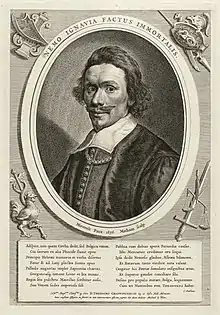

Dirk Graswinckel

Theodorus Johannes "Dirk" Graswinckel[1] (1 October 1600 – 12 October 1666[2]) was a Dutch jurist, a significant writer on the freedom of the seas. He was a controversialist, who also rose to a high legal position (Fiscal of Holland) where he advised Descartes.[3] He was a cousin and pupil of Grotius.[4] He was also a poet and translator of Thomas à Kempis.[5]

Life

He was born in Delft, and studied at the University of Leiden. He joined Grotius in Paris in 1624, and later defended him against Johannes a Felden (John De Felde).

Libertas Veneta (1634) replied to the anonymous anti-Venetian pamphlet Squitinio della liberti veneta (1612). It is in effect also an answer to a work on maritime law by William Welwod.

Maris liberi vindiciae attacked Burgus (Pietro Battista Borgo) writing for Genoese pretensions in the Ligurian Sea,[6][7] but also took on John Selden on the British claim to territorial waters.[8] Selden's Mare Clausum had been published in an English translation in 1652, and he replied the following year with Ioannis Seldeni vindiciae secundum integritatem existimationis suae. In fact Graswinckel had sent Selden a detailed critique in manuscript in 1635.[9]

In 1651 he published a work Placcaten, ordonnantien ende reglementen on the economics of regulation of the grain trade. This came down largely on the side of free trade and the price mechanism.[10] Joseph Schumpeter argued that this was the first clear-cut statement that speculators had a role in the stability of commodity markets.[11]

He died in Mechelen.

Works

- Libertas Veneta (1634)

- De Jure Majestatis (1642)

- Dissertatio de jure praecedentiae inter serenissimam Venetam Rempubl. & sereniss. Sabaudiae ducem (1644)

- Maris liberi vindiciae: adversus P. B. Burgum (1652)

- Stricturae ad censuram Joannis à Felden (1654)

- Nasporinge van het recht van de opperste macht toekomende de Edele Groot Mogende Heeren Staten van Holland en Westvriesland (1667)

References

- Louis Mayeul Chaudon (1810), Dictionnaire universel, historique, critique, et bibliographique, p. 34

- Joseph Michaud, Louis Gabriel Michaud (1816), Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne

Notes

- Dirck or Theodor Graswinckel or Graswinkel, Theodorus Graswinckelius.

- GRASWINCKEL, Dirk (Theodorus) Johannes in Correspondence of Descartes: 1643 Archived 2011-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, pp 263-266.

- Desmon M. Clarke, Descartes: A biography (2006), p. 243.

- http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Diplomacy_and_the_Study_of_International_Relations

- A. W. G. Raath and J. J. Henning, Political Covenantalism, sovereignty and the obligatory nature of law: Ulrich Huber's Discourse on state authority and democratic universalism (PDF), note 57 on p. 8.

- Jan Hendrik Willem Verzijl, Wybo P. Heere, J. P. S. Offerhaus, International Law in Historical Perspective: Nationality and other matters relating to individuals (1968), p. 12.

- Burgus, De dominio Serenissimae Genuensis Reipublicae in mari Ligustico, Roma, Domenico Marciano, 1641.

- R. P. Anand, Law of the Sea: Caracas and Beyond : Developments in International Law (1983), p. 108.

- Richard Tuck, Natural Rights Theories: Their Origin and Development (1981), p. 89.

- Henry W. De Jong, William G. Shepherd, Pioneers of Industrial Organization: How the Economics of Competition and Monopoly Took Shape (2007), pp. 21-2.

- John Barkley Rosser, From Catastrophe to Chaos: A General Theory of Economic Discontinuities (2000), p. 106.