Dispersion relation

In the physical sciences and electrical engineering, dispersion relations describe the effect of dispersion on the properties of waves in a medium. A dispersion relation relates the wavelength or wavenumber of a wave to its frequency. Given the dispersion relation, one can calculate the phase velocity and group velocity of waves in the medium, as a function of frequency. In addition to the geometry-dependent and material-dependent dispersion relations, the overarching Kramers–Kronig relations describe the frequency dependence of wave propagation and attenuation.

Dispersion may be caused either by geometric boundary conditions (waveguides, shallow water) or by interaction of the waves with the transmitting medium. Elementary particles, considered as matter waves, have a nontrivial dispersion relation even in the absence of geometric constraints and other media.

In the presence of dispersion, wave velocity is no longer uniquely defined, giving rise to the distinction of phase velocity and group velocity.

Dispersion

Dispersion occurs when pure plane waves of different wavelengths have different propagation velocities, so that a wave packet of mixed wavelengths tends to spread out in space. The speed of a plane wave, , is a function of the wave's wavelength :

The wave's speed, wavelength, and frequency, f, are related by the identity

The function expresses the dispersion relation of the given medium. Dispersion relations are more commonly expressed in terms of the angular frequency and wavenumber . Rewriting the relation above in these variables gives

where we now view f as a function of k. The use of ω(k) to describe the dispersion relation has become standard because both the phase velocity ω/k and the group velocity dω/dk have convenient representations via this function.

The plane waves being considered can be described by

where

- A is the amplitude of the wave,

- A0 = A(0,0),

- x is a position along the wave's direction of travel, and

- t is the time at which the wave is described.

Plane waves in vacuum

Plane waves in vacuum are the simplest case of wave propagation: no geometric constraint, no interaction with a transmitting medium.

Electromagnetic waves in a vacuum

For electromagnetic waves in vacuum, the angular frequency is proportional to the wavenumber:

This is a linear dispersion relation. In this case, the phase velocity and the group velocity are the same:

they are given by c, the speed of light in vacuum, a frequency-independent constant.

De Broglie dispersion relations

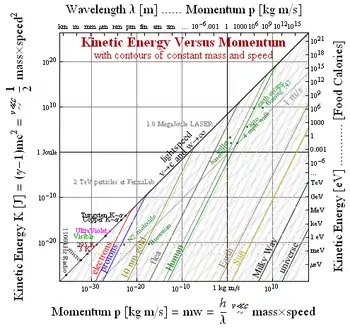

Total energy, momentum, and mass of particles are connected through the relativistic dispersion relation:[1]

which in the ultrarelativistic limit is

and in the nonrelativistic limit is

where is the invariant mass. In the nonrelativistic limit, is a constant, and is the familiar kinetic energy expressed in terms of the momentum .

The transition from ultrarelativistic to nonrelativistic behaviour shows up as a slope change from p to p2 as shown in the log–log dispersion plot of E vs. p.

Elementary particles, atomic nuclei, atoms, and even molecules behave in some contexts as matter waves. According to the de Broglie relations, their kinetic energy E can be expressed as a frequency ω, and their momentum p as a wavenumber k, using the reduced Planck constant ħ:

Accordingly, angular frequency and wavenumber are connected through a dispersion relation, which in the nonrelativistic limit reads

Animation: phase and group velocity of electrons

This animation portrays the de Broglie phase and group velocities (in slow motion) of three free electrons traveling over a field 0.4 ångströms in width. The momentum per unit mass (proper velocity) of the middle electron is lightspeed, so that its group velocity is 0.707 c. The top electron has twice the momentum, while the bottom electron has half. Note that as the momentum increases, the phase velocity decreases down to c, whereas the group velocity increases up to c, until the wave packet and its phase maxima move together near the speed of light, whereas the wavelength continues to decrease without bound. Both transverse and longitudinal coherence widths (packet sizes) of such high energy electrons in the lab may be orders of magnitude larger than the ones shown here.

Frequency versus wavenumber

As mentioned above, when the focus in a medium is on refraction rather than absorption—that is, on the real part of the refractive index—it is common to refer to the functional dependence of angular frequency on wavenumber as the dispersion relation. For particles, this translates to a knowledge of energy as a function of momentum.

Waves and optics

The name "dispersion relation" originally comes from optics. It is possible to make the effective speed of light dependent on wavelength by making light pass through a material which has a non-constant index of refraction, or by using light in a non-uniform medium such as a waveguide. In this case, the waveform will spread over time, such that a narrow pulse will become an extended pulse, i.e., be dispersed. In these materials, is known as the group velocity[2] and corresponds to the speed at which the peak of the pulse propagates, a value different from the phase velocity.[3]

Deep water waves

The dispersion relation for deep water waves is often written as

where g is the acceleration due to gravity. Deep water, in this respect, is commonly denoted as the case where the water depth is larger than half the wavelength.[4] In this case the phase velocity is

and the group velocity is

Waves on a string

For an ideal string, the dispersion relation can be written as

where T is the tension force in the string, and μ is the string's mass per unit length. As for the case of electromagnetic waves in vacuum, ideal strings are thus a non-dispersive medium, i.e. the phase and group velocities are equal and independent (to first order) of vibration frequency.

For a nonideal string, where stiffness is taken into account, the dispersion relation is written as

where is a constant that depends on the string.

Solid state

In the study of solids, the study of the dispersion relation of electrons is of paramount importance. The periodicity of crystals means that many levels of energy are possible for a given momentum and that some energies might not be available at any momentum. The collection of all possible energies and momenta is known as the band structure of a material. Properties of the band structure define whether the material is an insulator, semiconductor or conductor.

Phonons

Phonons are to sound waves in a solid what photons are to light: they are the quanta that carry it. The dispersion relation of phonons is also non-trivial and important, being directly related to the acoustic and thermal properties of a material. For most systems, the phonons can be categorized into two main types: those whose bands become zero at the center of the Brillouin zone are called acoustic phonons, since they correspond to classical sound in the limit of long wavelengths. The others are optical phonons, since they can be excited by electromagnetic radiation.

Electron optics

With high-energy (e.g., 200 keV, 32 fJ) electrons in a transmission electron microscope, the energy dependence of higher-order Laue zone (HOLZ) lines in convergent beam electron diffraction (CBED) patterns allows one, in effect, to directly image cross-sections of a crystal's three-dimensional dispersion surface.[5] This dynamical effect has found application in the precise measurement of lattice parameters, beam energy, and more recently for the electronics industry: lattice strain.

History

Isaac Newton studied refraction in prisms but failed to recognize the material dependence of the dispersion relation, dismissing the work of another researcher whose measurement of a prism's dispersion did not match Newton's own.[6]

Dispersion of waves on water was studied by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1776.[7]

The universality of the Kramers–Kronig relations (1926–27) became apparent with subsequent papers on the dispersion relation's connection to causality in the scattering theory of all types of waves and particles.[8]

See also

References

- Taylor (2005). Classical Mechanics. University Science Books. p. 652. ISBN 1-891389-22-X.

- F. A. Jenkins and H. E. White (1957). Fundamentals of optics. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 223. ISBN 0-07-032330-5.

- R. A. Serway, C. J. Moses and C. A. Moyer (1989). Modern Physics. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 118. ISBN 0-534-49340-8.

- R. G. Dean and R. A. Dalrymple (1991). Water wave mechanics for engineers and scientists. Advanced Series on Ocean Engineering. 2. World Scientific, Singapore. ISBN 978-981-02-0420-4. See page 64–66.

- P. M. Jones, G. M. Rackham and J. W. Steeds (1977). "Higher order Laue zone effects in electron diffraction and their use in lattice parameter determination". Proceedings of the Royal Society. A 354 (1677): 197. Bibcode:1977RSPSA.354..197J. doi:10.1098/rspa.1977.0064. S2CID 98158162.

- Westfall, Richard S. (1983). Never at Rest: A Biography of Isaac Newton (illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University. p. 276. ISBN 9780521274357.

- A. D. D. Craik (2004). "The origins of water wave theory". Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics. 36: 1–28. Bibcode:2004AnRFM..36....1C. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.36.050802.122118.

- John S. Toll (1956). "Causality and the dispersion relation: Logical foundations". Phys. Rev. 104 (6): 1760–1770. Bibcode:1956PhRv..104.1760T. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.104.1760.

External links

- Poster on CBED simulations to help visualize dispersion surfaces, by Andrey Chuvilin and Ute Kaiser

- Angular frequency calculator