Douglas Arthur Teed

Douglas Arthur Teed (21 February 1860 – 23 May 1929) was an American painter. He was the only son of the founder of Estero, Florida and self-proclaimed messiah, Dr. Cyrus Teed. Teed was noted as an experimental artist, who explored virtually all styles associated with Aesthetic art.

Douglas Arthur Teed | |

|---|---|

Douglas Arthur Teed | |

| Born | 21 February 1860 New Hartford, New York |

| Died | 23 May 1929 La Seyne-sur-Mer, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | George Inness |

| Known for | Painter |

| Movement | Aesthetic art; Orientalist |

| Spouse(s) | (1) George Earle m. 1897 (2) Marie Felice Ranger m.1923 |

Biography

Early life with Cyrus Teed

Douglas Arthur Teed was born on February 21, 1860 to Fidelia M. Rowe and Cyrus R. Teed, in New Hartford, New York. At age nine, his father left the family to develop a religious sect called "Koreshanity" after experiencing what he claimed was a divine vision. While sitting in the laboratory where he practiced medicine and Alchemy, Cyrus reported "a relaxation at the... back part of the brain, and a peculiar buzzing tension at the forehead."[1] He claimed his soul left his body and witnessed a woman whom he perceived as "His Mother and Bride."[1] Cyrus Teed claimed this was a calling to spread the word on the true nature of our cellular cosmogony, and to bridge the gap between science and religion.[2] Cyrus described the messenger as:

"Gracefully pendant from the head, and falling in golden tresses of profusely luxuriant growth over her shoulders, her hair added to the adornment of her personal attractiveness. Supported by the shoulders and falling into a long train was a gold and purple colored robe. Her feet rested upon a silvery crescent; in her hand, and resting upon this crescent, was Mercury's Caduceus..."[3]

There was an awakening in the Teed household hinging on dogmatic opinions, mysticism, and the exotic. The family did not buy into the new lifestyle, however, and eventually the family lost Cyrus to the religious fervor which consumed him. Dr. Teed persisted in his beliefs, neglecting his duties at home, and eventually settled a communal colony called "The Koreshan Unity".

The American Eagle of August 1973 reports that letters from Cyrus Teed indicated affection for his wife and child, and in spite of criticism, Delia accepted him as the messianic personality of the age.[4] However, Douglas and his mother never converted. Due to ill health, she and Douglas moved in with her sister in Binghamton, New York. They remained there until Delia's death in 1885.

Painter

Douglas Arthur Teed began painting as a small boy in Utica having opened his own study by the age of fourteen. In his youth, Teed spent many hours in the studio of George Inness, whose tonalist landscapes greatly impressed the growing artist.[5] Teed lived in New York as a billboard painter until 1890.

Later that year he opened a studio in Rome. This would serve as the home base for his five-year study in Europe. Teed found "a land in which art had a tradition of hundreds of years of immense imaginative achievements, a lovely and dramatically varied countryside, great paintings of the past to inspire him, the accumulated magic and splendor of the past."[6] The popular trends in European art at that time are mirrored in his paintings.

Teed returned to his New York studio in 1895. He earned his living by paintings portraits and landscapes. Most of his work was sold to private collectors; often painting in trade of other services. During World War I, the bulk of Teed's income was supported by painting the portraits of such men as Senator O'Gorman of New York, Governor Whitman of New York, Judge Williams R. Day of the United States Supreme Court, and steel mogul Andrew Carnegie. Although highly praised at the time, portraits held little interest for Teed; when interviewed in 1925, he stated being "...off portraits for life."[7]

Through the years, his works adorned the walls of the Scranton Club, the Arlington Hotel, the Art Hall of the Koreshan Unity, the Arnot Art Museum, the 1911 International Exhibition in Rome, the Annual Exhibitions of Paintings by American Artists at the Detroit Institute of the Arts, the San Diego Fine Arts Gallery, the Oriental Theatre in Detroit, the Binghamton Public Library, and found a healthy market within the homes of the nouveau-riche Detroit industrialists. He's exhibited in Italy, Munich, London, Boston, Philadelphia, and the Royal Academy of Canada. Three canvases were purchased to decorate the reception chamber of the executive mansion in Albany during the governorship of Charles S. Whitman. Three others were purchased for the state armory.

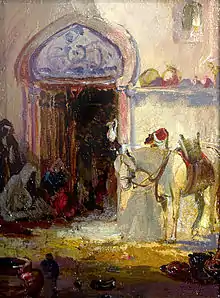

The first major retrospective of Islamic art had taken place in 1893 at the Palais de l'Industrie, while Teed was touring Europe. This was the first popular exposure of Islamic art to a newly industrialized Western world. Teed's oriental paintings dating prior to 1908 are likely to be studies of the works of popular European Orientalists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, whose colorful and romantic portraits of the Eastern world fascinated him.[8] In pursuit of first hand inspiration, Douglas Teed left to the Middle East in 1907.

Douglas Teed returned to the United States four years later. He reentered into an art world that was in a state of transition, where artists began publicly rebelling against the foreign domination of American art tastes. When Teed left to the Middle East, impressionism was still very popular in the markets. However, displays such as The Armory Show of 1913 presented the work of a new emerging culture; the European Modernists, along with the new the American Realists, (particularly the work of Arthur B. Davies and the other members of his movement, The Eight). Due to the isolation of his journey, Douglas Arthur Teed shared no involvement in the progression of the contemporary market's taste. He returned to the United States as a romantic painter of Oriental scenes still utilizing impressionist technique.

The patrons of the arts at this time in Detroit were primarily wealthy industrialists who leaned toward established art forms. Teed's more conservative, impressionistic depictions of the Middle East were well received, filling the drawing rooms of the city's elite.

In a 1924 review of the Annual Exhibition for American Artists, Mr. R. Poland (then Director of Education at the Detroit Institute of Arts) wrote, "...as to landscapes, Mr. Douglas Arthur Teed... has brought the beholder to intimate communion with nature. One looks into the very soul, radiant and smiling, of all humanity."[9] Three paintings entered the exhibition, one voting runner up for the Floyd G. Hitchcock prize, awarded by public vote. The painting was entitled, "Awaiting a Buyer". It received 153 votes, the winner received 154 votes, and was purchased before the completion of the show. In 1925 he received the largest number of public votes for his painting, "Argument as to Value".[10]

Teed continued to paint experimental works privately. He explored the female figure from the standpoint of her mysterious emotions, rather than emphasizing the anatomical. In another work, "The Light Worshipers" (1910), Teed attempts to combine Roman ruins with a sense of mysticism, developing forms and atmosphere inspired by the George Inness painting, The Monk.[11] One exhibition review from 1918 notes, "Douglas Arthur Teed, another unfamiliar exhibitor, shows four canvases. Three of them eccentricities in a pale white tone."[12]

In January 1928, ten Detroit artists, including Teed, held an independent exhibition at the Hurley Galleries, 111 East Kirby Street, in protest of the jury selection for the annual Michigan Artists Exhibition. Four "conservative" artists who were rejected by the jury were: Percy Ives, Francis Paulus, John Morse, and Charles Waltensperger. The six joining them in this show: Julius Rolshoven, William Greason, Alfred E. Peters, Roman Kryzonowsky, Joseph Gries, and Teed, "refrained from offering any work to the jury for much the same reason which prompted the rebellion -- a feeling that the annual Michigan show had grown less and less hospitable toward the more conservative painters."[13] The exhibition stirred up quite a controversy in the city. Mr. Samuel Halpert, a juror for the 1928 exhibition stated that "many of the... artists whose work was rejected by the jury have been dead for 20 years".[14] Mr. J. W. Young responded to this remark in an essay when he defended the 10 rebels as "Guardians of the City's Artistic Ideals".[15] Of the works represented by the ten artists at the Salon des Refusés, he stated that "those who like the work of Douglas Arthur Teed will find his 'landscape' quite out of his usual vein, and may well conclude that it is a pretty good picture for a dead living man to have painted."[15] Teed offered his opinion of the exhibition to the Detroit Free Press,

- "The Cubist, post-impressionists, the fellows who call themselves 'Ultimatists' and others classed as modernists have reverted to jungle art. They are quite free from an expose of knowledge of color, form, or any of the rudimentary principles of painting. One favorable feature of these groping young minds is that sometimes a development of the new features of art in which they are delving catches the mind of some exceptional man, who is able to couple his unusual culture with their theories, and the result is genius. Such men were Claude Monet, and earlier, Corot. So for the sake of one or two geniuses, the world must be patient with much worthless rubbish."[14]

Private life

Douglas Teed was married to George E.C. Earle on October 27, 1897. The couple took up residence in a studio in Hallstead, Pennsylvania overlooking the Susquehanna River. This studio, called "Teed's Castle" by locals,[16] was on the property of a wealthy diplomat in the foreign service, James T. DuBois. They spent the summers relaxing and entertaining guests in the twenty-seven room house on the mountain. Inside this house, which is still standing, the living room walls are covered by self-painted bucolic murals.

The Susquehanna County census for 1900 lists Teed, D. Arthur, occupation artist, and his wife, George, as owning a mortgaged farm house in Great Bend Township, Pennsylvania. The Teeds were devoted to one another and spent pleasant hours gathered with their friends. They were cultured yet relaxed people who entertained themselves by discussing books, art, and music. Often they would speak different languages for an evening or read. One Binghamton resident remembers Teed as a "democratic" person.[17] In the summer, their friends accompanied them to a country side farm house in Salt Springs, Pennsylvania. Teed would take his easel outdoors and the "gentle man with the mustache" would paint, while his wife sketched in water color. Teed exhibited a charming sense of humor in an anecdote from a Binghamton woman, who was a small girl at the time, "He named the out-house at Salt Springs the 'Spider Retreat'," she recalls.[18] She also remembered being impressed by the massive gold wedding ring which Douglas had designed for his wife, "It was adorned with beautiful cupids."[19]

On October 10, 1917, his wife, George Earl Teed, died. This prompted Teed's move to Detroit that same year. It was in Detroit where Teed's work gained recognition and began receiving higher prices.

In 1923, he married Marie Felice Ranger. Felice's sister described the couple as "cultured".[20] They participated in cultural activities and socialized by entertaining groups of fellow artists. During that time, Teed developed friendships with other well-known, more established Detroit artists.

In 1929, Douglas had a mild heart attack and was told not to go near his studio for six weeks. On May 23, 1929, Douglas Arthur Teed suffered a second heart attack and died while with his wife, at the age of 69.

Connection to Koreshanity

Douglas did seek out his father later in life. In 1905, he visited the Koreshan Unity. An article in the Fort Myers Press expressed gratitude toward south Florida receiving such a distinguished painter, and suggested the possibility of Teed remaining in the state to paint.[21] There are numerous accounts in the communal paper espousing the talents of the artist son of Koresh.[8] A special hall was built to house 27 of his works, which Teed painted especially for the commune. The people of the Unity were flattered by Teed's interpretation of Estero, and the uncharted surrounding Florida land. Many of these works were painted in an egg-tempera and have faded quite badly. Only a few oil paintings retain the artist's original intent.

One such painting, "Tropical Dawn"[22] was presented to a member of the Unity, Victoria Gratia, at her birthday celebration in April 1905.[8]

It seemed the relationship between father and son was a healthy one. Douglas even dedicated a poem to his father for his birthday (known to the Unity as "The Solar Festival") on October 18, 1905, entitled, The Lost Muse.[23] However, in 1907 Douglas sued the Koreshan Unity for overdue payment, citing the paintings which hung in the Art Hall.[23] In 1908, a full settlement was made out of court between Douglas and the Unity. That same year his father died.

The art of Teed

- "A picture should aim higher than to please the eye alone -- that it should be so high in its intent, so true in its treatment that all normal minds should be benefited and educated by it -- to this end has been a life of continuous study."

- -- Douglas Arthur Teed, Fort Myers Press, 1905

The success of Teed's work is based on compositional harmony and a powerful maintenance of color value. Early attempts at figure drawing, such as "Angel Rescue", reveal a frustration towards the articulate separation of the subject from its surroundings. Thus began his treatment of the figure as an element in space, casting subjects against the romantic landscape – a vibrant rush of environment acting as a reflection of temper.

Accurate depictions of foliage, included with the abounding beauty of the countryside, were utilized by American artists at the time to create an awe-inspiring mood in their works. These were aesthetic tenets made popular by Sir Edmund Burke's treatise anticipating classical Romanticism, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. As Teed refined his aesthetic, he began to approach his subjects less as strict anatomical studies, and more in the vein of the foliage of the classical American landscape—in a delicate application of paint; as the vision which guided his hand, immemorial. In a Teed painting, we are asked to witness a scene which has fallen into the atmosphere, and plays on the same brush-stroke as of the sand in the wind.

Teed successfully developed his own philosophy on the "problems of light" (concentration/diffusion),[24] popularized by the Barbizon artists. Many of his compositions are approached in concept of light. These techniques were first introduced to Teed by George Inness, in his own study as a disciple at the Barbizon School in Europe, starting in 1847.

The early influence of George Inness is clearly demonstrated within Teed's work; both practicing in a similar method, active in the same influences, emoting in the same key of atmospheric romanticism. Both Teed and Innes painted rapidly over wet paint. Teed was reported to have painted with a palette knife at great speed, able to produce a picture for a buyer in one night.[25]

Unfortunately, this manner of work causes the paint layers to dry at different rates, creating extensive cracking and paint loss in a relatively short time. This is true of many of Teed's works today.

Teed remained a deep admirer of the arts throughout his life. Teed exhibited specific interest and influence in the works of Antoine-Jean Gros, Henri Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-Léon Gérôme, George Inness, Claude Lorrain, Ludwig Löfftz, Eugène Joseph Verboeckhoven, and Jules Breton.

Teed studied every aesthetic style of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, continually searching for a successful means of conveying his passion; compelled to portray on canvas the spiritual aura. He brought himself to the reaches of the planet in search of the mystics in Nature. Teed wanted to symbolize a reverence for God and Nature; he wanted to convey allegorical messages; he wanted his paintings to become his visual poetry.

Douglas Teed lived a quiet and humble life, never exhibiting the eccentric follies of the acclaimed masters he admired. His quiet did not mark a languid heart. There is a consistent temperament throughout his work, experienced strongest when seen in succession; a disconnected world, brooding and melancholy. In an article entitled "Distinguished Artist at Estero" (1905), one reviewer noted his painting's "...gravity of presence. With Mr. Teed, each image appears captured moments before the storm."[26]

Upon his return from Europe, Teed's canvases became highly acclaimed for their charm. The Boston Evening Transcript calls Teed "a man of high ambitions, with a fine sense of color, a just appreciation of values and a close observer of the subtle and delicate variations of the sensitive gamut... Rather than concentrate on specific forms, the artist has developed an overall pattern of color, light, and impasto which adds cohesiveness to the compositions."[27]

His work no longer depicted simply the local morning picturesque. His landscapes were used as mirrors of his own complexion, both an interpretation of Nature's inner-spirit and his own. He staged "worlds of atmosphere, looking forth at us through ethereal light, through shadows..."[28] Although he never chose to alleviate realistic representation altogether, Teed's paintings were largely the product of a passionate imagination, whose emotions materialized in the works' creation. The landscape had become subordinated to the thought.

There is a preference for the mystic and the exotic in his work. Early in his childhood, Douglas was exposed to various beliefs and theories through the oration of his father. No doubt, the vision Cyrus experienced concerning the Mother-Bride deity created an impression on the imagination of the young man. Both Cyrus and Douglas shared a propensity for idealism and didactic pursuits. There is a strong echo of Cyrus Teed's dogma in the work of his son.

Ultimately, Teed spent his entire life searching; through an emotional expression on the canvas, for inspiration in his travels around the world, in improvement of his method and evolution of style – searching for a "frankness and simplicity", stating, "simplicity is the most difficult of all things."[29] He stands as an example of the continuous strain of romanticism used by American artists; heirs to the deep-seated religious, cultural, and intellectual convictions of a young nation founded on visionary daring and integrity.

Teed left behind twenty unfinished paintings when he died in 1929.[30]

- "Money did not make the Barbizon school; rather, ability placed its members among the Immortals... Pictures may be good art and yet be unlike natural aspects as seen by you and me. Someone else may have 'visions' and may interpret them harmoniously, and with new departure keep within the artistic confines. Poetic feeling carries the painter higher than cold, rational appreciation; though something of both is required to obtain the highest success. Finally -- it takes more than one masterpiece to make a master."[28]

The work of Douglas Arthur Teed is currently housed in the Koreshan State Historic Site, the Arnot Art Museum, and countless private collections around the world.

Gallery

Poseidon, 1911

Poseidon, 1911 Dreaming, 1905

Dreaming, 1905 The Sultan, 1910

The Sultan, 1910 Panorama #1, 1907

Panorama #1, 1907

See also

References

- Robert Lynn Rainard, "In the Name of Humanity -- The Koreshan Unity," University of South Florida, p.5

- Robert Lynn Rainard, "In the Name of Humanity -- The Koreshan Unity," University of South Florida, p.6

- Howard David Fine, "The Koreshan Unity: The Early New York Beginnings of a Utopian Community,", p.5

- Hedwig Michel, "The Koreshan Unity Settlement," The American Eagle, August 1973

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.17

- The Detroit Institute of Arts and the Toledoa Museum of Art, Travelers in Arcadia: American Artists in Italy, 1830-1875, (1951), p.12

- "Douglas Arthur Teed", Bonstelle Playhouse Program, February 23, 1925

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.29

- R. Poland - Director of Education at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit Sunday Night', February 23, 1924

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.40

- "The Monk"

- Detroit Free Press, January 20, 1918 (exhibition review)

- "Art Colony in Revolt Plan Rival Exhibit," Detroit Free Press, January 8, 1928

- "Artists Assail Jury for Exhibit Choices," Detroit Free Press, January 8, 1928

- J.W. Young, "Rejected Painters Open Rival Show Near Institute," Detroit Free Pres, January 15, 1928

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.26

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.38

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.27

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.28

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.41

- Lucie Page Borden, "Distinguished Artist at Estero," The Flaming Sword, May 30, 1905, p.13

- "Tropical Dawn" Archived July 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.15

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.36

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p.19

- Lucie Page Borden, "Distinguished Artist at Estero", The Flaming Sword, May 30, 1905, p.13

- Lucie Page Borden, Fort Myers Press (Fort Myers, 1905), as quoted in the Boston Transcript

- "Fine Picture on Exhibition", Elmira Star Gazette, May 7, 1913

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p. 37

- Pamela Beecher, Douglas Arthur Teed: An American Romantic, (1982), p. 44