Coast Salish people and salmon

The Coast Salish people of the Canadian Pacific coast depend on salmon as a staple food source, as they have done for thousands of years. Salmon has also served as a source of wealth and trade and is deeply embedded in their culture, identity, and existence as First Nations people of Canada.[1] Traditional fishing is deeply tied to Coast Salish culture and salmon were seen "as gift-bearing relatives, and were treated with great respect" since all living things were once people according to traditional Coast Salish beliefs.[1] Salmon are seen by the Coast Salish peoples are beings similar to people but spiritually superior.

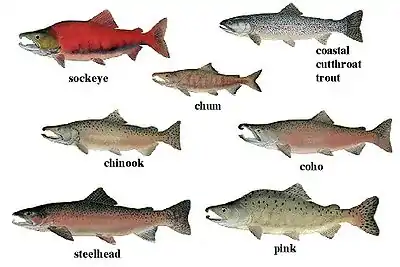

The fishing methods employed fall under the category of artisanal fishing. They employ low-technology, traditional fishing techniques like net-fishing, stone-fishing and weir fishing. The five species of Pacific salmon found in British Columbia waters are Sockeye, Pink, Chum, Coho, and Chinook.

Salmon

For thousands of years, long before colonization, Coast Salish people have depended on salmon as a staple food source as well as sources for wealth and trade. Salmon is deeply embedded in their culture, identity, and existence as First Nations people of Canada.[1] The five species of Pacific salmon found in waters of British Columbia are Sockeye, Pink, Chum, Coho, and Chinook. They are commonly found in the Fraser, Skeena, Nass, Somass, Thompson, and Adams rivers.[2]

Diet

During the winter months, salmon is a main food that provide many sources of nutrients for the Coast Salish people. Salmon is preserved by drying, smoking, canning or freezing the fish.[3] In the Fraser Canyon during the summer months, salmon is hung on racks placed on rock bluff and wind dried. Whereas smoked salmon is hung on poles and racks inside a smoke house for a few days. Alternatively, salmon can also be preserved by canning, where it is cut up into pieces, washed, salted, and then canned. Salmon can be eaten in many different ways such as roasted, boiled, or steamed. To roast it, salmon are placed on stakes around a fire and often eaten as snacks. Boiled and steamed salmon occur in bentwood boxes or open pits.[4]

Cultural significance

Traditionally fishing is deeply tied to Coast Salish culture and salmon were seen "as gift-bearing relatives, and were treated with great respect" since all living things were once people according to traditional Coast Salish beliefs.[1] Salmon are seen by the Coast Salish peoples are beings similar to people but spiritually superior.[5] This relation of respect and reciprocity with salmon translated into rituals of cultural significance such as the First Salmon ceremony:

It was believed that the runs of salmon were lineages, and if some were allowed to return to their home rivers, then those lineages would always continue. The WSÁNEC (Saanich people) believe that all living things were once people, and they are respected as such. The salmon are our relatives. ... Out of respect, when the first large sockeye was caught, a First Salmon Ceremony was conducted. This was the WSÁNEC way to greet and welcome the king of all salmon. The celebration would likely last up to ten days. ... Taking time to celebrate allowed for a major portion of the salmon stocks to return to their rivers to spawn, and to sustain those lineages or stocks[6]

This system is maintained through cultural practices which also ensures the sustainment of fishing populations. For example, "the potlatch functioned as a 'monitoring device' through which the sustainability of a title-holder’s fishing practices was repeatedly assessed by members of the tribes who potlatched together".[1]

Decisions about the timing, location, methods and quantity of fishing harvests were made to by community elders with deep knowledge of salmon fishing.[7] Fishing was not a distinct occupation but was instead integrated to the cultural laws of these communities.[1]

The arrival of canning technologies and commercial fishing industries the fishing practices of Coast Salish people were severely marginalized and altered. They could no longer fish without licenses and became wage workers . " Cannery operators considered Indigenous people to be at most "helpers" in the industrial fishery. As "helpers," they were paid only for their labour, and not for the sale of their resources".[8]

The salmon is also presented as a cultural symbol for Coast Salish people in Totem poles, canoes and oars. In Totem Poles it is present as a symbol of life, abundance, prosperity and nourishment.[9] It is also represents dependability and the renewing cycle of life, through its death the salmon sustains many other beings and still returns every year providing sustenance for humans and other animals.[9]

Ancestrally it is believed that in order for the salmon to return in abundance the following year, it has to be killed and disposed following certain ancestral guidelines. If these procedures are followed then the salmon will return in abundance and the reciprocal relationship will endure.[5]

Amongst the Kwak'waka'wakw a traditional ceremony celebrated the salmon spirits by donning individuals with salmon masks that symbolize the power of the salmon. They leap and dance with this masks like the salmon, leaps and swims against the river's current.[5] This ceremony takes them on a spiritual journey "undersea world of the salmon people where they in-spirit their relationship with and dependence" on salmon.[5] The salmon spirits respond by sending abundant salmon upstream for prosperous harvests.[5]

Salmon are at the base of many First Nations culture. There are songs, dances, visual arts and legends based on the lives of salmon. First Nations of B.C., including Bella Coola, Nootka, Tlingit and others, rely on salmon as a primary source of subsistence before the salmon population began declining.

Fishing methods

The fishing practices and methods of the Coast Salish remain tied to the salmon as a cultural symbol and a source of respect. They fall under the category of artisanal fishing. They employ low-technology, traditional fishing techniques like net-fishing, stone-fishing and weir fishing.

These techniques are common and found throughout the world in many different fishing communities, but the Coast Salish First Nations people employed this method in a slightly different way: "At the end of the net, a ring of willow was woven into the net, which allowed some salmon to escape".[6] This was done in order to help with conservation of salmon, and out of respect for the animal.

Some communities on Vancouver Island place willow and cedar nets in locations like the mouth of a bay in a perpendicular position to the shore. This way the flow and current of the river drove the salmon easily into their nets.

Stone fishing consists of building "an arc of carefully positioned stones that created shallow pools from which salmon could be selectively harvested by waiting fishers".[10] Then at moments of low tide the salmon were easily fished out of the stone traps and harvested.

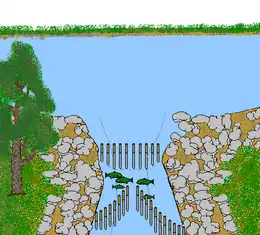

One of the other fishing methods employed by the Coast Salish First Nation people is weir fishing. Weirs are barriers placed across rivers. In this case they are made of wood and are used for fishing. "On relatively shallow, slow-moving tributaries, weirs were used to channel fish into traps, or towards fishers with other harvesting equipment. These fence-like structures often had panels that could be removed when not fishing, and had complex underwater channels and impounding pens".[11]

Weir fishing remains a controversial method since it is argued, often by canneries, that these barriers impeded salmon from reaching their spawning grounds. Weir fishing is deemed illegal by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). However, it is argued by some that weir fishing may actually help in the conservation of salmon. "Some environmentalists today are looking to weirs and other stationary traps as examples of selective harvesting techniques that could help conserve endangered salmon populations".[1]

Although they traditionally considered as Artisanal fishing, the methods used by the Coast Salish do not operate at a low scale level. It is estimated that "between 4 million and 12 million salmon would have been consumed annually, and this does not include fish harvested for trade, or for ceremonial purposes".[12] The organization and sustainment of this fishing system was maintained through careful regulation of " timing and level of harvest".[13]

Legislation and policies

Fishing regulations

Many First Nations' communities have conducted their traditional fisheries through special harvesting practices and methods that have successfully sustained these salmon fisheries without the intervention of the Canadian government. Regulation was done by leaders of house groups who coordinated who, when, and how one could fish. The leader was someone who is responsible for the fishing grounds and resources were carefully regulated based on their background knowledge of the extended family, various fishing methods, capacity of dry rack, capacity of camps, number of children in extended families, and number of fishing rocks accessible. Slowly this is being replaced with government regulations and licenses that restrict First Nations and their access to fisheries and salmon which has led to great tension and conflict between the First Nations and non-indigenous fishermen.[1]

1877: Use of weirs for fishing is outlawed.

1880: The Aboriginal Food Fishery was created. This restricted First Nation fishing for food only which to benefit and expand on commercial fishing.[1]

1888: Regulation prohibiting fishing by "means of nets or other apparatus without leases or licenses from the Minister of Marine and Fisheries". Also indicating that "Indians shall, at all times, have liberty to fish for the purpose of providing food for themselves but not for sale, barter or traffic, by any means of other with drift nets or spearing.[1]

1894: The Fishing Regulation Act was amended. Government officials required Aboriginals to acquire a permit to fish for food.[14][15]

1917: New amendment that food fishing permits would be subject to the same closed seasons, area, and gear restriction as the non-Native commercial fishery.[16]

1992: Aboriginal Fisheries strategy: Launched by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to provide stable fishery management after the Supreme Court of Canada ruling for Sparrow, Van der Peet. The decision found that Musqueam First Nation has an aboriginal right to fish for food, social, and ceremonial purposes, taking priority, after conservation, over other uses of the resource, and the importance of consulting with aboriginal groups when their fishing rights might be affected.[17]

1994: The Allocation Transfer Program (ATP) was created with operating mandate of $4 million. Since this program, 87 community commercial licences have been issued to aboriginal groups.[18]

1996: Federal Fisheries Minister Fred Mifflin announced the Pacific Salmon Revitalization Strategy. Involved an $80 million DFO-funded voluntary licence retirement program.[18]

1998: Establishment of the Pacific Fisheries Adjustment and Restructuring Program (PFAR). This $200 million program allowed commercial licence holders to voluntary relinquish the licences and money were distributed to assist in more selective techniques, habitat restoration, and stewardship projects.[18]

Fishing licences

As the number of non-indigenous fishers increased, more regulations and laws were imposed on the fisheries leading to the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulation of 1993. Whereas Coast Salish people had been free to fish when and where they needed, from then on they had to seek fishing licences from the government. Many refused to give up their fishers or buy fisheries licenses and even insisted that the money for the licences belonged to them.[19]

In 1890s, only 40 indigenous fishers on the Fraser had licenses that allowed them to catch fish independently from canneries. In 1912, a policy termed "bona fide white fishermen" gave priority to non-indigenous people of the North Coast.[20] As well many were denied fishing license due to pressure from the cannery owners. Access to seine licences weren't available to First Nation fishers until 1924, when most non-native fishers have already obtained theirs.[1]

Though the government has established treaty rights for Coast Salish people to fish for food, it is still greatly regulated by Department of Fisheries and Oceans with restrictions as to what kind of gear can be used, the hours and days during which gear can be deployed, and the particular species that may be targeted.[1]

References

- "Aboriginal Fisheries in British Columbia". indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- Groot, C. and L. Margolis. 1991. Pacific Salmon Life Histories. Vancouver, UBC Press.

- Johnson, Suzanne (August 26, 2014). "First Nations Traditional Foods Fact Sheet" (PDF). First Nations Health Authority. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "Technology - Fish Processing Techniques: First Nations". bcheritage.ca. Archived from the original on 2012-12-26. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- Crawford, S. J. (2007). Native American Religious Traditions. Retrieved from in canoes coast salish&source=bl&ots=5jQiogqp6R&sig=VuekB3DYEot-UZfmH53hRlK3nSk&hl=es-419&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj36ubU8fjLAhVDj5QKHUDkC1oQ6AEIWjAM#v=onepage&q=salmon in canoes coast salish&f=false

- Nicholas Xumthoult Claxton, " ISTÁ SĆIÁNEW, ISTÁ SXOLE: ‘To Fish as Formerly:’ The Douglas Treaties and the WSÁNEĆ Reef-Net Fisheries." In Lighting the Eighth Fire: The Liberation, Resurgence, and Protection of Indigenous Nations, ed. Leanne Simpson. Winnipeg, Arbeiter Ring, 2008. 54-55.

- Naxaxalhts’i, Albert (Sonny) McHalsie, "We Have to Take Care of Everything That Belongs to Us," in Be of Good Mind: Essays on the Coast Salish, ed. Bruce G. Miller. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2007. 97-98.

- Newell, Tangled Webs, 53, 77.

- Squamish Lil'wat Cultural Centre. (n.d.). ANIMAL SYMBOLOGY. Retrieved April 05, 2016, from http://shop.slcc.ca/node/5

- Charles Menzies and Caroline Butler, "Returning to Selective Fishing Through Indigenous Fishing Knowledge,"American Indian Quarterly 31, 3 (2007): 451-452.

- Keith Thor Carlson, "History Wars: Considering Contemporary Fishing Site Disputes," in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001. 58.

- David A. Smith, "Salmon Populations and the Sto:lo Fishery," in A Sto:lo Coast Salish Historical Atlas, ed. Keith Thor Carlson. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2001. 120.

- Douglas Harris, Fish Law and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001. 96.

- Harris, Douglas. Fish Law and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001.

- Landing Native Fisheries: Indian Reserves & Fishing Rights in British Columbia, 1849-1925. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2008.

- Newell, Dianne. Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 1994

- Branch, Government of Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Communications. "Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy". www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- Kerri Garner and Ben Parfitt (April 2006). "First Nations, Salmon Fisheries and the Rising Importance of Conservation" (PDF). Report to the Pacific Fisheries Resource Conservation Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 16, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- Harris, Douglas C.; Millerd, Peter (2010-01-06). "Food Fish, Commercial Fish, and Fish to Support a Moderate Livelihood: Characterizing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights to Canadian Fisheries". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 1594272. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Newell, Dianne. Tangled Webs of History: Indians and the Law in Canada’s Pacific Coast Fisheries (Toronto: University of Toronto Press), 1994.

External links

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans

- Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulation

- Aboriginal Fisheries strategy

- Supreme Court of Canada ruling for Sparrow, Van der Peet

- Vancouver Aquarium

- First Nations Traditional Foods Fact Sheets

- Report on First Nations, Salmon, Fisheries, and the Rising Importance of Conservation

- Food Fish, Commercial Fish, and Fish to Support a Moderate Livelihood: Characterizing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights to Canadian Fisheries, By: Douglas C. Harris