EEG microstates

EEG microstates are transient, patterned, quasi-stable states or patterns of an electroencephalogram. These tend to last anywhere from milliseconds to seconds and are hypothesized to be the most basic instantiations of human neurological tasks, and are thus nicknamed "the atoms of thought".[1] Microstate estimation and analysis was originally done using alpha band activity, though broader bandwidth EEG bands are now typically used.[2] The quasi-stability of microstates means that the "global [EEG] topography is fixed, but strength might vary and polarity invert."[3]

History

The concept of temporal microstates of brain electrical activity during no-task resting and task execution (event-related microstates) was developed by Dietrich Lehmann and his collaborators (The KEY Institute for Brain-Mind Research, University of Zurich, Switzerland) between 1971 and 1987,[4][5][6]( see "EEG microstates". Scholarpedia.) Drs. Thomas Koenig (University Hospital of Psychiatry, Switzerland) and Dietrich Lehmann (KEY Institute for Brain-Mind Research, Switzerland)[1] are often credited as the pioneers of EEG Microstate analysis.[2] In their 1999 paper in the European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience,[1] Koenig and Lehmann had been analyzing the EEGs of those with schizophrenia, in order to investigate the potential basic cognitive roots of the disorder. They began to turn their attention to the EEGs on a millisecond scale. They determined that both normal subjects and those with schizophrenia shared these microstates, but they varied in characteristics between the two groups, and concluded that:

- "Momentary brain electric field configurations are manifestations of momentary global functional state of the brain. Field configurations tend to persist over some time in the sub-second range ("microstates") and concentrate within few classes of configurations. Accordingly, brain field data can be reduced efficiently into sequences of re-occurring classes of brain microstates, not overlapping in time. Different configurations must have been caused by different active neural ensembles, and thus different microstates assumedly implement different functions."[1]

Identifying and analyzing microstates

From EEG to microstate

Isolating and analyzing one's EEG microstate sequence is a post-hoc operation that typically utilizes several averaging and filtering steps. When Koenig and Lehman ran their experiment in 1999 they constructed these sequences by starting from a subject's eyes-closed resting state EEG. The first several event-free minutes of the EEG were isolated, then periods of around 2 seconds each were refiltered (Band-pass ≈ 2–20 Hz). Once the epochs were filtered, these microstates were analytically clustered into mean classes via k-means clustering, post hoc.[7] A probabilistic approach, using Fuzzy C-Means, to clustering and subsequent assigning (see below) of microstates has also been proposed.[8]

Clustering and processing

Since the brain goes through so many transformations in such short time scales, microstate analysis is essentially an analysis of average EEG states. Koenig and Lehmann set the standard for creating classes, or recurrent averaged EEG configurations. Once all the EEG data is collected, a "prototype" EEG segment is chosen, with which to compare all other collected microstates. This is how the averaging process starts. Variance from this "prototype" is computed to either add it to an existing class, or to create a separate class. After similar configurations are "clustered" together, the process of selecting and comparing a "prototype" is repeated several times for accuracy. The process is described in more detail by Koenig and Lehmann:

"Similarity of EEG spatial configuration of each prototype map with each of the 10 maps is computed using the coefficient of determination to omit the maps' polarities. ...Separately for each class the prototype maps are updated combining all assigned maps by computing the first spatial principal component[7] of the maps and thereby maximizing the common variance while disregarding the map polarity." This process is repeated several times using different randomly selected prototype maps from among the collected data to use for statistical comparison and variance determination.[7]

Creating and assigning classes

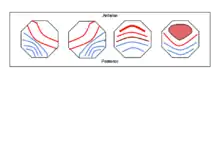

Most studies[1][9][10][11][12][13][14] reveal the same 4 classes of microstate topography:

- A: right-frontal to left-posterior

- B: left-frontal to right-posterior

- C: frontal to occipital

- D: mostly frontal and medial to slightly less occipital activity than class C

However, many studies have also found other EEG microstate template maps that are likely to be meaningful.[15] converged on 16 maps to explain a high proportion of the observed variance.[16] found 13 maps using an ICA approach. The number of microstates 'found' and used is partly a function of the cognitive state of the person, but also partly the method used to cluster and assign microstates. Though microstates have historically always been assigned deterministically, recent work has also suggested that there are computational, analytical and conceptual issues that may be addressed through a probabilistic analysis of microstates.[8]

Applications

Basic understanding of human cognition

It is the current hypothesis that EEG Microstates represent the basic steps of cognition and neural information processing in the brain, but there is still much research that needs to be done to cement this theory.

Koenig, Lehmann et al. 2002 [17]

This study investigated EEG Microstate variance across normal humans of varying ages. It showed a "lawful, complex evolution with age" [17] with spikes in mean microstate duration around ages 12, 16, 18, and 40–60 years, suggesting that there is significant cerebral evolution occurring at those ages.[17] As for the cause of this, they hypothesized that it was due to the growth and restructure of neural pathways,

- "In studies on the micro-architecture of developing brain tissue, it has been observed that after an initial excess of relatively unorganized synaptic connections, the number of synapses gradually decreased, while the degree of organization of the connections increased (Huttenlocher, 1979; Rakic et al., 1986). It is thus more likely that the observed changes in microstate profile result form the elimination of non-functional connections rather than from the formation of new ones. Another possible relation of the present results with neurobiological processes comes from the observation that with increasing age, asymmetric microstates diminish, while symmetric microstates increase. Assuming that asymmetric microstates result from predominantly unilateral brain activity, while symmetric microstates indicate predominantly bilateral activity, the observed effects may be related to the growth of the corpus callosum, which continues until late adolescence (e.g., Giedd et al., 1999)." [17]

Van De Ville, Britz, and Michel, 2010 [3]

In a study conducted by researchers in Geneva, the temporal dynamics and possible fractal properties of EEG microstates were analyzed in normal human subjects. Since microstates are a global topography, but occur on such small time scales and change so rapidly, Van De Ville, Britz, and Michel hypothesized that these "atoms of thoughts" are fractal-like in the temporal dimension. That is, whether scaled-up or scaled-down, an EEG is itself a composition of microstates. This hypothesis was initially illuminated by the strong correlation between the rapid time scale and transience of EEG microstates and the much slower signals of a resting state fMRI.

- "The connection between EEG microstates and fMRI resting state networks (RSNs) was established by convolving the time courses of the occurrence of the different EEG microstates with the hemodynamic response function (HRF) and then using these as regressors in a general linear model for conventional fMRI analysis. Because the HRF acts as a strong temporal smoothing filter on the rapid EEG-based signal, it is remarkable that statistically significant correlations can be found. The fact that this smoothing did not remove any information-carrying signal from the microstate sequence and that furthermore the original microstate sequences and the regressors show the same relative behavior at temporal scales about two orders of magnitude apart suggests that the time courses of the EEG microstates are scale invariant."

This scale-invariant dynamic is the strongest characteristic of a fractal, and since microstates are indicative of global neuronal networks, it is justifiable to conclude that these microstates exhibit temporally monofractal (one-dimensional fractal) behavior. From here we can see the possibility that fMRI, which is also a global topography measure, is possibly just a scaled-up manifestation of its microstates, and thus further supports the hypothesis that EEG microstates are the fundamental unit of one's global cognitive processing.

Psychological pathologies

Comparing the EEG microstate classes between controls and those with psychosis has yielded important results, suggesting that the basic resting-state of those with psychosis is irregular. This implies that before any information is processed or created, it is bound to the dynamics of the irregular microstate sequencing.[1][9][10][11][12][13][14] Although microstate analysis has great potential to help understand the basic mechanisms of some neurological diseases, there is still much work and understanding that needs to be developed before it can be a widely accepted diagnostic.[2]

Schizophrenia

Numerous studies have investigated the temporal dynamics of EEG microstates in people with schizophrenia.[1][18][19][20][21] In the first study comparing the temporal dynamics of the EEG microstates in those with schizophrenia against healthy controls, Koenig and Lehmann reported that those with schizophrenia tend to spend too much time in microstate Class A compared to controls.[1] However, other studies in schizophrenia research have suggested a different picture. A meta-analysis comprising studies from 1999 to 2015 revealed that microstate class C occurred more frequently and for longer durations in those with schizophrenia than controls, while microstate class D occurred less frequently and for shorter durations.[22] These results were also confirmed by a later meta-analysis.[21] Similar abnormalities were reported in a study with adolescents with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, a population that has a 30% risk of developing psychosis.[18] Classes C and D abnormalities were also found in unaffected siblings of those with schizophrenia,[21] which prompted the authors to suggest that dynamics of microstates C and D are a candidate endophenotype for schizophrenia.

Panic disorder

In July 2011, Dr. Koenig collaborated with researchers from Kanazawa University in Japan, and others from the University of Bern in Switzerland, to do a microstate analysis on people with panic disorder (PD). They found that these people spent too much time in the same right-anterior to left-posterior microstate as in the schizophrenia studies.[9] This suggests temporal lobe malfunction, which has been reported in fMRI studies of those with PD; they spent an average of 9.26 milliseconds longer in this microstate than did control subjects. These aberrant microstate sequences are very similar to those in the schizophrenia study, and as anxiety is commonly found in schizophrenia, it may indicate a strong correlation between different severities of neurological pathologies and a person's microstate sequence.

Sleep analysis

In 1999, Cantero, Atienza, Salas, and Gómez studied alpha rhythms in normal human subjects in 3 states: eyes closed/relaxing, drowsiness at sleep onset, and REM sleep. They found that the mean determined microstate classes were different amongst consciousness states on 3 different parameters.[23]

- Mean microstate duration was longer during eyes-closed relaxation than the other 2 states

- Total number of microstates per second was greatest during drowsiness at sleep onset

- The number of classes determined was also greatest during drowsiness at sleep onset [23]

This study illuminates the complexity of brain activity and EEG dynamics. The data suggest that "alpha (wave) activity could be indexing different brain information in each arousal state."[23] Furthermore, they suggest that the alpha rhythm could be the "natural resonance frequency of the visual cortex during the waking state, whereas the alpha activity that appears in the drowsiness period at sleep onset could be indexing the hypnagogic imagery self-generated by the sleeping brain, and a phasic event in the case of REM sleep."[23] Another claim is that longer periods of stable brain activity may be handling smaller amounts of information processing, and thus few changes in microstates, while shorter, less-stable brain activity may reflect large amounts of different information to process, and thus more microstate changes.

See also

- List of neurological disorders

References

- Koenig T, Lehmann D, Merlo MC, Kochi K, Hell D, Koukkou M (1999). "A deviant EEG brain microstate in acute, neuroleptic-naive schizophrenics at rest". European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 249 (4): 205–11. doi:10.1007/s004060050088. PMID 10449596. S2CID 9107646.

- Isenhart, Robert. "The State of EEG Microstates." Online interview. 26 Sept. 2011.

- Van de Ville D, Britz J, Michel CM (October 2010). "EEG microstate sequences in healthy humans at rest reveal scale-free dynamics" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (42): 18179–84. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10718179V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007841107. PMC 2964192. PMID 20921381.

- Lehmann D (November 1971). "Multichannel topography of human alpha EEG fields". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 31 (5): 439–49. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(71)90165-9. PMID 4107798.

- Lehmann D, Skrandies W (June 1980). "Reference-free identification of components of checkerboard-evoked multichannel potential fields". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 48 (6): 609–21. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(80)90419-8. PMID 6155251.

- Lehmann D, Ozaki H, Pal I (September 1987). "EEG alpha map series: brain micro-states by space-oriented adaptive segmentation". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 67 (3): 271–88. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(87)90025-3. PMID 2441961.

- Pascual-Marqui RD, Michel CM, Lehmann D (July 1995). "Segmentation of brain electrical activity into microstates: model estimation and validation". IEEE Transactions on Bio-Medical Engineering. 42 (7): 658–65. doi:10.1109/10.391164. PMID 7622149. S2CID 12736057.

- Dinov M, Leech R (2017). "Modeling Uncertainties in EEG Microstates: Analysis of Real and Imagined Motor Movements Using Probabilistic Clustering-Driven Training of Probabilistic Neural Networks". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 11: 534. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2017.00534. PMC 5671986. PMID 29163110.

- Kikuchi M, Koenig T, Munesue T, Hanaoka A, Strik W, Dierks T, et al. (2011). Yoshikawa T (ed.). "EEG microstate analysis in drug-naive patients with panic disorder". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e22912. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...622912K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022912. PMC 3146502. PMID 21829554.

- Kindler J, Hubl D, Strik WK, Dierks T, Koenig T (June 2011). "Resting-state EEG in schizophrenia: auditory verbal hallucinations are related to shortening of specific microstates". Clinical Neurophysiology. 122 (6): 1179–82. doi:10.1016/j.clinph.2010.10.042. PMID 21123110. S2CID 7269365.

- Lehmann D, Faber PL, Galderisi S, Herrmann WM, Kinoshita T, Koukkou M, et al. (February 2005). "EEG microstate duration and syntax in acute, medication-naive, first-episode schizophrenia: a multi-center study". Psychiatry Research. 138 (2): 141–56. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.05.007. PMID 15766637. S2CID 24984292.

- Stevens A, Lutzenberger W, Bartels DM, Strik W, Lindner K (January 1997). "Increased duration and altered topography of EEG microstates during cognitive tasks in chronic schizophrenia". Psychiatry Research. 66 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(96)02938-1. PMID 9061803.

- Strelets V, Faber PL, Golikova J, Novototsky-Vlasov V, Koenig T, Gianotti LR, et al. (November 2003). "Chronic schizophrenics with positive symptomatology have shortened EEG microstate durations". Clinical Neurophysiology. 114 (11): 2043–51. doi:10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00211-6. PMID 14580602.

- Strik WK, Chiaramonti R, Muscas GC, Paganini M, Mueller TJ, Fallgatter AJ, et al. (October 1997). "Decreased EEG microstate duration and anteriorisation of the brain electrical fields in mild and moderate dementia of the Alzheimer type". Psychiatry Research. 75 (3): 183–91. doi:10.1016/s0925-4927(97)00054-1. PMID 9437775.

- Britz J, Díaz Hernàndez L, Ro T, Michel CM (2014). "EEG-microstate dependent emergence of perceptual awareness". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 8: 163. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00163. PMC 4030136. PMID 24860450.

- Yuan H, Zotev V, Phillips R, Drevets WC, Bodurka J (May 2012). "Spatiotemporal dynamics of the brain at rest--exploring EEG microstates as electrophysiological signatures of BOLD resting state networks". NeuroImage. 60 (4): 2062–72. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.031. PMID 22381593. S2CID 10712820.

- Koenig T, Prichep L, Lehmann D, Sosa PV, Braeker E, Kleinlogel H, et al. (May 2002). "Millisecond by millisecond, year by year: normative EEG microstates and developmental stages". NeuroImage. 16 (1): 41–8. doi:10.1006/nimg.2002.1070. PMID 11969316. S2CID 572593.

- Tomescu MI, Rihs TA, Roinishvili M, Karahanoglu FI, Schneider M, Menghetti S, et al. (September 2015). "Schizophrenia patients and 22q11.2 deletion syndrome adolescents at risk express the same deviant patterns of resting state EEG microstates: A candidate endophenotype of schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research. Cognition. 2 (3): 159–165. doi:10.1016/j.scog.2015.04.005. PMC 5779300. PMID 29379765.

- Giordano GM, Koenig T, Mucci A, Vignapiano A, Amodio A, Di Lorenzo G, et al. (2018). "Neurophysiological correlates of Avolition-apathy in schizophrenia: A resting-EEG microstates study". NeuroImage. Clinical. 20: 627–636. doi:10.1016/j.nicl.2018.08.031. PMC 6128100. PMID 30202724.

- Andreou C, Faber PL, Leicht G, Schoettle D, Polomac N, Hanganu-Opatz IL, et al. (February 2014). "Resting-state connectivity in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia: insights from EEG microstates". Schizophrenia Research. 152 (2–3): 513–20. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2013.12.008. PMID 24389056. S2CID 21444679.

- da Cruz JR, Favrod O, Roinishvili M, Chkonia E, Brand A, Mohr C, et al. (June 2020). "EEG microstates are a candidate endophenotype for schizophrenia". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3089. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16914-1. PMID 32555168. S2CID 219730748.

- Rieger K, Diaz Hernandez L, Baenninger A, Koenig T (2016). "15 Years of Microstate Research in Schizophrenia - Where Are We? A Meta-Analysis". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 7: 22. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00022. PMC 4767900. PMID 26955358.

- Cantero JL, Atienza M, Salas RM, Gómez CM (1999). "Brain spatial microstates of human spontaneous alpha activity in relaxed wakefulness, drowsiness period, and REM sleep". Brain Topography. 11 (4): 257–63. doi:10.1023/A:1022213302688. PMID 10449257. S2CID 13961921.