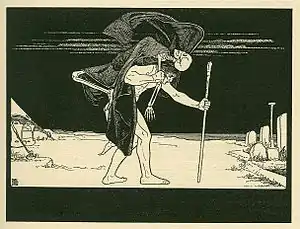

Dybbuk

In Jewish mythology, a dybbuk (Yiddish: דיבוק, from the Hebrew verb דָּבַק dāḇaq meaning 'adhere' or 'cling') is a malicious possessing spirit believed to be the dislocated soul of a dead person. It supposedly leaves the host body once it has accomplished its goal, sometimes after being helped.[1][2][3]

Etymology

Dybbuk is an abbreviation of דיבוק מרוח רעה dibbūq mē-rūaḥ rā‘ā ('a cleavage of an evil spirit'), or דיבוק מן החיצונים dibbūq min ha-ḥīṣōnīm ('dibbuk from the outside'), which is found in man. Dybbuk comes from the Hebrew word דִּיבּוּק dibbūq which means 'the act of sticking' and is a nominal form derived from the verb דָּבַק dāḇaq 'to adhere' or 'cling'.[4]

History

The term first appears in a number of 16th century writings,[1][5] though it was ignored by mainstream scholarship until S. Ansky's play The Dybbuk popularised the concept in literary circles.[5] Earlier accounts of possession (such as that given by Josephus) were of demonic possession rather than that by ghosts.[6] These accounts advocated orthodoxy among the populace[1] as a preventative measure. For example, it was suggested that a sloppily made mezuzah or entertaining doubt about Moses' crossing of the Red Sea opened one's household to dybbuk possession. Very precise details of names and locations have been included in accounts of dybbuk possession. Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, the Satmar rebbe (1887–1979), is reported to have supposedly advised an individual said to be possessed to consult a psychiatrist.[6]

Ansky's play is a significant work of Yiddish theatre, and has been adapted a number of times by writers, composers and other creators including Jerome Robbins/Leonard Bernstein and Tony Kushner. In the play, a young bride is possessed by the ghost of the man she was meant to marry, had her father not broken a marriage-agreement.

There are other forms of soul transmigration in Jewish mythology. In contrast to the dybbuk, the ibbur (meaning "impregnation") is a positive possession, which happens when a righteous soul temporarily possesses a body. This is always done with consent, so that the soul can perform a mitzvah. The gilgul (Hebrew: גלגול הנשמות, literally 'rolling') puts forth the idea that a soul must live through many lives before it gains the wisdom to rejoin with God.

In psychological literature the dybbuk has been described as a hysterical syndrome.[7]

In popular culture

Film

Michał Waszyński's 1937 film The Dybbuk, based on the Yiddish play by S. Ansky, is considered one of the classics of Yiddish film-making.[8]

In Love and Death, Woody Allen's 1975 satire of Russian literature, Boris (Allen) flirts with the Countess Alexandrovna (Olga Georges-Picot), who is attending an opera with her lover Anton Ivanovich Lebedokov (Harold Gould). When the Countess says to Boris "You must visit me for tea. I'm sure we'd have a lot to talk about," Boris says "What about the dybbuk?"

In the 1997 Christopher Guest film Waiting for Guffman, dentist Allan Pearl discusses his family history with show business: "I think I got a, a, an entertaining bug... from my grandfather... uh, Chaim Pearlgut, who was very very big in the, um, Yiddish, uh, theater, back in New York. He was in the, the very... the sardonically irreverent ..."Dybbuk Shmybbuk, I Said 'More Ham'"... and that revue I believe was 1914, and that revue was what made him famous. Incidentally, the song 'Bubbe Made a Kishke' came from that revue."

The dybbuk was featured as the main antagonist in the horror films The Unborn (2009), The Possession (2012) and Ezra.

A Serious Man opens with a parable about a couple who suspect that the rabbi they are hosting for dinner is a dybbuk.

Marcin Wrona's Demon is the story of a groom possessed by a dybbuk the night before his wedding.

The Malayalam film Ezra (2017) revolves around a dybbuk box, with references to Kabbalist traditions and occultism. In the film To Dust (2018) the protagonist is suspected by his children to be possessed by a dybbuk.

The dybbuk was also the main antagonist in the short film Dibbuk (2019) directed by Dayan D. Oualid. The film deals with an exorcism within the Parisian Jewish community.[9]

The dybbuk was mentioned in the film Killer Sofa (2019) about a killer recliner possessed by a dybbuk.

Music

In March 2020, the horror punk band Voice of Doom released the song The Dybbuk on the album Horror Punks USA Quarantine Compilation 2020, Volume 1.[10]

Print

In Romain Gary's 1967 novel The Dance of Genghis Cohn, a concentration camp warden is haunted by the dybbuk of one of his victims.[11]

In Ellen Galford's 1993 novel The Dyke and the Dybbuk, lesbian taxi-driver Rainbow Rosenbloom is haunted by, and gets the better of, a female dybbuk haunting her as a result of a curse placed on her ancestor 200 years ago.[6]

The dybbuk appears in the novel, The Inquisitor's Apprentice (2011) by Chris Moriarty.[12]

In the comic series Girl Genius, the forcible insertion of the mind of Agatha's mother, the main villain Lucrezia Mongfish/"The Other", into her own was compared to a dybbuk by one of her followers when reporting the situation to someone else.

Richard Zimler's 2011 novel The Warsaw Anagrams is narrated by a dybbuk desperately trying to understand why he has remained in our world. This is in keeping with kabbalistic belief that dybbuks fail to pass over to the Other Side because of a mitzvah or duty that they have failed to fulfil.

Television

Sidney Lumet directed "The Dybbuk", an episode of The Play of the Week based on the play by S. Ansky adapted into English by Joseph Liss. It aired on October 3, 1960.[13]

The dybbuk is mentioned in the paranormal TV show Paranormal Witness, season 2, episode 4, "The Dybbuk Box" (USA 2012).

The "Dybbuk Box" was shown on the first episode of Deadly Possessions (spin off of Ghost Adventures), in which the son of the relative of a Holocaust survivor recounts the tale of the dybbuks' alleged involvement in the deaths surrounding the box.

Two dybbuk boxes were shown in the fourth and final episode of Ghost Adventures: Quarantine in which Zak Bagans opens both boxes resulting in him acting strangely aggressive towards other members of the crew.

In the TV show Difficult People, season 3, episode 3 "Code Change", Billy helps his sister-in-law Rucchel exorcise what she believes to be a dybbuk from her basement.

In the episode of The Real Ghostbusters titled "Drool, the Dog-faced Goblin", the Ghostbusters discuss with Peter Venkman the many different forms an antagonistic ghost they are facing can take, with Egon Spengler mentioning a dybbuk. In a later episode titled "The Devil to Pay", the Ghostbusters deal with a demon named Dib Devlin, who swindles Ray Stanz and Winston Zeddemore into selling their souls to compete in his game show. Dib Devlin is later revealed to be a dybbuk.

Grandpa Boris tells a scary story to the babies involving a dybbuk in an early episode of Rugrats.

In the Legends of Tomorrow episode "Hell No, Dolly", the team goes after a dybbuk (voiced by Paul Reubens) stuck in a creepy doll, using the alias "Mike the Spike". The dybbuk later inhabits a puppet of Martin Stein. By the end of the next episode, "Mike the Spike" is subdued by the Legends and detained at the Time Bureau.

In the sixth episode of the third season of The Good Fight, Marissa Gold (played by Sarah Steele) refers to a particularly devilish and disruptive character as a "dybbuk in a suit."

In the seventh episode of the second season of Documentary Now!, "He'll chase the Dybbuk right out of your room." is a phrase from the film Detective Rabbi.

Theater

Few topics in Jewish theater history have inspired as many stage treatments as the dybbuk. A review of the innovative approaches to the subject was presented by EgoPo Classic Theater in English translation from the Yiddish, as penned by Joachim Neugroschel and adapted by Tony Kushner, the production directed by Lane Savadove.[14] Containing detailed background information on the history of the dybbuk, "'Don't ask me what happened. It’s best not to know!': A DYBBUK, or Between two worlds"[15] the article was first published by All About Jewish Theatre[16] the world's largest English-language Jewish theater website, before its demise in 2014, but recently rescued by Drama Around the Globe[17] and republished by Phindie.[18]

See also

References

- Avner Falk (1996). A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 538. ISBN 9780838636602.

- "Dybbuk", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 10 June 2009

- Gershom Scholem. "Dibbuk". Encyclopedia Judaica.

- See A. Sáenz-Badillos & J. Elwolde, A History of the Hebrew Language, 1996, p. 187 on the qiṭṭūl pattern.

- Spirit Possession in Judaism: Cases and Contexts from the Middle Ages to the Present, by Matt Goldish, p.41, Wayne State University Press, 2003

- Tree of Souls:The Mythology of Judaism, by Howard Schwartz, pp. 229–230, Oxford University Press, 1 Nov 2004

- Billu, Y; Beit-Hallahmi, B (1989). "Dybbuk-Possession as a hysterical symptom: Psychodynamic and socio-cultural factors". Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Science. 26 (3): 138–149. PMID 2606645.

- "The Dybbuk". The National Center for Jewish Film. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Dibbuk (2019)". www.unifrance.org (in French). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "The Dybbuk", Horror Punks USA Quarantine Compilation 2020, Volume 1, retrieved 4 April 2020

- Schwartzv, Howard (1998). Reimagining the Bible: The Storytelling of the Rabbis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195104998.

- Bird, Elizabeth. "Books About Young Crimefighters in New York". Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Hoberman, J., The Dybbuk. Port Washington, NY: Entertainment One U.S. LP, 2011.

- Lane Savadove

- "'Don't ask me what happened. It’s best not to know!': A DYBBUK, or Between two worlds"

- All About Jewish Theatre

- Drama Around the Globe

- Phindie

Further reading

- J. H. Chajes, Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Aug 31, 2011.

- Rachel Elior, Dybbuks and Jewish Women in Social History, Mysticism and Folklore, Urim Publications, 1 Sep 2008.

- Fernando Peñalosa, The Dybbuk: Text, Subtext, and Context. Jan 2013.

- Fernando Peñalosa. Parodies of An-sky's The Dybbuk. Nov 2012

- Yosl Cutler, "The Dybbuk in the Form of a Crisis", In Geveb, March 2017.

External links

- "The Dybbuk" by Ansky Jewish Heritage Online Magazine

- "Dybbuk—Spiritual Possession and Jewish Folklore" by Jeff Belanger, Ghostvillage.com

- "Dybbuk", Encyclopædia Britannica

- Dibbuk short film teaser

- ডিব্বুক (Dybbuk) - Bengali horror fiction based on Dybbuk myth by Tamoghna Naskar. Publisher - Aranyamon Prokashoni https://www.aranyamon.com/