Common potoo

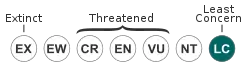

The common potoo, or poor-me-ones (Nyctibius griseus), is one of seven species within the genus potoo.[2] It is notable for its large yellow eyes and comically wide mouth. Potoos are nocturnal near passerines related to nightjars and frogmouths. They lack the characteristic bristles around the mouths of true nightjars.[3] Until recently, the common potoo was said to range from Mexico down to the lowlands of central South America. However, in 2016, the species was subdivided into the northern potoo and the continuing branch of the common potoo, which only retains residence from Nicaragua to northern Argentina and Uruguay.[2] This division was largely based on the differing calls of the two species (view 0:39-0:50 here). Though not yet classified as endangered, the common potoo has been declining in numbers due to habitat destruction.[2]

| Common potoo | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Common Potoo spotted in Alto Verá, Itapúa, Paraguay | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Caprimulgiformes |

| Family: | Nyctibiidae |

| Genus: | Nyctibius |

| Species: | N. griseus |

| Binomial name | |

| Nyctibius griseus (Gmelin, 1789) | |

| |

Description

Common potoos are 34–38 cm long with molted red-brown, white, black, and grey cryptic plumage.[4] This disruptive coloration allows the potoo to camouflage into branches.[5] The sexes appear similar, and cannot be distinguished upon observation.[6] The eyes can appear as giant black dots with a small yellow ring, or as giant yellow irises with small pupils due to voluntary pupil constriction.[6] The potoo has two to three slits in the eyelid so that it can see when the eyelids are closed; these notches are always open. The upper and lower eyelids can be moved independently and rotated so that the bird may adjust its field of vision.[6] The common potoo has an unusually wide mouth with a tooth in its upper mandible for foraging purposes.[7]

Distribution and habitat

The common potoo is a resident breeder in open woodlands and savannah.[2] It avoids cooler montane regions; it is rarely observed over 1,900 meters ASL even in the hottest parts of its range. It tends to avoid arid regions, but was recorded in the dry Caribbean plain of Colombia in April 1999. It has many populations in the gallery forest-type environment around the Uruguayan-Brazilian border. A bit further south, where the amount of wood-versus grassland is somewhat lower, it is decidedly rare, and due west, in the Entre Ríos Province of Argentina with its abundant riparian forest it is likewise not common. The birds at the southern end of their range may migrate short distances northwards in winter.[8]

Feeding

This nocturnal insectivore hunts from a perch like a shrike or flycatcher. It uses its wide mouth to capture insects such as flies and moths. It has a unique tooth in its upper mandible to assist in foraging, but swallows its prey whole.[7]

Behavior

Vocalization

The common potoo can be located at night by the reflection of light from its eyes as it sits on a post, or by its haunting melancholic song, a BO-OU, BO-ou, bo-ou, bo-ou, bo-ou, bo-ou, bo-ou, bo-ou dropping in both pitch and volume. When seized, this bird produces a squeaky sound not unlike that of a crow.[9] This call greatly differs from that of much deeper and more dramatic northern potoo (view 0:39-0:50 here) .

Cryptic behavior

The common potoo seeks to mimic the perch it rests on, utilizing a technique called masquerading. Adult and juvenile potoos alike will choose perches that are similar in diameter to their own bodies, so that they will better blend in with the stump.[10] The majority of potoos will choose stumps and other natural materials to rest on, but some adults have been spotted perching on man-made items. These birds adjust their perching angle to best mimic the stump they are on.[10]

Potoos sit with their eyes open and their bill horizontal while awake, but if disturbed they will assume an alert “freezing” posture (flexibility). This entails sticking the beak vertically up in the air, closing the eyelids (of which they can still see through via slits), and remaining still.[6] If disturbed by larger animals, such as common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus), it may break its camouflage and try to chase them away.[11] If disturbed by a human being, their behaviors can be quite variable: quickly flying away, intimidation via beak-opening, or remaining still even when being touched.

Nesting choice and maintenance

The common potoo will choose a stump 3–15 meters high to occupy.[12] It will normally choose a branch stump as a nest, and add no sort of decorative or insulate material. It will eject feces from its perch to keep the nest clean.[6] If breeding, the potoo will choose a stump with a small divot where an egg can be laid.[13]

Reproduction

Mating and brooding

Common potoos are monogamous.[14] After mating, the female will lay a single white egg with lilac spots directly into the depression in a tree limb.[15][13] Parents will normally care for one egg at a time. The male and female alternate sitting on the egg while the other forages for insects. They will divide brooding time evenly.[4]

Juvenile development and fledging

Potoos lay their eggs in December to begin their approximately 51 day nesting period, one of the longest nesting periods for birds their size.[12] Young potoos hatch after about 33 days, using their egg tooth to break free and emerge as downy individuals with pale brown and white stripes.[12][10] The hatchling is fed by regurgitation. Parents will gradually decrease their presence in the nest with the juvenile as it matures. While the parents are away from the nest, the fledgeling will begin to feed on nearby flies and preen itself.[10] At around 14 days, the juvenile will begin wing exercises, and take gradual steps toward leaving the nest. It will venture out on several flights, then return to the nest with its parents, before departing for good about 25 days after hatching.[12] Juveniles display disruptive coloration like the adult, so they can also camouflage into a branch, as shown on the right.[5] Apart from flying away, chicks respond to disturbances in a similar manner to adults.[12]

Footnotes

- BirdLife International (2012). "Nyctibius griseus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Common Potoo". American Bird Conservancy. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Booth, Rosemary J. (2015), "Caprimulgiformes (Nightjars and Allies)", Fowler's Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Volume 8, Elsevier, pp. 199–205, ISBN 978-1-4557-7397-8, retrieved 3 October 2020

- Praimsingh, Sangeeta (2015). "Nyctibius griseus (Common Potoo)" (PDF). The Online Guide to the Animals of Trinidad and Tobago.

- Cott, Hugh (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Oxford University Press. pp. 352–353

- Borerro, Jose Ignacio (1974). "Notes on the Structure of the Upper Eyelid of Potoos (Nyctibius)". The Condor. 76 (2): 210. doi:10.2307/1366732. ISSN 0010-5422.

- Hilty, Steven L. (2003). Birds of Venezuela. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3409-9. OCLC 649913131.

- Cuervo et al. (2003), Strewe & Navarro (2004), Azpiroz & Menéndez (2008)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFdQFG3LbGo (The man seizing it is in fact trying to unentangle the bird from some wire.)

- Cestari, César; Gonçalves, Cristina S.; Sazima, Ivan (2018). "Use flexibility of perch types by the branch-camouflaged Common Potoo (Nyctibius griseus): why this bird may occasionally dare to perch on artificial substrates". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 130 (1): 191–199. doi:10.1676/16-175.1. ISSN 1559-4491.

- de Lyra-Neves et al. (2007)

- Skutch, A. F. 1970. Life history of the Common Potoo. Living Bird 9:265-280

- E.g. of Cecropia: Greeney et al. (2004)

- Cooper, Robert J. (April 2004). "Nightjars and Their Allies: The Caprimulgiformes David T. Holyoak". The Auk. 121 (2): 622–623. doi:10.2307/4090427. ISSN 0004-8038.

- Hilty, Steven L.; Brown, Bill (1986). A Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-691-08372-8.

References

- Azpiroz, Adrián B. & Menéndez, José L. (2008): Three new species and novel distributional data for birds in Uruguay. Bull. B.O.C. 128(1): 38–56.

- Common Potoo. (2019, January 17). Retrieved October 3, 2020, from https://abcbirds.org/bird/common-potoo/

- Cuervo, Andrés M.; Stiles, F. Gary; Cadena, Carlos Daniel; Toro, Juan Lázaro & Londoño, Gustavo A. (2003): New and noteworthy bird records from the northern sector of the Western Andes of Colombia. Bull. B. O. C. 123(1): 7–24. PDF fulltext

- de Lyra-Neves, Rachel M.; Oliveira, Maria A.B.; Telino-Júnior,Wallace R. & dos Santos, Ednilza M. (2007): Comportamentos interespecíficos entre Callithrix jacchus (Linnaeus) (Primates, Callitrichidae) e algumas aves de Mata Atlântica, Pernambuco, Brasil [Interspecific behaviour between Callithrix jacchus (Linnaeus) (Callitrichidae, Primates) and some birds of the Atlantic forest, Pernanbuco State, Brazil]. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 24(3): 709–716 [Portuguese with English abstract]. doi:10.1590/S0101-81752007000300022 PDF fulltext.

- Greeney, Harold F.; Gelis, Rudolphe A. & White, Richard (2004): Notes on breeding birds from an Ecuadorian lowland forest. Bull. B.O.C. 124(1): 28–37. PDF fulltext

- Strewe, Ralf & Navarro, Cristobal (2004): New and noteworthy records of birds from the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta region, north-eastern Colombia. Bull. B.O.C. 124(1): 38–51.

Further reading

- ffrench, Richard; O'Neill, John Patton & Eckelberry, Don R. (1991): A guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago (2nd edition). Comstock Publishing, Ithaca, N.Y.. ISBN 0-8014-9792-2

- Hilty, Steven L. (2003): Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5

External links

- Common potoo videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- "Common potoo" photo gallery VIREO