Crémieux Decree

The Crémieux Decree (French: [kʁemjø]) was a law that granted French citizenship to the majority of the Jewish population in French Algeria (around 35,000), signed by the Government of National Defense on 24 October 1870 during the Franco-Prussian War. It was named after French-Jewish lawyer and Minister of Justice Adolphe Crémieux, who had founded the Alliance Israélite Universelle a decade earlier.[1]

The decree allowed for native Jews to automatically become French citizens while Muslim Arabs and Berbers were excluded and remained under the second-class indigenous status outlined in the Code de l'Indigénat. They could, on paper, apply as individuals for French citizenship, but it required that they formally renounce Islam and its laws,[2] and requests were very seldom accepted. That set the scene for deteriorating relations between the Muslim and Jewish communities. Tensions increased due to the distinction created between natives and citizens. Seeing one's indigenous brother become a first class citizen while being left as a second class citizen divided locals with animosity.[3] This proved fateful in the Algerian War of Independence, after which the vast majority of the French Jews of Algeria emigrated to France.

History

Jews first started migrating to Algeria during the Roman period.[4] The Spanish inquisition lead to an influx of Jewish migration.[5] In 1865 the Senatus-Consulte revised citizenship laws allowing the indigenous Algerian Jews and Muslims to apply for French Citizenship. The condition of such was forgoing traditional customs and laws to assimilate with French culture. Algerian culture prized itself on its customary practises and as a result application rates were low.[6] At this point in time France was focused on assimilating colonized people into French citizens with the goal of deporting a thriving French colony to Canada.[3] Seeing as European Jews already resided in France, the French held the belief that Algerian Jews were easier to convert to French people due to shared brethren.[3] Jews had gained recognition in France as a means of control. The French government realized through enabling Ashkenazi practises they could appoint chief Rabbis to be instilled with the duty to “inculcate unconditional obedience to the laws, loyalty to France, and the obligation to defend it”. By 1845 they had granted the same permission of system to Algeria in an effort of ‘civilization’ as Sephardic Jews were viewed as inferior by Europeans. They presumed by implementing such efforts as using French Jews as rabbis, Sephardic Jews would forgo their traditions.[7] The hope was this notion would create rapid assimilation from Algerian Jews to French.

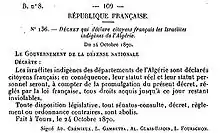

It was signed as Decree 136 of 1870[8] by Adolphe Crémieux as Minister of Justice, Léon Gambetta as Minister of the Interior, Alexandre Glais-Bizoin and Martin Fourichon as a naval and colonial minister. The ministers were members of the military government in Tours, the Gouvernement de la Défense nationale, since France was still at war, and the provisional government had its seat in Tours. The Muslim revolt of 1871 created distrust of the Indigenous non-Jews as it was openly established they would not respect French Authority.[3] This amplified French desire to attempt assimilation with Jews over other Indigenous communities as they felt it would be met with less resistance.

At the same time the naturalization regime in French Algeria was confirmed in Decree 137, determining that Muslims are not French citizens in the French colony of Algeria. The aim was to maintain the status quo, the sovereignty of France over its North African colonies. Five years later, in 1875, this was confirmed in the framework of the Code de l'indigénat.

Decrees 136 and 137 were published in Official Gazette of the City Tours (Bulletin officielle de la ville de Tours) on 7 November 1870.

From 1940 to 1943, the Crémieux Decree was abolished under the Vichy regime.

After effects of the decree

Within a generation most Algerian Jews came to speak French and embrace French culture in its entirety. Conflicts between Sephardic Jewish religious law and the writings of French law disfranchised community members as they attempted to navigate a legal system at odds with their established practise. The French army no longer was in total control of civilian life as Jews were viewed as equal.[3] Feelings of racial superiority took ahold of the French in Algeria creating a coping mechanism the French colonists refused to accept Jews are citizens creating a wave of anti-semitism that increasingly worsened well into the mid 1900s.[9] This led to a divide after the 1882 conquest of M'zab where the French government categorized Southern Algerian Jews and Northern Algerian Jews as distinct entities recognizing the rights of only the latter while treating the former as Indigenous.[10]

The decree was abolished in October 1940 accompanying the promotion of Anti-Jewish laws in France. After the Anglo-American landings in Algeria and Morocco in November 1942, the laws of Vichy were not abrogated by Admiral Darlan, kept in power by the Allies. After Darlan's assassination on December 24, 1942, General Giraud was appointed head of the French Civil and Military Commander-in-Chief and, in March 14, 1943, he revoked the anti-Semitic laws of Vichy and he reinstated the Crémieux decree. It remained in effect until Algerian Independence in 1962. Algeria officially won its independence in 1962 and the resentment felt towards Jews of Indigenous origin was amplified by years of recognized rights. In retaliation Algeria denied citizenship to all non Muslims upon being granted independence resulting in mass Jewish migration to France.[9]

Text of the decree

References

- Jean-Luc Allouche; Jean Laloum (1987). Les Juifs d'Algérie: images & textes. Editions du Scribe. ISBN 978-2-86765-008-6.

- Rouighi, Ramzi. "How the West made Arabs and Berbers into races – Ramzi Rouighi | Aeon Essays". Aeon. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Arendt, Hannah (6 July 2020). "Why the Crémieux Decree was Abrogated". Contemporary Jewish Record. 1: 116.

- Stern, Karen B. (2008). Inscribing devotion and death: archaeological evidence for Jewish populations of North Africa. Bril. p. 88.

- Suarez-Fernandez, Luis (6 July 2020). "The Edict of Explusion of the Jews: 1492 Spain". Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture. 177: 391–395 – via Edward Peters.

- Freidman, Elizabeth (1988). Colonialism & After. South Hadley, Massachusetts: Bergen.

- Stillman, Norman (2006). The Nineteenth Century and the impact on the West. The Jews of Arab Lands in Modern Times.

- (décret no 136 du 24 octobre 1870)

- "Religious Literacy Project: The Cremieux Decree". Harvard Divinity School. 6 July 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- Stein, Sarah Abrevaya (2014). Saharan Jews and the fate of Algeria. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.