Constantin Dobrescu-Argeș

Constantin I. Dobrescu, better known as Dobrescu-Argeș (June 28, 1856 – December 10, 1903), was a Romanian peasant activist and politician, also active as a teacher, journalist, and jurist. Active from his native Mușătești, in Argeș County, he established a regional, and finally national, base for agrarian politics. He is considered Romania's second agrarianist, after Ion Ionescu de la Brad, and, with Dincă Schileru, a revivalist of the peasant cause in the Romanian Kingdom era. Dobrescu was notoriously unpersuaded by agrarian socialism, preferring a mixture of communalism and Romanian nationalism, with some echoes of conservatism. Thus, he stopped short of advocating land reform, focusing his battles on democratization through universal suffrage, and on obtaining state support for the cooperative movement. He himself founded some of the Kingdom's first cooperatives, also setting up model schools, the first rural theater, and the first village printing press—which put out his various periodicals.

Constantin I. Dobrescu-Argeș | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) Bust of Dobrescu in Curtea de Argeș, by Frederic Storck. | |

| Member of the Romanian Assembly of Deputies | |

| In office 1889–1898 | |

| Constituency | Argeș County |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 28, 1856 Mușătești, Wallachia |

| Died | December 10, 1903 (aged 47) Mușătești, Kingdom of Romania |

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Political party | Peasants' Committee (1881–1888) Conservative Party (1888) Radical Party (1889) League of Universal Suffrage (1894) Partida Țărănească (1894–1899) |

| Relations | Alexandru Valescu (brother-in-law) |

| Profession | Schoolteacher, jurist, activist, cooperative organizer, playwright |

Although well liked by cultural and political figures of all hues, with whom he collaborated on various projects, Dobrescu's clandestine support for the concept "Greater Romania" made him a political liability. Technicalities were invoked to block him out of the Assembly of Deputies, despite his repeatedly winning in elections. Eventually, he served four contiguous terms in the 1880s and '90s, moving from alliances with the Conservative and Radical Parties to the position of an isolated independent, and, in 1895, to leader of his own Partida Țărănească ("Peasants' Party").

Dobrescu's nationalism and his association with ill-reputed figures such as Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești contributed to his marginalization, as did his reputation as a "carnival peasant", one who had backstage dealings with the establishment. Such ridicule and one public beating closely preceded scandals involving his financial misdeeds, alleged or proven. Upon the end of a publicized trial lasting to 1903, Dobrescu was found guilty of fraud, and emerged from prison after three months with his health compromised, dying in his peasant home. He remained cited as a martyr and precursor of agrarian and Poporanist movements, revived during the interwar. He was also credited as a forerunner of the National Peasants' Party.

Biography

Beginnings

Born in Mușătești, his father Ion Dobrescu was a Romanian Orthodox priest.[1][2] The family ancestors included Pitar Nicolae Popescu, who had fought in the Wallachian uprising of 1821, becoming secretary to its leader, Tudor Vladimirescu; Vladimirescu would serve as an inspiration to Dobrescu in his own efforts of social improvement.[3] A grandfather, Toma, also credited as an influence on the young Dobrescu, had participated in the 1848 Revolution and had gone into hiding upon its defeat.[4] Additionally, Dobrescu was much inspired by the political articles of Mihai Eminescu, which he also read out, and put into more accessible language, for his peasant constituents.[5]

After attending primary school in his native village, where he used dirt and his own fingers as writing utensils,[6] Dobrescu continued his education at Curtea de Argeș and Pitești. He studied at the theological seminary in the former town, one of several peasant inductees.[7] In 1874 or 1875, he became a teacher in Mușătești.[1][7] During this period, he became interested in the cause of peasant representation, militating against the weighted suffrage established under the Constitution of 1866, and implicitly against the two-party system that it favored. As he put it, the peasant could have "an active part, of the uttermost importance".[8] He challenged the political establishment by noting that peasant representation had steadily declined, from 36 deputies in the ad-hoc Divans to 33 in the "United Principalities" era, and then to none in the Assembly of Deputies.[9]

As noted by the agrarianist writer Ilariu Dobridor, Dobrescu was the second person in Romanian history, after Ion Ionescu de la Brad, to have championed peasantism as a political, not merely "philanthropic", effort.[10] Also according to Dobridor, Dobrescu's first attempts to set up an agrarian movement brought him into contact with left-wing figures such as Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești and Constantin Mille—both disappointed him.[11] He put himself up as a candidate in the legislative election of 1879, winning an Assembly seat for the Fourth College in Argeș. However, the electoral law specified that he had to be aged 25 to qualify, and so his mandate was invalidated.[12] The elections did produce one peasant deputy, Dincă Schileru (Schileriu), who affiliated with the Radical Party of C. A. Rosetti and George Panu. He served almost continuously to 1911.[13]

Dobrescu's other work was focused on cultural activism, for the goal of creating and popularizing "rural dramas, rural comedies, rural poetry, [...] our own philosophy, our own arts, purpose, traditions and our own sort of civilization".[8] In order to facilitate the peasantry's access to education and the amenities of modern life, Dobrescu also advocated for the establishment of free libraries, rural banks and general stores. In 1879, the Central Rural Athenaeum, devoted to teaching adult peasants to read and write, was founded under his guidance. This institution comprised a choral and folk dance ensemble, a public library, an ethnographic and pedagogic museum, an agronomical station, a gymnastics arena, a school for adults, several cultural circles, a popular bank and a magazine that disseminated news of these venues' achievements.[1] In 1882, Dobrescu also created the first rural theater in the entire Romanian Kingdom.[14] This was followed in 1884 by the country's first cooperative, set up at Domnești under the name of Frăția ("Brotherhood")—although Mușătești remained the hub for the cooperative movement for the next two decades.[8]

In order to better organize for his struggle, in 1881 Dobrescu founded at Mușătești a Peasants' Committee, a political network that brought together activists from Argeș and Gorj, later expanded into other regions of Muntenia and Oltenia. Its co-leaders were Schileru and Mucenic Dinescu, and its first congress was held at Corbeni in August 1882.[15] According to Dobridor, this was a historic moment, bringing together peasants who had hitherto been separated by sectarian causes. Dobrescu "simply lifted up his sword to sever the ropes of coterie that had penetrated the very soul of the peasants, had carved the mark of slavery into their napes, like a yoke carving into the neck of a buffalo."[16]

Early political work

An ardent nationalist and "irredentist", Dobrescu also supported the clandestine activities of Romanians in Transylvania and other parts of Austria-Hungary. These brought him to the attention of Ion Brătianu, doyen of the National Liberal Party and Argeș-based squire, who wanted to preserve good relations with the Austrian establishment and civil peace in his constituency. Dobrescu was secretly investigated by a Captain Vinieru, who reported from Sălătrucu that Dobrescu was coordinating illegal activities over the frontier, and had himself traveled to the area around Rothenturm for unknown purposes.[17]

The Vinieru episode came shortly after the democratization reforms initiated by Brătianu, which had increased representation for the middle classes, rural ones included, and merged the lower two electoral colleges into a Third. Such enfranchisement came with its own limitations: some 98% of the electorate could only vote for Assembly with indirect suffrage, the rest being excluded from this by wealth and literacy requirements; some 41% of the deputies elected under these new laws represented rural constituencies, but most of them were not land-working peasants.[18] By Dobrescu's own calculations, there was still a 1:20,000 ratio of representation in the new college, whereas the upper two had 1:180 and 1:421, respectively.[19]

Belonging to an intermediary class, Dobrescu himself returned as a peasant candidate elections of that year, winning a seat for Argeș's Third College. He was again invalidated, since, as a teacher, he had a conflict of interest.[12] He ran again in by-elections, and, although he had suspended his work in state education, was again faced with invalidation. This time, he was reproached for not having served in the Army,[12] but the real reason may have been his irredentist subversion.[20] At the time, Vinieru suggested that Dobrescu was involved in the June 1887 episode that ended with a shootout between an "irredentist" group and the Romanian Army, at Albești. Also according to Vinieru, the affair was kept secret by the National Liberals, and altogether ignored by the opposition Conservatives.[21]

In the October 1888 election, Dobrescu took a Third College seat at Argeș, with 491 votes from 571. He ran on a Conservative ticket—backing the government of Theodor Rosetti, and defeating the National Liberal Theodor T. Brătianu.[22] His mandate coincided with the peasant revolts of 1888, which Dobrescu anticipated in his Assembly speeches.[23] Upon the rebellion's quashing, he expressed a moderate position, refusing to condemn Rosetti for his violent response to violence, and agreeing with him on the underlying causes of rural unrest.[24] Registering as an independent, he was closely aligned with Schileru's Radicals in February 1889,[25] and is tentatively described by scholar Philip Gabriel Eidelberg as a "liberal populist".[26] In April 1889, he was listed as one of 17 Radical and dissident Liberal deputies, all of whom voted against the project to fortify Bucharest.[27]

Overall, Dobrescu argued for class collaboration "on social issues", an attitude for which he was cited approvingly by the Conservative doyen Petre P. Carp.[28] Alongside Mihai Săulescu, he drafted a bill for land reform, but later backed down from supporting it, arguing that "peasants require justice more than they require land reform". As noted by the Radical paper Lupta, it was impossible to tell whether this meant that Dobrescu was for or against land redistribution.[25] He later elaborated that what was needed were "syndicates" of state-sponsored producers, and noted that the one existing credit union only helped peasants to marginally "eke out a living".[29] By contrast, Rosetti relied on selling state land to modest producers, in lots of 5 hectares, marginalizing both the landless and wealthier peasants.[30]

This period also brought his involvement in the controversy about socialist agitation in the countryside. Dobrescu had been curious about socialism, and frequented the Marxist Ioan Nădejde. However, he soon grew to dislike both the movement and Nădejde, exposing the later as an "ass in a lion's pelt".[31] He also claimed that Nădejde had failed the test of proletarian internationalism, since, allegedly, he opposed the naturalization of Romanian Jews—possibly referring to the specific case of Ralian Samitca.[32] In turn, Mille, by then co-opted by the socialist journal Drepturile Omului, ridiculed Dobrescu as a "carnival peasant".[33] In February 1889, with fellow deputy Grigore Cozadini, Mihail Caracostea, and Ernest Sturdza, Dobrescu visited Roman County to investigate the election of Lascăr Veniamin as socialist deputy.[34] The commission's findings eventually led the other socialist deputy, Vasile Morțun, to resign and demand that he be formally tried.[35] Some of the peasants he met asked him to run for their constituency, following Veniamin's looming invalidation. Reportedly, this showed the abrupt decline of the socialist movement.[36]

Reelection and Partida Țărănească

Dobrescu also edited several periodicals: Țĕranul (1881–1884), Romania's first rural cultural and political publication; and Gazeta Poporului and Gazeta Țăranilor (1892–1903), through which he attempted to spread his ideas into the villages, aiming to integrate all rural teachers into cultural societies.[1][37][38] As noted by historian Nicolae Iorga, Gazeta Țăranilor had a "talented" editor, but a "mostly local" influence; the statement is qualified by Constantin Bacalbașa, who argues that this venue also "planted the very first seeds of a rural awakening".[39] Completed in 1894–1898 with the sheet Școala Poporului,[40] the periodicals were put out by his own printing press in Mușătești, which he had purchased with money granted by Ghenadie Petrescu, the Bishop of Argeș.[41] It was "the first printing press and bookbinder ever to have functioned in a rural commune."[42] He pursued his mission in various other ventures: pioneering institutions founded by Dobrescu during this interval include, in 1893, the cooperative in Mușătești, named after Vlad Țepeș,[43] and, in 1895, Școala Nouă ("The New School") of Domnești, furnished with a library and reading room.[1]

Before September 1890, Dobrescu had come under investigation for supposedly illegal activities also involving the artillery guards, and was shamed for this by both the left-wing daily Adevărul and the Conservative organ Timpul. They suggested that he should resign his seat, and argued that his self-promotion was distasteful.[44] Dobrescu was again elected to the Assembly, at Argeș, following the race of 1891, and reelected in 1892.[9] During these legislatures, Dobrescu listed himself as an unaffiliated "Democrat",[45] and became known as Dobrescu-Argeș to be distinguished from another Constantin Dobrescu, the National Liberal deputy of Prahova.[46] The two Dobrescus confronted each other over the issue of education reform: both agreed that Take Ionescu's Conservative project was needlessly elitist; however, Dobrescu-Argeș contended that the National Liberal counter-proposal was even more "backward". His proposal was to create a network of compulsory primary schools with equal budgets, irrespective of whether they served rural or urban communities; it failed to register support on either side of the political divide.[47]

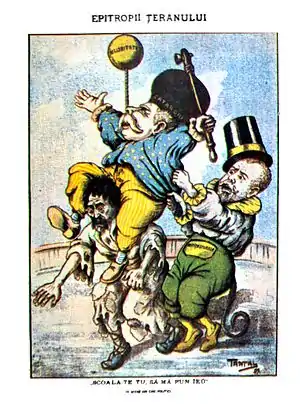

Dobrescu-Argeș's political stances were becoming ambiguous, and left-wingers came to suspect that he was secretly an ally of Lascăr Catargiu and his Conservative cabinet. Dobrescu openly supported some Conservative causes: with his theater, he performed one of his plays in front of King Carol I, who awarded him a decoration and his own portrait as a souvenir;[7] in November 1892, he voted for adding 300,000 lei to the civil list, going to the royal family.[48] A serious scandal erupted in November 1893, during debates over the establishment of an agricultural bank. Dobrescu promised nationalists A. C. Cuza and Constantin Popovici that he would endorse their amendment, excluding non-Romanians from the enterprise. He took the paper for signing, but never returned it, and found himself chased around the Assembly, threatened by Major N. Pruncu, and pummeled by Popovici.[49] The incident was witnessed by writer (and deputy) Alexandru Vlahuță, who declared himself disgusted and demoralized by the casualness of the affair.[50] Such displays prompted his 1889 rival Morțun to reuse the derisive moniker of "carnival peasant",[48] an insult later popularized by Adevărul, alongside "poisonous mushroom" and "inveterate thief".[49]

The incongruity was also noted by the Radical Panu, who argued that the "extremely congenial" Dobrescu showed up in Romanian dress but was "not a peasant, however much he may enjoy that designation [...] he merely dresses like one". He honored in Dobrescu the "intelligent man of the Argeș", noting how fast he picked up on new things, but also that he lacked discipline.[51] His abilities were also noted by the staff journalist at Foaia Populară, who described Dobrescu as the "miraculous" figure of a self-made man,[52] and by the journalist Constantin Bacalbașa, who remembered him as "highly intelligent, cultured, and overflowing with political ambitions".[53]

By March 1895, Dobrescu stood in the generic opposition, and, alongside Cuza, attacked Catargiu's cabinet, and the Conservative Party in general, for not doing enough to improve rural education. The claim enlisted a lengthy retort from the Conservative Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea, who furnished evidence for the role of upper classes in rural advancement.[54] On October 4, in Bucharest, Dobrescu held a congress that initiated a peasants' own political organization, Partida Țărănească ("Peasants' Party"). The platform, voted by peasant representatives from 20 counties, restated and detailed some of Dobrescu's main goals, including state investment into cooperatives and breeding programs, communalism with room for personal property and common land for gazing, and the auditing of peasant debt. It also had nativist requests, suggesting that peasants access a land reserve created from land repurchased by the state from non-nationals, and that leases on land be granted only by locals; an additional goal was the establishment of Greater Romania "spread as far as the Romanian language is spoken".[55] The first party of its kind in Romania, Partida operated until 1899.[1][56]

Disgrace, arrest, and death

By 1894, Dobrescu had sided with the emerging caucus of politicians favoring a switch to the universal suffrage. However, Panu and the Adevărul team, who mounted this campaign, were openly alarmed by his alleged corruption and, in 1895, obtained his withdrawal from the nascent League of Universal Suffrage. According to historian Vasile Niculae, Dobrescu was merely used by the Radicals as a "pretext allowing them to ditch any concrete action in favor of universal suffrage, and to keep the masses uninformed about [its own] blatantly pro-conservative orientation".[57] Dobrescu was returned to the Assembly a final time in 1895, after defeating the National Liberal Daniil Sterescu 645 votes to 280.[58] In the latter race, he shared a ticket with Alexandru Valescu.[59] Partida also won a seat for Muscel County, taken by M. Moisescu, with Dincă Schileru as a dissident National Liberal.[58][60]

By then, Dobrescu's party shifted some of its weight toward Muscel, with Gazeta Țăranilor printed from Câmpulung,[61] before relocating to Bucharest. According to Dobrescu, during the electoral campaign Catargiu had ordered a clampdown on the printing press in Mușătești, with authorities threatening his readers throughout the region. The editorial offices, however, remained in place.[62] Dobrescu eventually obtained a doctorate in law from the Free University of Brussels[1] after studying there from 1894 to 1897.[37] This activity sparked another controversy in 1897, upon notice that he had been awarded a scholarship by the Agriculture Ministry, then under the National Liberal Anastase Stolojan.[63]

In addition to his clashes with Catargiu, Dobrescu found himself competing with the left-wing factions of the National Liberal Party, respectively led by the Spiru Haret and Nicolae Fleva. These now fought for the peasant vote, and openly attacked the landed gentry within their own party, in particular Dimitrie Sturdza.[64] On various topical causes, Dobrescu worked with both Fleva and Haret, but also with other major figures in politics and militant culture, including Vasile Kogălniceanu, Ion Luca Caragiale, Tudor Arghezi, Nicolae Filipescu, and Take Ionescu.[1] In the 1895 legislature, he and Moisescu intervened to propose bills for universal suffrage with proportional representation, supporting and being supported by Fleva, Morțun, Kogălniceanu, Nicu Ceaur-Aslan, George A. Scorțescu, and Iuniu Lecca.[65] Nevertheless, Dobrescu was still adamantly opposed to Morțun's Marxism and the Romanian Social Democratic Workers' Party, possibly because the latter was also trying to win over peasant constituents—but also because Dobrescu respected the right of property and did not consider either an extensive land reform or collective farming.[9] According to the cultural sociologist Z. Ornea, Dobrescu and his party only offered "palliatives" to landless peasants, and as such "had no real mass basis, [were] weightless in political life."[66]

Dobrescu also found himself ignored by the establishment: in the session of March 10, 1898, his interpellation about bootlegging ended inconclusively, as most of his colleagues got up and left the Assembly hall.[67] He received some attention from Ion I. C. Brătianu, the new Minister of Public Works, who agreed with him on building a railway link between Curtea de Argeș and Câineni.[68] By then, Dobrescu had been formally indicted of falsifying an insurance policy and embezzling funds. In June, he was arrested and sent to Văcărești prison, but made bail. As reported by Filipescu's Epoca, his time in confinement was needlessly prolonged by hostile bailiffs, causing Dobrescu's mother to faint in public. However, the authorities discarded normal procedure, and left out biometrics when Dobrescu refused to comply, threatening to kill himself.[69] He pleaded his case at the Correctional Tribunal, arguing that the counterfeiting was the work of his mistress, a Ms Ionescu.[52] According to various accounts, he was being framed by the ruling class,[70] although such accusations had surfaced independently in earlier years. In 1889, the peasants of Mușătești had complained that Dobrescu, hired to legalize their land claims, had absconded with their money.[71] According to legend, Dobrescu also financed his party selling worthless bonds to peasants across the country. The scheme was only uncovered when one of his invoices showed up in a bankruptcy lawsuit.[72] He was subsequently derided by his adversaries as Dobrescu-Chitanță ("Dobrescu-Invoice").[44][46][49][73]

Dobrescu's work in public subscription also collected funds for a statue of Tudor Vladimirescu, in Târgu Jiu. He began this project in March 1895, with articles in Gazeta Țăranilor, increasingly revolutionary in tone; he also oversaw the printing of a Vladimirescu biography.[74] In 1899, as he inaugurated the statue, Dobrescu spoke about his mission of bringing about "rule of the people, by the people", "democracy in both name and fact."[3] During that year's elections, he was again in contact with the controversial candidate Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești, at Slatina. He acted as electoral agent among the peasants, promising them that Bogdan-Pitești would redistribute land from a national reserve. When his patron was defeated, the enraged peasants rioted and had to be repressed using military force.[75]

Meanwhile, his trial, in which he was represented by Fleva, came before the Ilfov County tribunal, being postponed there over the absence of witnesses.[76] Finally receiving a nine-month jail term in February 1900,[52] reduced to a three-month term in 1903, Dobrescu served his sentence at Văcărești. After being released, he was completely demoralized and soon disappeared from public life. Near the end of the same year, gravely ill and paralyzed in both legs, he was taken from Bucharest to Mușătești. He was discreetly employed by Vasile Lascăr, the Interior Minister, to review or even draft new legislation, but died in his parental home before receiving any pay.[77]

Legacy

.JPG.webp)

Sociologist Dumitru Drăghicescu suggests that, "for all we know", the "peasant issue" was introduced on the Romanian political agenda by Dobrescu. The "brilliant and likeable forerunner" directly inspired Drăghicescu to publish his own magazine for the peasants, România Rurală, which came out in 1899–1900.[78] Alexandru Valescu, who was also Dobrescu's brother-in-law, and his friend Kogălniceanu also sought to preserve the gains, and, in September 1906, reestablished Partida Țărănească.[79] Gazeta Țăranilor also continued to appear, with Valescu as publisher.[80] It accepted Kogălniceanu's leadership of the party, but maintained a Dobrescu-like stance on land reform, only favoring the renting of estates to cooperatives (rather than full redistribution among individual owners).[81]

This project blended with conservative populism through its deep association with Filipescu and the Epoca group,[82] then was altogether thwarted by the peasants' revolt of 1907, which Valescu had ominously predicted.[83] During the events, Kogălniceanu was found to be running a network which sold Romanian Orthodox icons "for pledges".[84] Both leaders were arrested,[85] with their Gazeta being singled out as a "rebels' nest".[62] The movement went inactive for more than a decade.[86] Although Valescu still convened a Congress of the Peasants in 1910, its demands were moderate, and its focus was on petitioning; other, more radical cells claiming the "peasants' party" pedigree were founded by Nicolae Basilescu and Alexandru Popescu-Berca. Overall, Valescu supported the reforms enacted by the National Liberal Party.[87] As Drăghicescu notes, the latter now integrated a Poporanist current, and made the peasant issue, including advocacy for land reform, one of its core doctrines.[88]

Ultimately, following World War I, land reform and universal suffrage were introduced throughout the newly established Greater Romania, making it possible for teacher Ion Mihalache to form his own Peasants' Party, the first of several interwar agrarianist movements. He was joined by Valescu, who took a Senate seat at Argeș in the elections of 1919.[59][89] According to political essayist Pamfil Șeicaru, the party's solid win Argeș, Muscel, and Dâmbovița was owed primarily to Dobrescu-Argeș's fieldwork in previous decades.[90] The movement he helped create remained factionalized to a degree: in 1920, at Priboieni, the folklorist Constantin Rădulescu-Codin relaunched Gazeta Țăranilor as a National Liberal mouthpiece, critical of Mihalache's policies.[91] The period also saw a reevaluation of Dobrescu's role in the movement. Research into his politics was hampered by the destruction of his Țĕranul, issues of which are exceedingly rare.[92]

By the 1930s, the consolidated National Peasants' Party (PNȚ) was claiming Dobrescu as its patriarch. An earlier bust done by Frederic Storck from live sittings[93] was raised at Curtea de Argeș in October 1933. PNȚ leaders Mihalache and Armand Călinescu were guest speakers at that ceremony.[94] Also for the occasion, Adevărul revisited its earlier stances, dedicating Dobrescu a retrospective and quoting him on its frontispiece. As argued therein by editor Tudor Teodorescu-Braniște, "most of [Dobrescu's] goals, to this day, are just goals". The land reform, he claimed, was haphazard and purposefully unsustainable; the enfranchisement was also compromised by "savage elections", and by Mihalache's own praise of corporatism.[29] In January 1937, a "Dobrescu-Argeș Canteen" was founded by the PNȚ for rural peasants studying in Bucharest. Speaking at its inauguration rally, which doubled as an anti-fascist protest, Paul Bujor honored Dobrescu as the "precursor and martyr of peasantism".[95] Pitești also hosted a Dobrescu-Argeș cooperative bank, managed by the PNȚ cadre Petre Gr. Dumitrescu.[96]

During the communist period, Dobrescu-Argeș was subjected to official criticism. In one novel of the period, Isac Ludo revisited the embezzling scandal, suggesting that other politicians were secretly admiring the leader of the "so-called peasants' party" for his criminal resourcefulness.[97] A cultural club and research society bearing his name was founded at Mușătești in 1973, but was largely inactive.[98] In 1974, the Romanian Communist Party Institute of Studies officially designated Dobrescu a representative of the "numerically weak village bourgeoisie", noting that his solutions "could not lead to solving the basic social problems of the oppressed masses, urban as well as rural."[99] His activity was again reviewed positively after the Romanian Revolution of 1989. A high school in Curtea de Argeș was named after him in 1990, as was a street in Pitești.[37]

Notes

- Dinu C. Giurescu, Dicționar biografic de istorie a României, pp. 176–177. Bucharest: Editura Meronia, 2008. ISBN 978-973-7839-39-8

- Dobridor, p. 213

- Octavian Ungureanu, "Tudor Vladimirescu în conștiința argeșenilor. Momente și semnificații", in Argessis. Studii și Comunicări, Seria Istorie, Vol. VIII, 1999, p. 171

- Dobridor, p. 213. See also Teodorescu, p. 110

- Dobridor, pp. 14–15

- Dobridor, pp. 213–214

- Dobridor, p. 214

- Neagoe, p. 510

- Neagoe, p. 511

- Dobridor, p. 209

- Dobridor, pp. 196, 211

- Dobridor, p. 212; Neagoe, p. 511

- (in Romanian) Alin Ion, "Povestea incredibilă a unui ales al poporului cum nu vom mai găsi în România: Dincă Schileru, deputatul care venea în Parlament în straie populare", in Adevărul, Târgu Jiu edition, June 9, 2015

- Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", p. 517. See also Dobridor, p. 214

- Dobridor, pp. 14–15, 211–212; Neagoe, p. 511

- Dobridor, pp. 211–212

- Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", pp. 513–517

- Iosa, pp. 1419–1420. See also Niculae, pp. 70–71

- Iosa, p. 1426

- Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", p. 517

- Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", p. 516

- "Ultime informațiuni", in Epoca, October 15 (27), 1888, p. 3

- "A 3a edițiune. Resultatul alegeri Col. III", in Epoca, November 30 (December 12), 1888, p. 3

- "Dupe interpelări" and "Discursul Domnului Theodor Rosetti asupra rescoalei țeranilor", in Epoca, November 30 (December 12), 1888, pp. 1, 2

- "Fizionomia Camereĭ", in Lupta, February 22, 1889, p. 1

- Eidelberg, p. 189

- "Votul fortificațiunilor", in România Liberă, April 6 (18), 1889, p. 1

- "A 2a edițiune. Camera. Ședința de la 2 Decembre 1888", in Epoca, December 3 (15), 1888, p. 3

- Tudor Teodorescu-Braniște, "Inscripții pe soclu", in Adevărul, October 28, 1933, p. 1

- Eidelberg, pp. 29, 106, 160–162, 233–234

- Panu, p. 35

- "Indigenatele", in Revista Israelită, Nr. 4/1889, pp. 88–89

- Nicolescu, p. 46

- "Informațiuni", in Epoca, February 4 (16), 1889, p. 2

- "Camera. Ședința de la 17 Februarie 1889" and "Ultime informațiuni", in Epoca, February 18 (March 2), 1889, pp. 2–3

- "Ultime informațiuni", in Epoca, February 15 (27), 1889, p. 3

- (in Romanian) Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului – D, at the University of Pitești Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului site, p. 34

- Neagoe, pp. 510, 511; Nicolescu, pp. 43–44, 47, 68; Teodorescu, p. 111

- Iorga & Bacalbașa, pp. 165, 186–187

- Nicolescu, p. 68

- "Cărți noi. Tipografiile din România dela 1801 până azi de Gr. Crețu, profesor", in Noua Revistă Română, Nr. 12/1911, p. 261

- Alexandru Macedonski, "Notițele Literatoruluĭ. Banchiet Țĕrănesc", in Literatorul, Nr. 6/1892, p. 16

- Neagoe, pp. 510–511

- "Deputatul Dobrescu-Chitanță judecat de Timpul și Adevĕrul", in Voința Națională, September 12 (24), 1890, p. 2

- Iosa, p. 1425; Panu, p. 35

- Satyr, "Satira zileĭ. Chitanțele lui CC. Lascarache", in Adevărul, May 2, 1893, p. 1

- Nicolae Isar, "Învățămîntul în dezbaterile Parlamentului în anii 1892—1893", in Revista Istorică, Vol. I, Issue 3, March 1990, p. 267

- "Fizionomia Camereĭ. Ploconul de 300,000 leĭ", in Lupta, November 26, 1892, pp. 1–2

- Bran, "Hoția de la Cameră" and Rigolo, "Satira zilei. Tamazlîcul parlamentar", in Adevărul, November 25, 1933, p. 1

- Alexandru Vlahuță, Un an de luptă, pp. 27–30. Bucharest: Editura Librărieĭ Carol Müller, 1895

- Panu, pp. 34–35

- "Cronica săptămâneĭ", in Foaia Populară, Nr.8/1900, pp. 2–3

- Iorga & Bacalbașa, p. 186

- Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea, Lumină tuturora... (Discursul Domnuluĭ B. Ștef. Delavrancea pronunțat în ședința Camereĭ de la 17 Martie 1895), pp. 3–8, 18–21, 35–37. Bucharest: Tipografia Voința Națională, 1895

- Dobridor, pp. 212–213

- Brett, p. 31; Neagoe, pp. 511–512

- Nicolae, p. 72

- "Rezultatele C. III Cameră", in Epoca, November 3, 1895, pp. 1–2

- (in Romanian) Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului – V, at the University of Pitești Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului site, pp. 266–267

- Iosa, pp. 1425–1426, 1429

- Simionescu, p. 93

- Teodorescu, p. 111

- "Informații", in Epoca, May 30, 1889, p. 2

- Ornea, pp. 24–25

- Iosa, pp. 1425–1429. See also Eidelberg, p. 185; Niculae, p. 73

- Ornea, p. 23

- "Corpurile Legiuitoare. Camera Deputaților. Ședința de la 10 Martie (urmare). Interpelarea d-luĭ Dobrescu-Argeș", in Epoca, March 12, 1898, p. 3

- Aurelian Chistol, "Aspecte legate de activitatea lui Ion I. C. Brătianu în fruntea Ministerului Lucrărilor Publice (31 martie 1897 – 30 martie 1899)", in Argesis. Studii și Comunicări, Seria Istorie, Vol. XVII, 2008, p. 208

- "Afacerea Dobrescu-Argeș", in Epoca, June 5, 1898, p. 3

- Brett, pp. 31–32; Dobridor, pp. 214–216; Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", p. 517; Neagoe, p. 512; Simionescu, p. 93

- Nicolae P. Leonăchescu, "Lichidarea 'Treimii proprietății' din Stroești-Argeș", in Argessis. Studii și Comunicări, Seria Istorie, Vol. VIII, 1999, p. 230

- Ludo, p. 308

- Ludo, pp. 308–309; Ionescu, "Momente din lupta...", pp. 516–517

- Teodorescu, p. 110

- N. Leobeanu, "Dosarul lui Bogdan-Văcărești. 'Directorul ziarului Seara' autorul moral al unor măceluri țărănești", in Opinia, June 20, 1913, p. 2

- "Ultima oră", in Epoca, June 24, 1898, p. 3

- Dobridor, pp. 214–216

- Drăghicescu, p. 88

- Eidelberg, pp. 138–147, 184–189; Ionescu, "Bucureștii...", pp. 133–134, and "Momente din lupta...", p. 517; Neagoe, p. 512; Scurtu, p. 512

- Eidelberg, p. 155; Ionescu, "Bucureștii...", p. 133; Iorga & Bacalbașa, p. 165; Scurtu, pp. 512–516

- Eidelberg, pp. 135–136, 138–139, 146–147, 155, 184–187, 205–207, 210

- Eidelberg, pp. 187–189, 205–228

- Ionescu, "Bucureștii...", pp. 133–134

- Ionescu, "Bucureștii...", p. 134

- Scurtu, p. 512

- Brett, pp. 31–32; Neagoe, p. 512

- Scurtu, pp. 512–518

- Drăghicescu, pp. 88–89

- "Anexă", in Bogdan Murgescu, Andrei Florin Sora (eds.), România Mare votează. Alegerile parlamentare din 1919 "la firul ierbii", p. 414. Iași: Polirom, 2019. ISBN 978-973-46-7993-5

- Bogdan Teodorescu, "Teleorman", in Bogdan Murgescu, Andrei Florin Sora (eds.), România Mare votează. Alegerile parlamentare din 1919 "la firul ierbii", p. 364. Iași: Polirom, 2019. ISBN 978-973-46-7993-5

- Simionescu, p. 94

- Nicolescu, p. 43

- Alexandru Saint-Georges, "Texte și documente. Activitatea de medalist a sculptorului Frederic Storck", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Nr. 9/1943, pp. 627–628

- "Actualitățile săptămânii", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Nr. 353, November 1933, p. 5

- Dr. P., "Studențimea, sub flamura lui Dobrescu-Argeș...", in Adevărul, January 31, 1937, p. 1

- (in Romanian) Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului – D, at the University of Pitești Enciclopedia Argeșului și Muscelului, p. 60

- Ludo, pp. 308–309

- Nicolae P. Leonăchescu, "Monografia Vâlsăneşti – un sat pe Valea Vâlsanului, de Vasile P. Moise, între Capitoliu și Tarpeia", in Studii și Comunicări, Vol. VIII, 2015, pp. 548, 553

- Institutul de Studii Istorice și Social-Politice de pe lîngă C.C. al P.C.R., Întrebări și răspunsuri pe teme din istoria Partidului Comunist Român și a mișcării muncitorești din România, pp. 75–76. Bucharest: Editura Politică, 1974. OCLC 601455562

References

- Daniel Brett, "Normal Politics in a Normal Country? Comparing Agrarian Party Organization in Romania, Sweden and Poland before 1947", in New Europe College Yearbook, 2011–2012, pp. 21–52.

- Ilariu Dobridor, Oameni ridicați din țărănime. Bucharest: Fundația Culturală Regală Regele Mihai I, 1944. OCLC 895104973

- Dumitru Drăghicescu, Partide politice și clase sociale. Bucharest: Tipografia Reforma Socială, 1922.

- Philip Gabriel Eidelberg, The Great Rumanian Peasant Revolt of 1907. Origins of a Modern Jacquerie. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1974. ISBN 90-04-03781-0

- Matei Ionescu,

- "Bucureștii în timpul răscoalelor țărănești din 1907", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. 5, 1967, pp. 133–144.

- "Momente din lupta iredentei române transilvane în anii 1884—1887", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Nr. 3/1967, pp. 511–522.

- Nicolae Iorga, Constantin Bacalbașa, Istoria presei românești. Bucharest: Editura Adevĕrul, 1922.

- Mircea Iosa, "Încercări de modificare a legii electorale în ultimul deceniu al secolului al XIX-lea", in Revista de Istorie, Nr. 8/1977, pp. 1419–1431.

- Isac Ludo, Domnul general guvernează. Bucharest: Editura de stat pentru literatură și artă, 1953.

- Stelian Neagoe, "Cartea românească și străină de istorie. Organizarea politică a țărănimii (sfîrșitul secolului XIX-lea — începutul secolului al XX-lea), Editura științifică și enciclopedică", in Revista de Istorie, Nr. 5/1986, pp. 509–512.

- G. C. Nicolescu, Ideologia literară poporanistă. Contribuțiunea lui G. Ibrăileanu. Bucharest: Institutul de Istorie Literară și Folclor, 1937.

- Vasile Niculae, "1893–1973: 80 ani de la crearea P.S.D.M.R. Liga votului universal", in Magazin Istoric, August 1973, pp. 70–73.

- Z. Ornea, Sămănătorismul. Bucharest: Editura Fundaţiei Culturale Române, 1998. ISBN 973-577-159-4

- George Panu, Portrete și tipuri parlamentare. Bucharest: Tipografia Lupta, 1892. OCLC 798081254

- Ioan Scurtu, "Contribuții privind mișcarea țărănistă din România în perioada 1907—1914", in Studii. Revistă de Istorie, Nr. 3/1968, pp. 499–521.

- Dan Simionescu, "Din istoria folclorului și folcloristicii. Folcloristul C. Rădulescu-Codin (1875—1926)", in Revista de Folclor, Nr. 4/1957, pp. 91–121.

- Nicolae Gh. Teodorescu, "Muzeul din Mușătești, județul Argeș, mărturie a contribuției satului la istoria patriei", in Muzeul Național (Sesiunea Științifică de Comunicări, 17–18 Decembrie 1973), Vol. II, 1975, pp. 109–113.