David Wolffsohn

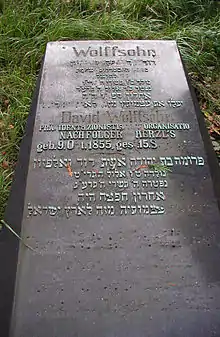

David Wolffsohn (Yiddish: דוד וואלפסאן; Hebrew: דוד וולפסון; 9 October 1855 in Darbėnai, Kovno Governorate – 15 September 1914) was a Lithuanian-Jewish businessman, prominent early Zionist and second president of the Zionist Organization (ZO).

David Wolffsohn | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 October 1855 |

| Died | 15 September 1914 (aged 58) |

Biography

David Wolffsohn was born in Darbėnai, Lithuania (then Russian Empire) to religious parents, Isaac and Feiga. He received an observant religious education from his parents and in 1872 was sent to Germany to avoid conscription into the Russian army. He moved to Memel, East Prussia, to leave his family, where he met Rabbi Isaac Rülf. Rülf accepted him as a student and taught Wolffsohn the German language, mathematics, and introduced him to the Hovevei Zion movement.

Then he moved to Lyck (today Ełk) were he met A. D. Gordon.[1]

Zionist activism

At the start of the 20th century, Wolffsohn accompanied Theodor Herzl in his travels to Palestine and Istanbul.

Wolffsohn was elected as the vice president of the Zionist Organization in the World Zionist Congress of 1905, and in 1907 became its president.

Before he died, he provided a short synopsis of his life for Nahum Sokolow, another Zionist leader of the time. In it he notes the following:[3]

- "My biography offers nothing of special interest to the general public. It may be divided into two parts : Zionist and personal. The Zionist portion is closely bound up with the history of our movement during the last ten years, and the facts concerning my modest work can hardly be distinguished from the general history of the movement. The personal portion of my career, on the other hand, contains nothing that transcends the ordinary. It is the simple story of a man of the Jewish people, of the Jewish Ghetto."

In addition to his early specifics noted above, he wrote:

- "My parents were poor, pious Jews. My late father, Isaac, was a talmudic scholar, and devoted his whole life to study and teaching. He earned a precarious livelihood from his lessons. My late mother, the type of a pious, good, clever Jewess, had to bear the burden of the household and the education of her children. Life in my parents' house was thoroughly Jewish. Zionism at that time was, of course, not known under that name, but, so far as the ideal of Zionism is concerned, I can say that in our home our lives were thoroughly inspired by the Zionist ideal. Till my fourteenth year I studied, according to the old Jewish custom, in the Cheder and Beth Hamedrash of my native town."

For later years, he wrote

- "In the early seventies I went to Memel, where my oldest brother was then residing. Here I made the acquaintance of Rabbi Dr. I. J. Rulf, who had great influence on my future career and way of thinking. Shortly afterwards I went to West Prussia, where I served several years as apprentice in a pious Jewish business-house. I also spent six months in Lyck, where I frequently met in his own house David Gordon, the editor of Ha'magid, who was one of the earliest Zionist pioneers. In 1877 I returned to Memel, where I set up in business for myself, and married. After some time I removed to East Friesland, and in 1887 to my present home in Cologne."

Of his Zionist activities, he said:

- "I can hardly give any data concerning my Zionist work. Zionism for me is hardly a thing that can be put into chronological, historical order. Zionism has been, rather, my life. Ever since I learned to think and feel I was a Zionist. I took a lively interest in the Choveve Zion movement and was in active correspondence with all the leaders of this movement in Germany. In 1894 I delivered in Cologne my first address on Zionism and helped to found the local society for the promotion and support of Jewish agriculture in Syria and Palestine, which was established in the same year. The appearance of Herzl's Judenstaat (in 1896) was epoch-making for me. This pamphlet made such a deep impression on me that I at once went to Vienna to introduce myself to Herzl. I placed myself entirely at his disposal. From that moment till the last days of his fruitful life, unhappily so prematurely ended, I remained in uninterrupted intercourse with our never-to-be-forgotten leader. To devote my strength to the continuance of this work I regarded as the task of my life. When, in the sad time after Herzl's death, the Presidency was offered to me, I was surprised and embarrassed. It was only out of a sense of duty that I accepted this high dignity."

References

- Medoff, Rafael; Waxman, Chaim I. (2009-09-28). The A to Z of Zionism. Scarecrow Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8108-7052-9.

- "Zionist leader dies". The New York Times. 1914-09-17. p. 9. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- Nahum Sokolow, History of Zionism: 1600-1918, Appendix LXXXIII, p.388-89 (1919)

Further reading

- Jüdisches Lexikon, Berlin 1927, vol. IV/2, columns 1492-1494

External links

- The personal papers of David Wolffsohn are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem