Coromandel lacquer

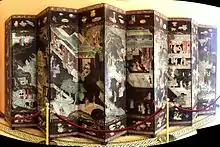

Coromandel lacquer is a type of Chinese lacquerware, latterly mainly made for export, so called only in the West because it was shipped to European markets via the Coromandel coast of south-east India, where the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) and its rivals from a number of European powers had bases in the 18th century.[1] The most common type of object made in the style, both for Chinese domestic use and exports was the Coromandel screen, a large folding screen with as many as twelve leaves, coated in black lacquer with large pictures using the kuan cai (literally "incised colors") technique, sometimes combined with mother of pearl inlays. Other pieces made include chests and panels.[2]

_(7365169420).jpg.webp)

But in Europe cabinet-makers often cut the screens into a number of panels, which were inserted into pieces of furniture made locally in the usual European shapes of the day, or mounted within wood panelling on walls.[3] This was often also done with Japanese lacquer in rather different techniques, but "Coromandel" should only be used to refer to Chinese lacquer. The peak of the fashion for panelling rooms was the late 17th century.[4] By the 18th century, Chinese wallpaper began to reach Europe, and generally replaced lacquer panels as a cover for walls.[5]

At the time of the first imports in the 17th century, Coromandel lacquer was known in English as "Bantam ware" or "Bantam work" after the VOC port of Bantam on Java, modern Bantem, Indonesia.[6] The first recorded use of "Coromandel lacquer" is in French, from a Parisian auction catalogue of 1782.[7]

Technique and iconography

A combination of lacquer techniques are often used in Coromandel screens, but the basic one is kuan cai or "incised colors",[8] which goes back to the Song dynasty. In this the wood base is coated with a number of thick layers of black or other dark lacquer, which are given a high polish. In theory the shapes of the pictorial elements are then cut out of the lacquer, though in screens where a high proportion of the area is taken up by the pictorial elements, some method of reserving the main elements and saving expensive lacquer was probably used. The areas for the picture elements might be treated in a variety of ways. The final surface might be painted in coloured lacquer, oil paints, or some combination, perhaps after building up the surface with putty, gesso, plaster, lacquer, or similar materials as filler, giving a shallow relief to figures and the like.[9]

A different technique was to use inlays of mother of pearl, which had been used on lacquer since at least the Song dynasty and revived in popularity in the 16th century, perhaps also using tortoiseshell, ivory, and metal, especially gold for touches. The mother of pearl was often engraved and stained with colours. The mother of pearl technique was, at least initially, more expensive and produced for the court (who also used screens painted by court artists), and the filled technique apparently developed for a wealthy clientele outside the court. The screens seem to have been mostly made in Fujian province in south China, traditionally a key area for lacquer manufacturing.[10]

Up to thirty layers of lacquer could be used. Each layer could have pictures and patterns incised, painted, and inlaid, and this created a design standing out against a dark background. The screens were made in China and appeared in Europe during the 17th century,[11] remaining popular into the 18th.

The main designs are typically of two major groups: firstly courtly "figures in pavilions", often showing "spring in the Han palace", and secondly landscape designs, often with emphasis on birds and animals.[12] Some screens illustrate specific episodes from literature or history. Typically borders run above and below the main scene. These often show the "hundred antiques" design of isolated "scholar's objects", antique Chinese objets d'art, sprays of flowers, or a combination of the two.[13] There are often smaller borders between the main image and these, and at the edges. Sometimes both sides of the screen are fully decorated, usually on contrasting subjects. The earlier examples made for the Chinese market often have inscriptions recording their presentation as gifts on occasions such as birthdays;[14] they came to represent a standard present on the retirement of senior officials.[15] According to the V&A, "So far all known dated kuan cai screens are from the Kangxi period" (1654–1722).[16] Later pieces were mostly made for European markets and are of lower quality, many rather crude.[17]

Treatment in Europe

At the peak period in the decades around 1700 the main customers for screens shipped by the VOC were the English. The original fashion may have been Dutch; it was brought to England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, and to Germany by the princely marriages of the daughters of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange and his wife Amalia of Solms-Braunfels. Small rooms panelled in lacquer, "lacquer cabinets", were built in Berlin in 1685–95, Munich in 1693 with another in 1695, and Dresden in 1701.[18] This fashion seems to have died away rapidly after 1700, probably largely replaced in England with tapestries using similar Asiatic iconography for royalty and the top of the market (examples remain at Belton House), and then later wallpaper.[19]

None of the English or rooms panelled in lacquer have survived, but the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has a room from the Stadtholder's palace at Leeuwarden, which has recently been restored and placed on display (Phillips Wing).[20] In the Netherlands the English speciality of gilded leather with impressed oriental designs was imported for grand houses around the 1720s. The Europeans were vague on the differences between Chinese, Japanese, Indian and other East Asian styles, and English tapesty-makers replicated the feel of Coromandel lacquer subjects with the individual figures adapted from Mughal miniatures they had to hand.[21]

Interest then turned to incorporating lacquer panels, whether imported as such or cut down from screens, into pieces of furniture, on a carcass of European wood in "Japanning" imitation lacquer, lavishly ornamented with ormolu mounts.[22] Bernard II van Risamburgh, who initialled his pieces "B.V.B.R." was a leading Parisian ébéniste in the mid-18th century, among those who often incorporated both Chinese and Japanese lacquer into his pieces, the latter usually in the black and gold maki-e style.[23] Such pieces were sawn through, if decorated on both sides, and sometimes needed to be slowly bent into a curved shape for bombe commodes and other pieces. Madame de Pompadour was especially keen on Asian lacquer panels in furniture, and was probably largely responsible for the very high prices recorded for such pieces, sometimes 10 times or more the price of ordinary furniture of equivalent quality.[24]

After the fashion for Coromandel lacquer died away in the 18th century, demand for screens remained fairly low until a revival in the 1880s, when it revived as part of a general taste for Oriental art, led by blue and white porcelain.[25] The Victoria and Albert Museum paid £1,000 for a screen in 1900,[26] whereas one in the famous Hamilton Palace Sale of 1882 had only fetched £189.[27] In Vita Sackville-West's novel The Edwardians, published in 1930 but set in 1905–10, a "coromandel screen" is mentioned as being in a room that is "impersonal, conventional, correct", typifying the style of those who "unquestioningly followed the expensive fashion".[28] By the 20th century screens were again being manufactured in China, and imported via Hong Kong for dealers.[29]

In the 20th century, the famous fashion designer Coco Chanel (1883–1971) was an avid collector of Chinese folding screens, especially the Coromandel screens, and is believed to have owned 32 folding screens of which eight were housed in her apartment at 31 rue Cambon, Paris.[30] She once said:

- I've loved Chinese screens since I was eighteen years old. I nearly fainted with joy when, entering a Chinese shop, I saw a Coromandel for the first time. Screens were the first thing I bought.[31]

Having rather dwindled, prices for Coromandel screens revived somewhat with the influx of Chinese money into the art market, and a screen fetched well over estimate at $US 602,500 in 2009, then the record price, selling to a dealer from Asia.[32]

Screen in Munich; coastal landscape scene, with "hundred antiques" border

Screen in Munich; coastal landscape scene, with "hundred antiques" border_(7179942367).jpg.webp) Detail of the medal cabinet shown above

Detail of the medal cabinet shown above Detail of a screen shown above, 1750-1800

Detail of a screen shown above, 1750-1800 A Chinese Coromandel screen is seen in the oil painting Chopin (1873) by Albert von Keller. A coastal landscape can be seen in the centre, with floral wreaths on the turned back side panels.

A Chinese Coromandel screen is seen in the oil painting Chopin (1873) by Albert von Keller. A coastal landscape can be seen in the centre, with floral wreaths on the turned back side panels.

Notes

- N. S. Brommelle, Perry Smith (eds), Urushi: Proceedings of the Urushi Study Group, June 10–27, 1985, Tokyo, p. 254, 1988, Getty Publications, ISBN 0892360968, 9780892360963, fully online

- Rawson, 360

- Alayrack-Fielding, 83; Osborne, 205

- Van Campen, 137

- Alayrack-Fielding, 83

- Alayrack-Fielding, 82–83; Osborne, 205; V&A 130–1885

- V&A 130–1885

- Clunas, 61

- Pedersen; Osborne, 205; Alayrack-Fielding, 83: Watt and Ford, 3–6, 23–26, 34, 36

- Pedersen; Osborne, 205; Alayrack-Fielding, 83: Watt and Ford, 3–6, 23–26, 34, 36; Pelham

- Coromandel screen. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 23 September 2011

- V&A 130–1885

- V&A 130–1885

- Kerr, 118

- Clunas, 61

- V&A 130–1885

- Rawson, 360

- van Campen, 140

- van Campen, 136–137, 140–145

- Rijksmuseum page; van Campen 136–137, Jan Dorscheid, Paul Van Duin, Henk Van Keule, in: Gabriela Krist, Elfriede Iby (eds), Investigation and Conservation of East Asian Cabinets in Imperial Residences (1700–1900): Lacquerware & Porcelain, (Conference 2013 Postprints), pp. 239–259, 2015, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna,

- van Campen, 136–137, 140–145

- van Campen, 142–145

- European Furniture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Highlights of the Collection, 2006, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0300104847, 9780300104844, google books; Metropolitan Museum of Art, Europe in the Age of Monarchy, p. 154, 1987, ISBN 0870994492, 9780870994494, google books; Alayrack-Fielding, 82–83

- Reitlinger, 25–27

- Reitlinger, Chapter 7 on the general revival, 219–220 on lacquer

- van Campen, 145; a different screen to "V&A 130–1885".

- van Campen, 145

- van Campen, 145 (quoted), 146

- van Campen, 149

- "COCO CHANEL'S APARTMENT THE COROMANDEL SCREENS". Chanel News. June 29, 2010.

- Delay, Claude (1983). Chanel Solitaire. Gallimard. p. 12. Cited in: "COCO CHANEL'S APARTMENT THE COROMANDEL SCREENS". Chanel News. June 29, 2010.

- Moonan, Wendy, "Asian antique sales rocket in New York", Japan Times, 2 October, 2009

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coromandel lacquer. |

- Alayrack-Fielding, Vanessa in: Feeser, Andrea, Goggin, Maureen Daly, Fowkes Tobin, Beth (eds), The Materiality of Color: The Production, Circulation, and Application of Dyes and Pigments, 1400–1800, 2012, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 1409429156, 9781409429159, google books

- Clunas, Craig (1997). Pictures and visuality in early modern China. London: Reaktion Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-86189-008-5.

- Kerr, Rose, ed., Chinese Art and Design: the T.T. Tsui Gallery of Chinese Art, 1991, Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 1851770178

- Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- Pedersen, Bent L., "China, X, Lacquer. 7. Qing and after (from 1644).", Oxford Art Online, Subscription required

- "Pelham": Pelham Galleries, "A Magnificent Chinese Twelve-Fold Coromandel Lacquer Screen, Kangxi, Circa 1680"

- Rawson, Jessica (ed). The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, 2007 (2nd edn), British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714124469

- Reitlinger, Gerald; The Economics of Taste, Vol II: The Rise and Fall of Objets d'art Prices since 1750, 1963, Barrie and Rockliffe, London

- Van Campen, Jan, "'Reduced to a heap of monstruous shivers and splinters': Some Notes on Coromandel Lacquer in Europe in the 17th and 18th Centuries", The Rijksmuseum Bulletin, 2009, 57(2), pp. 136–149, JSTOR

- "V&A 130–1885", database details for a screen, Victoria and Albert Museum

- Watt, James C. Y., Ford, Barbara Brennan, East Asian Lacquer: The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection, 1991, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), ISBN 0870996223, 9780870996221, fully online

Further reading

- W. G. de Kesel and G. Dhont, Coromandel: Lacquer Screens, 2002, Ghent