Clatchard Craig

The fort of Clatchard Craig was located on a hill of the same name by the Tay. A human presence on the site has been identified from the neolithic period onward and the fort itself was occupied from the sixth century AD until at least the eighth century.[1] It stood close to several places which were centres of secular and religious power during the early Middle Ages including Abernethy,[2] Forteviot,[3][4] Scone and Moncreiffe.[5] As such it seems to have been an important stronghold of the Picts.

An aerial photograph of Clatchard Craig taken in 1932. (Royal Air Force) | |

| Location | Newburgh |

|---|---|

| Region | Fife |

| Coordinates | 56.3463°N 3.2252°W |

| Type | Pictish hill fort |

| History | |

| Builder | Picts |

| Material | Timber faced earth and stone |

| Periods | Neolithic Bronze age Iron age Roman Pictish |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1954–55 1959–60 |

| Condition | Destroyed by quarrying |

In the late twentieth century AD Clatchard Craig was entirely destroyed by quarrying for aggregate authorised by the British Ministry of Transport.[6] The former site of the fort, now privately owned,[7] remains a quarry.

Location of the Fort

The fort of Clatchard Craig was situated on a hill of 119m height overlooking the coastal plain of the Tay. The town of Newburgh, founded during the Middle Ages, now occupies the land between the site of the fort and the river.[6] The fort stood on the western side of the mouth of a valley which led South to central Fife. The eastern side of the valley-mouth was occupied by the peak of 'Mare's Craig' which produced several ancient artefacts but was never excavated.[8] 'Mare's Craig' was also destroyed by quarrying during the twentieth century. A single-walled fort known as 'Black Cairn Hill' is situated to the south-west of the former Clatchard Craig and is still largely intact.[9]

History Before Excavation

The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland interprets the name of Clatchard Craig as deriving from the Gaelic elements 'clach', 'ard' and 'creag', or 'stone', 'high' and 'crag' respectively.[6] This interpretation is supported by the fact that the hill of Clatchard Craig once held a freestanding pillar of stone, 27m high, which was demolished in 1846 during the construction of The Edinburgh and Northern Railway.[6]

The first known reference to the site is in a manuscript of the early seventeenth century by James Balfour of Denmilne. While discussing his home of Denmylne Castle he wrote:

hard adjoyning to it is thair a great rock on the tope of the wche stuid thair a strange castell double trinshed leueiled with the ground by Martius Commander of the Thracian Choorts under the emperour Commodus. The ruine of thes Trinches may to this day be perceiued.[6]

Balfour provided no justification for his claim that the fort was destroyed by Roman forces. Clatchard was subsequently mentioned by Robert Sibbald in 1711 who attributed its construction to the Romans.[6] Clatchard Craig lay close to the authentic Roman site of Carpow, a legionary fortress of the Severan era.[10]

Quarrying in the area began with the arrival of the railway and, due to the hill's valuable andesite geology, which provided raw material for the building of roads and railways, the excavations continued.[6] As the quarry approached the perimeter of the fort the British Ministry of Works conducted two rescue excavations in 1954–55 and 1959–60 intended to investigate the site before its destruction.[6] Between the two World Wars the British Ministry of Works petitioned for an end to the quarrying but was over-ruled by the Ministry of Transport. The quarrying then continued unchallenged.[6]

Archeological Excavations

The two excavations of Clatchard Craig, with other archaeological discoveries, allow an outline of the site's history to be described.[1][6] The earliest signs of human activity on the site were pottery fragments and a petrosphere both dating to the neolithic period.[1][6] Continued occupation during the Bronze Age was indicated by the discovery of a cist burial and fragments of pottery identified with the beaker culture.[1][6]

Iron-Age occupation attested by a scatter of pottery in both upper and lower enclosures. During the Roman era the site continued to be used. A rotary quern, iron-age pottery and fragments of Samian ware were identified.[1][6] However, few of these artefacts dated to the second and third centuries AD, when Rome was very active in central Scotland. During these centuries the Antonine Wall was occupied and Septimius Severus led a campaign in the area between 208 and 211 AD. The nearby Roman fortress of Carpow was constructed under Severus.[10]

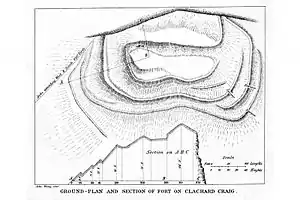

The first evidence of permanent structures on Clatchard Craig date to the Dark Ages. While occupied as a fortress, it consisted of a series of six ramparts surrounding a building on the summit of the hill.[1] It comprised three main structural phases, the latest being the sub-rectangular enclosure on top, which measured 230 feet (70 m) by c. 115 feet (35 m), from which relics of early medieval date were obtained. This stood within a heavy oval rampart, 330 feet (100 m) by 200 feet (61 m). The next rampart overlay a series of hearths in which pottery was found, and in this rampart were masonry blocks with adherent mortar in which were fragments of tile. The third rampart, like the two preceding, was timber-laced, later replaced by earth and stone. There were a further two ramparts with minor additions and supplementary features. The earliest two ramparts, built in timber-laced stone were dated to the sixth century AD by radiocarbon dating. Construction of the ramparts continued throughout the era with pieces of recycled Roman tile and mortared masonry included in the fabric.[1][6] The fort's walls were vitrified at some point suggesting that the site had once been destroyed by fire. A date cannot be ascribed to either the burning of the fort nor its abandonment.[1][6]

The presence of a paved hearth on the summit of the fort indicated a residence of high status while the discovery of clay moulds for the casting of pennanular brooches showed that elite craftsmen worked within the fort. The impression that the fort was a high-status site was reinforced by the discovery of an ingot of silver[1][6] and by the presence of fine metalworking activity within its perimeter.[1]

References

- The site record for Clatchard Craig at RCAHMS

- The Monuments of Abernethy at RCAHMS

- A discussion of Pictish Forteviot

- Current Archeological Excavations at Forteviot

- Moncrieffe Hill at RCAHMS

- Excavation Summary by the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

- Breedon Aggregates Limited.

- Mare's Craig at RCAHMS.

- Site record of Black Cairn Hill at RCAHMS

- Site record of Carpow at RCAHMS