Debt-to-GDP ratio

In economics, the debt-to-GDP ratio is the ratio between a country's government debt (measured in units of currency) and its gross domestic product (GDP) (measured in units of currency per year). A low debt-to-GDP ratio indicates an economy that produces and sells goods and services is sufficient to pay back debts without incurring further debt.[1] Geopolitical and economic considerations – including interest rates, war, recessions, and other variables – influence the borrowing practices of a nation and the choice to incur further debt.[2] It should not be confused with a deficit-to-GDP ratio, which, for countries running budget deficits, measures a country's annual net fiscal loss in a given year (total expenditures minus total revenue, or the net change in debt per annum) as a percentage share of that country's GDP; for countries running budget surpluses, a surplus-to-GDP ratio measures a country's annual net fiscal gain as a share of that country's GDP.

Global statistics

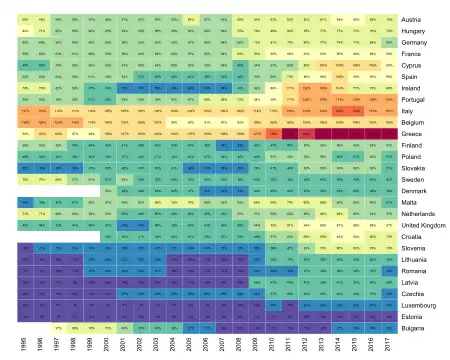

At the end of the 4th quarter of 2019, United States public debt-to-GDP ratio was at 106.7%.[3] The level of public debt in Japan was 246.1% of GDP, in China 46.7% and in India 61.8%, in 2017 according to the IMF,[4] while the public debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of the 2nd quarter of 2016 was at 70.1% of GDP in Germany, 89.1% in the United Kingdom, 98.2% in France and 135.5% in Italy, according to Eurostat.[5]

Two-thirds of US public debt is owned by US citizens, banks, corporations, and the Federal Reserve Bank;[6] approximately one-third of US public debt is held by foreign countries – particularly China and Japan. Conversely, less than 5% of Italian and Japanese public debt is held by foreign countries.

Particularly in macroeconomics, various debt-to-GDP ratios can be calculated. The most commonly used ratio is the government debt divided by the gross domestic product (GDP), which reflects the government's finances, while another common ratio is the total debt to GDP, which reflects the finances of the nation as a whole.

Changes

The change in debt-to-GDP is approximately "net change in debt as percentage of GDP"; for government debt, this is deficit or (surplus) as percentage of GDP.

This is only approximate as GDP changes from year to year, but generally, year-on-year GDP changes are small (say, 3%), and thus this is approximately correct.

However, in the presence of significant inflation, or particularly hyperinflation, GDP may increase rapidly in nominal terms; if debt is nominal, then its ratio to GDP will decrease rapidly. A period of deflation would have the opposite effect.

A government's debt-to-GDP ratio can be analysed by looking at how it changes or, in other words, how the debt is evolving over time:

The left hand side of the equation demonstrates the dynamics of the government's debt. is the debt-to-GDP at the end of the period t, and is the debt-to-GDP ratio at the end of the previous period (t−1). Hence, the left side of the equation shows the change in the debt-to-GDP ratio. The right hand side of the equation shows the causes of the government's debt. is the interest payments on the stock of debt as a ratio of GDP so far, and shows the primary deficit-to-GDP ratio.

If the government has the ability to print money, and therefore monetize the outstanding debt, the budget constraint becomes:

The term is the change in money balances (i.e. money growth). By printing money the government is able to increase nominal money balances to pay off the debt (consequently acting in the debt way that debt financing does, in order to balance the government's expenditures). However, the effect that an increase in nominal money balances has on seignorage is ambiguous, as while it increases the amount of money within the economy, the real value of each unit of money decreases due to inflationary effects. This inflationary effect from money printing is called an inflation tax.

Applications

Debt-to-GDP measures the financial leverage of an economy.

One of the Euro convergence criteria was that government debt-to-GDP should be below 60%.

The World Bank and the IMF hold that "a country can be said to achieve external debt sustainability if it can meet its current and future external debt service obligations in full, without recourse to debt rescheduling or the accumulation of arrears and without compromising growth". According to these two institutions, external debt sustainability can be obtained by a country "by bringing the net present value (NPV) of external public debt down to about 150 percent of a country's exports or 250 percent of a country's revenues".[7] High external debt is believed to have harmful effects on an economy.[8] The United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 17, an integral part of the 2030 Agenda has a target to address the external debt of highly indebted poor countries to reduce debt distress.[9]

In 2013 Herndon, Ash, and Pollin reviewed an influential, widely cited research paper entitled, "Growth in a Time of Debt",[10] by two Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff. Herndon, Ash and Pollin argued that "coding errors, selective exclusion of available data, and unconventional weighting of summary statistics lead to serious errors that inaccurately represent the relationship between public debt and GDP growth among 20 advanced economies in the post-war period".[11][12] Correcting these basic computational errors undermined the central claim of the book that too much debt causes recession.[13][14] Rogoff and Reinhardt claimed that their fundamental conclusions were accurate, despite the errors.[15][16]

There is a difference between external debt denominated in domestic currency, and external debt denominated in foreign currency. A nation can service external debt denominated in domestic currency by tax revenues, but to service foreign currency debt it has to convert tax revenues in the foreign exchange market to foreign currency, which puts downward pressure on the value of its currency.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Debt-to-GDP ratio. |

- Kenton, Will. "What the Debt-to-GDP Ratio Tells Us". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-09-22.

- "Budget Deficits and Interest Rates: What is the Link?". Federal Bank of St. Louis.

- Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product Federal Bank of St. Louis.

- International Monetary Fund: All countries Government finance>General government gross debt(Percent of GDP)

- Eurostat - News release: Government debt fell to 91.2% of GDP in euro area 24 October 2016.

- "America's Foreign Creditors". The New York Times. 19 July 2011.

- "The Challenge of Maintaining Long-Term External Debt Sustainability" (PDF). World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-04-08.

- Bivens, L. Josh (December 14, 2004). "Debt and the dollar" (PDF). EPI Issue Brief. Economic Policy Institute (203). p. 2, "US external debt obligations". Archived from the original (PDF) on December 17, 2004. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- "Goal 17 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs". sdgs.un.org. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- Krudy, Edward (18 April 2013). "How a student took on eminent economists on debt issue - and won". Reuters.

- Herndon, Thomas; Ash, Michael; Pollin, Robert (15 April 2013). "Does High Public Debt Consistently Stifle Economic Growth? A Critique of Reinhart and Rogoff" (PDF). Political Economy Research Institute, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Goldstein, Steve (April 16, 2013). "The spreadsheet error in Reinhart and Rogoff's famous paper on debt sustainability". MarketWatch. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- Alexander, Ruth (19 April 2013). "Reinhart, Rogoff... and Herndon: The student who caught out the profs". BBC News. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- "How Much Unemployment Was Caused by Reinhart and Rogoff's Arithmetic Mistake?". Center for Economic and Policy Research. April 16, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- Harding, Robin (16 April 2013). "Reinhart-Rogoff Initial Response". Financial Times.

- Inman, Phillip (April 17, 2013). "Rogoff and Reinhart defend their numbers". The Guardian. Retrieved April 18, 2013.