Duffus Castle

Duffus Castle, near Elgin, Moray, Scotland, was a motte-and-bailey castle and was in use from c.1140 to 1705. During its occupation it underwent many alterations. The most fundamental was the destruction of the original wooden structure and its replacement with one of stone. At the time of its establishment, it was one of the most secure fortifications in Scotland. At the death of the 2nd Lord Duffus in 1705, the castle had become totally unsuitable as a dwelling and so was abandoned.[1]

| Duffus Castle | |

|---|---|

| Duffus, Nr Elgin, Moray, Scotland | |

| |

| Coordinates | 57°41′16″N 3°21′41″W |

| Type | First castle: wood - Motte-and-bailey Second castle: stone - keep with curtain wall |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Historic Environment Scotland |

| Open to the public | Yes — No entry fee |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1140 & 1305 |

| Built by | First castle: Freskin, of Strabrock and DuffusSecond castle: Sir Reginald le Chen |

| In use | c.1140 to 1705 |

| Materials | Local stone, sandstone |

| Designated | 27 September 1996 |

| Reference no. | SM90105 |

| Category | Secular |

The wooden castle

Oengus, Mormaer of Moray, led a rebellion against David I, King of Scots in 1130. After Oengus' defeat and death in battle, David installed Freskin, a nobleman probably of Flemish origin, as his chief agent in Moray,[2] and he was probably the first to build a castle at Duffus.

Freskin’s background is uncertain. The consensus amongst historians is that he was of Flemish background, the principal argument being that "Freskin" is a Flemish name.[3] Undoubtedly, King David, himself a Normanised magnate with extensive estates in northern England and Normandy, granted lands to many nobles from Flanders as well as Normans. The unlikely alternatives are that he may have been an Anglo-Saxon or a Scot who fought for King David and his English general Edward Siwardsson in Moray. At that time, when Flemish nobles were referred to in writs by nationality (almost never), they were styled "Flandrensis".[4] Freskin appears in no contemporary sources, and was never referred to by his national origin. Regardless of his origin, by the 13th century his descendants were referring to themselves as 'de Moravia' ('of Moray') and had become one of the more powerful families in northern Scotland.[5]

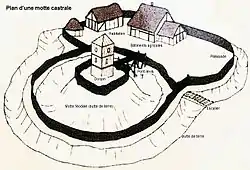

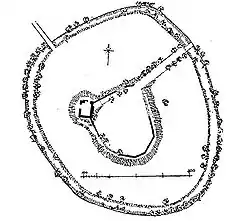

It was Freskin who built the great earthwork and timber motte-and-bailey castle in c. 1140 on boggy ground in the Laich of Moray. It was certainly in existence by the time the king came to visit in 1151.[6] The motte was a man-made mound with steeply sloping sides and a wide and deep ditch that surrounded the base. Timber buildings would have stood on its flat top and would have been further protected by a wooden palisade placed around the edge of the summit. The motte was accessed from the bailey. This is a wide stretch of earth elevated above the surrounding area but not as high as the motte. At Duffus, the motte would have been reached by steps set into the mound. The bailey contained the buildings necessary to sustain its inhabitants – brew and bake houses, workshops and stables – as well as the living accommodation.

The castle may have been destroyed in 1297[7] during a rebellion against English rule in the region,[8] and it might have suffered further during Robert the Bruce's campaign in Moray in 1306.

The stone castle

In 1270, the castle passed into the ownership of Sir Reginald le Chen (d.1312) through marriage to the heiress Mary de Moravia, a descendant of Freskin. With the death of Reginald le Chen of Duffus in 1345, Duffus passed to his daughter Mariot who was married to Nicholas, the second son of Kenneth de Moravia, 4th Earl of Sutherland. The Sutherlands themselves were descended from Freskin and the castle remained in their possession until 1705[5] when it was abandoned.

In 1305, it was recorded that Reginald le Chen received a grant from King Edward I of England of 200 oaks from the royal forests of Longmorn and Darnaway "to build his manor of Dufhous"[9] demonstrating that a large construction project was being carried out. The wood could have been needed for scaffolding, flooring and roofing of a new stone fortress. Alternatively, the stone structure, which dates from the early 14th century,[7] could have been built by the younger Reginald.

A two-storey rectangular tower was built on the motte and was the main residence. The first floor held the lord's hall, with a latrine and bed chambers. The ground floor was the main storage space and also accommodated the lord’s household. The tower was built as a defensive structure with a small number of narrow windows. There was only the one entrance on the ground floor which also housed a portcullis. On the second floor, two doors exited onto the walkway of the curtain wall. This wall completely enclosed the bailey. The put-log holes built into the curtain wall indicate the presence of a number of buildings. On the north side a later building was erected that housed a kitchen, a great hall with reception room and the great chamber bedroom. It is possible that this building was constructed by the Sutherlands. It is not known when the serious subsidence took place but evidence of repairs to the tower are evident before it slid down the motte. The tower shows no further repairs and may have collapsed early on but the newer hall became the main residence. This building shows continued alterations over time. In 1689, John Graham, 1st Viscount of Dundee was a guest of Lord Duffus just before the Battle of Killiecrankie, and would be one of the last important visitors before the castle’s abandonment.[10]

Notes

- MacGibbon, D & Ross, T 1887 The Castellated and Domestic Architecture of Scotland, vol 1. Edinburgh

- Oram, Richard (1999). "David I and the Scottish Conquest and Colonisation of Moray". Northern Scotland. 19: 1–19.

- See G.W.S. Barrow, "The Beginnings of Military Feudalism" in Barrow (ed.) The Kingdom of the Scots, 2nd Ed. (2003), p. 252, n. 16.

- Gray, James 1922 Sutherland and Caithness in Saga-Time or, the Jarls and the Freskyns. Edinburgh

- Balfour Paul, J 1906 & 1911 The Scots Peerage. Edinburgh

- Ritchie, Anna; Ritchie, James Neil Graham (1998). Scotland: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-19-288002-4.

- Cruden, Stewart (1981). The Scottish Castle. p. 126.

- Simpson, W. Douglas (2013), "The castles of Duffus, Rait, and Morton reconsidered" (PDF), The Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Archaeology Data Service, 92: 13

- Bain, J (ed) 1888 Calendar of Documents relating to Scotland, Vol IV. Edinburgh.

- Shaw, L & Gordon, J 1882 The History of the Province of Moray, vol 2. Edinburgh

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duffus Castle. |