world, developing paranoia, and in which one partner dominates the other. This was especially true of Léa, whose meek personality was overshadowed by obstinate and dominant Christine.

After the trial, jurors took 40 minutes to determine that the Papin sisters were indeed guilty of the heinous crime of which they had been accused. Léa, thought to be under the influence of her older sister, was given a 10-year sentence. Christine was initially sentenced to death at the guillotine, although that sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

Death

The separation from Léa proved to be too much for Christine. Her condition deteriorated rapidly once they were apart. She experienced bouts of depression and "madness", eventually refusing to eat. Prison officials transferred her to a mental institution in Rennes, hoping that she would benefit from professional help. Still separated from Léa, she continued to starve herself until she died of cachexia ("wasting away") on May 18, 1937.[2]

Léa fared better than Christine, serving only eight years of her 10-year sentence. After her release in 1941, she lived in the town of Nantes, where she was joined by her mother. She assumed a false identity and earned a living as a hotel maid.[3]

Some accounts state that Léa died in 1982, but French film producer Claude Ventura claims to have discovered Léa living in a hospice center in France in 2000 while creating the film En Quête des Soeurs Papin (in English In Search of the Papin Sisters). The woman he claimed to be Léa had suffered a stroke which had rendered her partially paralyzed and unable to speak. This woman died in 2001.[4]

Aftermath

The case had a huge impact on the community and was debated intensely by the intelligentsia. Some people considered that the murders had been the result of "exploitation of the workers", considering that the maids worked fourteen-hour days, with only a half-day off each week. Intellectuals empathized with the sisters' oppressive struggle of the social classes.

Works inspired by the case

- The Maids (Les Bonnes), a play by Jean Genet

- The Maids, a film based on the play, directed by Christopher Miles

- My Sister in This House, a play by Wendy Kesselman

- Sister My Sister, a 1994 film by Nancy Meckler, adapted from her play

- Les Abysses, a film directed by Nikos Papatakis

- La Cérémonie, a film directed by Claude Chabrol

- Violets, a 2015 short film directed by Jim Vendiola[5][6][7]

- Les Soeurs Papin, a book by R. le Texier

- Blood Sisters, a stage play and screenplay by Neil Paton

- L'Affaire Papin, a book by Paulette Houdyer

- La Solution du passage à l'acte, a book by Francis Dupré

- "The Murder in Le Mans," an essay in Paris Was Yesterday, a book by Janet Flanner

- La Ligature, a short film by Gilles Cousin

- Les Meurtres par Procuration, a book by Jean-Claude Asfour

- Lady Killers, a book by Joyce Robins

- Minotaure #3, 1933, a magazine

- The Maids, an opera by Peter Bengtson

- Les Blessures assassines (English : Murderous Maids), a film by Jean-Pierre Denis

- En Quete des Soeurs Papin (In Search of the Papin Sisters), a documentary film by Claude Ventura

- Gros Proces des l'Histoire, a book by M. Mamouni

- L'Affaire Papin, a book by Genevieve Fortin

- The Papin Sisters, a book by Rachel Edwards and Keith Reader

- The Maids, an artwork by Paula Rego

- Anna la bonne, a 1934 "spoken song" written by Jean Cocteau and performed by Marianne Oswald.[8] This was inspired by Poe's Annabel Lee rather than the Papin case, but it influences Genet's "Les Bonnes".[9]

- Possibly "Tomorrow," episode 2.7 of the television series Law & Order Criminal Intent

- Deadly Women (Double Trouble)

- Maids, a comic by Katie Skelly

- Parasite, a film by Bong Joon-ho[10]

Les Bonnes by Jean Genet

The play Les Bonnes by French writer Jean Genet often is thought to be based on the Papin sisters, although Genet said this was not the case. However, the play deals with the plight of two French maids who resemble the Papin sisters, and highlights the dissatisfaction of the maids with their lot in life, which manifests itself in a hatred for their mistress. Genet's interest in the crime of the Papin sisters stemmed at least partly from his contempt for the middle classes, along with his understanding of how a murderer could glory in the infamy that came from the crime.

See also

- Case of Aimée

- Popular Front (France), for more on the political climate of the times.

References

- Dupré 1984, pp. 17–265

- Hall 1976, p. 151.

- Edwards & Reader 1984, pp. 4–19.

- Paton, Neil. "New Pictures of the Papin Sisters". Christine and Lea Papin and Other Studies in Crime. Retrieved 2020-09-28.

- ""Violets" a film by Jim Vendiola". violetsfilm.com. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- "Perrier — Introducing the Winners of the 2015 Chicago..." Perrier. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Vendiola, Jim; Jones, Cassandra; Siffermann, Annie (24 April 2015), Violets, retrieved 20 December 2016

- La travail en chansons Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Anna la bonne (in French)

- "Cocteau".

- "Bong Joon Ho on Why He Wanted Parasite to End With a Surefire Kill".

Bibliography

- Dupré, Francis (1984). La solution du passage à l'acte [The Solution of Acting Out] (in French). Paris: Éditions Érès. ISBN 978-2-86586-024-1.

- Edwards, Rachel; Reader, Keith (1984). The Papin Sisters. Oxford Studies in Modern European Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816010-6.

- Hall, Angus, ed. (1976). "The Maids of Horror". Crimes of Horror (1st ed.). Great Britain: The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp. 148–155. ISBN 1-85051-170-5.

Further reading

- Houdyer, Paulette (1988). L'Affaire Papin [The Papin Case] (in French). Le Mans: Éditions Cénomane. ISBN 978-2-905596-33-8.

External links

![]() Media related to Christine and Lea Papin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christine and Lea Papin at Wikimedia Commons