Eastern South Slavic

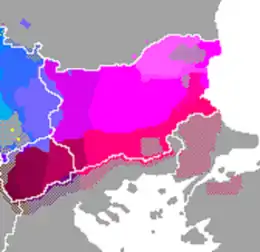

The Eastern South Slavic dialects form the eastern subgroup of the South Slavic languages. They are spoken mostly in Bulgaria, North Macedonia and adjacent areas in the neighbouring countries. They form the so-called Balkan Slavic linguistic area which encompasses the southeastern part of the dialect continuum of South Slavic.

| Eastern South Slavic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Central and Eastern Balkans |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | east2269 |

Linguistic features

Languages and dialects

Eastern South Slavic dialects share a number of characteristics that set them apart from the other branch of the South Slavic languages, the Western South Slavic languages. This area consists of the Bulgarian and the Macedonian languages and per some authors encompasses the southeastern dialect of the Serbian language, the so-called Prizren-Timok dialect.[1] The last is part of the broader transitional Torlakian dialectal area. The Balkan Slavic area is also part of the Balkan Sprachbund. The external boundaries of the Balkan Slavic/Eastern South Slavic area can be defined with the help of some linguistic structural features. Among the most important of them are: the loss of the infinitive and case declension, and the use of enclitics definite articles.[2] In the Balkan Slavic languages, clitic doubling also occurs, which is characteristic feature of all the languages of the Balkan Sprachbund.[3] The grammar of Balkan Slavic looks like a hybrid of “Slavic” and “Romance” grammars with some Albanian additions.[4] The Serbo-Croatian vocabulary in both Macedonian and Serbian-Torlakian is very similar, stemming from the border changes of 1878, 1913, and 1918, when these areas came under direct Serbian linguistic influence.

Areal

The external and internal boundaries of the linguistic sub-group between the transitional Torlakian dialect and Serbian and between Macedonian and Bulgarian languages are not clearly defined. For example, standard Serbian, which is based on its Western (Eastern Herzegovinian dialect), is very different from its Eastern (Prizren-Timok dialect), especially in its position in the Balkan Sprachbund.[5] As a whole, Torlakian is closer to Macedonian than to Serbian and falls into the Macedonian-Bulgarian diasystem.[6] However, this division is a matter of contention among linguists, and further research and linguistic consensus is needed to make a final conclusion. During the 19th century, the Balkan Slavic dialects were often described as forming the Bulgarian language.[7] At the time, the areas east of Niš were considered under direct Bulgarian ethnolinguistic influence and in the middle of the 19th Century, that motivated the Serb linguistic reformer Vuk Karadžić to use the Eastern Herzegovina dialects for his standardisation of Serbian.[8] Bulgarian was standardized afterwards, at the end of the 19th century on the basis of its eastern Central Balkan dialect, while Macedonian was standardized in the middle of the 20th century using its west-central Prilep-Bitola dialect. Although some researchers still describe the standard Macedonian and Bulgarian languages as varieties of a pluricentric language, they have very different and remote dialectal bases.[9] Jouko Lindstedt has assumed that the dividing line between Macedonian and Bulgarian maybe in fact the Yat border,[10] which goes through the modern region of Macedonia along the Velingrad - Petrich - Thessaloniki line.[11] Many older Serbian scholars on the other hand believed that the Yat border divides the Serbian and Bulgarian languages.[12] However, modern Serbian linguists such as Pavle Ivic have accepted that the main isoglosses bundle dividing Eastern and Western South Slavic runs from the mouth of the Timok river alongside Osogovo mountain and Sar Mountain.[13] In Bulgaria the Yat border is considered the most important Bulgarian isogloss.

History

Some of the phenomena that distinguish western and eastern subgroups of the South Slavic people and languages can be explained by two separate migratory waves of different Slavic tribal groups of the future South Slavs via two routes: the west and east of the Carpathian Mountains.[14] The western Balkans was settled with Sclaveni, the eastern with Antes.[15] Haplogroup R1a, the major haplogroup among Slavic tribes, reveals that the haplogroup of the Serbo-Croat group is mainly constituted by R1a-L1280 or R1a-CTS3402, while the Macedono-Bulgarian is more associated with of the R1a-L1029. The early habitat of the Slavic tribes, that are said to have moved to Bulgaria, was described as being in present Ukraine and Belarus. The mythical homeland of the Serbs and Croats lies in the area of today Bohemia, in the present-day Czech Republic and in Lesser Poland. In this way, the Balkans were settled by different groups of Slavs from different dialect areas. This is evidenced by some isoglosses of ancient origin, dividing the western and eastern parts of the southern Slavic range.

The extinct Old Church Slavonic which survives in a relatively small body of manuscripts, most of them written in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 10th century is also classified as Eastern South Slavic. The language has an Eastern Southern Slavic basis with small admixture of Western Slavic features, inherited during the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius to Great Moravia during the 9th century.[16] New Church Slavonic represents a later stage of the Old Church Slavonic, and is its continuation through the liturgical tradition introduced by its precursor. Ivo Banac maintains that during the Middle Ages, Torlak and Eastern Herzegovinian dialects were Eastern South Slavic, but since the 12th century, the Shtokavian dialects, including Eastern Herzegovinian, began to separate themselves from the other neighboring Eastern dialects, counting also Torlakian.[17]

The specific contact mechanism in the Balkan Sprachbund, based on the high number of second Balkan language speakers there, is among the key factors that reduced the number of Slavic morphological categories in that linguistic area.[18] The Russian Primary Chronicle, written ca. 1100, claims that then the Vlachs attacked the Slavs on the Danube and settled among them. Nearly at the same time are dated the first historical records about the emerging Albanians, as living in the area to the west of the Lake Ohrid. There are references in some Byzantine documents from that period to "Bulgaro-Albano-Vlachs" and even to "Serbo-Albano-Bulgaro-Vlachs".[19] As a consequence, case inflection, and some other characteristics of Slavic languages, were lost in Eastern South Slavic area, approximately between the 11th-16th centuries. Migratory waves were particularly strong in the 16th–19th century, bringing about large-scale linguistic and ethnic changes on the Central and Eastern Balkan South Slavic area. They reduced the number of Slavic-speakers and led to the additional settlement of Albanian and Vlach-speakers there.

See also

References

- Victor Friedman, The Typology of Balkan Evidentiality and Areal Linguistics; Olga Mieska Tomic, Aida Martinovic-Zic as ed. Balkan Syntax and Semantics; vol. 67 от Linguistik Aktuell/Linguistics Today Series; John Benjamins Publishing, 2004; ISBN 158811502X; p. 123.

- Jouko Lindstedt, Conflicting Nationalist Discourses in the Balkan Slavic Language Area in The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders with editors: Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi and Catherine Gibson; Palgrave Macmillan; 2016; ISBN 978-1-137-34838-8; pp. 429-447.

- Olga Miseska Tomic, Variation in Clitic-doubling in South Slavic in Article in Syntax and Semantics 36: 443-468; January 2008; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9781848550216_018 .

- Jouko Lindstedt, Balkan Slavic and Balkan Romance: from congruence to convergence in Besters-Dilger, Juliane & al. (eds.). 2014. Congruence in Contact-induced Language Change. Berlin - Boston: De Gruyter. ISBN 3110373017; pp. 168–183.

- Motoki Nomachi, “East” and “West” as Seen in the Structure of Serbian: Language Contact and Its Consequences; p. 34. in Slavic Eurasian Studies edited by Ljudmila Popović and Motoki Nomachi; 2015, No.28.

- Robert Lindsay, Mutual Intelligibility of Languages in the Slavic Family in Last Voices/Son Sesler; 2016 DOI: https://www.academia.edu/4080349/Mutual_Intelligibility_of_Languages_in_the_Slavic_Family .

- Friedman V A (2006), Balkans as a Linguistic Area. In: Keith Brown, (Editor-in Chief) Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics, Second Edition, volume 1, pp. 657-672. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Drezov, Kyril (1999). "Macedonian identity: An overview of the major claims". In Pettifer, James (ed.). The New Macedonian Question. MacMillan Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780230535794.

- Ammon, Ulrich; de Gruyter, Walter (2005). Sociolinguistics: an international handbook of the science of language and society. p. 154. ISBN 3-11-017148-1. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi, Catherine Gibson as ed., The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, Springer, 2016; ISBN 1137348399, p. 436.

- Енциклопедия „Пирински край“, том II. Благоевград, Редакция „Енциклопедия“, 1999. ISBN 954-90006-2-1. с. 459.

- Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley, The Slavic Languages, Cambridge Language Surveys, Cambridge University Press, 2006; ISBN 1139457284, p. 510.

- Ivic, Pavle, Balkan Slavic Migrations in the Light of South Slavic Dialectology in Aspects of the Balkans. Continuity and change with H. Birnbaum and S. Vryonis (eds.) Walter de Gruyter, 2018; ISBN 311088593X, pp. 66-86.

- The Slavic Languages, Roland Sussex, Paul Cubberley, Publisher Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 1139457284, p. 42.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 1-4039-6417-3

- Lunt, Horace G. (2001). Old Church Slavonic Grammar (7th ed.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; p.1; ISBN 978-3-110-16284-4.

- Ivo Banac, The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics, Cornell University Press, 1988, ISBN 0801494931, p. 47.

- Wahlström, Max. 2015. The loss of case inflection in Bulgarian and Macedonian (Slavica Helsingiensia 47); University of Helsinki, ISBN 9789515111852.

- John Van Antwerp Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0472082604, p. 355.