Eastern European Jewry

The expression 'Eastern European Jewry' has two meanings. The first meaning refers to the current political spheres of the Eastern European countries and the second refers to the Jewish kibbutzim in Russia and Poland. The phrase 'Eastern European Jews' or 'Jews of the East' (from German: Ostjuden) was established during the 19th century in the German Empire and in the western provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, aiming to distinguish the integrating Jews in Central Europe from those in the East. This feature deals with the second meaning of the concept of Eastern European Jewry- the Jewish groups that lived in Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Russia, Romania, Hungary and modern Moldova in collective settlement (from Hebrew: Kibbutz- קיבוץ). Many of whom spoke Yiddish.

At the beginning of the 20th century, over 6 million Jews lived in Eastern Europe. They were organized in large and small communities, living in big cities such as Warsaw (with a population of about 300,000 Jews) and in small towns with only tens or hundreds of Jews.

From the beginning of the Jewish settlement to the 18th century

The first Jewish settlement in Eastern Europe began in a colony on the shores of the Black Sea during the 1st century. The settlement, which was located in the north of the Black Sea, was the only Jewish settlement in Eastern Europe until the 7th century. During that period, Jews began to immigrate to the east, towards the Khazar state. The immigrant Jews came from Byzantium and Islamic countries, and, like the Christians and Muslims, they received full religious and legal rights there. At the end of the 10th century, the Khazar state collapsed and the center of Jewish gravity in Eastern Europe moved to the Kiev principality. Kiev was the political and cultural center of the southern Russian duchies. The Jews played a significant role in the foreign trade of the city until the end of the 11th century and then, from the 12th century along with the rest of Central Europe.

The Jews of Kiev are the submitters and receivers of the transaction of messages found amongst in the Cairo Geniza.

During the end of the 12th century and the beginning of the 13th century, organized Jewish communities in Eastern Europe began to form. Their population growth stemmed mainly from large migrations from Central Europe. Even non-Ashkenazi Jews settled in Eastern Europe, but their number was relatively small, and their influence on the socio-cultural character of Jews in Eastern Europe was marginal.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the number of Jews in Eastern Europe was estimated at between 10,000 and 30,000. Some of their communities spoke Leshon Knaan and held various of other Non-Ashkenazi traditions and customs.[1] In parts of Eastern Europe, before the arrival of the Ashkenazi Jews from Central Europe, some non-Ashkenazi Jews were present who spoke Leshon Knaan and held various other non-Ashkenazi traditions and customs.[1] As early as the beginning of the 17th century, it was known that there were Jews living in cities of Lithuania who spoke "Russiany" (from Hebrew: רוסיתא) and did not know the "Ashkenaz tongue", i.e. German-Yiddish. In 1966, the historian Cecil Roth questioned the inclusion of all Yiddish speaking Jews as Ashkenazim in descent, suggesting that upon the arrival of Ashkenazi Jews from Central Europe to Eastern Europe, from the Middle Ages to the 16th century, there were already a substantial number of Jews there who later abandoned their original culture in favor of Ashkenazi culture.[2][3] However, according to more recent research, mass migrations of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews occurred to Eastern Europe from the west who increased due to high birth rates and absorbed and/or largely replaced the preceding non-Ashkenazi Jewish groups of Eastern Europe (the latter groups' numbers are estimated by demographer Sergio DellaPergola to have been small). In the mid-18th century, the number of Jews increased to about 750,000. During this period only one-third of East European Jews lived in areas with a predominantly Polish population. The rest of the Jews lived among other peoples, mainly in the Ukrainian and Russian-Lithuanian environments. The numerical increase was due to mass migration of Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazi Jews from Central Europe to Eastern Europe beginning from the Middle Ages to the 16th century, as well as a high birth rate among these immigrants.[4] Genetic evidence also indicates that Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews largely descended from Ashkenazi Jews who migrated from central Europe and subsequently experienced high birthrates and genetic isolation.[5]

In the mid-18th century, two-thirds of the Jewish population in Eastern Europe lived in cities or towns, and a third lived in villages - a unique phenomenon that hardly existed in Western Europe. In every village where Jews lived, there were only two Jewish families on average, and no more than ten Jews. In most of the urban localities in which they lived, the Jewish population was on average half the number of residents. It follows that in many towns there was a Jewish majority. This reality has been intensified over the years, with the percentage of Jews in cities and towns increasing, and thus the "shtetl" phenomenon was created - the "Jewish town", a large part of which was Jewish, and whose Jewish cultural character was prominent.

Economics and commerce

The Jews engaged in trade and various crafts, such as tailoring, weaving, leather processing and even agriculture. The economic activity of Eastern European Jewry was different from that of Central and Western European Jews: in Eastern Europe, the Jews developed specializations in trade, leasing, and crafts, which were hardly found in Western Europe. The Eastern European Jewry also had a great deal of involvement in economic matters that Jews in Central and Western Europe did not deal with at all.

Until the mid-17th century with the 1648 Cossack riots on Jewish population, eastern European Jews lived in a relatively comfortable environment that enabled them to thrive. The Jews, for the most part, enjoyed extensive economic, personal and religious freedom. Thus, for example, deportations, foreclosure of Jewish property, and the removal of financial debts of non-Jews to Jews, which were common in Western Europe, hardly existed in the East. Despite the privileges, there were also hatred expressions towards the Jews. This phenomenon was described by a Jewish sage named Shlomo Maimon:

"It is possible that there is no country other than Poland, where freedom of religion and hatred of religion are found in equal measure. The Jews are allowed to preserve their religion with absolute freedom, and the rest of the civil rights have been assigned to them, and they have even their own courts. And in opposite to that, you find that religion hatred is so great there to the extent of that matter, the word 'Jew' is an abomination."

Traditional life

The amount of Torah study among Eastern European Jews at the beginning of their settlement was little. As a result, many halakhic (from Hebrew: הלכתיות) questions and problems were addressed to rabbis and Torah scholars in Germany and Bohemia which were close to them. From the 16th century, luxurious study centers were established in Eastern Europe, where the Hassidic movement also began to develop.

Social Structure

The Jewish social structure in Eastern Europe was built of communities and from the mid-16th century to 1764, central institutions, including communal ones, of self-leadership in Eastern Europe were running. The two main institutions were the Four-State Committee and the Lithuanian State Council. The committees' role was to collect taxes from the Jewish communities and deliver them to the authorities. Later they took it upon themselves to represent the Jewish community to the foreign rulers of those countries. In addition, the committee had judicial authority over internal laws and Halachot (from Hebrew: הלכות) within the Jewish communities.

The Council of Four Lands was the highest institution among the committees. The committee was composed out of seven rabbinic judges when the head of them was always a representative of the Lublin community. The other members of the committee were representatives of the cities of Poznan, Krakow and Lvov. Historical documents bearing the Committee's signature indicate that in certain periods the committee was expanded to represent all the important communities in the kingdom, and then the number of representatives was close to thirty. At first, the committee met in Lublin, giving the city the status of a top-notch Jewish center. The conference, which lasted about two weeks, was held once a year during the winter, when the city's largest trade fair was coordinated. In a later period, the conference was held twice a year: a winter gathering in Lublin and a summer conference in the city of Yaroslav in Galicia.

From the late 18th century to the beginning of the 20th century

In the late 18th century, the Jews of Eastern Europe were divided into two major geographic regions: a settlement controlled by the Russian Empire, and a Galicia under the control of the Austria-Hungarian Empire.

The settlement

The three divisions of Poland (first in 1772, then in 1793, and finally in 1795) left the Aryan part of the Polish Jewry under the authority of the Russian Empire. The Russian government turned out to be less tolerant towards Jews, and more restrictions were imposed on Jews than the rest of the Polish people. In 1791 Czarina Yekaterina the Great established the region of the Settlement (the 'Moshav') in the western fringes of the empire, where only Jews were allowed to live. The Moshav included most of the former territories of Poland and Lithuania, which were populated by concentrations of Jews. Limiting those boundaries led to the uprooting and deportation of Moscow and St. Petersburg Jews to the eastern border of the country which was one of the main goals of the authorities). Later, the Jews of Kiev were also forbidden to live in their own city, even though Kiev itself was included in the "region of the Settlement."

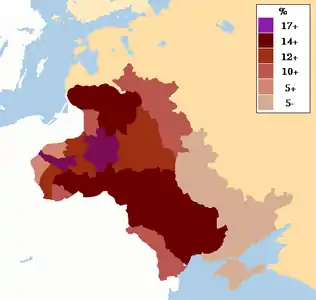

At the beginning of the 20th century, more than five million Jews lived in Czarist Russia, with 90% of them concentrated in the region of the Settlement and about three million Jews lived in the former borders of Poland. According to various estimates, Eastern European Jewry at the beginning of the 20th century constituted 80% of world Jewry.

Galicia

Another large Jewish community in Eastern Europe was Galicia, the territory that was given to Austria in the partition of Poland. Towards the end of the 19th century, Emperor Franz Joseph intended to "acculturate" the Jews by establishing a network of schools for general studies. Some Jews supported this goal, but most of them opposed it. Further resistance arose when an attempt was made to settle the Jews on the land.

The Jews in Galicia were known for their religious piety, and they fought hard against the Enlightenment and against attempts to "assimilate" them culturally. There was also a sharp confrontation between supporters of Hasidism and those opposed to it (Misnagdim). Eventually Hasidism won and became the dominant movement among the Jews of Galicia.

In 1867, the Jews of Galicia were granted full equality of rights, and thus were the first among the Jews of Eastern Europe to be emancipated. The Zionist movement flourished in Galicia. During the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, before World War I the Jewish community flourished in Galicia. A large number of books and poems were published there, many Torah sages were engaged in it and Zionism and Yiddish culture also emerged. At the beginning of the 20th century, the number of Jews in Galicia reached more than 800,000.

Antisemitism

Antisemitism in Switzerland in the years between the First and Second World Wars was mostly directed towards the so-called Ostjuden who were perceived as having foreign dress and culture. In fact, Ostjuden are explicitly mentioned by Heinrich Rothmund, the head of the Swiss federal Alien Police: "...we are not such horrible monsters after all. But that we do not let anyone walk all over us, and especially not Eastern Jews, who, as it is well known, try and try again to do just that, because they think a straight line is crooked, here our position is probably in complete agreement with our Swiss people."[6]

As antisemitism in Germany escalated following the First World War, feelings among German Jews were divided on the Yiddish-speaking Eastern European Jews. Some German Jews, wrestling with the notion of their own German identity, became more accepting of a shared identity with Eastern Jewry. Austrian novelist Joseph Roth depicted the misfortunes of Eastern European Jewry in the aftermath of the First World War in his novel The Wandering Jews. After the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935, Roth said the archetype of the "Wandering Jew" now extended to the German Jewish identity who he described as "more homeless than even his cousin in Lodz".[7]

See also

References

- Israel Bartal, "The Eastern European Jews Prior to the Arrival of the Ashkenazim", The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, May 29th, 2016.

- Cecil Roth, "The World History of the Jewish People. Vol. XI (11): The Dark Ages. Jews in Christian Europe 711-1096 [Second Series: Medieval Period. Vol. Two: The Dark Ages", Rutgers University Press, 1966. Pp. 302-303.

- Edgar C. Polomé, Werner Winter, Reconstructing Languages and Cultures, Walter de Gruyter, 2011-06-24, ISBN 978-3-11-086792-3.

- Sergio DellaPergola, Some Fundamentals of Jewish Demographic History, in "Papers in Jewish Demography 1997", Jerusalem, The Hebrew University, 2001.

- Gladstein AL, Hammer MF (March 2019). "Substructured population growth in the Ashkenazi Jews inferred with Approximate Bayesian Computation". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (6): 1162–1171. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz047.

- Wallace, Max (2018). In the Name of Humanity. New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-5107-3497-5.

- "The End of German-Jewish Life: Ostjuden as a Metaphor for All Jews". The University of Chicago Library.

Sources

- Jared Diamond (1993). "Who are the Jews?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-21. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- Hammer, MF; Redd, AJ; Wood, ET; et al. (June 2000). "Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97: 6769–6774. doi:10.1073/pnas.100115997. PMC 18733. PMID 10801975. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- Wade, Nicholas (9 May 2000). "Y Chromosome Bears Witness to Story of the Jewish Diaspora". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- "Germany: Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2013-07-19.

- Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopaedia 2007. Europe. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2007.