Classical planet

In classical antiquity, the seven classical planets or seven sacred luminaries are the seven moving astronomical objects in the sky visible to the naked eye: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. The word planet comes from two related Greek words, πλάνης planēs (whence πλάνητες ἀστέρες planētes asteres "wandering stars, planets") and πλανήτης planētēs, both with the original meaning of "wanderer", expressing the fact that these objects move across the celestial sphere relative to the fixed stars.[1][2] Greek astronomers such as Geminus[3] and Ptolemy[4] often divided the seven planets into the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets.

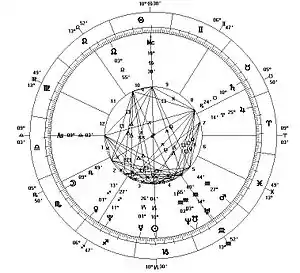

| Astrology |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

The term planet in modern terminology is only applied to natural satellites directly orbiting the Sun, so that of the seven classical planets, five are planets in the modern sense. The same 7 planets, along with the ascending and descending lunar node, are mentioned in Vedic astrology as the nine Navaratna.

Babylonian astronomy

The Babylonians recognized seven planets. A bilingual list in the British Museum records the seven Babylonian planets in this order: [5]

| Sumerian language | Akkadian language | Celestial object | Presiding deity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aku | Sin | Moon | Sin/Suen |

| Bišebi | Šamaš | Sun | Šamaš |

| Dapinu | Umun-sig-êa | Jupiter | Marduk/Amarutu |

| Zib/Zig | Dele-bat | Venus | Ištar |

| Lu-lim | Lu-bat-sag-uš | Saturn | Ninib/Nirig/Ninip,[lower-alpha 1][6] possibly Anu[7] |

| Bibbu | Lubat-gud | Mercury | Nabu/Nebo |

| Simutu | Muštabarru | Mars | Nergal |

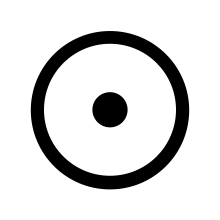

Symbols

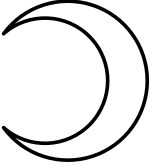

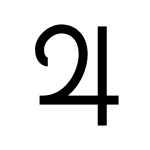

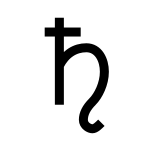

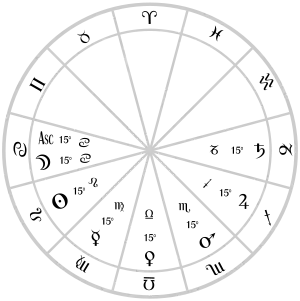

The astrological symbols for the classical planets appear in the medieval Byzantine codices in which many ancient horoscopes were preserved.[8] In the original papyri of these Greek horoscopes, there are found a circle with one ray (![]() ) for the Sun and a crescent for the Moon.[9]

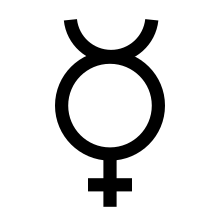

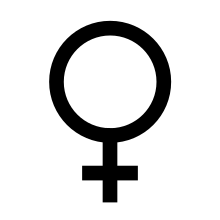

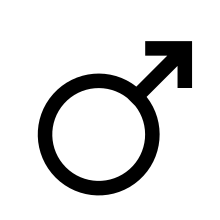

The written symbols for Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn have been traced to forms found in late Greek papyri.[10] The symbols for Jupiter and Saturn are identified as monograms of the initial letters of the corresponding Greek names, and the symbol for Mercury is a stylized caduceus.[10]

) for the Sun and a crescent for the Moon.[9]

The written symbols for Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn have been traced to forms found in late Greek papyri.[10] The symbols for Jupiter and Saturn are identified as monograms of the initial letters of the corresponding Greek names, and the symbol for Mercury is a stylized caduceus.[10]

A. S. D. Maunder finds antecedents of the planetary symbols in earlier sources, used to represent the gods associated with the classical planets. Bianchini's planisphere, produced in the 2nd century,[11] shows Greek personifications of planetary gods charged with early versions of the planetary symbols: Mercury has a caduceus; Venus has, attached to her necklace, a cord connected to another necklace; Mars, a spear; Jupiter, a staff; Saturn, a scythe; the Sun, a circlet with rays radiating from it; and the Moon, a headdress with a crescent attached.[12] A diagram in Johannes Kamateros' 12th century Compendium of Astrology shows the Sun represented by the circle with a ray, Jupiter by the letter zeta (the initial of Zeus, Jupiter's counterpart in Greek mythology), Mars by a shield crossed by a spear, and the remaining classical planets by symbols resembling the modern ones, without the cross-mark seen in modern versions of the symbols.[12] The modern Sun symbol, pictured as a circle with a dot (☉), first appeared in the Renaissance.[9]

Planetary hours

The Ptolemaic system used in Greek astronomy placed the planets in order, closest to Earth to furthest, as the Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. In addition the day was divided into 7 hour intervals, each ruled by one of the planets, although the order was staggered (see below).

The first hour of each day was named after the ruling planet, giving rise to the names and order of the Roman seven-day week. Modern Latin-based cultures, in general, directly inherited the days of the week from the Romans and they were named after the classical planets; for example, in Spanish Miércoles is Mercury, and in French Mardi is Mars-day.

The modern English days of the week were inherited from gods of the old Germanic Norse culture — Wednesday is Wōden’s-day (Wōden or Wettin eqv. Mercury), Thursday is Thor’s-day (Thor eqv. Jupiter), Friday is Frige-day (Frig eqv. Venus). It can be correlated that the Norse gods were attributed to each Roman planet and its god, probably due to Roman influence rather than coincidentally by the naming of the planets.

| Weekday | Planet | Greek god | Germanic god | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English name | Roman god | Greek name | Norse name | Saxon name |

| Sunday | Sol | Helios | Sól | Sunne |

| Monday | Luna | Selene | Máni | Mōnda |

| Tuesday | Mars | Ares | Týr | Tīw |

| Wednesday | Mercury | Hermes | Óðinn | Wōden / Wettin |

| Thursday | Jupiter | Zeus | Thórr | Thunor |

| Friday | Venus | Aphrodite | Frigg | Frige |

| Saturday | Saturn | Cronus | Njörðr[13] | Njord[13] |

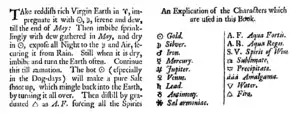

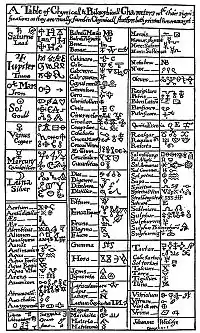

Alchemy

In alchemy, each classical planet (Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) was associated with one of the seven metals known to the classical world (silver, mercury/quicksilver, copper, gold, iron, tin and lead respectively). As a result, the alchemical glyphs for the metal and associated planet coincide. Alchemists believed the other elemental metals were variants of these seven (e.g. zinc was known as "Indian tin" or "mock silver"[14]).

Alchemy in the Western World and other locations where it was widely practiced was (and in many cases still is) allied and intertwined with traditional Babylonian-Greek style astrology; in numerous ways they were built to complement each other in the search for hidden knowledge (knowledge that is not common i.e. the occult). Astrology has used the concept of classical elements from antiquity up until the present day today. Most modern astrologers use the four classical elements extensively, and indeed they are still viewed as a critical part of interpreting the astrological chart.

Traditionally, each of the seven "planets" in the solar system as known to the ancients was associated with, held dominion over, and "ruled" a certain metal (see also astrology and the classical elements).

The list of rulership is as follows:

- The Sun rules Gold (

)

) - The Moon, Silver (

)

) - Mercury, Quicksilver/Mercury (

)

) - Venus, Copper (

)

) - Mars, Iron (

)

) - Jupiter, Tin (

)

) - Saturn, Lead (

)

)

Some alchemists (e.g. Paracelsus) adopted the Hermetic Qabalah assignment between the vital organs and the planets as follows:[14]

| Planet | Organ |

| Sun | Heart |

| Moon | Brain |

| Mercury | Lungs |

| Venus | Kidneys |

| Mars | Gall bladder |

| Jupiter | Liver |

| Saturn | Spleen |

Contemporary astrology

Western astrology

| Planet | Domicile sign(s) | Detriment sign(s) | Exaltation sign | Fall sign | Joy sign(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Leo | Aquarius | Aries | Libra | Sagittarius |

| Moon | Cancer | Capricorn | Taurus | Scorpio | Pisces, Libra |

| Mercury | Gemini (diurnal) and Virgo (nocturnal) | Sagittarius (diurnal) and Pisces (nocturnal) | Virgo | Pisces | Aries, Scorpio, Capricorn and Aquarius |

| Venus | Libra (diurnal) and Taurus (nocturnal) | Aries (diurnal) and Scorpio (nocturnal) | Pisces | Virgo | Gemini, Cancer and Aquarius |

| Mars | Aries (diurnal) and Scorpio (nocturnal) | Libra (diurnal) and Taurus (nocturnal) | Capricorn | Cancer | Gemini, Leo, Virgo and Sagittarius |

| Jupiter | Sagittarius (diurnal) and Pisces (nocturnal) | Gemini (diurnal) and Virgo (nocturnal) | Cancer | Capricorn | Taurus, Leo and Libra |

| Saturn | Aquarius (diurnal) and Capricorn (nocturnal) | Leo (diurnal) and Cancer (nocturnal) | Libra | Aries | Gemini, Virgo and Scorpio |

Indian astrology

Indian astronomy and astrology (Jyotiṣa) recognises seven visible planets (including the sun and moon) and two additional invisible planets.

| Sanskrit Name | Tamil name | English Name | Guna | Represents | Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surya (सूर्य) | ஞாயிறு (ñāyiṟu) | Sun | Sattva | Soul, king, highly placed persons, father, ego | Sunday |

| Chandra (चंद्र) | திங்கள் (tiṅkaḷ), மதி (mathi), நிலவு (nilavu) | Moon | Sattva | Emotional Mind, queen, mother. | Monday |

| Mangala (मंगल) | செவ்வாய் (cevvāy), செம்மீன் (cem'mīṉ) | Mars | Tamas | energy, action, confidence | Tuesday |

| Budha (बुध) | புதன் (putaṉ), அறிவன் (aṟivaṉ) | Mercury | Rajas | Communication and analysis, mind | Wednesday |

| Brihaspati (बृहस्पति) | வியாழன் (viyāḻaṉ), பொன்மீன் (poṉmīṉ) | Jupiter | Sattva | the great teacher, wealth, Expansion, progeny | Thursday |

| Shukra (शुक्र) | வெள்ளி (veḷḷi), வெண்மீன் (veṇmīṉ) | Venus | Rajas | Feminine, pleasure and reproduction, Luxury, Love, Spouse | Friday |

| Shani (शनि) | சனி (saṉi), காரி (kāri), மைம்மீன் (maim'mīṉ) | Saturn | Tamas | learning the hard way. Career and Longevity, Contraction | Saturday |

| Rahu (राहु) | கரும்பாம்பு (karumpāmpu) | Ascending/North Lunar Node | Tamas | an Asura who does his best to plunge any area of one's life he controls into chaos, works on the subconscious level | none |

| Ketu (केतु) | செம்பாம்பு (cempāmpu) | Descending/South Lunar Node | Tamas | supernatural influences, works on the subconscious level | none |

Chinese astronomy

The cycles of the Chinese calendar are linked to the orbit of Jupiter, there being 12 sacred beasts in the Chinese dodecannualar geomantic and astrological cycle, and 12 years in the orbit of Jupiter.

| English Name | Associated element | Chinese/Japanese/Korean Hanja Characters | Chinese pinyin | Japanese hiragana/romaji | Korean Hangul (romaja) | Vietnamese | Old astronomical names[15] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | water | 水星 | Shuǐxīng | すいせい/Suisei | 수성 (Suseong) | Sao Thủy | Chénxīng (辰星) |

| Venus | metal/gold | 金星 | Jīnxīng | きんせい/Kinsei | 금성 (Geumseong) | Sao Kim, also "Sao Mai" as "morning star" and "Sao Hôm" as "evening star" | Tàibái (太白) |

| Mars | fire | 火星 | Huǒxīng | かせい/Kasei | 화성 (Hwaseong) | Sao Hỏa | Yínghuò (熒惑) |

| Jupiter | wood | 木星 | Mùxīng | もくせい/Mokusei | 목성 (Mokseong) | Sao Mộc | Suì (歲) |

| Saturn | earth | 土星 | Tǔxīng | どせい/Dosei | 토성 (Toseong) | Sao Thổ | Zhènxīng (鎮星) |

Naked-eye planets

Mercury and Venus are visible only in twilight hours because their orbits are interior to that of Earth. Venus is the third-brightest object in the sky and the most prominent planet. Mercury is more difficult to see due to its proximity to the Sun. Lengthy twilight and an extremely low angle at maximum elongations make optical filters necessary to see Mercury from extreme polar locations.[16] Mars is at its brightest when it is in opposition, which occurs approximately every twenty-five months. Jupiter and Saturn are the largest of the five planets, but are farther from the Sun, and therefore receive less sunlight. Nonetheless, Jupiter is often the next brightest object in the sky after Venus. Saturn's luminosity is often enhanced by its rings, which reflect light to varying degrees, depending on their inclination to the ecliptic; however, the rings themselves are not visible to the naked eye from the Earth. Uranus and sometimes the asteroid Vesta are in principle visible to the naked eye on very clear nights, but, unlike the true naked-eye planets, are always less luminous than several thousands of stars, and as such, do not stand out enough for their existence to be noticed without the aid of a telescope.

Notes

- Sumerian names for the planet Saturn are Kâawanu and (Akkadian) Sag-uš "firm, steadfast, phlegmatic".

See also

References

- Classification of the Planets

- πλάνης, πλανήτης. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Goldstein, Bernard R. (2007), "What's New in Ptolemy's Almagest", Nuncius, 22 (2): 271, doi:10.1163/221058707X00549

- Pedersen, Olaf (2011), A Survey of the Almagest, Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, New York / Dordrecht / Heidelberg / London: Springer Science + Business Media, ISBN 978-0-387-84825-9

- Mackenzie (1915). "13 Astrology and Astronomy". Myths of Babylonia and Assyria.

- Pinches, Thophilus G. "5". The Religion of Babylonia and Assyria. Archived from the original on 17 December 2007.

- David N. Talbott (1980). The Saturn Myth. Garden City, New York, USA: Knopf Doubleday & Company, Inc. p. 419. ISBN 0-385-11376-5. Retrieved 2013-01-03.

- Neugebauer, Otto (1975). A history of ancient mathematical astronomy. pp. 788–789.

- Neugebauer, Otto; Van Hoesen, H. B. (1987). Greek Horoscopes. pp. 1, 159, 163.

- Jones, Alexander (1999). Astronomical papyri from Oxyrhynchus. pp. 62–63.

It is now possible to trace the medieval symbols for at least four of the five planets to forms that occur in some of the latest papyrus horoscopes ([ P.Oxy. ] 4272, 4274, 4275 [...]). That for Jupiter is an obvious monogram derived from the initial letter of the Greek name. Saturn's has a similar derivation [...] but underwent simplification. The ideal form of Mars' symbol is uncertain, and perhaps not related to the later circle with an arrow through it. Mercury's is a stylized caduceus.

- "Bianchini's planisphere". Florence, Italy: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza (Institute and Museum of the History of Science). Retrieved 2010-03-17.

- Maunder, A. S. D. (1934). "The origin of the symbols of the planets". The Observatory. 57: 238–247. Bibcode:1934Obs....57..238M.

- Vigfússon (1874:456).

- Philip Ball, The Devil's Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science, ISBN 978-0-09-945787-9

- 中国古代的日月五星 Archived 2010-05-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Sky Publishing – Latitude Is Everything