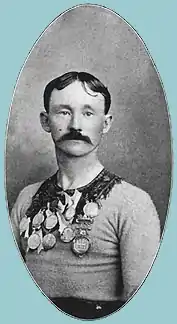

Daniel J. Maloney

Daniel John Maloney (circa 1879 – July 18, 1905) was an American pioneering aviator and test pilot who made the first high-altitude flights by man using a Montgomery glider in 1905.

Early life

A native of the Mission district in San Francisco, California, Daniel Maloney started his career in aviation by making parachute jumps and trapeze stunts from tethered hot-air balloons in the 1890s at Glen Park, San Francisco and Idora Park in Oakland. For these events he would often adopt the name “Professor Lascelles” or “Jerome Lesalles” although he was never formally trained as a professor. Many of the parachute jumps occurred at heights of 500–800 feet above the ground. By 1904 he became a full-time aerial exhibitionist.[1]

Aeronaut

Maloney was hired by John J. Montgomery in early 1905 to serve as an aeronaut for a tandem-wing glider design called the Montgomery Aeroplane. In February 1905, Maloney was trained by Montgomery on the workings of the glider at Aptos, California through a series of unmanned ballasted test flights, with the goal of launching the glider at high altitudes after ascending under a hot-air balloon. On March 16, 1905, this method was attempted for the first time with Maloney as pilot from Leonard’s Ranch at La Selva near Aptos. After a first failed launch attempt, on a second attempt Maloney was carried aloft in the glider under the balloon, released at an estimated 800 feet, and glided back under full control to a landing in a nearby apple orchard without damage. On March 17, 1905 a second flight, Maloney released at an estimated 3,000 feet above ground, and controlled the glider through a set of pre-defined turns at 45 degree bank angles back to the launch location with a successful landing. On March 20, 1905, Maloney was once again launched in the glider under the balloon, released at 3,000 feet above ground, and repeated the performance of March 17 with a flight of 18 minutes duration. These experiments of March 1905 were made in a private setting, with Montgomery increasing Maloney’s control authority over the aircraft on each subsequent flight.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] With each flight Maloney was able to control the glider through wing warping and a controllable elevator, and landed lightly on his feet.

On April 29, 1905, Maloney repeated these performances through a public exhibition at Santa Clara College as Montgomery’s aeronaut. By this time the glider had been re-christened as The Santa Clara in honor of the college. With a large crowd and members of the local press on hand, Maloney released at an estimated 4,000 feet above ground level, and glided in full control for roughly 20 minutes to a perfect landing a predetermined location.[9][10][11] This flight was the first public exhibition of a controlled heavier-than-air flying machine in the United States. Maloney and Montgomery made repeated demonstrations of the glider at various locations in the Bay area in the spring of 1905 with varying degrees of success owing to the complicated nature of hoisting the balloon aloft with a glider tethered beneath.[1]

Death

On July 18, 1905 Maloney and Montgomery repeated their demonstration at Santa Clara College. However, during the ascension a rope from the balloon struck the glider and damaged the rear cabane. Upon release from the balloon at altitude, and after making a few circles under complete control, Maloney dove the aircraft to increase speed and pulled up.[12] The glider suffered structural failure and plummeted to the Earth. Daniel Maloney died as a result of the injuries suffered during this crash. It remains unknown if Maloney was aware of the damage to the glider prior to release or did not think that the damage was severe enough to cause a structural failure.[1]

Recognition

A marker at Aptos, California marks the location of the March, 1905 glider trials.[13]

An obelisk dedicated by the citizens of Santa Clara, California on the campus of Santa Clara University marks the location of Maloney’s April, 1905 public flight.[14]

In San Jose, California, Daniel Maloney Drive is named in his honor and features John J. Montgomery Elementary School.[15]

See also

Research archives

- John J. Montgomery Collection, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, California.

- John J. Montgomery Personal Papers, San Diego Air and Space Museum, San Diego, California.

- John J. Montgomery Papers 1885-1947, The Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina Library, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

References

- Harwood, Craig; Fogel, Gary (2012). Quest for Flight: John J. Montgomery and the Dawn of Aviation in the West. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806142647.

- Masfrand, D.E. (1905). "Les Essais et la Catastrophe du 'Santa Clara'". L'Aérophile (August): 178–180.

- DeMeriel, P. (1905). "Un aeroplane a 1200 meters". La Nature (November 25): 412.

- Hermann Moedebeck, Fliegende Menschen! Das Ringen um die Beherrschung der Luft mittels Flugmaschinen (Berlin: O. Salle, 1905)

- "Notizen". Wiener Luftschiffer-Zeitung. 4 (8): 169–170. 1905.

- "The Montgomery Aeroplane". Automotor Journal. 10: 1079. 1905.

- A. Jeyasmet, “Máquina Veladora” El Heraldo de Madrid, March 31, 1905, MO XVI.—NUM. 5.242

- Coupin, Henri (1905). "Un descende de 1200 metres en aeroplane". Le Magasin Pittoresque (March): 139–140.

- "The Montgomery Aeroplane". Scientific American (May 20): 404. 1905.

- "Most Daring Test of Flying Machine Ever Made". Popular Mechanics. 7 (6): 703–707. 1905.

- "The Montgomery Aeroplane". Popular Mechanics. 7 (7): 703–707. 1905.

- The San Francisco Call, pg. 4, July 19, 1905

- "First High Altitude Aeroplane Flights March 1905 - Aptos, CA - E Clampus Vitus Historical Markers on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "John J Montgomery Obelisk - Santa Clara, CA - Obelisks on Waymarking.com". waymarking.com. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- "Evergreen School District: Search Results". eesd.org. Retrieved 28 April 2015.