Cost sharing reductions subsidy

The cost sharing reductions (CSR) subsidy is the smaller of two subsidies paid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) as part of the healthcare system in the United States. The subsidies were paid from 2013 to 2017 to insurance companies on behalf of eligible enrollees in the ACA to reduce co-payments and deductibles. They were discontinued by President Donald Trump in October 2017. The nature of the subsidy as discretionary spending (i.e., subject to annual appropriation by Congress) versus mandatory (i.e., paid automatically to eligible parties) was challenged in court by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives in 2014, although payments continued when the ruling in favor of the GOP was appealed by the Obama administration. The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that ending the payments would increase insurance premiums on the ACA exchanges by around 20 percentage points, resulting in increases in the premium tax credit subsidies, thereby adding nearly $200 billion to the budget deficits over the following decade.[1] Critics argued the decision was part of a wider strategy to "sabotage" the ACA.[2]

Description

The CSR subsidies were paid to insurance companies to reduce co-payments and deductibles for a group of roughly 7 million ACA enrollees in 2017, those earning 100%-250% of the federal poverty line (FPL), about $12,000 to $30,000 for an individual and $24,000 to $60,750 for a family of four. The second and larger type of subsidy, the premium tax credits, apply to all ACA enrollees earning 100-400% of the FPL.[3] When premiums rise, so do the premium tax credit subsidies, to limit after-subsidy premiums to a specified percentage of enrollee income. The premium tax credits were paid to approximately 8 million persons in 2017, out of the 10 million on the ACA exchanges. For those receiving the premium tax credit subsidies, there is little financial impact even from sizable increases in premiums, as the premium tax credit rises along with it. However, the two million persons on the exchanges that do not receive premium tax credit subsidies bear the full cost of premium increases. For scale, during 2017, approximately $7 billion in CSR subsidies will be paid, versus $34 billion for the premium tax credits.[4] It was payment of the CSR subsidies that was ended in 2017; the premium tax credit subsidies continue to be paid.

History of legal challenges

Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives sued the Obama administration in 2014, alleging that the CSR subsidy payments to insurers were unlawful because Congress had not appropriated funds to pay for them. The crux of the argument regarded the nature of the CSR subsidy as discretionary spending (i.e., subject to annual appropriation by Congress, like defense and other Cabinet department spending) versus mandatory (i.e., paid automatically to eligible parties, like Social Security, Medicare and the ACA premium tax credits). A May 2016 ruling by a federal judge in favor of the GOP would have stopped payment of the CSR subsidies, but the Obama administration appealed. The case, known as House v. Price, was pending at the time of Trump's decision to end the payments.[3]

Decision to end the subsidies

Trump announced on October 12, 2017[5] he would end the smaller of the two types of subsidies under the ACA, the cost sharing reduction (CSR) subsidies. President Trump argued that the CSR payments were a "bailout" for insurance companies and therefore should be stopped.[6]

CBO evaluation of ending the CSR subsidies

The CBO reported in August 2017 (prior to President Trump's decision) that ending the CSR payments might increase ACA premiums by 20 percentage points or more, with a resulting increase of nearly $200 billion in the budget deficit over a decade, as the premium tax credit subsidies would rise along with premium prices. The premium prices would rise because the ACA requires the insurers to reduce the co-payments and deductibles, even without the CSR subsidies, so the insurers would increase premiums to offset their losses. Since ACA after-subsidy premiums are capped as a percent of income, premium price increases result in premium tax credit subsidy increases.[1]

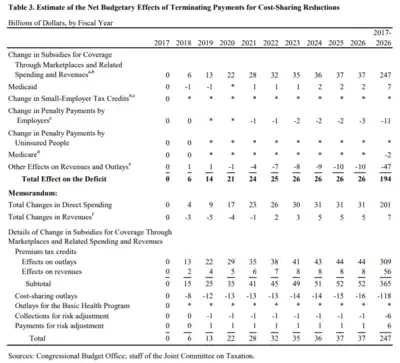

CBO described the major budgetary effects as follows for the 2017-2026 decade in total:

- There would be a $201 billion increase in outlays (spending) offset by a $7 billion net increase in revenues, for a net $194 billion increase in the budget deficit.

- Premium tax credits would increase by $365 billion, offset by ending CSR payments of $118 billion, a net effect of $247 billion.

- Medicaid spending would increase by $7 billion because of higher enrollment resulting from a reduction in the number of employers offering health insurance.

- Tax revenue would rise by $47 billion due to a shift to more taxable income, associated with a decrease in the number of persons enrolled in employment-based health insurance coverage.

- Higher employer mandate revenue of $11 billion, as more employers not offering coverage pay higher penalties.

CBO also estimated that initially up to one million fewer would have health insurance coverage, although more might have it in the long-run as the subsidies expand. In the short-term, a decline in coverage would be driven by fewer insurers participating in some markets. Over the long-term, an increase in coverage would derive from increases in premium tax credits. CBO expected the exchanges to remain stable (i.e., no "death spiral" before or after Trump's action) as the premiums would increase and prices would stabilize at the higher (non-CSR) level.[1]

CBO estimated that of the 10 million with private insurance via the ACA exchanges in 2017, about 8 million receive premium tax credit subsidies and will be shielded from premium increases, as their after-subsidy premiums are limited as a percentage of income under the ACA. However, those 2 million who do not receive subsidies face the brunt of the 20%+ premium increases, without subsidy assistance. This may adversely impact enrollment in 2018 and beyond. Another 13 million who are covered under the ACA's Medicaid expansion (in the 31 states that chose to expand coverage) should not be directly affected by Trump's action.[1][4]

Other impact assessments

Based on Trump's threats to end the CSR payments during early 2017, several insurers and actuarial groups estimated this resulted in a 20 percentage point or more increase in ACA exchange premiums for the 2018 plan year. In other words, premium increases expected to be 10% or less in 2018 became 28-40% instead.[7]

The Kaiser Family Foundation reported in April 2017 that ending the CSR payments could result in many insurers exiting the ACA marketplaces and those that remain could raise premiums around 19 percentage points. In 2018, the roughly $10 billion in savings from ending the CSR payments would be more than offset by $12 billion in increased spending on premium tax credits.[8]

Commentary

President Trump's argument that the CSR payments were a "bailout" for insurance companies and therefore should be stopped, actually results in the government paying more to insurance companies ($200B over a decade) due to increases in the premiums and related premium tax credit subsidies. Journalist Sarah Kliff therefore described Trump's argument as "completely incoherent."[6]

Murray—Alexander Individual Market Stabilization Bill

Senator Lamar Alexander and Senator Patty Murray reached a compromise to amend the Affordable Care Act to fund cost-sharing reductions.[9] The plan will also provide more flexibility for state waivers, allow a new "Copper Plan" or catastrophic coverage for all, allow interstate insurance compacts, and redirect consumer fees to states for outreach.

References

- "The Effects of Terminating Payments for Cost-Sharing Reductions | Congressional Budget Office". www.cbo.gov.

- "CBO says Trump's Obamacare sabotage would cost $194 billion, drive up premiums 20%". Vox. Retrieved 2017-10-17.

- Commonwealth Fund-Essential Facts about Health Reform Alternatives: Eliminating Cost-Sharing Reductions-Retrieved October 21, 2017

- "Federal Subsidies for Health Insurance Coverage for People Under Age 65: 2017 to 2027 | Congressional Budget Office". www.cbo.gov.

- Pear, Robert; Haberman, Maggie; Abelsonoct, Reed (October 12, 2017). "Trump to Scrap Critical Health Care Subsidies, Hitting Obamacare Again". The New York Times.

- Kliff, Sarah (October 18, 2017). "Sarah Kliff-Trump's stance on insurance 'bailouts' is completely incoherent" Vox.

- Scott, Dylan (October 18, 2017). "Obamacare premiums were stabilizing. Then Trump happened". Vox.

- "The Effects of Ending the Affordable Care Act's Cost-Sharing Reduction Payments". April 25, 2017.

- Thomas Kaplan and Robert Pear. "2 Senators Strike Deal on Health Subsidies That Trump Cut Off".CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)