Disability in ancient Rome

Ancient Romans with disabilities were recorded in the personal, medical, and legal writing of the period. While some people with disabilities were sought as slaves, others with disabilities that are now recognized by modern medicine were not considered disabled. Some disabilities were deemed more acceptable than others, either as honorable characteristics or as traits that increased morality. Small, scattered medical references contain the only direct acknowledgments of disability in ancient Rome.

Medical opinion

Soranus of Ephesus (a Methodic doctor who worked in Rome) wrote in his extant treatise on gynaecology that only certain children were worth raising, listing the various tests one could perform on a child to identify disabilities which might render them not worthy. The treatise also states that the physical and mental fitness of a midwife or wet nurse also needed to be assessed by parents.[1]

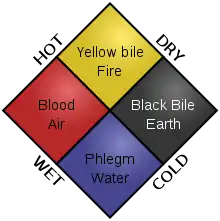

The later Roman physician Galen also mentioned the deficiencies of people with disabilities in his works on anatomy, claiming that both physical and mental impairments resulted from physical imbalances of the four humors.[2] As such, he held to the traditional triad of melancholy, mania, and phrenitis as the three categories of mental disorder.[3]

Romans separated disabilities by their limitations, certain deformities or impairments considered more capable then others. wealth and class also determined the impact a disability had on a Roman citizens daily life.[4]

Roman doctors had a variety of terms to describe different degrees of optical impairment. Aulus Cornelius Celsus in his treatise On Medicine (De Medicina), devoted a chapter to the subject of common eye infections, disease, problems, and their cures.[3]

For women, medical approaches to mental illnesses were considered separate and uniquely different than men's.[3]

Roman laws on disability

The Twelve Tables included a law that said disabled or deformed children should be put to death, usually by stoning. They also stipulated that if a free person or a slave is injured and subsequently disabled by an individual, the injurer has to pay a certain amount of money or is punished by being disfigured in a similar fashion.[5]

In addition, Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote that the city's founder Romulus required children who were born disabled to be exposed on a hillside. Historians think that this was a fairly common practice due to a believed high number of congenital defects due to the prevalence of poor nutrition, incest, and disease.[6] As time passed however, enforcement of this law became less and less common until eventually in the third century, it was reversed by a new law requiring parents to take care of infants who were disabled.[7]

It is also stated that those with physical disabilities like deafness would be given a person to represent them in court if it was required. Roman society valued the act of communication and private interaction, and the law did its best to accommodate those with physical disabilities affecting sight, hearing and speech. The Romans shared an indifference to those with mobility issues and disabilities handicapping their ability to travel. Problems arose with the many legalities in ancient Rome that required face-to-face, physical and private meetings not allowing the substitution of a slave or representative.[8]

In Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Julius Caesar mentions that the Gauls commonly maimed his centurions, usually by blinding them, mentioning that four centurions out of a cohort were blinded. Soldiers disabled in such circumstances were given a stipend by the state once they retired.[9]

In Roman law the blind experienced the least amount of troubles, as there was a higher value placed on speech rather than sight, but were still not given any extreme or special accommodations. Blind people in Rome were seen as capable to provide and care for themselves as any other Roman citizen. One of the few exceptions was will writing, as without the ability to see, multiple witnesses had to be present. Unlike the deaf or those deemed mentally incapable, blind citizens had the option to represent and speak for themselves in court, but were unable to speak for or represent anyone else.

Deaf and mute people experienced some difficulty with Roman law when it came to transactions like buying and selling. Most Roman agreements relied on verbal affirmation for a transaction to be considered complete, hindering deaf and/or mute citizens.[8]

There were chances and times when disabled Roman citizens took higher positions of power within systems like the Senate[8] or other leadership roles, but they had a harder time gaining respect from their peers and those under them.[10]

Emperors such as Nero or Caligula, are said to have used disfigurement or disablement as punishments for legal infractions, as well as personal attacks.[3]

In Roman culture

Blindness or partial blindness was highly regarded in the Roman psyche. Many individuals became famous after losing an eye. Notably, slaves would sometimes enter gladiatorial matches with a patch over a functioning eye, though historians disagree on whether this was in reference to the mythical cyclops or to make the gladiator appear more experienced.[3] It is also known that many mythological figures, as well as known historical individuals, were thought by the Romans to have been blinded in return for favors from their gods. Such gifts varied from foresight to talent in singing. The language of the day also made note of those who were fully blind, caecus, and those who were partially sighted, luscus.[3] Some blind children became beggars.[11]

Physical disabilities affecting sight, hearing and speech made daily life difficult for the Roman citizen, as in Roman culture the act of communication and private interaction was of high importance.[8]

Disabilities from injuries received while in the military were seen as marks of honor as opposed to simple disfigurements, with injuries to the eyes appearing most frequently in both common soldiers and famous personalities such as Hannibal.[3] Many Roman writers, such as Seneca the Younger, would write about the physical failures of prominent Roman civilians who had earned no such honor and whom they wished to lampoon. Roman leaders typically had themselves depicted as physically perfect in statues and coinage.[3] Pliny describes a wealthy but disabled man as being worthy of pity.[12]

During the Augustan period of Rome, Augustus used deformed or disabled slaves as entertainment and display pieces that he invited the public to view. Augustus provided the people a way to view the unique and varying deformities as it interested himself, it is Suetonius that makes sure others are aware that he still thought lowly of them.[13]

Deformed slaves were so popular that Plutarch writes about the different kinds of deformations on display at the Monster Markets. It was recorded that many Roman women kept hunchbacks as pets. Hunchbacks appeared in the court of Caligula. Hunchbacks were popular as displays during symposiums.[13]

Held in a separate area of slave markets, as Plutarch called them, τεράτων ἀγορὰν, or the “market of monsters”.[14] These markets were so popular that the demand for deformed slaves lead to cages (glottokomae) that were used to stunt a person's growth and essentially dwarf them. People were deliberately disfigured, and people were willing to pay more or extra for the deformed slaves.[13]

Individuals with spinal deformities were fairly common in public life, and in fact hunchbacks were in some places considered to be a source of luck for others.[15] Further, they were occasionally known to rise to stations of eminent advisors, such as Nero's advisor Vatinius.

That the god Vulcan was lame yet worked as a smith has led many historians to believe that disabled Romans similarly specialized to accommodate their injuries but were not outcast.[12]

Attitudes towards the disabled

Historians who study the conditions of the ancient world imagine that nearly everyone in society has some form of injury, impairment, or deformity.[16] Moreover, Roman law did its best to accommodate specific handicaps,[8] which would have normalized what we consider disability today.[10]

Depending on one's status, impairments would have more or less impact on their daily life. For example, mobility issues among the elite were less of a problem, since their servants and slaves were tasked to carry them around. Whereas, among the lower and middle class citizens, mobility issues might impede their job prospects.[4]

Yet, deformities and impairments could be seen in a negative light in certain situations. For example, people with extreme deformities and disfigurements were occasionally included in spectacles.[17] In these contexts, it was acceptable to insult and humiliate them, such as mocking their appearance addressing those who have lost an eye as cyclops.[10] Moreover, when someone wanted to attack or demean an opponent, they could interpret their deformities or impairment as a sign of their moral failings or a sign of God's punishment or disfavor.[16]

Disabilities as moral descriptors

In ancient literary texts disabilities are used as defining traits to a character or significant Roman figure. The language used to describe a deformity highlighted either their ugly, or unique looks and character.[13]

Nero and Augustus shared similar deformity in the spotted discoloration of the skin or corpora maculosa (spotted bodies), of the two only Nero's were considered foul and a disfigurement.[13] Augustus's were described as "scattered about his breast and belly in form, order, and number as the stars of the Great Bear in the heavens".[18]

Romans with disabilities

In regards to historical documentation of disabilities in the ancient world, there are few records that provide in-depth details about disabilities.

- Roman dictator Julius Caesar suffered from seizures.[19][20]

- The Roman censor Appius Claudius Crassus received the nickname "Caecus" due to his blindness.

- Gaius Livius Drusus went blind young but became a successful jurist.[21]

- Gaius Gemellus Horigenes (born c. 171 AD- referring to himself as a Roman citizen in 214 AD) is the most well documented individual of the ancient world. The findings of his family's archive gave detailed information about his community and life, lost one eye and developed a cataract in the other.[10] Gaius suffered from a physical disability that was considered less of a limitation by the Romans.

The next few Notable Romans also suffered from some form of physical and/or mental disabilities, some are backed by supportive evidence and others are speculation based on others accounts.

- Quintus Pedius was a deaf painter who is mentioned in Pliny's Natural History.[22]

- Senator Gnaeus Domitius Tullus (84 AD) in his old age and suffering from illness he became crippled and unable to care for himself without the assistance of others. Pliny the Younger writes him as pitiful and living ignorant to the indignity he puts himself through.[10]

- Marcus Sergius (218–201 BC) lost his hand during the second Punic war and is known for being the first to us a prosthetic replacing it with one made of iron and continuing to fight.[10]

- Spurius Carvilius was embarrassed to leave his home because of his disability even with encouragement from his mother to see his situation as a symbol of valor for bring a war veteran.[10]

- Justin II (520–578, ruled Eastern Roman Empire 565–578) was driven mad in his last five years according to John of Ephesus, and spent them locked in the palace on a wheeled throne which was moved by attendants whom he frequently tried to bite. His men would push the chair around the palace at great speed and play organ music among other things in attempts to distract the raving emperor and calm him down.[23]

- Claudius I (10 BC–54 AD, ruled 41–54) was depicted as having speech and physical disorders by Seneca the Younger but it is uncertain whether this was political satire or fact.[24][3]

References

- Soranus, of Ephesus ; Temkin (1991-01-01). Soranus' gynecology.

- Hippocrates, The Writings of Hippocrates and Galen [1846].

- Laes, Christian; Goodey, Chris; Rose, M. Lynn (2013-05-30). Disabilities in Roman Antiquity: Disparate Bodies A Capite ad Calcem. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004251250.

- Rose, Martha L; Goodey, C. F.; Laes, Christian (2013). Disabilities in Roman Antiquity : Disparate Bodies, a Capite Ad Calcem. Leiden: Brill.

- The XII tables. London. 1886. hdl:2027/hvd.32044097726335.

- Avalos, Hector; Melcher, Sarah J.; Schipper, Jeremy (2007-01-01). This Abled Body: Rethinking Disabilities in Biblical Studies. Society of Biblical Lit. ISBN 9781589831865.

- "Disability in Ancient Rome". Rooted in Rights. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Gardner, Jane (1993). Being a Roman Citizen. London: Routledge.

- Sage, Michael M. (2013-01-11). The Republican Roman Army: A Sourcebook. Routledge. ISBN 9781134682881.

- Draycott, Jane (2015). "RECONSTRUCTING THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF DISABILITY IN ANTIQUITY: A CASE STUDY FROM ROMAN EGYPT". Greece&Rome. 62: 189–205.

- Groche, Nora (November 2, 2016). "The Disabled Beggar - A Literature Review" (PDF). International Labour Office. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- "Ancient world". www.newstatesman.com. Retrieved 2016-11-30.

- Trentin T, Lisa (2011). "Deformity in the Roman Imperial Court". Greece & Rome. 58 (2): 198–205. doi:10.1017/S0017383511000143.

- "The Roman Monster-Market". Spectacular Antiquity. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Trentin, Lisa (2015-06-18). The Hunchback in Hellenistic and Roman Art. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781780939117.

- Upson-Saia, Kristi (2011). "Resurrecting Deformity: Augustine on the Scarred, marked, and Deformed Bodies of the Heavenly Realm". Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- "Reaction". Spectacular Antiquity. 2013-03-19. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius; Rolfe, John Carew (2008). Suetonius in two volumes. 1 1. London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-674-99570-3. OCLC 1074381414.

- Bruschi, Fabrizio (2011). "Was Julius Caesar's epilepsy due to neurocysticercosis?". Trends in Parasitology. Cell Press. 27 (9): 373–374. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2011.06.001. PMID 21757405. Retrieved 2 May 2013.

- McLachlan, Richard S. (2010). "Julius Caesar's Late Onset Epilepsy: A Case of Historic Proportions". Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences Inc. 37 (5): 557–561. doi:10.1017/S0317167100010696. PMID 21059498. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Briscoe, John (2019). Valerius Maximus, ›Facta et dicta memorabilia‹, Book 8: Text, Introduction, and Commentary. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 134. ISBN 9783110664331.

- Pliny the Elder (1857). The Natural History of Pliny. 6. H. G. Bohn.

- John of Ephesus, Ecclesiastical History, Part 3, Book 3

- "Emperor Claudius I: the man, his physical impairment, and reactions to it by Keith Armstrong". Retrieved 2016-10-16.