Door-to-balloon

Door-to-balloon is a time measurement in emergency cardiac care (ECC), specifically in the treatment of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (or STEMI). The interval starts with the patient's arrival in the emergency department, and ends when a catheter guidewire crosses the culprit lesion in the cardiac cath lab. Because of the adage that "time is muscle", meaning that delays in treating a myocardial infarction increase the likelihood and amount of cardiac muscle damage due to localised hypoxia,[1][2][3][4] ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a door-to-balloon interval of no more than 90 minutes.[5] As of 2006 in the United States, fewer than half of STEMI patients received reperfusion with primary percutaneous coronary intervention within the guideline-recommended timeframe.[6] It has become a core quality measure for the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (TJC).[7][8][9]

Improving door-to-balloon times

Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative

The benefit of prompt, expertly performed primary percutaneous coronary intervention over thrombolytic therapy for acute ST elevation myocardial infarction is now well established.[10] Few hospitals can provide PCI within the 90 minute interval,[11] which prompted the American College of Cardiology (ACC) to launch a national Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative in November 2006. The D2B Alliance seeks to "take the extraordinary performance of a few hospitals and make it the ordinary performance of every hospital."[12] Over 800 hospitals have joined the D2B Alliance as of March 16, 2007.[13]

The D2B Alliance advocates six key evidence-based strategies and one optional strategy to help reduce door-to-balloon times:[12][14]

- ED physician activates the cath lab

- Single-call activation system activates the cath lab

- Cath lab team is available within 20–30 minutes

- Prompt data feedback

- Senior management commitment

- Team based approach

- (Optional) Prehospital 12 lead ECG activates the cath lab

Mission: Lifeline

On May 30, 2007, the American Heart Association launched 'Mission: Lifeline', a "community-based initiative aimed at quickly activating the appropriate chain of events critical to opening a blocked artery to the heart that is causing a heart attack."[15] It is seen as complementary to the ACC's D2B Initiative.[16] The program will concentrate on patient education to make the public more aware of the signs of a heart attack and the importance of calling 9-1-1 for emergency medical services (EMS) for transport to the hospital.[15] In addition, the program will attempt to improve the diagnosis of STEMI patients by EMS personnel.[15] According to Alice Jacobs, MD, who led the work group that addressed STEMI systems,[17] when patients arrive at non-PCI hospitals they will stay on the EMS stretcher with paramedics in attendance while a determination is made as to whether or not the patient will be transferred.[17] For walk-in STEMI patients at non-PCI hospitals, EMS calls to transfer the patient to a PCI hospital should be handled with the same urgency as a 9-1-1 call.[17]

EMS-to-balloon (E2B)

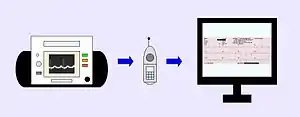

Although incorporating a prehospital 12 lead ECG into critical pathways for STEMI patients is listed as an optional strategy by the D2B Alliance, the fastest median door-to-balloon times have been achieved by hospitals with paramedics who perform 12 lead ECGs in the field.[18] EMS can play a key role in reducing the first-medical-contact-to-balloon time, sometimes referred to as EMS-to-balloon (E2B) time,[19] by performing a 12 lead ECG in the field and using this information to triage the patient to the most appropriate medical facility.[20][21][22][23]

Depending on how the prehospital 12 lead ECG program is structured, the 12 lead ECG can be transmitted to the receiving hospital for physician interpretation, interpreted on-site by appropriately trained paramedics, or interpreted on-site by paramedics with the help of computerized interpretive algorithms.[24] Some EMS systems utilize a combination of all three methods.[19] Prior notification of an inbound STEMI patient enables time saving decisions to be made prior to the patient's arrival. This may include a "cardiac alert" or "STEMI alert" that calls in off duty personnel in areas where the cardiac cath lab is not staffed 24 hours a day.[19] The 30-30-30 rule takes the goal of achieving a 90-minute door-to-balloon time and divides it into three equal time segments. Each STEMI care provider (EMS, the emergency department, and the cardiac cath lab) has 30 minutes to complete its assigned tasks and seamlessly "hand off" the STEMI patient to the next provider.[19] In some locations, the emergency department may be bypassed altogether.[25]

Common themes in hospitals achieving rapid door-to-balloon times

Bradley et al. (Circulation 2006) performed a qualitative analysis of 11 hospitals in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction that had median door-to-balloon times = or < 90 minutes. They identified 8 themes that were present in all 11 hospitals:[6]

- An explicit goal of reducing door-to-balloon times

- Visible support of senior management

- Innovative, standardized protocols

- Flexibility in implementing standardized protocols

- Uncompromising individual clinical leaders

- Collaborative interdisciplinary teams

- Data feedback to monitor progress and identify problems or successes

- Organizational culture that fostered persistence despite challenges and setbacks

Criteria for an ideal primary PCI center

Granger et al. (Circulation 2007) identified the following criteria of an ideal primary PCI center.[24]

Institutional resources

- Primary PCI is the routine treatment for eligible STEMI patients 24 hours a day, 7 days a week

- Primary PCI is performed as soon as possible

- Institution is capable of providing supportive care to STEMI patients and handling complications

- Written commitment by hospital administration to support the program

- Identifies physician director for PCI program

- Creates multidisciplinary group that includes input from all relevant stakeholders, including cardiology, emergency medicine, nursing, and EMS

- Institution designs and implements a continuing education program

- For institution without on-site surgical backup, there is a written agreement with tertiary institution and EMS to provide for rapid transfer of STEMI patients when needed

Physician resources

- Interventional cardiologists meet ACC/AHA criteria for competence

- Interventional cardiologists participate in, and are responsive to formal on-call schedule

Program requirements

- Minimum of 36 primary PCI procedures and 400 total PCI procedures annually

- Program is described in a "manual of operations" that is compliant with ACC/AHA guidelines

- Mechanisms for monitoring program performance and ongoing quality improvement activities

Other features of ideal system

- Robust data collection and feedback including door-to-balloon time, first door-to-balloon time (for transferred patients), and the proportion of eligible patients receiving some form of reperfusion therapy

- Earliest possible activation of the cardiac cath lab, based on prehospital ECG whenever possible, and direct referral to PCI-hospital based on field diagnosis of STEMI

- Standardized ED protocols for STEMI management

- Single phone call activation of cath lab that does not depend on cardiologist interpretation of ECG

Gaps and barriers to timely access to primary PCI

Granger et al. (Circulation 2007) identified the following barriers to timely access to primary PCI.[24]

- Busy PCI hospitals may have to divert patients

- Significant delays in ED diagnosis of STEMI may occur, particularly when patient does not arrive by EMS

- Manpower and financial considerations may prevent smaller PCI programs from providing primary PCI for STEMI 24 hours a day

- Reimbursement for optimal coordination of STEMI patients needs to be realigned to reflect performance

- In most PCI centers, cath lab staff is off-site during off hours, requiring a mandate that staff report with 20–30 minutes of cath lab activation

References

- Soon CY, Chan WX, Tan HC (2007). "The impact of time-to-balloon on outcomes in patients undergoing modern primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction". Singapore Medical Journal. 48 (2): 131–6. PMID 17304392.

- Arntz HR, Bossaert L, Filippatos GS (2005). "European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 5. Initial management of acute coronary syndromes". Resuscitation. 67 Suppl 1: S87–96. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.003. PMID 16321718.

- De Luca G, van't Hof AW, de Boer MJ, et al. (2004). "Time-to-treatment significantly affects the extent of ST-segment resolution and myocardial blush in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty". Eur. Heart J. 25 (12): 1009–13. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.021. PMID 15191770.

- Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. (2000). "Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction". JAMA. 283 (22): 2941–7. doi:10.1001/jama.283.22.2941. PMID 10865271.

- ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Archived June 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:671-719

- Bradley EH, Curry LA, Webster TR, et al. (2006). "Achieving rapid door-to-balloon times: how top hospitals improve complex clinical systems". Circulation. 113 (8): 1079–85. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590133. PMID 16490818.

- National Hospital Quality Measures/The Joint Commission Core Measures Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, Retrieved on June 30, 2007.

- Larson DM, Sharkey SW, Unger BT, Henry TD (2005). "Implementation of acute myocardial infarction guidelines in community hospitals". Academic Emergency Medicine. 12 (6): 522–7. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.008. PMID 15930403.

- Williams SC, Schmaltz SP, Morton DJ, Koss RG, Loeb JM (2005). "Quality of care in U.S. hospitals as reflected by standardized measures, 2002-2004". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (3): 255–64. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa043778. PMID 16034011.

- Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL (2003). "Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials". Lancet. 361 (9351): 13–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. PMID 12517460.

- Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. (November 2006). "Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (22): 2308–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa063117. PMID 17101617.

- John Brush, MD, "The D2B Alliance for Quality," Archived 2007-08-09 at the Wayback Machine STEMI Systems Issue Two, May 2007. Accessed July 2, 2007.

- "D2B: An Alliance for Quality". American College of Cardiology. 2006. Archived from the original on February 12, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- "D2B Strategies Checklist". American College of Cardiology. 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- "Mission: Lifeline - a new plan to decrease deaths from major heart blockages," American Heart Association, May 31, 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- ACC Targets STEMI Times with Emergency CV Care 2007 Archived July 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Accessed July 3, 2007.

- Michael O'Riordan, "AHA Announces Mission: Lifeline, a New Initiative to Improve Systems of Care for STEMI Patients," Heartwire (a professional news service of WebMD), May 31, 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- Bradley EH, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, et al. (2005). "Achieving door-to-balloon times that meet quality guidelines: how do successful hospitals do it?". J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 46 (7): 1236–41. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.009. PMID 16198837.

- Rokos I. and Bouthillet T., "The emergency medical systems-to-balloon (E2B) challenge: building on the foundations of the D2B Alliance," Archived 2007-08-09 at the Wayback Machine STEMI Systems, Issue Two, May 2007. Accessed June 16, 2007.

- Rokos IC, Larson DM, Henry TD, et al. (2006). "Rationale for establishing regional ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks". Am. Heart J. 152 (4): 661–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.001. PMID 16996830.

- Moyer Feldman, Levine; et al. (2004). "Implications of the Mechanical (PCI) vs Thrombolytic Controversy for ST Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction on the Organization of Emergency Medical Services: The Boston EMS Experience". Crit Path Cardiol. 3 (2): 53–61. doi:10.1097/01.hpc.0000128714.35330.6d. PMID 18340140.

- Terkelsen Lassen, Norgaard; et al. (2005). "Reduction of treatment delay in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: impact of pre-hospital diagnosis and direct referral to primary percutanous coronary intervention". Eur Heart J. 26 (8): 770–7. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi100. PMID 15684279.

- Henry Atkins, Cunningham; et al. (2006). "ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Recommendations on Triage of Patients to Heart Attack Centers - Is it Time for a National Policy for the Treatment of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction?". J Am Coll Cardiol. 47 (7): 1339–1345. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.101. PMID 16580518.

- Granger CB, Henry TD, Bates WE, Cercek B, Weaver WD, Williams DO (2007). "Development of Systems of Care for ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients. The Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction-Receiving) Hospital Perspective". Circulation. 116 (2): e55–9. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.184049. PMID 17538039.

- David Jaslow, MD, "Out-of-Hospital STEMI Alert - If Time is Muscle, What's Taking So Long? EMS Responder, March 2007. Accessed July 3, 2007.

External links

- American College of Cardiology (ACC) Door to Balloon (D2B) Initiative

- Q&A: Improving door-to-balloon time for acute MI - American College of Physicians

- Reducing Door to Balloon Time for Acute Myocardial Infarction in a Tertiary Emergency Department - A report by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement

- Regional PCI for STEMI resource center - Evidence based resource center for the development of regional PCI networks for acute STEMI

- STEMI Systems Quarterly newsletter for STEMI care professionals

Media coverage

- "Hospitals too slow on heart attacks," USA Today, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals Join to Speed Care After Heart Attacks," The New York Times, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Saving Time, Saving Lives," ABC News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Heart Attack Care In Critical Condition," CBS News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals Seek to Speed Up Emergency Heart Attack Care," Fox News, November 13, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.

- "Hospitals race to improve heart attack care," MSNBC.com, November 14, 2006. Accessed July 3, 2007.