Deportation of Cambodian refugees from the United States

Deportation of Cambodian refugees from the United States refers to the refoulment (or involuntary removal) of Cambodian-Americans convicted of a common crime in the United States.[1] The overwhelming majority of these individuals in removal proceedings were admitted to the United States in the 1980s with their refugee family members after escaping from the Cambodian genocide, and have continuously spent decades in the United States as legal immigrants (potential U.S. nationals).[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

According to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), these Cambodian-Americans did not enter the United States with immigrant visas as lawful permanent residents but rather with special travel documents as refugees.[9][10][11] As such, they have been immunized against deportation since 1980 when the U.S. Congress enacted INA §§ 207 and 209, 8 U.S.C. §§ 1157 and 1159.[12][13][14] This legal finding is supported by latest precedents of all the U.S. courts of appeals and the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA),[15] which are binding on all immigration judges and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) officers.[16][17][18][19][20][21][4]

History

Cambodians escaping genocide and persecution

In 1975, the U.S. Congress and the Ford administration enacted the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act, which permitted about 130,000 natives of Cambodia, Laos, and South Vietnam to be admitted to the United States as refugees.[10][11] It is important to note that the Cambodian refugees were fleeing from genocide that was orchestrated by the communist Khmer Rouge government.[22]

In 1980, the U.S. Congress and the Carter administration enacted the Refugee Act, which approved 50,000 international refugees to be firmly-resettled in the United States each year. s.[23][24]

Firm resettlement of Cambodian refugees in the United States

Each year, from 1975 onward, groups of Cambodian refugee families lawfully entered the United States.[10][9] These families were issued by the U.S. Department of State special travel documents. After residing for at least one year, the then Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) adjusted their status to that of lawful permanent residents of the United States.[3] This process statutorily protected them against refoulment (forceful deportation) for lifetime.[12][15][13][25][14]

The Cambodian families were resettled in and around Long Beach, California, Lowell, Massachusetts, Lynn, Massachusetts, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[26][27] In 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court reminded all immigration officials that "once an alien gains admission to our country and begins to develop the ties that go with permanent residence, his constitutional status changes accordingly."[28] That opinion was issued after Congress and the Reagan administration resettled in the United States refugees from various countries.[29]

United States Congress provides statutory relief to Cambodian-Americans against removability

The INA historically stated that "[t]he term 'alien' means any person not a citizen or national of the United States."[30] The terms "inadmissible aliens" and "deportable aliens" are synonymous.[31]

In this regard, INA § 207(c), 8 U.S.C. § 1157(c), expressly provides the following:

The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking admission to the United States under this subsection, and the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] . . . with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.[32][33]

INA § 209, 8 U.S.C. § 1159, provides the following:

The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking adjustment of status under this section, and the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] . . . with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.[34][33]

In addition to the above provisions, INA § 212(h), 8 U.S.C. § 1182(h), provides the following:

The Attorney General may, in his discretion, waive the application of subparagraphs (A)(i)(I), (B), (D), and (E) of subsection (a)(2) . . . if. . . it is established to the satisfaction of the Attorney General that. . . the [crime] for which the alien is [removable] occurred more than 15 years before the date of the alien's application for a visa, admission, or adjustment of status, . . . the admission to the United States of such alien would not be contrary to the national welfare, safety, or security of the United States, and . . . the alien has been rehabilitated; or . . . in the case of an immigrant who is the spouse, parent, son, or daughter of a citizen of the United States or an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence if it is established to the satisfaction of the Attorney General that the alien's denial of admission would result in extreme hardship to the United States citizen or lawfully resident spouse, parent, son, or daughter of such alien. . . .[35][33][3]

The above legal finding "is consistent with one of the most basic interpretive canons, that a statute should be construed so that effect is given to all its provisions, so that no part will be inoperative or superfluous, void or insignificant."[36] Congress treated refugees (i.e., established victims of persecution who have absolutely no safe country) differently than all other aliens (who do have a safe country and are not victims of persecution).[11] If Congress wanted to treat refugees the same as all other aliens, it would have repealed §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c) instead of amending them in 1996 and then in 2005.[37] This demonstrates that it intentionally provided a special statutory and mandatory legal remedy to refugees. Under the well known Chevron doctrine, "[i]f the intent of Congress is clear, that is the end of the matter, for the court as well as the [Attorney General] must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress."[38]

It is also crucial to take notice that the penultimate provision of § 1182(h), where it repeatedly mentions the phrase under this subsection, obviously does not apply to any Cambodian-American requesting relief under §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c), or under the United Nations Convention against Torture (CAT).[39][14] In other words, that specific concluding statement of § 1182(h) only applies to aliens who were admitted to the United States as lawful permanent residents in accordance with Form I-130, Form I-140, Diversity Immigrant Visa, etc., and are requesting a waiver of inadmissibility prior to the statutory 15-year expiry-period of an aggravated felony conviction. See the section below: Introduction and amendment of the term "aggravated felony".

The Cambodian-Americans who were admitted as refugees in the 1980s are still refugees under the INA and international law because (1) they continue to be victims of persecution and (2) they have absolutely no safe country of permanent residence other than the United States.[11][40][29] This means that any Cambodian-American who has been convicted of any offense mentioned in § 1101(a)(43)(A) is not (and has never been) precluded from relief under §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c) or the CAT.[12][15][41][14] It has long been understood in the United States that whenever "Congress includes particular language in one section of a statute but omits it in another section of the same Act, it is generally presumed that Congress acts intentionally and purposely in the disparate inclusion or exclusion."[42]

The above provisions are in clear harmony with each other and the overall law of the United States, including with international law.[19] Secondly, providing relief under §§ 1157(c)(3) and 1159(c) or the CAT is not discretionary but statutory and mandatory,[43][44][14] and the above provisions all involve "legal claims" (i.e., constitutional claims or questions of law). As such, federal judges are fully empowered to review these "legal claims" at any time, especially in a case involving exceptional circumstances.[45][46][47][48][49][50] The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit recently reaffirmed this by stating the following:

[W]e have not specifically addressed whether we have jurisdiction to review the Board's denial of a motion to reopen sua sponte for the limited purpose of determining whether the Board based its decision on legal or constitutional error. Several circuits have held that courts of appeal do have such limited jurisdiction . . . we agree with those decisions.[51]

Expansion of the definition of "nationals but not citizens of the United States"

In 1986, less than a year before the CAT became effective, Congress expressly and intentionally expanded the definition of "nationals but not citizens of the United States" by adding paragraph (4) to 8 U.S.C. § 1408, which plainly states that:

the following shall be nationals, but not citizens, of the United States at birth: .... (4) A person born outside the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is an alien, and the other a national, but not a citizen, of the United States who, prior to the birth of such person, was physically present in the United States or its outlying possessions for a period or periods totaling not less than seven years in any continuous period of ten years—(A) during which the national parent was not outside the United States or its outlying possessions for a continuous period of more than one year, and (B) at least five years of which were after attaining the age of fourteen years.[52][43]

The natural reading of § 1408(4) demonstrates that it was not exclusively written for the 55,000 American Samoans but for all people who statutorily and manifestly qualify as "nationals but not citizens of the United States."[52][53][54] This means that any Cambodian-American who can show by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets (or at any time has met) the requirements of 8 U.S.C. §§ 1408(4) and 1436 is plainly and unambiguously a "national but not a citizen of the United States."[49][2] Such person must never be labelled or treated as an alien, especially after demonstrating that he or she has continuously resided in the United States for at least 10 years without committing (in such 10 years) any offense that triggers removability.[55][56] "Deprivation of [nationality]—particularly American [nationality], which is one of the most valuable rights in the world today—has grave practical consequences."[21][17][18][57][19][20][4][58][59]

Introduction and amendment of the term "aggravated felony"

In 1988, Congress introduced the term "aggravated felony" by defining it under 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a),[60] which was amended several times over the years. As of September 30, 1996, an "aggravated felony" only applies to convictions "for which the term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[41][61][35][36][54][48] After these "15 years" successfully elapse (i.e., without sustaining another aggravated felony conviction), a long-time lawful permanent resident (LPR) automatically becomes entitled to both cancellation of removal and a waiver of inadmissibility.[59] He or she may (at any time and from anywhere in the world[62][63][45][46]) request these popular immigration benefits depending on whichever is more applicable or easiest to obtain.[13][64] It is important to note that a court-imposed suspended sentence counts as "term of imprisonment" and must be added to the above 15 years,[65] and it makes no difference if the aggravated felony conviction was entered in American Samoa, Australia, Cambodia, Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom, the United States, or in any other country or place in the world.[41][36][54]

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act

In February 1995, U.S. President Bill Clinton issued an important directive in which he expressly stated the following:

Our efforts to combat illegal immigration must not violate the privacy and civil rights of legal immigrants and U.S. citizens. Therefore, I direct the Attorney General, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and other relevant Administration officials to vigorously protect our citizens and legal immigrants from immigration-related instances of discrimination and harassment. All illegal immigration enforcement measures shall be taken with due regard for the basic human rights of individuals and in accordance with our obligations under applicable international agreements. (emphasis added).[4][43]

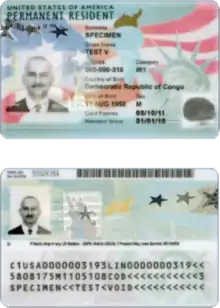

On September 30, 1996, President Clinton signed into law the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which is particularly aimed at combating illegal immigration to the United States.[37] But despite what President Clinton said in the above directive, some plainly incompetent immigration officers began deporting long-time legal immigrants (i.e., potential Americans),[59][12] who have permanent resident cards, Social Security numbers, driver's licenses, state ID cards, bank accounts, credit cards, insurances, etc. They own homes, businesses, vehicles and other properties in the United States under their names. Such people statutorily qualify as "nationals of the United States" after continuously residing in the United States for at least 10 years without committing (in such 10 years) any offense that triggers removability.[52][13] This appears to be the reason why the permanent resident card (green card) is valid for 10 years. It was expected that all Cambodian refugees in the United States would equally obtain U.S. citizenship within 10 years from the date of their first lawful entry,[10][66] but if that was unachievable then they would statutorily become "nationals but not citizens of the United States" after such 10 years successfully elapse.[54] Anything to the contrary will lead to "deprivation of rights under color of law," which is a federal crime that entails capital punishment for the perpetrator(s).[17][18][57][19][20][21][4][55][58][56]

The Cambodian refugees in removal proceedings have already "been lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States" by the Attorney General,[3][12][15]

"Only aliens are subject to removal."[67] As mentioned above, the terms "inadmissible aliens" and "deportable aliens" are synonymous.[31] It is common knowledge that these aliens mainly refer to the INA violators among the 75 million foreign nationals who are admitted each year as guests,[68][69] the 12 million or so illegal aliens,[70] and the INA violators among the 400,000 foreign nationals who possess the temporary protected status (TPS).[71] A lawful permanent resident (legal immigrant) can either be an alien or a national of the United States (American), which requires a case-by-case analysis and depends mainly on the number of continuous years he or she has spent in the United States as a green card holder.[49][2][72]

The INA makes clear that any alien or any "national but not a citizen of the United States" who has been convicted of any aggravated felony, whether the aggravated felony was committed inside or outside the United States, is ineligible for citizenship of the United States if his or her "term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[41][73][74] However, unlike a "national but not a citizen of the United States," an alien who has been convicted of any aggravated felony is removable if his or her "term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years."[41][61][36][54][48] In other words, such alien cannot:

- be admitted to the United States prior to being granted a waiver of inadmissibility or cancellation of removal by any authorized U.S. immigration official,[13][12][15][64] or "a full and unconditional pardon by the President of the United States or by the Governor of any of the several States."[75]

- have his or her removal proceedings terminated without a written legal order issued by any immigration official,[76] or an injunction issued by any federal judge.[47][50][77]

- obtain asylum in the United States unless he or she was previously admitted to the United States as a refugee,[12][15] or his or her aggravated felony was shown not to be a particularly serious crime.[78] An alien convicted of a particularly serious crime may still receive asylum, so long as he or she is not "a danger to the community of the United States,"[79] or at minimum deferral of removal under the CAT.[14] It must be added that granting protection under the CAT is statutory and mandatory.[44][14]

- obtain adjustment of status unless he or she was previously admitted to the United States as a refugee.[12][15]

- obtain voluntary departure.[80]

Challenging an aggravated felony charge

An "order of deportation" may be reviewed at any time by any immigration judge or any BIA member and finally by any authorized federal judge.[45] Particular cases, especially those that were adjudicated in any U.S. district court prior to the enactment of the Real ID Act of 2005, can be reopened under Rule 60 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.[46] The review of the order does not require the alien (or the American) to remain in the United States. It can be requested from anywhere in the world via mail and/or electronic court filing (ECF),[63] and the case can be filed in any court the alien (or the American) finds appropriate.[59]

Every United States nationality claim, illegal deportation claim, and CAT or asylum claim is adjudicated under 8 U.S.C. §§ 1252(a)(4), 1252(b)(4), 1252(b)(5), 1252(d) and 1252(f)(2). When these specific provisions are invoked, all other contrary provisions of law, especially § 1252(b)(1) and Stone v. INS, 514 U.S. 386, 405 (1995) (case obviously decided prior to IIRIRA of 1996, which materially changed the old "judicial review provisions of the INA"),[37] must be disregarded because the above three claims manifestly constitute exceptional circumstances.[48][46][49][2][47][50][29] The Supreme Court has pointed out in 2009 that "the context surrounding IIRIRA's enactment suggests that § 1252(f)(2) was an important—not a superfluous—statutory provision."[81] In this regard, Congress has stating the following:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be subject to specified criminal penalties.[82][17][18][57][19][20][4][21]

According to § 1252(f)(1), "no court (other than the Supreme Court)" is authorized to determine which two or more people in removal proceedings should be recognized as nationals of the United States (Americans).[47] This includes parents and children or relatives.[52][49] The remaining courts, however, are fully empowered pursuant to §§ 1252(b)(5) and 1252(f)(2) to, inter alia, issue an injunction to terminate any persons removal proceedings; return any previously removed person to the United States; and/or to confer United States nationality upon any person (but only using a case-by-case analysis).[47][50][49] In addition to that, under 8 CFR 239.2, any officer mentioned in 8 CFR 239.1 may at any time move to terminate the case of any person who turns out to be a national of the United States or one who is clearly not "removable" under the INA.[31][76] The burden of proof is on the alien (or the American) to establish a prima facie entitlement to re-admission after the deportation has been completed.[62][45]

Number of Cambodian-Americans physically removed from the United States

Between the years of 2003 and 2016 (per ICE), approximately 750 Cambodian-Americans were physically removed from the United States.[5] Of these, at least 12 have reportedly died (some from suicide or drug overdose) and another 17 are in Cambodian prison.[26] ICE data shows that deportation of Cambodian-Americans averaged 41 per year from 2001 through 2010, increasing to 96 in 2011 and 90 in 2012.[26] As of 2017, nearly 1,900 Cambodian-Americans have final orders of removal, meaning they can be deported from the United States at any time.[5]

Deported Cambodian-Americans are typically young men in their twenties and thirties who were either born inside Cambodia or in refugee camps in neighboring Thailand.[6][1][7][83] Most were admitted to the United States as small children of refugee families, members of the so-called 1.5 generation.[5] A 2005 survey by one immigrant advocacy organization showed that the Cambodian-American deportees had continuously resided in the United States for an average of 20 years.[84] Many of those deported after 2005 have continuously resided in the United States for over 30 years.[6][85] As such, they received most or all of their education in the United States, often speak Khmer language very poorly.[86] Many of the Cambodian-American deportees either have not visited Cambodia in decades or saw it for the first time after their deportation.[26][6][52][2][49]

Reason for deportation

Most Cambodian-Americans were deported for committing a common crime in the United States.[87] Several of them violated a firearm law.[13][10][23] Congress clarified this in 1996 and it was settled by the BIA in a March 2000 en banc decision,[13] which has since been binding on all immigration judges and DHS officers.[16]

Notable Cambodian-American deportees

The following is an incomplete list of Cambodian-Americans who were physically removed from the United States to Cambodia:

- Chally Dang, born in a refugee camp in Thailand but grew up in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He was convicted of assault and related charges in 1998 (around the age of 15), which was his very first conviction. He was refouled (involuntarily deported) to Cambodia in June 2011. His deportation separated him from his parents, spouse, and children.[88][1]

- Tuy Sobil, a deported Cambodian-American who operates Tiny Toones, which was established as a breakdancing ("b-boying") for poor urban Cambodian children. Sobil grew up in Long Beach, California, where he was exposed to b-boying and danced for four years after seeing it in the local parks. His family immigrated to the United States as refugees in 1980, when he was an infant. He was convicted of a California robbery charge (around the age of 18). As a result of that conviction, he was refouled (involuntarily deported) to Cambodia in 2004.[8][89]

- Kosal Khiev, spoken word artist, was deported in 2011 after serving 16 years in California prisons for his involvement in a gang-related shooting.[90]

Organizations helping Cambodian-American deportees

- Returnee Integration Support Center in Phnom Penh is dedicated to helping deportees obtain documents, housing, jobs, and drug treatment. It was established by Rev. Bill Herod, a minister from the U.S. state of Indiana, who has long resided in Cambodia.[26][91]

Demonstrations

A number of demonstrations have been witnessed in several U.S. cities over the deportation of Cambodian-Americans.[92]

See also

References

This article in most part is based on law of the United States, including statutory and latest published case law.

- "NBC Asian America Presents: Deported". NBC. March 16, 2017. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Ricketts v. Att'y Gen., 897 F.3d 491 (3d Cir. 2018) ("When an alien faces removal under the Immigration and Nationality Act, one potential defense is that the alien is not an alien at all but is actually a national of the United States."); Mohammadi v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 782 F.3d 9, 15 (D.C. Cir. 2015) ("The sole such statutory provision that presently confers United States nationality upon non-citizens is 8 U.S.C. § 1408."); Matter of Navas-Acosta, 23 I&N Dec. 586, 587 (BIA 2003) ("If Congress had intended nationality to attach at some point before the naturalization process is complete, we believe it would have said so."); 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("A person not a citizen who owes permanent allegiance to the United States, and who is otherwise qualified, may, if he becomes a resident of any State, be naturalized upon compliance with the applicable requirements of this subchapter...."); Saliba v. Att'y Gen., 828 F.3d 182, 189 (3d Cir. 2016) ("Significantly, an applicant for naturalization has the burden of proving 'by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets all of the requirements for naturalization.'"); ("The term 'naturalization' means the conferring of [United States nationality] upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.") (emphasis added); see also In re Petition of Haniatakis, 376 F.2d 728 (3d Cir. 1967); In re Sotos' Petition, 221 F. Supp. 145 (W.D. Pa. 1963).

- ("The term 'lawfully admitted for permanent residence' means the status of having been lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States as an immigrant....").

- "60 FR 7885: ANTI-DISCRIMINATION" (PDF). U.S. Government Publishing Office. February 10, 1995. p. 7888. Retrieved 2018-09-26. See also Zuniga-Perez v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-996, p.11 (2d Cir. July 25, 2018) ("The Constitution protects both citizens and non‐citizens.") (emphasis added).

- Federis, Marnette (March 10, 2018). "After deportation, a family from Wisconsin will start anew in Cambodia". Public Radio International (PRI). Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- McCormick, Andrew (August 25, 2017). "Strangers in their homeland: the Khmerican Cambodians Trump deported". South China Morning Post (SCMP). Retrieved 2018-09-26.

For many deportees, the United States had been home for decades. Now, they struggle to adjust to life in the country of their birth

- Barros, Aline (December 7, 2017). "US Set to Deport 70 Cambodians". Voice of America (VoA). Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- Mydans, Seth (November 30, 2008). "Californian finds new life in Cambodia". New York Times. Retrieved September 26, 2018.

- Smriko v. Ashcroft, 387 F.3d 279, 287 (3d Cir. 2004) (explaining that the idea of refugees being admitted to the United States as lawful permanent residents was intentionally rejected by the U.S. Congressional Conference Committee); H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 96-781, at 21 (1980), reprinted in 1980 U.S.C.C.A.N. 160, 162.

- ("The terms 'admission' and 'admitted' mean, with respect to an alien, the lawful entry of the alien into the United States after inspection and authorization by an immigration officer.") (emphasis added); Matter of D-K-, 25 I&N Dec. 761, 765-66 (BIA 2012).

- ("The term 'refugee' means ... any person who is outside any country of such person's nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable ... to return to, and is unable ... to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion....") (emphasis added); Mashiri v. Ashcroft, 383 F.3d 1112, 1120 (9th Cir. 2004) ("Persecution may be emotional or psychological, as well as physical."); Matter of B-R-, 26 I&N Dec. 119, 122 (BIA 2013) ("The core regulatory purpose of asylum . . . is . . . to protect refugees with nowhere else to turn.") (brackets and internal quotation marks omitted).

- Matter of H-N-, 22 I&N Dec. 1039, 1040-45 (BIA 1999) (en banc) (case of a female Cambodian-American who was convicted of a particularly serious crime but "the Immigration Judge found [her] eligible for a waiver of inadmissibility, as well as for adjustment of status, and he granted her this relief from removal."); Matter of Jean, 23 I&N Dec. 373, 381 (A.G. 2002) ("Aliens, like the respondent, who have been admitted (or conditionally admitted) into the United States as refugees can seek an adjustment of status only under INA § 209."); INA § 209(c), ("The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) of this title shall not be applicable to any alien seeking adjustment of status under this section, and the Secretary of Homeland Security or the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182] ... with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.") (emphasis added); Nguyen v. Chertoff, 501 F.3d 107, 109-10 (2d Cir. 2007) (petition granted of a Vietnamese-American convicted of a particularly serious crime); City of Cleburne v. Cleburne Living Center, Inc., 473 U.S. 432, 439 (1985) ("The Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment commands that ... all persons similarly situated should be treated alike.").

- (eff. April 1, 1997) (stating that an LPR, especially a wrongfully deported LPR, is permitted to reenter the United States by any means whatsoever, including with a grant of "relief under section 1182(h) or 1229b(a) of this title....") (emphasis added); accord United States v. Aguilera-Rios, 769 F.3d 626, 628-29 (9th Cir. 2014) ("[Petitioner] was convicted of a California firearms offense, removed from the United States on the basis of that conviction, and, when he returned to the country, tried and convicted of illegal reentry under 8 U.S.C. § 1326. He contends that his prior removal order was invalid because his conviction ... was not a categorical match for the Immigration and Nationality Act's ('INA') firearms offense. We agree that he was not originally removable as charged, and so could not be convicted of illegal reentry."); see also Matter of Campos-Torres, 22 I&N Dec. 1289 (BIA 2000) (en banc) (A firearms offense that renders an alien removable under section 237(a)(2)(C) of the Act, (Supp. II 1996), is not one 'referred to in section 212(a)(2)' and thus does not stop the further accrual of continuous residence or continuous physical presence for purposes of establishing eligibility for cancellation of removal."); Vartelas v. Holder, 566 U.S. 257, 262 (2012).

- Anwari v. Attorney General of the U.S., Nos. 18-1505 & 18-2291, p.6 (3rd Cir. Nov. 6, 2018); see also Matter of Y-L-, A-G- & R-S-R-, 23 I&N Dec. 270, 279 (A.G. 2002) ("Although the respondents are statutorily ineligible for withholding of removal by virtue of their convictions for 'particularly serious crimes,' the regulations implementing the Convention Against Torture allow them to obtain a deferral of removal notwithstanding the prior criminal offenses if they can establish that they are 'entitled to protection' under the Convention."); ("Claims under the United Nations Convention").

- Matter of J-H-J-, 26 I&N Dec. 563 (BIA 2015) (collecting court cases) ("An alien who adjusted status in the United States, and who has not entered as a lawful permanent resident, is not barred from establishing eligibility for a waiver of inadmissibility under section 212(h) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, (2012), as a result of an aggravated felony conviction.") (emphasis added); see also De Leon v. Lynch, 808 F.3d 1224, 1232 (10th Cir. 2015) ("[Petitioner] next claims that even if he is removable, he should nevertheless have been afforded the opportunity to apply for a waiver under . Under controlling precedent from our court and the BIA's recent decision in Matter of J–H–J–, he is correct.") (emphasis added).

- "Board of Immigration Appeals". U.S. Dept. of Justice. March 16, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

BIA decisions are binding on all DHS officers and immigration judges unless modified or overruled by the Attorney General or a federal court.

See also 8 CFR 1003.1(g) ("Decisions as precedents."). - "Deprivation Of Rights Under Color Of Law". U.S. Dept. of Justice (DOJ). August 6, 2015. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a crime for a person acting under color of any law to willfully deprive a person of a right or privilege protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. For the purpose of Section 242, acts under 'color of law' include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of that official's lawful authority, if the acts are done while the official is purporting to or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties. Persons acting under color of law within the meaning of this statute include police officers, prisons guards and other law enforcement officials, as well as judges, care providers in public health facilities, and others who are acting as public officials. It is not necessary that the crime be motivated by animus toward the race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin of the victim. The offense is punishable by a range of imprisonment up to a life term, or the death penalty, depending upon the circumstances of the crime, and the resulting injury, if any.

(emphasis added). - 18 U.S.C. §§ 241–249; United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264 (1997) ("Section 242 is a Reconstruction Era civil rights statute making it criminal to act (1) 'willfully' and (2) under color of law (3) to deprive a person of rights protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."); United States v. Acosta, 470 F.3d 132, 136 (2d Cir. 2006) (holding that 18 U.S.C. §§ 241 and 242 are "crimes of violence"); see also 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981–1985 et seq.; Rodriguez v. Swartz, 899 F.3d 719 (9th Cir. 2018) ("A U.S. Border Patrol agent standing on American soil shot and killed a teenage Mexican citizen who was walking down a street in Mexico."); Ziglar v. Abbasi, 582 U.S. ___ (2017) (mistreating immigration detainees); Hope v. Pelzer, 536 U.S. 730, 736-37 (2002) (mistreating prisoners).

- "Article 16". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

[The United States] shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article I, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

(emphasis added). - "Chapter 11 - Foreign Policy: Senate OKs Ratification of Torture Treaty" (46th ed.). CQ Press. 1990. pp. 806–7. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

The three other reservations, also crafted with the help and approval of the Bush administration, did the following: Limited the definition of 'cruel, inhuman or degrading' treatment to cruel and unusual punishment as defined under the Fifth, Eighth and 14th Amendments to the Constitution....

(emphasis added). - Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 160 (1963) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted); see also Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 395 (2012) ("Perceived mistreatment of aliens in the United States may lead to harmful reciprocal treatment of American citizens abroad.").

- "Cambodia: Khmer Rouge leaders guilty of genocide, court rules". Al Jazeera. November 16, 2018. Retrieved 2018-11-16.

Verdict after years of trial is first time any Khmer Rouge leaders were found guilty of genocide for 1975-79 terror.

- Matter of D-X- & Y-Z-, 25 I&N Dec. 664, 666 (BIA 2012) ("It is well settled that an alien is not faulted for using fraudulent documents to escape persecution and seek asylum in the United States."); see also ; .

- United States v. Otherson, 637 F.2d 1276 (9th Cir. 1980), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 840 (1981), (U.S. immigration officer convicted of serious federal crimes); see also United States v. Maravilla, 907 F.2d 216 (1st Cir. 1990) (U.S. immigration officers kidnapped, robbed and murdered a visiting foreign businessman).

- Matter of Z-Z-O-, 26 I&N Dec. 586 (BIA 2015) ("Whether an asylum applicant has an objectively reasonable fear of persecution based on the events that the Immigration Judge found may occur upon the applicant's return to the country of removal is a legal determination that is subject to de novo review.").

- "Cambodian-Americans confronting deportation". Olesia Plokhii and Tom Mashberg. Boston Globe. January 27, 2013. Retrieved 2014-05-10.

- Pert, Charlotte Pert (June 26, 2016). "Torn families of Cambodian refugees deported from US". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21, 32 (1982).

- See generally Hanna v. Holder, 740 F.3d 379, 393-97 (6th Cir. 2014) (firm resettlement); Matter of A-G-G-, 25 I&N Dec. 486 (BIA 2011) (same).

- (emphasis added); see also ("The term 'national of the United States' means (A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States.") (emphasis added); Ricketts v. Att'y Gen., 897 F.3d 491, 493-94 n.3 (3d Cir. 2018) ("Citizenship and nationality are not synonymous."); ("The term 'permanent' means a relationship of continuing or lasting nature, as distinguished from temporary, but a relationship may be permanent even though it is one that may be dissolved eventually at the instance either of the United States or of the individual, in accordance with law."); ("The term 'residence' means the place of general abode; the place of general abode of a person means his principal, actual dwelling place in fact, without regard to intent."); Black's Law Dictionary at p.87 (9th ed., 2009) (defining the term "permanent allegiance" as "[t]he lasting allegiance owed to [the United States] by its citizens or [permanent resident]s.") (emphasis added).

- ("The term 'removable' means—(A) in the case of an alien not admitted to the United States, that the alien is inadmissible under section 1182 of this title, or (B) in the case of an alien admitted to the United States, that the alien is deportable under section 1227 of this title."); see also Tima v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-4199, p.11 (3d Cir. Sept. 6, 2018) ("Section 1227 defines '[d]eportable aliens,' a synonym for removable aliens.... So § 1227(a)(1) piggybacks on § 1182(a) by treating grounds of inadmissibility as grounds for removal as well."); Galindo v. Sessions, 897 F.3d 894, ___, No. 17-1253, p.4-5 (7th Cir. 2018).

- (emphasis added).

- Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 855-56 (2018) (Justice Thomas concurring) ("The term 'or' is almost always disjunctive, that is, the [phrase]s it connects are to be given separate meanings.").

- (emphasis added).

- (emphasis added).

- Rubin v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 583 U.S. ___ (2018) (Slip Opinion at 10) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); see also Matter of Song, 27 I&N Dec. 488, 492 (BIA 2018) ("Because the language of both the statute and the regulations is plain and unambiguous, we are bound to follow it."); Matter of Figueroa, 25 I&N Dec. 596, 598 (BIA 2011) ("When interpreting statutes and regulations, we look first to the plain meaning of the language and are required to give effect to unambiguously expressed intent. Executive intent is presumed to be expressed by the ordinary meaning of the words used. We also construe a statute or regulation to give effect to all of its provisions.") (citations omitted); Lamie v. United States Trustee, 540 U.S. 526, 534 (2004); TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 31 (2001) ("It is a cardinal principle of statutory construction that a statute ought, upon the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be superfluous, void, or insignificant.") (internal quotation marks omitted); United States v. Menasche, 348 U.S. 528, 538-539 (1955) ("It is our duty to give effect, if possible, to every clause and word of a statute." (internal quotation marks omitted); NLRB v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 30 (1937) ("The cardinal principle of statutory construction is to save and not to destroy. We have repeatedly held that as between two possible interpretations of a statute, by one of which it would be unconstitutional and by the other valid, our plain duty is to adopt that which will save the act. Even to avoid a serious doubt the rule is the same.").

- Othi v. Holder, 734 F.3d 259, 264-65 (4th Cir. 2013) ("In 1996, Congress 'made major changes to immigration law' via IIRIRA.... These IIRIRA changes became effective on April 1, 1997.").

- Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 842-43 (1984).

- Tima v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-4199, p.8 (3d Cir. Sept. 6, 2018) ("Congressional drafting manuals instruct drafters to break statutory sections down into subsections, paragraphs, subparagraphs, clauses, and subclauses.").

- See generally Matter of Smriko, 23 I&N Dec. 836 (BIA 2005) (a cursory opinion of a three-member panel blatantly persecuting refugees and depriving them of rights); Maiwand v. Gonzales, 501 F.3d 101, 106-07 (2d Cir. 2007) (same); Romanishyn v. Att'y Gen., 455 F.3d 175 (3d Cir. 2006) (same); Kaganovich v. Gonzales, F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2006) (same).

- ("The term [aggravated felony] applies to an offense described in this paragraph whether in violation of Federal or State law and applies to such an offense in violation of the law of a foreign country for which the term of imprisonment was completed within the previous 15 years.") (emphasis added); Matter of Vasquez-Muniz, 23 I&N Dec. 207, 211 (BIA 2002) (en banc) ("This penultimate sentence, governing the enumeration of crimes in section 101(a)(43) of the Act, refers the reader to all of the crimes 'described in' the aggravated felony provision."); Luna Torres v. Lynch, 578 U.S. ___, 136 S.Ct. 1623 (2016) ("The whole point of § 1101(a)(43)'s penultimate sentence is to make clear that a listed offense should lead to swift removal, no matter whether it violates federal, state, or foreign law."); see also 8 CFR 1001.1(t) ("The term aggravated felony means a crime (or a conspiracy or attempt to commit a crime) described in section 101(a)(43) of the Act. This definition is applicable to any proceeding, application, custody determination, or adjudication pending on or after September 30, 1996, but shall apply under section 276(b) of the Act only to violations of section 276(a) of the Act occurring on or after that date.") (emphasis added).

- United States v. Wong Kim Bo, 472 F.2d 720, 722 (5th Cir. 1972); see also United States v. Wooten, 688 F.2d 941, 950 (4th Cir. 1982).

- Alabama v. Bozeman, 533 U.S. 146, 153 (2001) ("The word 'shall' is ordinarily the language of command.") (internal quotation marks omitted).

- (stating that "the authority for which is specified under this subchapter to be in the discretion of the Attorney General or the Secretary of Homeland Security, other than the granting of relief under section 1158(a)....") (emphasis added).

- ; see generally Reyes Mata v. Lynch, 576 U.S. ___, ___, 135 S.Ct. 2150, 1253 (2015); Avalos-Suarez v. Whitaker, No. 16-72773 (9th Cir. Nov. 16, 2018) (unpublished) (case remanded to the BIA which involves a legal claim over a 1993 order of deportation); Nassiri v. Sessions, No. 16-60718 (5th Cir. Dec. 14, 2017); Alimbaev v. Att'y, 872 F.3d 188, 194 (3d Cir. 2017); Agonafer v. Sessions, 859 F.3d 1198, 1202-03 (9th Cir. 2017); In re Baig, A043-589-486 (BIA Jan. 26, 2017) (unpublished three-member panel decision); In re Cisneros-Ramirez, A 090-442-154 (BIA Aug. 9, 2016) (same); In re Contreras-Largaespada, A014-701-083 (BIA Feb. 12, 2016) (same); In re Wagner Aneudis Martinez, A043 447 800 (BIA Jan. 12, 2016) (same); In re Vikramjeet Sidhu, A044 238 062 (BIA Nov. 30, 2011) (same); accord Matter of A-N- & R-M-N-, 22 I&N Dec. 953 (BIA 1999) (en banc); Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281, 285 (BIA 1998) (en banc); Matter of JJ-, 21 I&N Dec. 976 (BIA 1997) (en banc).

- United States v. Bueno-Sierra, No. 17-12418, p.6-7 (6th Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) ("Rule 60(b)(1) through (5) permits a district court to set aside an otherwise final judgment on a number of specific grounds, such as mistake, newly discovered evidence, an opposing party’s fraud, or a void or satisfied judgment. Rule 60(b)(6), the catch-all provision, authorizes a judgment to be set aside for 'any other reason that justifies relief.' Rule 60(d)(3) provides that Rule 60 does not limit a district court’s power to 'set aside a judgment for fraud on the court.'") (citations omitted) (unpublished); Herring v. United States, 424 F.3d 384, 386-87 (3d Cir. 2005) ("In order to meet the necessarily demanding standard for proof of fraud upon the court we conclude that there must be: (1) an intentional fraud; (2) by an officer of the court; (3) which is directed at the court itself; and (4) in fact deceives the court."); 18 U.S.C. § 371; 18 U.S.C. § 1001 (court employees (including judges and clerks) have no immunity from prosecution under this section of law); Luna v. Bell, 887 F.3d 290, 294 (6th Cir. 2018) ("Under Rule 60(b)(2), a party may request relief because of 'newly discovered evidence.'"); United States v. Handy, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 18-3086, p.5-6 (10th Cir. July 18, 2018) ("Rule 60(b)(4) provides relief from void judgments, which are legal nullities.... [W]hen Rule 60(b)(4) is applicable, relief is not a discretionary matter; it is mandatory. And the rule is not subject to any time limitation.") (citations, brackets, and internal quotation marks omitted); Mattis v. Vaughn, Civil Action No. 99-6533 (E.D. Pa. June 4, 2018); accord Satterfield v. Dist. Att'y of Phila., 872 F.3d 152, 164 (3d Cir. 2017) ("The fact that . . . proceeding ended a decade ago should not preclude him from obtaining relief under Rule 60(b) if the court concludes that he has raised a colorable claim that he meets this threshold actual-innocence standard ...."); see also United States v. Olano, 507 U.S. 725, 736 (1993) ("In our collateral review jurisprudence, the term 'miscarriage of justice' means that the defendant is actually innocent.... The court of appeals should no doubt correct a plain forfeited error that causes the conviction or sentencing of an actually innocent defendant....") (citations omitted); Davis v. United States, 417 U.S. 333, 346-47 (1974) (regarding "miscarriage of justice" and "exceptional circumstances"); Gonzalez-Cantu v. Sessions, 866 F.3d 302, 306 (5th Cir. 2017) (same); Pacheco-Miranda v. Sessions, No. 14-70296 (9th Cir. Aug. 11, 2017) (same).

- Jennings v. Rodriguez, 583 U.S. ___, 138 S.Ct. 830, 851 (2018); Wheaton College v. Burwell, 134 S.Ct. 2806, 2810-11 (2014) ("Under our precedents, an injunction is appropriate only if (1) it is necessary or appropriate in aid of our jurisdiction, and (2) the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear.") (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); Lux v. Rodrigues, 561 U.S. 1306, 1308 (2010); Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 74 (2001) (stating that "injunctive relief has long been recognized as the proper means for preventing entities from acting unconstitutionally."); Alli v. Decker, 650 F.3d 1007, 1010-11 (3d Cir. 2011) (same); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482-85 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (same); see also ("Limitation on collateral attack on underlying deportation order").

- NLRB v. SW General, Inc., 580 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 929, 939 (2017) ("The ordinary meaning of 'notwithstanding' is 'in spite of,' or 'without prevention or obstruction from or by.' In statutes, the [notwithstanding any other provision of law] 'shows which provision prevails in the event of a clash.'"); In re JMC Telecom LLC, 416 B.R. 738, 743 (C.D. Cal. 2009) (explaining that "the phrase 'notwithstanding any other provision of law' expresses the legislative intent to override all contrary statutory and decisional law.") (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted) (emphasis added); see also In re Partida, 862 F.3d 909, 912 (9th Cir. 2017) ("That is the function and purpose of the 'notwithstanding' clause."); Drakes Bay Oyster Co. v. Jewell, 747 F.3d 1073, 1083 (9th Cir. 2014) ("As a general matter, 'notwithstanding' clauses nullify conflicting provisions of law."); Jones v. United States, No. 08-645C, p.4-5 (Fed. Cl. Sep. 14, 2009); Kucana v. Holder, 558 U.S. 233, 238-39 n.1 (2010); Cisneros v. Alpine Ridge Group, 508 U.S. 10, 18 (1993) (collecting court cases).

- Khalid v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16‐3480, p.6 (2d Cir. Sept. 13, 2018) ("[Petitioner] is a U.S. citizen and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) must terminate removal proceedings against him.") (oral argument (audio)); Jaen v. Sessions, 899 F.3d 182 (2d Cir. 2018) (same); Anderson v. Holder, 673 F.3d 1089, 1092 (9th Cir. 2012) (same); Dent v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-15662, p.10-11 (9th Cir. Aug. 17, 2018) ("An individual has third-party standing when [(1)] the party asserting the right has a close relationship with the person who possesses the right [and (2)] there is a hindrance to the possessor's ability to protect his own interests.") (quoting Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 582 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 1678, 1689 (2017)) (internal quotation marks omitted); Gonzalez-Alarcon v. Macias, 884 F.3d 1266, 1270 (10th Cir. 2018); Hammond v. Sessions, No. 16-3013, p.2-3 (2d Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) ("It is undisputed that Hammond's June 2016 motion to reconsider was untimely because his removal order became final in 2003.... Here, reconsideration was available only under the BIA's sua sponte authority. 8 CFR 1003.2(a). Despite this procedural posture, we retain jurisdiction to review Hammond's U.S. [nationality] claim."); accord Duarte-Ceri v. Holder, 630 F.3d 83, 87 (2d Cir. 2010) ("Duarte's legal claim encounters no jurisdictional obstacle because the Executive Branch has no authority to remove a [national of the United States]."); 8 CFR 239.2; see also Yith v. Nielsen, 881 F.3d 1155, 1159 (9th Cir. 2018) ("Once applicants have exhausted administrative remedies, they may appeal to a district court."); ("Request for hearing before district court").

- Singh v. USCIS, 878 F.3d 441, 443 (2d Cir. 2017) ("The government conceded that Singh's removal was improper.... Consequently, in May 2007, Singh was temporarily paroled back into the United States by the Attorney General, who exercised his discretion to grant temporary parole to certain aliens."); Orabi v. Att'y Gen., 738 F.3d 535, 543 (3d Cir. 2014) ("The judgment of the BIA will therefore be reversed, with instructions that the Government... be directed to return Orabi to the United States...."); Avalos-Palma v. United States, No. 13-5481 (FLW), 2014 WL 3524758, p.3 (D.N.J. July 16, 2014) ("On June 2, 2012, approximately 42 months after the improper deportation, ICE agents effectuated Avalos-Palma's return to the United States."); In re Vikramjeet Sidhu, A044 238 062, at 1-2 (BIA Nov. 30, 2011) ("As related in his brief on appeal, the respondent was physically removed from the United States in June 2004, but subsequently returned to this country under a grant of humanitarian parole.... Accordingly, the proceedings will be terminated.") (three-member panel).

- Bonilla v. Lynch, 840 F.3d 575, 581-82 (9th Cir. 2016) (citations omitted).

- 8 U.S.C. § 1408 (emphasis added); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("Nationals but not citizens...."); 12 CFR 268.205(a)(7) ("National refers to any individual who meets the requirements described in 8 U.S.C. 1408."); "Certificates of Non Citizen Nationality". Bureau of Consular Affairs. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

- (explaining that lawful permanent residents may lawfully remain outside the United States for up to one year (or even longer) in certain situations).

- Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 341 (1997) ("The plainness or ambiguity of statutory language is determined by reference to the language itself, the specific context in which that language is used, and the broader context of the statute as a whole."); see also Matter of Dougless, 26 I&N Dec. 197, 199 (BIA 2013) ("The [Supreme] Court has also emphasized that the Chevron principle of deference must be applied to an agency’s interpretation of ambiguous statutory provisions, even where a court has previously issued a contrary decision and believes that its construction is the better one, provided that the agency's interpretation is reasonable.").

- Stanton, Ryan (May 11, 2018). "Michigan father of 4 was nearly deported; now he's a U.S. citizen". www.mlive.com. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- Sakuma, Amanda (October 24, 2014). "Lawsuit says ICE attorney forged document to deport immigrant man". MSNBC. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- 18 U.S.C. § 2441 ("War crimes").

- Stevens, Jacqueline (June 2, 2015). "No Apologies, But Feds Pay $350K to Deported American Citizen". LexisNexis. See also "Peter Guzman and Maria Carbajal v. United States, CV08-01327 GHK (SSx)" (PDF). U.S. District Court for the Central District of California (CDCA). www.courtlistener.com. June 7, 2010. p. 3. Retrieved 2018-10-22. (paying $350,000 to plaintiffs for suffering a miscarriage of justice in 2007).

- Ahmadi v. Ashcroft, et al., No. 03-249 (E.D. Pa. Feb. 19, 2003) ("Petitioner in this habeas corpus proceeding, entered the United States on September 30, 1982 as a refugee from his native Afghanistan. Two years later, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the 'INS') adjusted Petitioner's status to that of a lawful permanent resident.... The INS timely appealed the Immigration Judge's decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (the 'BIA').") (Baylson, District Judge); Ahmadi v. Att'y Gen., 659 F. App'x 72 (3d Cir. 2016) (Slip Opinion, pp.2, 4 n.1) (invoking statutorily nullified case law, the court dismissed an obvious illegal deportation case by asserting that it lacks jurisdiction to review an unopposed United States nationality claim under and solely due to ) (non-precedential); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 16-73974 (9th Cir. Apr. 25, 2017) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 17-2672 (2d Cir. Feb. 22, 2018) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); cf. United States v. Wong, 575 U.S. ___, ___, 135 S.Ct. 1625, 1632 (2015) ("In recent years, we have repeatedly held that procedural rules, including time bars, cabin a court's power only if Congress has clearly stated as much. Absent such a clear statement, ... courts should treat the restriction as nonjurisdictional.... And in applying that clear statement rule, we have made plain that most time bars are nonjurisdictional.") (citations, internal quotation marks, and brackets omitted) (emphasis added); see also Bibiano v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 966, 971 (9th Cir. 2016) ("Section 1252(b)(2) is a non-jurisdictional venue statute") (collecting cases) (emphasis added); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (the court clarified "that § 1252(f)(2)'s standard for granting injunctive relief in removal proceedings trumps any contrary provision elsewhere in the law.").

- "Subtitle J—Provisions Relating to the Deportation of Aliens Who Commit Aggravated Felonies, Pub. L. 100-690, 102 Stat. 4469-79, § 7342". U.S. Congress. November 18, 1988. pp. 289–90. Retrieved 2018-09-26.

Section 101(a) (8 U.S.C. 1101(a)) is amended by adding at the end thereof the following new paragraph: '(43) The term 'aggravated felony' means murder, any drug trafficking crime as defined in section 924(c)(2) of title 18, United States Code], or any illicit trafficking in any firearms or destructive devices as defined in section 921 of such title, or any attempt or conspiracy to commit any such act, committed within the United States.'

- Zivkovic v. Holder, 724 F.3d 894, 911 (7th Cir. 2013) ("Because [Petitioner]'s aggravated felony convictions were more than a decade old before the 1988 statute took effect, they cannot be used as a ground for removal...."); Ledezma-Galicia v. Holder, 636 F.3d 1059, 1080 (9th Cir. 2010) ("[Petitioner] is not removable by reason of being an aggravated felon, because 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii) does not apply to convictions, like [Petitioner]'s, that occurred prior to November 18, 1988."); but see Canto v. Holder, 593 F.3d 638, 640-42 (7th Cir. 2010) (good example of absurdity and violation of the U.S. Constitution).

- 8 CFR 1003.2 ("Reopening or reconsideration before the Board of Immigration Appeals"); ("Burden on alien"); (explaining that "a decision that an alien is not eligible for admission to the United States is conclusive unless manifestly contrary to law....").

- See generally Toor v. Lynch, 789 F.3d 1055, 1064-65 (9th Cir. 2015) ("The regulatory departure bar [(8 CFR 1003.2(d))] is invalid irrespective of the manner in which the movant departed the United States, as it conflicts with clear and unambiguous statutory text.") (collecting cases); see also Blandino-Medina v. Holder, 712 F.3d 1338, 1342 (9th Cir. 2013) ("An individual who has already been removed can satisfy the case-or-controversy requirement by raising a direct challenge to the removal order."); United States v. Charleswell, 456 F.3d 347, 351 (3d Cir. 2006) (same); Kamagate v. Ashcroft, 385 F.3d 144, 150 (2d Cir. 2004) (same); Zegarra-Gomez v. INS, 314 F.3d 1124, 1127 (9th Cir. 2003) (holding that because petitioner's inability to return to the United States for twenty years as a result of his removal was "a concrete disadvantage imposed as a matter of law, the fact of his deportation did not render the pending habeas petition moot.").

- Salmoran v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-2683, p.5 n.5 (3d Cir. Nov. 26, 2018) (case involving cancellation of removal after the LPR has been physically removed from the United States on a bogus aggravated felony charge).

- Matter of Cota, 23 I&N Dec. 849, 852 (BIA 2005).

- See generally,

- "Path to U.S. Citizenship". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). January 22, 2013. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- "How to Apply for U.S. Citizenship". www.usa.gov. September 4, 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-14.

- Matter of Navas-Acosta, 23 I&N Dec. 586 (BIA 2003).

- "Destination USA: 75 million international guests visited in 2014". share.america.gov. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- "International Visitation to the United States: A Statistical Summary of U.S. Visitation" (PDF). U.S. Department of Commerce. 2015. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-09-30.

- ("An illegal alien ... is any alien ... who is in the United States unlawfully....").

- ("Benefits and status during period of temporary protected status").

- Edwards v. Sessions, No. 17-87, p.3 (2d Cir. Aug. 24, 2018) ("In removal proceedings involving an LPR, the government bears the burden of proof, which it must meet by adducing clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence that the facts alleged as grounds for deportation are true.") (internal quotation marks omitted) (summary order); accord 8 CFR 1240.46(a); ; Mondaca-Vega v. Lynch, 808 F.3d 413, 429 (9th Cir. 2015) (en banc) ("The burden of proof required for clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence is greater than the burden of proof required for clear and convincing evidence."), cert. denied, 137 S.Ct. 36 (2016); Ward v. Holder, 733 F.3d 601, 604–05 (6th Cir. 2013); United States v. Thompson-Riviere, 561 F.3d 345, 349 (4th Cir. 2009) ("To convict him of this offense, the government bore the burden of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that (inter alia) he is an 'alien,' which means he is 'not a citizen or national of the United States,'" (citations omitted); Francis v. Gonzales, 442 F.3d 131, 138 (2d Cir. 2006); Matter of Pichardo, 21 I&N Dec. 330, 333 (BIA 1996) (en banc); Berenyi v. Immigration Dir., 385 U.S. 630, 636-37 (1967) ("When the Government seeks to strip a person of [United States nationality] already acquired, or deport a resident alien and send him from our shores, it carries the heavy burden of proving its case by 'clear, unequivocal, and convincing evidence.' . . . [T]hat status, once granted, cannot lightly be taken away...." (footnotes omitted)); Woodby v. INS, 385 U.S. 276, 285 (1966); Chaunt v. United States, 364 U.S. 350, 353 (1960).

- ; ("Requirements of naturalization").

- "Justice Department Seeks to Revoke Citizenship of Convicted Felons Who Conspired to Defraud U.S. Export-Import Bank of More Than $24 Million". Office of Public Affairs. U.S. Dept. of Justice (DOJ). May 8, 2018. Retrieved 2018-10-17.

- Matter of S-O-G- & F-D-B-, 27 I&N Dec. 462 (A.G. 2018) ("Immigration judges may dismiss or terminate removal proceedings only under the circumstances expressly identified in the regulations, see 8 CFR 1239.2(c), (f), or where the Department of Homeland Security fails to sustain the charges of removability against a respondent, see 8 CFR 1240.12(c)."); see also Matter of G-N-C-, 22 I&N Dec. 281 (BIA 1998) (en banc).

- Chung, Andrew (April 17, 2018). "Supreme Court restricts deportations of immigrant felons". Reuters. Retrieved 2018-11-02. See also Sessions v. Dimaya, 584 U.S. ___ (2018); Mateo v. Att'y Gen., 870 F.3d 228 (3d Cir. 2017).

- ; see also Matter of G-G-S-, 26 I&N Dec. 339, 347 n.6 (BIA 2014).

- ("Paragraph (1) shall not apply to an alien if the Attorney General determines that— ... (ii) the alien, having been convicted by a final judgment of a particularly serious crime, constitutes a danger to the community of the United States") (emphasis added).

- United States v. Vidal–Mendoza, 705 F.3d 1012, 1013-14 n.2 (9th Cir. 2013) ("Voluntary departure is not available to an alien who has been convicted of an aggravated felony.").

- Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 443 (2009) (Justice Alito dissenting with Justice Thomas).

- United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264-65 n.3 (1997) (internal quotation marks omitted) (emphasis added).

- Mintier, Tom (November 19, 2002). "One-way ticket for convicted Cambodians". CNN. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- Schwartzapfel, Beth (May 14, 2005). "Fighting to Stay". AlterNet. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- Men, Kimseng (April 6, 2018). "Cambodian-Born US Man Deported Back to Country He Doesn't Remember". Voice of America (VoA). Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Montlake, Simon (February 11, 2003). "Cambodians deported home". BBC. Retrieved 2006-10-03.

- "Historical Data: Immigration and Customs Enforcement Removals". TRAC Reports, Inc. 2016. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Sarah, Hoye (September 1, 2011). "Federal deportation review comes too late for some". CNN. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Cambodian Son. Studio Revolt. 2014. Event occurs at 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Raguraman, Anjali (Apr 18, 2016). "Cambodian spoken word artist Kosal Khiev went from prison to poetry". The Strait Times. Retrieved Dec 27, 2018.

- https://www.pbs.org/independentlens/sentencedhome/film.html

- "Rally for Mout and Chally – Front & Champlost – 09.23.10". September 23, 2010. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

External links

- Deported: Forced Family Separation (Part 2 of 5) | NBC Asian America (NBC, March 16, 2017) (video)

- Deported from U.S., Cambodians fight immigration policy (video)

- Torn families of Cambodian refugees deported from US (Charlotte Pert, Al Jazeera, June 26, 2016)

- Judge Keeps His Word to Immigrant Who Kept His (Nina Bernstein, New York Times, February 18, 2010)

- Returnee Integration Support Program

- Sentenced Home, pbs.org

- Clip about KK from Straight Up Refugees Documentary (video)