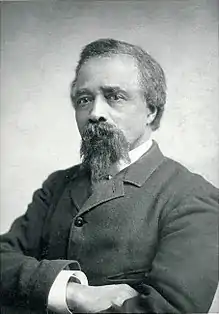

Edward Mitchell Bannister

Edward Mitchell Bannister (November 2, 1828 – January 9, 1901) was a Tonalist painter. Born in Canada, he spent his adult life in New England, where he was a prominent member of the African American cultural and political communities. He was a member of Boston's abolition movement and a founding member of the Providence Art Club.

Edward Mitchell Bannister | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | November 2, 1828 Saint Andrews, New Brunswick, Canada |

| Died | January 9, 1901 (aged 72) Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Resting place | North Burial Ground |

| Nationality | Canadian, American |

| Other names | Edwin, Ned |

| Education | Lowell Institute |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Tonalism |

| Spouse(s) | Christiana Carteaux Bannister |

Like other Tonalists, Bannister's style and predominantly pastoral subject matter were drawn from his admiration for the French artist Jean-François Millet and the French Barbizon School, while he also looked to the Rhode Island seaside for inspiration. He was a continual experimenter in artistic practice, and his artwork is noted for its connection to Idealist philosophies and his masterful control of color and atmosphere. He began his professional practice as a photographer and portraitist before eventually developing his signature landscape style.

Biography

Early life

Bannister was born on November 2, 1828, in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, near the St. Croix River, to Barbadian parents. His father Edward Bannister died in 1832, so Edward and his younger brother William were raised by their mother, Hannah Alexander Bannister.[1] Early on, Bannister was apprenticed to a cobbler, but his drawing skill was already noted among his friends and family.[2]:67 Bannister credited his mother with igniting his early interest in art. She died in 1844, after which Bannister and his brother lived on the farm of the wealthy merchant Harris Hatch.[3] There, he practiced drawing by studying and reproducing two Hatch family portraits, as well as studying the family library and Bible.[4]:12-13

Bannister and his brother found work aboard ships as mates and cooks and immigrated to the US.[3] They moved to Boston sometime in the late 1840s.[5][6] In the 1850 US census, they are listed as living at the same boarding house, with the Revaleon family, and working as barbers.[7]

Bannister had aspirations of painting but had difficulty finding an apprenticeship or academic programs that would accept him, likely due to racial prejudice. He would later express his frustration with being blocked out of artistic education: "Whatever may be my success as an artist is due more to inherited potential than to instruction" and "All I would do I cannot ... simply for the want of proper training."[2] He received his first oil painting commission, The Ship Outward Bound, in 1854 from an African American doctor, John V. DeGrasse.[1] Bannister's colleague, Jacob R. Andrews, created the commission's gilt frame.[2]:67

Boston student, artist, and activist

Bannister met Christiana Carteaux in 1853 when he applied to be a barber in her salon. They married on June 10, 1857; both were members of Boston's abolitionist movement.[5] Fellow abolitionist William Wells Brown described Bannister as "spare-made and slim, with an interesting cast of countenance, quick in his walk and easy in his manners."[8]:98 The couple boarded for two years with Lewis Hayden and Harriet Bell Hayden at 66 Southac Street, a stop on Boston's Underground Railroad (a support network for escaped slaves).[9]

In 1855, William Cooper Nell acknowledged Bannister's rising artistic status in his book The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution for his The Ship Outward Bound. By 1858, Bannister was listed as an artist in Boston's city directory. Around 1862, he spent a year training in photography in New York, likely to find better work to support his painting practice, after which he did work as a photographer, taking solar plates and tint photos. Bannister's earliest commissioned portrait was of Prudence Nelson Bell in 1864, which is around when he found studio space at the Studio Building in Boston.

Bannister was part of Boston's African American artistic community, which included Edmonia Lewis, William H. Simpson, and Nelson A. Primus.[1] He sang and acted as a member of both the Crispus Attucks Choir, which performed anti-slavery songs at public events, and The Histrionic Club, as well as serving as a delegate for the New England Colored Citizens Conventions in August 1859 and 1865. His name appears on petitions published in Boston's abolitionist newspaper The Liberator.

Bannister and Carteaux were devout members of the abolitionist Twelfth Baptist Church, located on Southac Street near their home at the Hayden House. In May 1859, Bannister served as the secretary for the church's meetings to respond to the Oberlin–Wellington Rescue of imprisoned fugitive slaves[10] and, in 1863, to plan celebrations for the Emancipation Proclamation.[11]

During the US Civil War, Carteaux lobbied for equal pay for African American soldiers and organized the 1864 soldiers’ relief fair for the Massachusetts 54th infantry regiment, 55th infantry regiment, and 5th cavalry regiment, which had gone without pay for over a year and a half.[8] Bannister donated his full-length portrait of Robert Gould Shaw, the commander of the 54th killed in action, to raise money for the cause.

The Bannister portrait of Robert Gould Shaw was one of several reclamations of Gould Shaw by members of Boston's African American artistic community such as Edmonia Lewis, despite Gould Shaw's Boston Brahmin background. It was displayed with the label "Our Martyr". The portrait was praised in the New York Weekly Anglo-African as "a fine specimen of art" and inspired a poem by Martha Perry Lowe entitled The Picture of Col. Shaw in Boston.[8]:99-100 The painting was purchased by the state of Massachusetts and installed in its state house, but its current location is unknown.[12]

Bannister's activism also took other forms: on June 17, 1865, Bannister marshaled around 200 members of the Twelfth Baptist Sunday School at a Grand Temperance Celebration on Boston Common. They marched under a banner reading "Equal rights for all men".[13]

Bannister eventually studied at the Lowell Institute with the artist William Rimmer for about a year.[14] Because of his daytime photography business, he mostly took his drawing classes at night. Through Rimmer and the community at the Studio Building, Bannister was inspired by the Barbizon school-influenced paintings of William Morris Hunt, who had studied in Europe and held numerous public exhibitions in Boston around the 1860s. He also formed a temporary painting partnership with Asa R. Lewis that lasted from 1868 to 1869. During that partnership of "Bannister & Lewis", Bannister began to advertise himself as both a portrait and landscape painter.[2]:27

Despite his early commissions, Bannister still struggled to receive recognition for his work due to racism in the US. An 1867 article in the New York Herald apparently belittled both him and his work, stating, "the negro has an appreciation for art while being manifestly unable to produce it".[14] The article reportedly spurred his desire to achieve success as an artist.[15]

Artistic success in Providence

Supported by Carteaux, Bannister became a full-time painter from 1870 on, shortly after they moved to Providence, Rhode Island, at the end of 1869.[5] He first took a studio in the Mercantile National Bank Building and eventually moved his studio to the Woods Building in Providence, where he shared a floor with artists like Sydney Burleigh and became friends with Providence painter George William Whitaker. Over time, he was drawn to paint more landscape; he received an 1872 award at the Rhode Island Industrial Exposition for Summer Afternoon and began submitting paintings to the Boston Art Club.[2]:29

Bannister finally received national commendation for his artistic skill when he won first prize for his large oil Under the Oaks at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial.[14][16] Bannister described the event to Whitaker:

I learned from the newspapers that '54' had received a first prize medal, so I hurried to the Committee Rooms to make sure the report was true. [...] As I jostled among them many resented my presence, some actually commenting within my hearing in a most petulant manner, what is that colored person in here for? [...] I endeavored to gain the attention of the official in charge. He was very insolent. Without raising his eyes, he demanded in the most exasperating tone of voice, 'Well what do you want here any way? Speak lively.' 'I want to enquire concerning 54. Is it a prize winner?' 'What's that to you,' said he? [sic] In an instant my blood was up: the looks that passed between him and others in the room were unmistakable. I was not an artist to them, simply an inquisitive colored man; controlling myself, I said deliberately, 'I am interested in the report that Under the Oaks has received a prize; I painted the picture.' An explosion could not have made a more marked impression. Without hesitation he apologized and soon every one in the room was bowing and scraping to me.[2]:29,34

— Edward M. Bannister

Even then, some jurors tried to rescind his award until the other exhibition artists protested.[17] Afterwards, Bannister reflected: "I was and am proud to know that the jury of award did not know anything about me, my antecedents, color or race. There was no sentimental sympathy leading to the award of the medal."[2]

As his career matured, Bannister received more commissions and accumulated many honors, several from the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Association (silver medals in 1881 and 1884).[1] Collectors and local notables Isaac Comstock Bates and Joseph Ely were among his patrons.[2]:45

He was an original board member of the Rhode Island School of Design in 1878. In 1880, Bannister joined with other professional artists, amateurs, and art collectors to found the Providence Art Club to stimulate the appreciation of art in the community. Their first meeting was in Bannister's studio in the Woods Building at the bottom of College Hill. He was the second to sign the club's charter, served on its initial executive board, and taught regular Saturday art classes.[18] He continued to show paintings at Boston Art Club exhibitions, as well as in Connecticut and at New York's National Academy of Design, and exhibited A New England Hillside at the New Orleans Cotton Exposition in 1885.[2]:45

In the 1880s, Bannister bought a small sloop, the Fanchon, and he would spend his summers sketching, painting watercolors, and sailing Narragansett Bay and up to Bar Harbor in Maine. He would return with his studies and use them as the basis for winter commissions. He supplemented his sailing trips with journeys to exhibitions in New York, but a planned trip to Europe fell through due to funding problems.

In 1885, with other art club members, Bannister helped found the "Anne Eliza Club" (or "A&E Club")—a communal discussion group whose members shared art and literature.[4]:20 Through his teaching there and at the Providence Art Club, he became a mentor to younger Providence artists, like Charles Walter Stetson: "Stetson mentions Bannister frequently in his diaries, claiming that 'He is my only confidant in Art matters & I am his.'"[2] Rhode Island engineer George Henry Corliss commissioned a painting from him in 1886, as Bannister's reputation grew.[2]:72

Bannister and Carteaux were consistent members of the African American community in Providence. They lived for a time in the boarding house of Ransom Parker, who had participated in the Dorr Rebellion,[19]:113 and were friends with merchant George Henry, Reverend Mahlon Van Horne, Brown graduate John Hope, and abolitionist George T. Downing, an ally from the Bannisters' political work in Boston.[2]:27 Carteaux founded the Home for Aged Colored Women, which is known as the Bannister Center today. Edward exhibited his painting Christ Healing the Sick in the home in 1892 and donated his portrait of Carteaux to it as well.[19]:117 Bannister's abolitionism likely led to conflict with the mostly white members of the Providence Art Club, which exhibited art with minstrel stereotypes in 1887 and 1893.[2]:49

Sometime around 1890, Bannister sold the Fanchon to Judge George Newman Bliss.[2]:75 Later in the 1890s, Bannister seems to have sold fewer paintings, perhaps due to waning popularity, and exhibited less often. In 1898, Bannister closed his studio and the couple moved to Boston for a year before returning to a smaller home in Providence on Wilson Street in 1900.[2]:53

Death

Bannister died of a heart attack on January 9, 1901, while attending an evening prayer meeting at his church, Elmwood Avenue Free Baptist Church. He had experienced heart trouble for some time but had completed two paintings only the previous day. During the service, he offered a prayer and shortly after sat down, gasping. His last words were reportedly "Jesus, help me."[2]:53

After his death, the Providence Art Club held a memorial exhibition in his name. In the exhibition pamphlet, they wrote:

His gentle disposition, his urbanity of manner, and his generous appreciation of the work of others, made him a welcome guest in all artistic circles. ... He painted with profound feeling, not for pecuniary results, but to leave upon the canvas his impression of natural scenery, and to express his delight in the wondrous beauty of land and sea and sky.[20]

He is buried in the North Burial Ground in Providence, under a stone monument designed by his art club friends.[21] The disparity between Bannister's financial difficulties at the end of his life and the support shown by Providence's artists after his death led one friend to say this about the memorial:

In the labor incident to this work I was constantly reminded of the remark attributed to the mother of Robert Burns on being shown the splendid monument erected to the memory of her gifted son: "He asked for bread and they gave him a stone."[19]:118

Carteaux was admitted to her Home for Aged Colored Women in 1902 and died in 1903 in a mental institution. She and Bannister are buried together.

Artistic style

Bannister is primarily known for his idealized landscapes and seascapes, but he also executed portraits, as well as biblical, mythological, and genre scenes later on. He advertised himself as a portraitist as a young painter, but eventually became popular for his landscapes.[2]:25 An intellectual autodidact, his tastes in literature were typical of an educated Victorian painter, including Spenser, Virgil, Ruskin, and Tennyson, from whose works much of his iconography can be traced. His work reflected the composition, mood, and influences of French Barbizon painters Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny. Defending Millet in The Artist and His Critics, Bannister saw him as the "profoundest, most ... spiritual artist of our time" who voiced "the sad, uncomplaining life he saw about him — and with which he sympathized so deeply."[2]

Historian Joseph Skerrett has noted the influence of the Hudson River School on Bannister, while maintaining that he consistently experimented throughout his career: "Bannister managed to please a conservative New England taste in art while continuing to try new methods and styles."[15] For their mutual affinity with the Hudson River School, Bannister has been compared to his contemporary, the Ohio-based African American painter Robert S. Duncanson.[22] Unlike the Hudson River School style, Bannister did not create meticulous landscapes but paid more attention to creating "generalized masses defined by light and shadow" and works that were more picturesque than sublime.[4]:28,32

In preparing a painting, Bannister would often make pencil or pastel studies in preparation for larger oil paintings.[2] Several of his compositions use classical, mathematical methods like the Golden Ratio or "Harmonic Grid" and make careful use of symmetry and asymmetry. In other paintings, his contrast of darks and lights create dynamic diagonals or circles that divide his work.[2]:13

Bannister's paintings are known for their delicate use of color to depict shadow and atmosphere and their loose brushwork. His later palette exhibited brighter, but more muted colors: the Boston Common scene he painted late in his life is a notable example.[23] This change in style stands in contrast to his earlier stated disapproval of Impressionist painting.[2]:53

Art historian Traci Lee Costa has argued that a "reductive" emphasis on Bannister's biography has taken attention away from "critical interpretation" of his artwork.[4] In the lecture The Artist and His Critics given to the Ann Eliza Club on April 15, 1886, and published afterward, Bannister spelled out his belief that making art is a highly spiritual practice—the pinnacle of human achievement. This lecture and its Idealistic view are linked to Bannister's Approaching Storm, which he completed in the same year. Approaching Storm features a human figure at its center, which is nonetheless rendered small by the surrounding landscape. Despite the implied drama, Bannister used a cool color palette of blues and greens, with contrasting yellows that provide warmth against the darker, almost purple sky.[4]:70-71 In its nearly religious approach and focus on subjective representations of nature, Bannister's philosophy has been compared to both German Idealism and American Transcendentalism. In his lecture The Artist and His Critics, Bannister made explicit reference to the works of Transcendentalist Washington Allston. Bannister's friend George W. Whitaker even referred to him as "The Idealist" in a 1914 article "Reminiscences of Providence Artists."[4]:55, 81

Although committed to freedom and equal rights for African Americans,[6] Bannister did not often directly represent those issues in his paintings. In one work, Hay Gatherers, Bannister depicts African American field laborers that combines his rural landscapes with a representation of the racial oppression and labor exploitation that marked Rhode Island, particularly in South County, where most of the state's plantations once were.[4]:73[2]:13 The geometric composition of the painting, which divides the figures and the landscapes into triangular sections, demonstrates how Bannister combined his seemingly idealized landscapes with his early political practice, which is visible in his humanist portraits such as Newspaper Boy.[24] One of Bannister's first commissions, The Ship Outward Bound, might have been a veiled allusion to the forced return of Anthony Burns to slavery and Virginia under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 in 1854.[25] On the other hand, Bannister has been criticized for not representing African American life in America: most of his works consisted of commissioned landscapes and portraits that reinforced European ideas.[26]

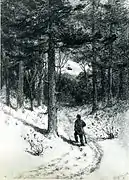

Another Bannister work with buried meaning is his 1885 drawing The Woodsman, which is thought to be Bannister's response to the murder of Amasa Sprague, an event that spurred the abolition of capital punishment in Rhode Island after the dubious conviction and hanging of John Gordon.[2]:13

Legacy

Bannister was the only major African American artist of the late nineteenth century who developed his talents without European exposure; and he was well known in the artistic community of Providence and admired within the wider East Coast art world. After his death, Bannister was largely forgotten by art history for almost a century for various reasons, principally racial prejudice. Still, he and his paintings are an indelible part of a refigured relationship between African American culture and the landscapes of Reconstruction-era America.[27]

Following the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Bannister's work was again celebrated and collected. In collaboration with the Rhode Island School of Design and the Frederick Douglass Institute, the National Museum of African Art held an exhibition titled Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1828–1901: Providence Artist.[28][4]:9 The Rhode Island Heritage Hall of Fame inducted Bannister in 1976, and, in 1978, Rhode Island College dedicated its Art Gallery in Bannister's name with the exhibition: Four From Providence: Alston, Bannister, Jennings & Prophet.[29]

The New York-based Kenkebala Gallery held two exhibitions of Bannister's work, one in 1992 curated by Corrinne Jennings in collaboration with the Whitney and one in 2001 on the centennial of Bannister's death.[30] From June 9 to October 8, 2018, the Gilbert Stuart Museum held an exhibition honoring Bannister and Carteaux's relationship, "My Greatest Successes Have Come Through Her": The Artistic Partnership of Edward and Christiana Bannister, as part of its Rhode Island Masters exhibition series.[31] Bannister's portrait of Christiana Carteaux was the center of the exhibition.

In September 2017, a Providence City Council committee unanimously voted to rename Magee Street (which had been named after a Rhode Island slave trader) to Bannister Street, in honor of Edward and Christiana Bannister.[32]

The historian Anne Louise Avery is currently compiling the first catalogue raisonné and a major biography of Bannister's work.[33]

House

In 1884, Bannister and Carteaux moved from the boarding house of Ransom Parker to 93 Benevolent Street, and lived there until 1899.[19] The two-and-a-half-story wooden house was built in c. 1854 by engineer Charles E. Paine and is now known as "The Vault" or "The Bannister House."[34] Euchlin Reeves and Louise Herreshoff purchased the house in the late 1930s and renovated it to add a brick exterior.[25] The renovation was made to create consistency with their next-door property, so both houses could hold their "little museum" of antiques. (Herreshoff died in 1967 and the extensive porcelain collection filling the Bannister House was donated to Washington and Lee University.[35])

Brown University bought the property in 1989 and used it to store refrigerators.[25] Due to a lack of plans for its preservation and use, the Providence Preservation Society put the Bannister House on its 2001 list of most endangered buildings in Providence,[34] and the house is listed as contributing to College Hill's historical designation. Brown University president Ruth Simmons assured historian and former Rhode Island deputy secretary of state Ray Rickman that the house would be preserved,[36] although the university debated whether to sell the house to a third party.[34]

Because its disrepair and long disuse made the house unsuitable for residence, Brown renovated the property in 2015 and restored it to its original appearance.[37] It was sold to Professor Jeff Huang in 2016 as part of the Brown to Brown Home Ownership Program—the program specifies that if the house is ever sold, it has to be sold back to the university.

Notable works

- The Newsboy [Boston Newsboy] [Newspaper Boy] (1869; Oil; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.)[38]

- Under the Oaks (1876; Oil; Unknown)

- River Scene (1883; Oil on canvas; Honolulu Museum of Art)

- Sabin Point, Narragansett Bay (1885; Oil on canvas; Gardner House, Providence, Rhode Island)

- Palmer River (1885; Oil on canvas; Private Collection)

- The Farm Landing (1892; Oil on canvas; King Gallery of Fine Art)

- Moon Over Harbor (1868; Oil on fiberboard; Smithsonian American Art Museum)

- Last Light (1890s; Oil on wood panel; Baltimore Museum of Art)

Selected artworks

Newspaper Boy, 1869, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Newspaper Boy, 1869, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum Governor Sprague's White Horse, 1869, oil on canvas, Rhode Island Historical Society

Governor Sprague's White Horse, 1869, oil on canvas, Rhode Island Historical Society Driving Home the Cows, 1881, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Driving Home the Cows, 1881, Smithsonian American Art Museum River Scene, 1883, oil on canvas, Honolulu Museum of Art

River Scene, 1883, oil on canvas, Honolulu Museum of Art Palmer River, 1885, oil on canvas, private collection[39]

Palmer River, 1885, oil on canvas, private collection[39] The Woodsman, 1885, graphite, Providence Art Club

The Woodsman, 1885, graphite, Providence Art Club Untitled, ca. 1885, Brooklyn Museum

Untitled, ca. 1885, Brooklyn Museum Neutakonanut, 1891, watercolor, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Neutakonanut, 1891, watercolor, Smithsonian American Art Museum

References

- "Edward Mitchell Bannister | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Holland, Juanita Marie; Jennings, Corrine (1992). Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1828-1901. New York: Kenkeleba House. ISBN 0874270839. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Holland, Juanita Marie; Jennings, Corrine (1992). Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1828-1901. New York: Kenkeleba House. p. 17. ISBN 0874270839.

- Lee Costa, Traci (February 2017). Edward Mitchell Bannister and the Aesthetics of Idealism (MA). Roger Williams University.

- "Edward M. Bannister biography". www.edwardbannister.com. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "African Americans in the Visual Arts: A Historical Perspective". 30 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-08-30. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Edward Bannister: United States Census, 1850". Family Search. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- Richardson, Marilyn (2009). "Taken From Life: Edward M. Bannister, Edmonia Lewis, and the Memorialization of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment". Hope & glory : essays on the legacy of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. Amherst. pp. 94–115. ISBN 9781558497221. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Davis, Paul. "5 Rhode Islanders who laid the groundwork for later activists". providencejournal.com. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Oberlin Rescuers: Meeting of Colored Citizens of Boston". www.digitalcommonwealth.org. The Liberator. June 10, 1859. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Emancipation Day". www.digitalcommonwealth.org. The Liberator. 25 December 1863. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Kresser, Katie Mullis (September 2006). "Power and Glory: Brahmin Identity and the Shaw Memorial". American Art. 20 (3): 32–57. doi:10.1086/511094. S2CID 160840665.

- "The Seventeenth June". Boston Post. 19 June 1865. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- Perry, Regenia A. (1976). Selections of Nineteenth-Century Afro-American Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 13–14.

- The headline and exact dating of the New York Herald article is unknown, but this story is often repeated in sources. Because sources do not provide a specific citation, it is possible the article did not exist and that this story is apocryphal. Skerrett, Joseph T. (1978). "Edward M. Bannister, Afro-American Painter (1828-1901)". Negro History Bulletin. 41 (3): 829. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44213838.

- The location of Under the Oaks is unknown. It was sold to a "Mr. Duffe" of Boston for $1500. Perry 1976, 13–14. It was described by a Professor J. P. Sampson "a four by six feet picture, representing in the foreground, a herd of sheep along the [stream] while further in the back-ground is a beautiful ascent, with a cluster of oaks, wide spread in their branches, like a great shed; and beneath this shelter can be seen numerous cows and sheep taking shelter from the storm." Holland 1992.

- "Newport, 1890–91". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Miner, George Leland; Chesley Worthington, W; Atwood, Louis D. Providence Art Club, 1880-2005. Providence Art Club. pp. 127, 132.

- Lancaster, Jane (November 2001). "'I Would Have Made Out Very Poorly Had It Not Been for Her': The Life and Work of Christiana Bannister, Hair Doctress and Philanthropist". Rhode Island History Journal. 59: 103–122.

- Edward Mitchel Bannister : memorial exhibition, Providence Art Club, May 1901. Providence Art Club. 1901. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Edward Mitchell Bannister (1828-1901) - Find A..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Appiah-Duffell, Salima (February 26, 2015). "African American Artists and the Hudson River School – Smithsonian Libraries / Unbound". Unbound. Smithsonian Libraries and Archives. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- "Boston Street Scene (Boston Common)". The Walters Art Museum. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Wagner, Anne Prentice. "Newspaper Boy" (PDF). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Sweren, Evan (27 February 2015). "For sale: the Bannister House". Brown Daily Herald. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- Robinson, Shantay (January 9, 2020). "Black Art: Ghettoizing Art or Creating Space?". Black Art in America. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Armstead, Myra B. Young (2005). "Revisiting Hotels and Other Lodgings: American Tourist Spaces through the Lens of Black Pleasure-Travelers, 1880-1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. 25: 136–159. ISSN 0888-7314. JSTOR 40007722. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Cook, Karen (1973). "The Museum of African Art". African Arts. 6 (3): 21–63. doi:10.2307/3334690. JSTOR 3334690.

- "Edward Mitchell Bannister". Rhode Island College. Retrieved 2014-03-16.

- "Search Statement : Kenkeleba Gallery (New York, N.Y.)". rihs.minisisinc.com. The Rhode Island Historical Society. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Edward Mitchell Bannister ~ June 9 - October 8, 2018". Gilbert Stuart Birthplace & Museum | North Kingstown, Rhode Island. 4 June 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Mitra, Mili (1 November 2017). "Mitra '18: In support of Bannister Street". Brown Daily Herald. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "Artist: Bannister, Edward Mitchell (1828-1901)". Catalogues Raisonnés in Preparation. or Art Research (IFAR)-Catalogues Raisonnés in Preparation. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- "'The Vault' on Benevolent St. remains closed, for now". The Brown Daily Herald. September 29, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-30.

- "The Reeves Collection Of Ceramics At Washington And Lee University by Ron Fuchs II". InCollect.

- Downing, Neil (March 1, 2009). "Black contributions kept alive". Providence Journal. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Coelho, Courtney (13 May 2015). "Brown to renovate historic Bannister House". News from Brown. Brown University. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

The house at 93 Benevolent Street, once home to African American artist Edward Mitchell Bannister and currently owned by Brown University, will be fully renovated, returned to its original wood exterior ...

- "Newspaper Boy by Edward Mitchell Bannister / American Art". si.edu. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- "Palmer River". The Athenaeum. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

Bibliography

- Bannister, Edward Mitchell. Edward M. Bannister: A Centennial Retrospective. Newport, R.I.: Roger King Gallery of Fine Art, 2001. OCLC 49568395 Edward M. Bannister: a centennial retrospective. (WorldCat.org)

- Bearden, Romare and Harry Henderson, A History of African American Artists from 1792 to the Present (Pantheon, 1993).

- Hartigan, Lynda Roscoe, Sharing Traditions: 5 Black Artists in 19th-Century America. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Pr., 1985, pp. 69–82.

- Perry, Regenia A., Free within ourselves: African American artists in the collection of the National Museum of American Art. Smithsonian Inst., 1992. pp. 23–27.

- Van Siclen, Bill, "The Varied Landscape of Edward Bannister's Career". The Providence Journal, L. Nov 01 2001. ProQuest. Web. 26 Oct. 2017.

External links

- Edward Mitchell Bannister at American Art Gallery

- Biographical sketch and images at World Wide Art Resources

- Narratives of Art and Identity: The David C. Driskell Collection

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Mitchell Bannister. |

_-_Walters_372766.jpg.webp)