East German jokes

East German jokes, jibes popular in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR, also known as East Germany), reflected the concerns of East German citizens and residents between 1949 and 1990. Jokes frequently targeted political figures, such as Socialist Party General Secretary Erich Honecker or State Security Minister Erich Mielke, who headed the Stasi secret police.[1] Elements of daily life, such as economic scarcity, relations between the GDR and the Soviet Union or Cold War rival, the United States, were also common.[2] There were also ethnic jokes, highlighting differences of language or culture between Saxony and Central Germany.

Political jokes as a tool of protest

Hans Jörg Schmidt sees the political joke in the GDR as a tool to voice discontent and protest. East German jokes thus mostly address political, economic and social issues, criticise important politicians such as Ulbricht or Honecker, and political institutions or decisions. For this reason, Schmidt sees them as an indicator for popular opinion or as a “political barometer” that signals the opinion trends among the population.[3]

Sentences

According to Bodo Müller, an expert of East German jokes, no one was ever officially convicted due to a joke; the Stasi called it propaganda that was a threat to the state or anti-state agitation. Officially, it was seen as a violation of Paragraph 19 "State-endangering propaganda and hate speech". However, it was taken very seriously, with friends and neighbours being interrogated. The trials were mostly public and thus, the jokes were never read there. Of the 100 people in Bodo Müller’s research, 64 were convicted for one or more jokes. The sentence was usually between one and three years in prison. The harshest verdict was four years.[4]

Most of the sentences were handed down in the 1950s, before the Wall was built. After that, there was a rapid decline in sentences for joke-tellers, with the last verdict in 1972 against three engineers who had told jokes in the breakfast break. The Stasi continued to arrest joke-tellers, but convictions ceased. In the 1980s, reports of popular sentiment delivered by the Stasi to SED district councils on a monthly basis revealed more and more statements about political jokes recounted in company, union, and even party rallies.[5]

Operation GDR joke

In the Cold War times, the GDR was also one of the target areas of the West German Federal Intelligence Service. In the mid-1970s, someone in Pullach had the startling idea of intelligence gathering and evaluating political jokes about "over there". Thus, at the end of 1977, the BND in Pullach launched the secret operation "GDR joke", whereby BND agents had to collect and evaluate political jokes in the GDR.

Among other things, the staff interviewed refugees and displaced persons from the GDR in the emergency accommodation camps of the FRG. So-called "train investigators" - mostly middle-aged women - listened to their fellow passengers in seemingly harmless chats. Additionally, West German citizens, who received visitors from the GDR or were themselves on kinship visits in the east, were asked for jokes. Overall, the BND succeeded in discovering thousands of GDR jokes within 14 years. Of these, 657 reached the office of the Federal Chancellor on secret service routes.[6]

Examples

Country and politics

- Which three great nations in the world begin with "U"? — USA, USSR, and our GDR. (German: Was sind die drei großen Nationen der Welt, beginnend mit "U"? USA, UdSSR, und unsere DDR. This alludes to how official discourse often used the phrase "our GDR", and also often exaggerated the GDR's world status.)

- The United States, the Soviet Union and the GDR want to raise the Titanic. The United States wants the jewels presumed to be in the safe, the Soviets are after the state-of-the-art technology, and the GDR - the GDR wants the band that played as it went down.[7]

- A school teacher asks little Fritzie: "Fritzchen, why are you always speaking of our Soviet brothers? It's Soviet friends." — "Well, you can always choose your friends."

- Capitalism is the exploitation of man by man. What about Socialism? Under Socialism it is exactly the other way around. (German: Kapitalismus ist die Ausbeutung des Menschen durch den Menschen. Und wie ist es mit dem Sozialismus? Da ist es genau umgekehrt!)

- A trainee on his first day on his new job in a newspaper office. The news comes in over the wire that 'Sicily has drifted away from Italy and is now stranded on the English coast.' In the paper the next day, no mention is made of the event. Instead, the headline reads 'Harvest Saved'. 'Notice', the chief editor says to the astonished young man, 'our newspaper's task is not to inform our citizens, but to confuse the class enemy.'

- Why is toilet paper so rough in the GDR? In order to make every last asshole red.

Stasi

- How can you tell that the Stasi has bugged your apartment? — There's a new cabinet in it and a trailer with a generator in the street. (This is an allusion to the primitive state of East German microelectronics.)

- Honecker and Mielke are discussing their hobbies. Honecker: "I collect (German sammeln) all the jokes about me." Mielke: "Well we have almost the same hobby. I collect (German einsammeln, used figuratively like to garner) all those who tell jokes about you." (Compare with a similar Russian political joke.)

- Why do Stasi officers make such good taxi drivers? — You get in the car and they already know your name and where you live.

- Why do the Stasi work together in groups of three? — You need one who can read, one who can write, and a third to keep an eye on the two intellectuals.

Honecker

- Early in the morning, Honecker arrives at his office and opens his window. He greets the Sun, saying: "Good morning, dear Sun!" — "Good morning, dear Erich!" Honecker works, and then at noon he heads to the window and says: "Good day, dear Sun!" — "Good day, dear Erich!" In the evening, Erich calls it a day, and heads once more to the window, and says: "Good evening, dear Sun!" Hearing nothing, Honecker says again: "Good evening, dear Sun! What's the matter?" The sun retorts: "Kiss my arse. I'm in the West now!" (from the 2006 Oscar-winning movie The Lives of Others)

- What do you do when you get Honecker on the phone? Hang up and try again. (This is a pun with the German words aufhängen und neuwählen, meaning both "hang up the phone and dial again" and "hang him and vote again".)

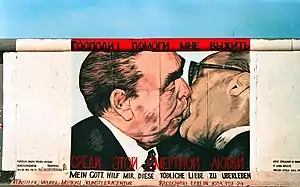

- Leonid Brezhnev is asked what his opinion of Honecker is: "Well, politically – I don't have much esteem for him. But – he definitely knows how to kiss!"

- A plane with Brezhnev, Carter and Honecker comes down to hell. The devil welcomes them and asks them which country they're from. Brezhnev: 'Soviet Union. We are the biggest country of the world.' Devil: 'I don't know. Off to the cauldron.' Carter: 'United States. We are the mightiest country of the world.' Devil: 'I don't know. Off to the cauldron.' Honecker: 'My country is very small. You won't know it: GDR.' Devil: 'Sure. Peace, Friendship, Solidarity. That's where our kettle is from.' (Allusion to the extensive exports in order to get hard currency.)

Economy

- When an East German retiree returns from his first trip to West Germany, his children ask him what it was like. He replies: 'Well, it's basically the same as here: you can get anything for West German marks.'

- What are the four deadly enemies of socialism? Spring, summer, autumn, winter.

- Two snowflakes in the sky: 'I'm heading to Sweden, to bring joy to the children.' - 'I'm going to the GDR, to bring down the economy.'

- What would happen if the desert became a socialist country? — Nothing for a while… then the sand becomes scarce.

- How can you use a banana as a compass? — Place a banana on the Berlin Wall. The bitten end would point East.

Trabant

- What's the best feature of a Trabant? — There's a heater at the back to keep your hands warm when you're pushing it.

- What does "601" stand for?" (in German, "601" is read as "six hundred and one")

- (original version) 600 people ordered cars, and only one has had it delivered.

- (variant from 1990) 600 cars on the dealership lot, and only one customer.

- (other variant) Space for 6 people, comfort for zero, and one to push it.

- How do you catch a Trabi? — Just stick chewing gum on the highway. (Allusion to the Trabant's underpowered motor.)

- What is the longest car on the market? — The Trabant, at 12 meters length. 2 meters of car, plus ten meters of smoke.

- A man driving a Trabant suddenly breaks his windshield wiper. Pulling into a service station, he hails a mechanic. 'Wipers for a Trabi?' he asks. The mechanic thinks about it for a few seconds and replies, 'Yes, sounds like a fair trade.' (Allusion to the shortage of spare parts for cars.)

- A new Trabi has been launched with two exhaust pipes — so you can use it as a wheelbarrow.[8]

- How do you double the value of a Trabant? — Fill it with gas.[9]

- A citizen orders a Trabant car. The salesman tells him to come back to pick it up in nine years. The customer asks: 'Am I to come back in the morning or in the evening then?' — 'You're joking, aren't you? What is the difference?' — 'Well sir, the plumber's coming in the morning.'

Saxons

- The doorbell rings. The woman of the house goes to the door and quickly returns, looking rather startled: "Dieter! There's a man outside who just asks, Tatü tata?" (Tatü tata is onomatopoeia for the sound of a police car siren). Dieter goes to the door and comes back laughing. "It's my colleague from Saxony, asking s do Dieto da?" (standard German Ist der Dieter da?, i.e. "Is Dieter there?", in Saxon dialect)

- A Saxon sits at a table in a cafe. Another man takes a seat and kicks him in the shin. He glances up briefly but says nothing. The man kicks him again. Now the Saxon says: 'If you do this for a third time, I will switch to another table.' (Allusion to the Saxon's mentality.)

See also

References

- Ben Lewis, Hammer and Tickle: A Cultural History of Communism, London: Pegasus, 2010

- Ben Lewis, "Hammer & tickle," Prospect Magazine, May 2006

- Schmidt, Hans Jörg. "Ulbricht klopft an die Himmelspforte...: Der politische Witz in der DDR als historisches Kondensat". Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte. 17 (2): 443–446.

- Bodo Mueller (2016). Lachen gegen die Ohnmacht: DDR-Witze im Visier der Stasi

- Locke, Stefan. "„Nie hieß es: War doch nur ein Witz"". Frankfurter Allgemeine. FAZ. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- "Kein Witz! DDR-Witze als Ziele des BND". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. MDR. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Funder, Anna (2015). Stasiland. Text Publishing. p. 237. ISBN 1877008915.

- Stoldt, Hans-Ulrich. "East German Jokes Collected by West German Spies". Spiegel Online. Spiegel. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- James, Kyle (19 May 2007). "Go, Trabi, Go! East Germany's Darling Car Turns 50". DW. DW. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

Further reading

- Ben Lewis, Hammer and Tickle: A Cultural History of Communism, London: Pegasus, 2010

- Ben Lewis, "Hammer & tickle," Prospect Magazine, May 2006

- de Wroblewsky, Clement; Jost, Michael (1986). Wo wir sind ist vorn: der politische Witz in der DDR oder die verschiedenen Feinheiten bzw. Grobheiten einer echten Volkskunst [Where we are is the Front: The Political Joke in the GDR or the Subtlety and Cruelty of Genuine Folk Art] (in German). Rasch und Röhring. ISBN 3-89136-093-2.

- Mueller, Bodo (2016). Lachen gegen die Ohnmacht: DDR-Witze im Visier der Stasi [Laughing against powerlessness: GDR jokes in the Stasi's sights] (in German). Christoph Links. ISBN 978-3861539148.

- Franke, Ingolf (2003). Das grosse DDR-Witz.de-Buch: vom Volk, für das Volk [The Big Book of Jokes from DDR-Witz.de: By the People, for the People] (in German). WEVOS. ISBN 3-937547-00-2.

- Franke, Ingolf (2003). Das zweite grosse DDR-Witze.de Buch [The Second Big Book of Jokes from DDR-Witz.de] (in German). WEVOS. ISBN 3-937547-01-0.

- Rodden, John (2002). Repainting the Little Red Schoolhouse: A History of Eastern German Education, 1945-1995. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511244-X.