Citizen media

Citizen media is content produced by private citizens who are not professional journalists. Citizen journalism, participatory media and democratic media are related principles.

Background

"Citizen media" was coined by Clemencia Rodriguez, who defined it as 'the transformative processes they bring about within participants and their communities.'[1] Citizen media characterizes the ways in which audiences can become participants in the media using various resources by new media technologies.

Citizen media has bloomed with the advent of technological tools and systems that facilitate production and distribution of media, notably the Internet. With the birth of the Internet and into the 1990s, citizen media has responded to traditional mass media's neglect of public interest and partisan portrayal of news and world events.

By 2007, the success of small, independent, private journalists began to rival corporate mass media in terms of audience and distribution. Citizen produced media has earned higher status and public credibility since the 2004 US Presidential elections and has since been widely replicated by corporate marketing and political campaigning. Citizen media usage and attention also increased in reaction to the 2016 US Presidential election. Traditional news outlets and commercial media giants have experienced declines in profit and revenue which can be directly attributed to the wider acceptance of citizen produced media as an official source of information.[2]

Definition

Many people prefer the term 'participatory media' to 'citizen media' as citizen has a necessary relation to a concept of the nation-state. The fact that many millions of people are considered stateless and often without citizenship limits the concept to those recognised only by governments. Additionally the very global nature of many participatory media initiatives, such as the Independent Media Center, makes talking of journalism in relation to a particular nation-state largely redundant as its production and dissemination do not recognise national boundaries.

A different way of understanding Citizen Media emerged from cultural studies and the observations made from within this theoretical frame work about how the circuit of mass communication was never complete and always contested, since the personal, political, and emotional meanings and investments that the audience made in the mass-distributed products of popular culture were frequently at odds with the intended meanings of their producers.[3]

Criticism

Media produced by private citizens may be as factual, satirical, neutral or biased as any other form of media but has no political, social or corporate affiliation. There is often no training or understanding of professional concepts - such as off-record, objectivity, and balance - amongst those who produce their own media. Some argue that ordinary citizens may do more harm than good if they are able to publish their personal thoughts and opinions and pass them off as legitimate journalism.[4]

The following are ways that citizen media negatively differentiates from traditional journalism, according to critics:

Bias can be a problem in citizen media because there are multiple steps traditional journalists must undergo before publishing, such as waiting for confirmation before reporting a story. These steps do not always carry over to citizen media publication because they are not affiliated with any entity that would have additional editors. This can result in a lack of accountability and a strong presence of personal bias.

Transparency is another point of criticism. In citizen media, the user generating the content is often anonymous, hidden by a username. In traditional media, however, the reporter or editor's identity is known and can be identified by their byline. Conversely, there are some forms of citizen media, in which the author is known; this is most often in blogs.

Modes

There are many forms of citizen-produced media including blogs, vlogs, podcasts, digital storytelling, community radio, participatory video and more, and may be distributed via television, radio, internet, email, movie theatre, DVD and many other forms. Many organizations and institutions exist to facilitate the production of media by private citizens including, but not limited to, Public, educational, and government access (PEG) cable tv channels, Independent Media Centers and community technology centers.

Print

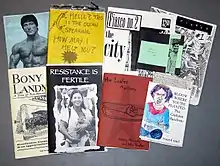

Zines are an example of citizen media. According to Barnard College, there are various definitions for zines, but they share the following features: "self-published and the publisher does not answer to anyone; small, self-distributed print run; motivated by the desire to express oneself rather than to make money; outside the mainstream; low budget." [5]

Zines are self-published and free of any responsibility to an internet service provider, as blogs are. As a result, creators are able to bypass traditional journalism guidelines, such as copyright and ethical considerations.

Radio

World Wide Community Radio has been driven by participatory methodologies with rich examples of community radio providing a non-profit community owned, operated and driven model of media.

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) in the United States initiated by the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967 sets aside some public broadcasting funding for producing electronic television programming. Traditionally, PBS radio affiliates have not made concessions for private citizen programming or production.

- Stations like WBAI, KPFA, KPFK, and Pacifica Radio Network have program models which allow citizen participation in aspects of the station, including production.

- Many low power Federal Communications Commission (FCC) non-commercial educational (NCE) license holders are considered community radio stations (including high school radio and college radio), with various levels of participation by the public.

Television

With the birth of cable television in the 1950s came public interest movements to democratize this new booming industry. Many countries around the world developed legislated means for private citizens to access and use the local cable systems for their own community-initiated purposes.

- Public Access Television (PEG) in the United States is a government mandated model that provides citizens within a cable franchised municipality to get access to the local Public-access television channels to produce and distribute their own programming. Public-access television programming is community initiated and serves as a platform to meet local needs.

- Community channels in Canada also provides access for citizens to distribute their own programming content, as well as community television in Australia.

- Community technology centers are private non-profit organizations found in the US that serve to increase access and training in technology for social applications.

Television is not as relevant or widely used in American culture as it was in the 1950s, or even in the past decades. A study in 1990 found that Americans spend an average of seven years watching television.[6] However, other forms of media, such as online streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime, have both supplemented and replaced television as a common form of visual media for entertainment and news.

Internet

Affordable consumer technology and broader access to the internet has created new electronic distribution methods. While the corporate media market enjoyed a long period of monopoly on media distribution, the internet gave birth to countless independent media producers and new avenues for delivering content to viewers.

- Citizen Journalism websites which encourage members of the public to publish news that is relevant to them.

- The social development of Independent Media Centers (IMCs) introduced collaborative Citizen media with concepts of consensus decision making, mandatory inclusion of women and minorities, non-corporate control, the anonymous accreditation. IMCs have been founded in over 200 cities all over the world.

- Commercial models that use these new methods are being born and acquired by media corporations on a daily basis.

- We can see some examples about citizen press like https://web.archive.org/web/20121211035127/http://mwatenpress.com/ CMS in Arabic language.

- The technological development of Content Management Systems (CMS) in the late 1990s, which allowed non-technical people to author and publish articles to the internet, spawned the birth of weblogs or blogs, Podcasting (audio blogs), Vlogs (video blogs), collaborative wikis, and web-based bulletin boards and "forums".[7]

Blogs

The Guardian named HuffPost (formerly known as The Huffington Post before their rebranding in 2017) the world's most powerful blog in 2008.[8] "The Huffington Post became one of the most influential and popular journals on the web. It recruited professional columnists and celebrity bloggers," reported The Guardian in their "The world's 50 most powerful blogs" article.[9] The HuffPost qualifies as citizen media as defined earlier in the article because audiences can also become participants in and interact with the media using the different resources offered; HuffPost writers are not always professional journalists.

Video

Participatory video is an approach to and medium of participatory or citizen media that has become increasingly popular with the falling cost of film/video production, availability of simple consumer video cameras and other equipment, and ease of distribution via the Internet.

Although videos/films can be produced by a single individual, production often requires a group of participants. And, so participatory filmmaking includes a set of techniques to involve communities/groups in conceptualizing and producing their own films. Chris Lunch, a preeminent contemporary author on participatory video and executive director of Insight, explains that “The idea behind this is that making a video is easy and accessible, and is a great way of bringing people together to explore issues, voice concerns, or simply to be creative and tell stories.”[10]

Participatory video was developed in opposition to more traditional documentary film approaches, in which indigenous knowledge and local initiatives are filmed and disseminated by outside professional filmmakers. These professionals, who are often from relatively privileged backgrounds use their artistic license to design narrative stories and interpret the meaning of the images/actions that they film. As such, the film is often created for the benefit of outsiders and those that are filmed rarely benefit from their participation. The objectives of participatory video are to facilitate empowerment, community self-sufficiency, and communication.[11]

Origins

The first experiments in PV were the work of Don Snowden, a Canadian who pioneered the idea of using media to enable a people-centered community development approach. Then Director of the Extension Department at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Snowden worked with filmmaker Colin Low and the National Film Board of Canada's Challenge for Change program to apply his ideas in Fogo Island, Newfoundland, a small fishing community.[12][13]

By watching each other's films, the villagers realized that they shared many of the same concerns and they joined together to create solutions. The villager's films were shared with policy-makers, many of whom had no real conception of the conditions in which Fogo Islanders lived. As a result of this dialogue, policy-makers introduced regulation changes. Snowden went on to apply the Fogo process all over the world until his death in India in 1984.[14] Since then, most of the development of the participatory video technique has been led by non-academic practitioners in the United Kingdom, France, Australia, and Canada.

YouTube

Created in 2005, YouTube has become one of the largest original video publishing sites over the past decade. It was initially thought of as a vast space for random content. A year after its creation, YouTube was suddenly being referred to as "the first signs of a post-television age, a focus of serious media industry interest, the site of new and difficult legal issues and moral and ethical concerns."[15] YouTube has quickly become an outlet for both news channels and individual users to post news and other media content. Major news networks such as CNN, NBC, BBC, and Fox News, have their own channels where they post clips of broadcasts and interviews.

Participatory videos are distributed online and offline. Online, they are uploaded and shared through vlogs, social software, and video publishing sites. Aligning with the objective of participatory video to create community and communication, YouTube currently has a strong community of over one billion users who watch a billion hours of video daily.[16] The ability of users to choose media sources and which content they want to view adds to the concept of personalized media, a major component of citizen media.

See also

References

- Meikle Graham, Networks of Influence: Internet Activisim in Australia and Beyond" in Gerard Goggin (ed.)Virtual Nation: the Internet in Australia University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, pp 73-87.

- Peter Leyden, New Politic Institute Archived 2007-04-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Flew, Terry "New Media: An Introduction". Oxford University Press, Melbourne.

- BARNES, CORINNE (2012). "Citizen Journalism vs. Traditional Journalism: A Case for Collaboration". Caribbean Quarterly. 58 (2/3): 16–27. JSTOR 41708775.

- "Definition | Barnard Zine Library". zines.barnard.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Storey, John (2010). Cultural Studies and the Study of Popular Culture (NED - New edition, 3 ed.). Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/j.ctt1g0b5qb.5.pdf. ISBN 9780748640386. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g0b5qb.

- The more proper "fora" is rarely used in this context.

- Aldred, Jessica; Behr, Rafael; Pickard, Anna; Wignall, Alice; Hind, John; Cochrane, Lauren; Wiseman, Eva; Potter, Laura (2008-03-09). "The world's 50 most powerful blogs". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- Aldred, Jessica; Behr, Rafael; Pickard, Anna; Wignall, Alice; Hind, John; Cochrane, Lauren; Wiseman, Eva; Potter, Laura (2008-03-09). "The world's 50 most powerful blogs". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

- Lunch, N., & Lunch, C. (2006). Insights Into Participatory Video: A Handbook for the Field (1st ed.). Oxford: Insight.

- Lunch, C. (2004). Participatory Video: Rural People Document their Knowledge and Innovations. Indigenous Knowledge Notes; 71.

- Quarry, Wendy. The Fogo Process: An Experiment in Participatory Communication. 1994: Thesis, University of Guelph. Archived from the original on 2001-11-04. Retrieved 2009-10-16.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Schugurensky, Daniel (2005). "Challenge for Change launched, a participatory media approach to citizenship education". History of Education. The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto (OISE/UT). Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- Lunch, C. (2006, March). Participatory Video as a Documentation Tool. Leisa Magazine, 22, 31-33.

- Storey, John (2010). Cultural Studies and the Study of Popular Culture (NED - New edition, 3 ed.). Edinburgh University Press. doi:10.3366/j.ctt1g0b5qb.5.pdf. ISBN 9780748640386. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1g0b5qb.

- "Press - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2018-03-02.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Citizen media. |

- Bulletin by Openreporter- An app to share your story directly with journalists.

- The VideoVoice Collective does research and evaluation on participatory video.

- Center for Citizen Media

- Media Democracy Day

- Media Democracy Project

- Center for Media and Democracy

- Demosphere Project — The wiki & global project to develop a community based media framework using open source and interactive software. (Wikinews article)

- McChesney, Robert, Making Media Democratic, Boston Review, Summer 1998

- Inclusion Through Media: First hand accounts and critical analysis of work across the Inclusion Through Media programme edited by Tony Dowmunt, Mark Dunford and Nicole van Hemert.