Djerba

Djerba (/ˈdʒɜːrbə, ˈdʒɛərbə/; Arabic: جربة, romanized: Jirba IPA: [ˈʒɪrbæ] (![]() listen)), Italian: Meninge or Girba, also transliterated as Jerba[1] or Jarbah,[2] is, at 514 square kilometers (198 sq mi), is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa, located in the Gulf of Gabès,[1] off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 at the 2004 Census which rose to 163,726 at the 2014 Census. Citing the long and unique Jewish minority's history Djerba has had in the past, Tunisia has sought UNESCO World Heritage status protections for the island.[3]

listen)), Italian: Meninge or Girba, also transliterated as Jerba[1] or Jarbah,[2] is, at 514 square kilometers (198 sq mi), is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa, located in the Gulf of Gabès,[1] off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 at the 2004 Census which rose to 163,726 at the 2014 Census. Citing the long and unique Jewish minority's history Djerba has had in the past, Tunisia has sought UNESCO World Heritage status protections for the island.[3]

| Native name: | |

|---|---|

| |

Djerba | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Gulf of Gabès |

| Archipelago | Mediterranean Sea |

| Area | 514 km2 (198 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

| Largest settlement | Houmt Souk (pop. 75,904) |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Djerbian Jerbi |

| Population | 163,726 (2014 Census) |

| Pop. density | 309/km2 (800/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Tunisians (Berbers, Arabs, Jews and Black African) |

History

Legend has it that Djerba was the island of the lotus-eaters[1][4] where Odysseus was stranded on his voyage through the Mediterranean sea. The tradition of the Jewish minority of Djerba says in the year 586 BC, some of the Israelite temple priests who were able to escape the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple there, settled in Djerba; an unusually high percentage of Jews on the island to this day maintain family status of the priestly caste, and a genetic link has been confirmed by DNA testing.

The island, was called Meninx (Ancient Greek: Μῆνιγξ)[5][6][7] until the third century A.D. Strabo writes that there was an altar of the Odysseus.[8]

The island had three principal towns. One of these, whose modern name is Būrgū, is found near Midoun in the center of the island. Another city, on the southeast coast of the island at Meninx, was a major producer of priceless murex dye, and is cited by Pliny the Elder as second only to Tyre in this regard. A third important town was the ancient Haribus. The island was densely inhabited in the Roman and Byzantine periods, and probably imported much of the grain consumed by its inhabitants. The island appears in the 13th century (with possible 4th century origins) Peutinger Map.

During the Middle Ages, Djerba was occupied by Ibadi Muslims, who claimed it as their own. The Christians of Sicily and Aragon disputed this claim with the Ibadites. Remains from this period include numerous small mosques dating from as early as the twelfth century, as well as two substantial forts.

The island was controlled twice by the Norman Kingdom of Sicily: in *1135–1158 and in *1284–1333. During the second of these periods it was organised as a feudal lordship, with the following Lords of Jerba: 1284–1305: Roger I

1305–1307, and 1307–1310: Roger II (twice)

1310: Charles

1310: Francis-Roger III.

There were also royal governors, whose times in power partially overlapped with those of the Lords: c. 1305–1308: Simon de Montolieu

1308–1315: Ramon Muntaner.

In 1503, Barbary pirate Oruç Reis and his brother Hayreddin Barbarossa took control of the island and turned it into their main base in the western Mediterranean, thus bringing it under Ottoman control. Spain launched a disastrous attempt to capture it in November 1510.

In 1513, after three years in exile in Rome, the Fregosi family returned to Genoa, Ottaviano was elected Doge, and his brother, Archbishop Federigo Fregoso (later cardinal), having become his chief educator, was placed at the head of the army, and defended the republic against internal dangers (revolts of the Adorni and the Fieschi) and external dangers, notably suppression of the Barbary piracy: Cortogoli, a corsair from Tunis, blockaded the coast with a squadron, and within a few days had captured eighteen merchantmen; being given the command of the Genoese fleet, in which Andrea Doria was serving, Federigo surprised Cortogoli before Bizerta. Soon after, he carried out an invasion and occupation of the island and returned to Genoa with great booty.

Spanish forces returned to Djerba in 1520, and this time were successful in capturing the island. It was twice occupied by Spain, from 1521 to 1524 and from 1551 to 1560.

On 14 May 1560, the Ottoman fleet, under the command of Piali Pasha and Dragut, severely defeated the "Holy League" of Philip II of Spain at the Battle of Djerba. From that time until 1881, Djerba belonged to the Ottoman regency of Tunis.

Subsequently, it came under the French colonial protectorate, which became the modern republic of Tunisia.

An archaeological field survey of Djerba carried out between 1995 and 2000 under the auspices of the University of Pennsylvania, the American Academy in Rome and the Tunisian Institut National du Patrimoine, revealed over 400 archaeological sites, including many Punic and Roman villas[9] and an Amphitheatre.

Jewish history

According to their oral history, the Jewish minority has dwelled on the island continuously for more than 2,500 years.[10][11] The first physical evidence that historians know of come from the 11th century found in Cairo Geniza.[12]

This community is unique in the Jewish diaspora for its unusually high percentage of Kohanim (Hebrew; the Jewish priestly caste), direct patrilineal descendants of Aaron the first high priest from Mosaic times.[12] Local tradition tells that when Nebuchadnezzar II leveled Solomon's temple and lay waste to Judah and the city of Jerusalem in the year 586 BC, among the refugees who avoided slavery were the Kohanim who settled in Djerba.[13]

A key point in this oral history has been backed up by genetic tests for Cohen modal haplotype showing that the vast majority of male Jews on Djerba claiming the family status of Cohen had a common ancient male ancestor which matches that of nearly all of both historically European and Middle Eastern Jewish males with a family history of patrilineal membership in the Jewish priestly caste.[14]

Thus, the island has been known by many Jews as the island of the Kohanim. During the destruction of the temple, the Kohanim, who were serving the temple at the time of destruction escaped from Jerusalem and found themselves on the island of Djerba.[12] The legend claims the Kohanim carried the door and some stones from the Temple in Jerusalem which they then incorporated into the "marvelous synagogue", also known as Ghriba, which still stands in Djerba.[12]

The Jewish community differs from others in Djerba in their dress, personal names, and accents. The Jewish rabbinate of Djerba have established an eruv, which establishes the communal area in the city in which Jews can freely carry objects between their homes and community buildings on Shabbat.[15] Some traditions that are distinctive of the Jewish Djerba community is the kiddush prayer said on the eve of Passover and a few prophetic passages on certain Shabbats of the year.[12]

One of the community's synagogues, the El Ghriba synagogue, has been in continuous use for over 2,000 years.[16] The Jews were settled in two main communities: the Hara Kabira ("the big quarter") and the Hara Saghira ("the small quarter"). The Hara Saghira identified itself with Israel, while the Hara Kabira identified with Spain and Morocco.[17]

The next influx of Jewish people to the Island of Djerba was during the Spanish Inquisition, when the Iberian Jewish population was no longer welcome and were forced to leave.[18] The Jewish population hit its peak during the time that Tunisia was fighting for independence from France 1881–1956.[18] In 1940, there were approximately 100,000 Jewish-Tunisians or 15% of the entire population of Tunisia.[18]

In the aftermath of World War II, the Jewish population on the island declined significantly due to emigration to Israel and France. As of 2011, the Jewish permanent resident community on the island numbered about 1,000,[11][19] but many return annually on pilgrimage. However, once the State of Israel was established, and political unrest in the Middle East and North Africa was building up many Jewish people left Tunisia.[18] Although the Jewish community of Tunisia was on the decline, the Jewish community of Hara Kebira witnessed an increase of population due to its traditional character.[18] The community on Djerba remains one of the last remaining fully intact Jewish communities in an Arab majority country after most were abandoned in the face of anti-Israel and antisemitic pressure and pogroms. The most traditionally observant Jewish community is growing because of large natural families despite emigration and a new Orthodox Jewish school for girls has recently been inaugurated on the Island to serve alongside the two boy's yeshiva schools. According to the Wall Street Journal "Relations between Jews and Muslims are complex—proper and respectful, though not especially close. Jewish men work alongside Arab merchants in the souk, for example, and enjoy amicable ties with Muslim customers."[20]

The historical conflicts between Muslims and Jewish people have been largely absent in Djerba. This is reportedly attributed to the fact that all the people of the island were at some point Jewish and therefore share similar practices in their ways of life.[12]

Some of these Jewish practices that can be seen in Muslim households in Djerba are the lighting of candles on Friday night, and the suspending of matzot on the ceiling from one spring to the next.[12] The Jewish and Muslim communities have coexisted peacefully in Djerba despite political unrest regarding the Israeli- Palestinian conflict. The people of Djerba say that the two communities simply pray in different places, but are still able to converse.[21] A Jewish leader once stated "We live together, We visit our friends on their religious holidays. We work together. Muslims buy meat from our butchers. When we are forbidden to work or cook on the Shabbat, we buy bread and kosher food cooking by Muslims. Our children play together".[21]

On 11 April 2002, Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for a truck bomb attack close to the famous synagogue, killing 21 people (14 German tourists, 5 Tunisians and 2 French nationals).[22]

Since the "Arab Spring", the Tunisian government has extended their protection and encouraged Jewish life on the island of Djerba.[13] Citing the long and unique Jewish history on Djerba, Tunisia has sought UNESCO World Heritage status for the island.[3] There are currently 14 synagogues, 2 yeshivot, and 3 kosher eateries.[13]

A Jewish school on the island was firebombed during the national protests held in 2018, while security forces in Djerba were reduced, being preoccupied with protection efforts elsewhere.[23] This attack was among many other uprisings that were occurring throughout Tunisia at the time.[23]

Ecclesiastical history

The city Girba in the Roman province of Tripolitania (mostly in modern Libya), which gave its name to the island, was important enough to become a suffragan bishop of its capital's archbishopric. Known Bishops of antiquity include:

- Proculus (Maximus Bishop fl.393)

- Quodvultdeus (Catholic Bishop fl.401–411) attending Council of Carthage (411)

- Euasius (Donatist Bishop fl.411) rival at Council of Carthage

- Urbanus (Catholic bishop fl.445–454)

- Faustinus (Catholic bishop fl. 484), exiled by King Huneric of the Vandal Kingdom

- Vincentius (Catholic bishop fl. 523–525)

The 1909 Catholic Encyclopedia lists only two: "At least two bishops of Girba are known, Monnulus and Vincent, who assisted at the Councils, of Carthage in 255 and 525".[24]

Titular see of Girba

The Ancient diocese of Girba was nominally restored in 1895 as a Latin titular bishopric of the lowest (episcopal) rank.

It has had the following incumbents :

- Victor Roelens, White Fathers (M. Afr.) (1895.03.30 – 1947.08.05)

- Carlos Eduardo de Sabóia Bandeira Melo, Order of Friars Minor (1947.12.13 – 1958.04.11)

- Henryk Strakowski (1958.05.03 – 1965.05.06)

- Mariano Gaviola y Garcés (1967.05.31 – 1981.04.13) as former bishop of Cabanatuan, Philippines (1963.03.08 – 1967.05.31), Military Vicar of the Philippines (1974.03.02 – 1981.04.13), President of Federation of Asian Bishops' Conferences (1977–1984), Metropolitan Archbishop of Lipa, Philippines (1981.04.13 – 1992.12.30)

- Jacques David (1981.07.27 – 1985.02.21)

- Paul Kim Ok-kyun (Korean: 김옥균 바오로) (1985.03.09 – 2010.03.01)

- Victor Emilio Masalles Pere, auxiliary bishop of the Santo Domingo (2010.05.08 – ?)

- James T. Schuerman, auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Milwaukee (2017.01.23 – ...)

Administration and population

The island comprises three of the delegations within the Tunisian Département of Médenine. Named after the three towns which form their administrative centers, these delegations, with their areas and their 2004 and 2014 Census populations, are:

| Name | Arabic name | Area in km2 | Population Census 2004 | Population Census 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djerba Houmet Souk | جربة حومة السوق | 163 | 64,919 | 75,904 |

| Djerba Midoun | جربة ميدون | 189 | 50,459 | 63,528 |

| Djerba Ajim | جربة أجيم | 159 | 24,166 | 24,294 |

Berbers

Jerba Berber, a Berber language, called chelha by its speakers, is spoken in some villages, including Iguellalen, Ajim, Sedriane, Sedouikech, Azdyuch, Mahboubine and Ouirsighen.

Geography

Djerba is an island in the Gulf of Gabès in the Mediterranean Sea. Its largest city is Houmt Souk on the northern coast of the island, with a population of around 65,000.

Djerba has hot dry summers and mild winters and has fertile soil. However, until the introduction of the current levels of advanced irrigation and piped water supplies, the month of October tended to supply approximately 25% of its total annual rainfall on the island (see table below). Summer daytime temperatures regularly reach very high levels, making early human habitation less favoured than the north of the country.

Climate

| Climate data for Djerba (1981–2010, extremes 1898–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

35.2 (95.4) |

35.0 (95.0) |

38.6 (101.5) |

43.7 (110.7) |

46.0 (114.8) |

45.2 (113.4) |

46.3 (115.3) |

42.8 (109.0) |

40.0 (104.0) |

33.5 (92.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

46.3 (115.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

26.6 (79.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.5 (92.3) |

30.9 (87.6) |

27.6 (81.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

17.8 (64.0) |

25.0 (76.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.8 (60.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.5 (58.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.3 (75.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 27.4 (1.08) |

14.3 (0.56) |

15.9 (0.63) |

11.8 (0.46) |

5.1 (0.20) |

1.4 (0.06) |

0.3 (0.01) |

1.3 (0.05) |

20.3 (0.80) |

36.2 (1.43) |

27.2 (1.07) |

41.3 (1.63) |

202.5 (7.98) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 24.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 67 | 66 | 66 | 65 | 66 | 63 | 65 | 69 | 68 | 67 | 70 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 207.7 | 207.2 | 244.9 | 264.0 | 313.1 | 321.0 | 375.1 | 350.3 | 276.0 | 248.0 | 213.0 | 204.6 | 3,224.9 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.7 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 8.8 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 12.1 | 11.3 | 9.2 | 8.0 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 8.8 |

| Source 1: Institut National de la Météorologie (precipitation days/humidity/sun 1961–1990)[25][26][27][note 1] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity and sun 1961–1990),[29] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[30] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Djerba | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 16.0 (61.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.0 (61.0) |

17.0 (63.0) |

19.0 (66.0) |

22.0 (72.0) |

26.0 (79.0) |

28.0 (82.0) |

27.0 (81.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

22.0 (72.0) |

18.0 (64.0) |

20.9 (69.8) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6.8 |

| Source #1: Weather2Travel (sea temperature) [31] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weather Atlas [32] | |||||||||||||

Migratory bird sanctuary

Djerba Bin El Ouedian is a wetland and habitat for migratory birds. It is located at 33 ° 40 'N, 10 ° 55 'E. On 7 November 2007 the wetland was included on the list of Ramsar sites under the Ramsar Convention, due to its importance as a bird refuge.[33]

Tourism

Most tourism is focused on the largest city, Houmt Souk, where the Borj El Kebir castle is located.[34]

Most of the hotels and beaches are part of Midoun city.[35]

The commune and port of Ajim in the southwest corner of the island and its surrounding areas were used as filming locations for Star Wars. Tourists can visit buildings featured in the original movie, including Obi-Wan Kenobi's house and the Mos Eisley cantina.[36][37]

Gallery

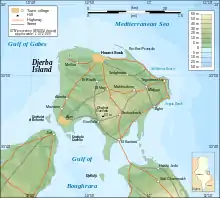

Djerba topographic map.

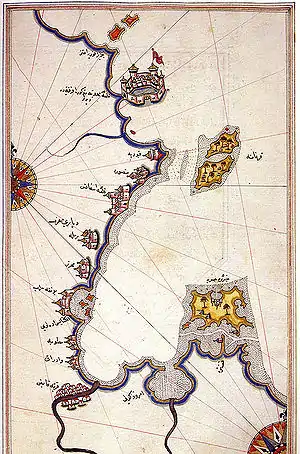

Djerba topographic map. Historic map of Djerba by Piri Reis.

Historic map of Djerba by Piri Reis. Sunset on Djerba.

Sunset on Djerba. Coffeehouse.

Coffeehouse. Bassi Mosque.

Bassi Mosque. Saint Joseph Catholic Church.

Saint Joseph Catholic Church. Street art in Erriadh (Djerbahood)

Street art in Erriadh (Djerbahood)

See also

- European enclaves in North Africa before 1830

- Borj El Kebir

- Menachem Mazuz, former Israeli Attorney General, and, as to 2020, judge in Israel's Supreme Court, born on this island

- Yael Shelbia, Israeli model, descendant of Djerba inhabitants

- Djerba–Zarzis International Airport

Notes

- The Station ID for Djerba is 57070211.[28]

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 322.

- ^ Transliteration from http://www.uconv.com/ar.htm

- Center, UNESCO World Heritage. "Regional Workshop on the World Heritage Nomination Process". UNESCO World Heritage Center. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Polybius; Strabo 1.2.17.

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §M451.1

- Polybius, Histories, §1.39.2

- Strabo, Geography, §2.5.20

- Strabo, Geography, §17.3.17

- E. Fentress, A. Drine and R. Holod, eds. An Island in Time: Jerba Studies vol 1. The Punic and Roman Periods. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary series 71,2009.

- Teich, Shmuel (1982). The Rishonim. Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications. ISBN 978-0-89906-452-9.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Tunisia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- Udovitch, Abraham L.; Valensi, Lucette (1984). The Last Arab Jews: The Communities of Jerba, Tunisia. London, England: Harwood Academic Publishers. pp. 8–11, 24–25. ISBN 978-3-7186-0135-6.

- "WATCH: Candle lighting in Djerba – a Jewish community to admire – Diaspora – Jerusalem Post". jpost.com. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- "Tunisia's Diverse Djerba Island and Its Annual Jewish Pilgrimage". 2 June 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Schroeter, Daniel (1985). "Review of The Last Arab Jews: The Communities of Jerba, Tunisia, (Social Orders 1.)". Middle East Studies Association Bulletin. 19 (1): 63–64. doi:10.1017/S0026318400014905. JSTOR 23057816.

- "Tunisian Cleric Says Jews are Apes". Israel National News. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Spector, Shmuel; Wigoder, Geoffrey (2001). The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust: A-J. New York: NYU Press. p. 312. ISBN 978-0-8147-9376-3.

- Widman, Miriam (19 December 1994). "Behind The Headlines: Amid Sea of Muslim Neighbors, Tunisia Jews Observe Traditions". Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

- Ettinger, Yair (17 January 2011). "Sociologist Claude Sitbon, do the Jews of Tunisia have reason to be afraid?". Haaretz. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- Lagnado, Lucette (13 February 2015). "Tunisian Jewish Enclave Weathers Revolt, Terror; Can It Survive Girls' Education?". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 December 2018 – via www.wsj.com.

- Hanley, Delinda C. (December 2003). "Tunisian Jews Enjoy Religious Tolerance and Peace In Djerba". The Washington Report on Middle Eastern Affairs. 22 (10). pp. 46–49.

- Tunisian bomb attack trial opens, BBC.co.UK; accessed 28 July 2020.

- "Tunisian Jewish school attacked as anti-government protests rage elsewhere". Reuters. 11 January 2018.

- Vailhé, S. (1909). "Girba". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- "Les normales climatiques en Tunisie entre 1981 2010" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Données normales climatiques 1961–1990" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Les extrêmes climatiques en Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Réseau des stations météorologiques synoptiques de la Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Jerba Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Station Djerba" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- "Djerba Climate and Weather Averages, Tunisia". Weather2Travel. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- "Djerba, Tunisia – Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "Tunisia – Ramsar". www.ramsar.org. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Éternelle Djerba, Tunis, Association de sauvegarde de l'île de Djerba et Société tunisienne des arts graphiques, 1998, p. 21

- Elusia. "Z – ZONE TOURISTIQUE". Djerba, un abécédaire (in French). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- The Star Wars Traveler by Gus Lopez and Pamela Gren.

- Loms Galactic Tours by Loms

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Djerba. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Djerba. |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Girba". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Girba". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.