Constantin Shapiro

Constantin Aleksandrovich Shapiro (Russian: Константин Александрович Шапиро, Hebrew: קוֹנְסְטַנְטִין אָלֶכְּסַנְדְרוֹבִיץ' שַׁפִּירָא; 1841 – 23 March 1900), born Asher ben Eliyahu Shapiro (Hebrew: אָשֵׁר בֶּן אֵלִיָּהוּ שַׁפִּירָא) and known by the pen name Abba Shapiro (Hebrew: אַבָּ״א שַׁפִּירָא), was a Hebrew lyric poet and photographer. Though he converted to Russian Orthodoxy at an early age, Shapiro nonetheless retained lifelong ties to Judaism, Zionism, and his mitnagedic roots, themes of which featured prominently in his poetry.[1] He was described by Yeshurun Keshet as "a poet of the national legend, the first author of the ballad in Hebrew literature."[2]

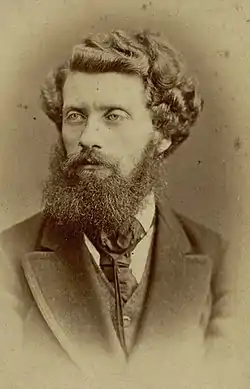

Constantin Shapiro | |

|---|---|

Shapiro in 1870 | |

| Born | Asher ben Eliyahu Shapiro 1839 |

| Died | 23 March 1900 (aged 60–61) St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Burial place | Strelna, Russia |

| Occupation | Poet and photographer |

| Writing career | |

| Language | Hebrew |

| Genre | Lyric poetry |

| Notable works | Me-Ḥezyonot Bat 'Ammi (1884–1898) Mi-Shire Yeshurun (1911) |

| Years active | 1879–1900 |

Biography

Early life

Constantin Shapiro was born to a religious Jewish family in Grodno, where he received a traditional yeshiva education. He began writing secular poetry in his youth, much to the consternation of his father, who used all means to prevent him from following the path of the Haskalah.[3] His parents married him off at the age of 15, but the marriage was shortly annulled.[4] He eventually left his hometown for Białystok and Vienna, and from there to St. Petersburg in 1868 to enter the Academy of Art, which he left after a short time to learn photography.

Shapiro fell gravely ill with typhus, at which time he found out that his Russian girlfriend was pregnant. Fearing his imminent passing, he married her and was baptised so that she and her baby would not be tainted.[5] Shapiro's deep sense of guilt for converting to Christianity would later feature prominently in his writing.[6]

Photography

Shapiro became the personal photographer of many prominent Russian officials, including members of the royal family.[7] He was a close friend of Fyodor Dostoevsky, and also photographed Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Ivan Turgenev, Ivan Goncharov, and other leading Russian writers.[8][9] Shapiro recorded performances by Vasilii Andreev-Burlak for a photo series devoted to Nikolai Gogol's short story Diary of a Madman, published as an album in 1883.[10] An early attempt to capture a performance sequence, each photograph corresponded to a moment in the context of the monologue.[11]

Shapiro's exhibitions at the All-Russia Exhibitions of 1870 and 1882 were met with great approbation, and in 1880 his work appeared in the St. Petersburg Portrait Gallery of Russian Writers, Scientists and Actors.[12] He was awarded a Silver Medal by Emperor Alexander II in 1883.[13]

Literary career

In the 1870s, Shapiro began holding a regular literary salon at his home and writing poetry for the Hebrew papers and magazines. His first published poem, "Me-Ḥezyonot Bat 'Ammi" ('From the Visions of the Daughter of My People', 1884–1898), at once gained for him a place in the foremost rank of Hebrew poets. His poem "David Melekh Yisrael Ḥay ve-Kayam" ('David, King of Israel Still Lives,' 1884) is considered the first Hebrew poem to present popular traditions in a folk ballad form.[14] This type of poem was subsequently taken up by David Frischmann, Jacob Kahan, and David Shimoni.[15]

Following the 1881–82 pogroms across the Russian Empire, Shapiro became an avowed Zionist and dreamed of going to Eretz Israel. Shapiro's anthology Mi-Shire Yeshurun ('From the Songs of Jeshurun', collected in 1911) contains his most famous poem, "Beshadmot Beit-Leḥem" ('In the Fields of Bethlehem'), in which Rachel grieves for her sons as she walks up from her grave toward a silent Jordan River.[5] It contains a section in which Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and his sons, led by Rachel, all rise from their graves and urge God to end the exile. The poem, set to music by Hanina Karchevsky, became a popular anthem of labour Zionism and the basis for a well-known Israeli folk dance.[16]

Other poems of Shapiro include "Amarti Yesh Li Tikvah," a translation of Friedrich Schiller's "Resignation", and "Sodom", an allegorical description of the Dreyfus affair. He also published "Turgenev ve-Sippuro Ha-Yehudi", a critical essay on Ivan Turgenev's story The Jew, in Ha-Melitz (1883).[7]

Death and legacy

Shapiro died in 1900 in St. Petersburg, leaving several tens of thousands of rubles to the Odessa Committee, which supported Jewish settlements in Palestine of the First Aliyah.[5] His poetry was collected in one volume and published posthumously in 1911 by Ya'akov Fichmann under the title Shirim Nivḥarim.[17]

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constantin Shapiro. |

References

![]() Rosenthal, Herman; Hurwitz, S. (1901–1906). "Shapiro, Constantin". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 233.

Rosenthal, Herman; Hurwitz, S. (1901–1906). "Shapiro, Constantin". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 11. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 233.

- Assaf, David (2010). Untold Tales of the Hasidim: Crisis and Discontent in the History of Hasidism. Waltham, Massachusetts: Brandeis University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-61168-194-9. OCLC 794670877.

- Keshet, Yeshurun (1975). "Al Constantin A. Shapiro". Molad (in Hebrew). 30 (33–34): 504.

- Waxman, Meyer (1947). A History of Jewish Literature: From the Close of the Bible to Our Own Days. Bloch Publishing Company. p. 210.

- Holtzman, Avner (2008). "Shapiro, Konstantin Abba". In Hundert, Gershon (ed.). YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Translated by Fachler, David. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Kolodny, Ruth Bachi (14 December 2012). "Hebrew Poet Turned Christian Convert, But Always a Lover of the Jewish People". Haaretz. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- "Шапиро Константин Абба". Shorter Jewish Encyclopedia (in Russian). 10. 2001. pp. 59–61. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Kressel, Getzel. "Shapiro, Abba Constantin". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference.

- "Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky, by Konstantin Shapiro, 1880". Columbia College, Columbia University in the City of New York. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Gordin Levitan, Eilat. "Konstantin Shapiro". Grodno Stories. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Senelick, Laurence (2007). Historical Dictionary of Russian Theater. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8108-6452-8. OCLC 263935402.

- John Hannavy (2013). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. London: Routledge. p. 1229. ISBN 978-1-135-87326-4. OCLC 868381077.

- "Konstantin Shapiro (1840–1900)". La Gazette Drouot. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "Фотограф Константин Александрович Шапиро". Photographer.ru. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Yaniv, Shlomo (September 1989). "Wieseltier and the Evolution of the Modern Hebrew Ballad". Prooftexts. Indiana University Press. 9 (3): 230. JSTOR 20689249.

- Yaniv, Shlomo (1990). "The Baal Shem-Tov Ballads of Shimshon Meltzer". Hebrew Annual Review. 12: 167–183. hdl:1811/58768. ISSN 0193-7162.

- Raz, Yosefa (2015). ""And Sons Shall Return to Their Borders": The Neo-Zionist (Re)turns of Rachel's Sons". The Bible and Critical Theory. 11 (2): 18–35. ISSN 1832-3391.

- Shapiro, Abba Constantin (1911). Fichman, Ya'akov (ed.). Shirim Nivḥarim [Selected Poems] (in Hebrew). Warsaw: Tushiyah. OCLC 643592956.