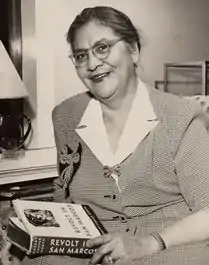

Elizabeth Bender Roe Cloud

Elizabeth Bender Roe Cloud (April 2, 1887 – September 16, 1965) was an Ojibwe activist and educator. A product of the Native American Boarding School System, she graduated with teaching credentials from the Hampton Institute and taught from 1908 though 1916. She then joined her husband and helped administer the American Indian Institute of Wichita, Kansas for twenty-five years. In the 1940s, she founded the Oregon Trails Women's Club with tribe members from the Umatilla Indian Reservation. She served as the National Chair of Indian Welfare for the General Federation of Women's Clubs for eight years, the first American Indian to hold the post. Roe Cloud received the National Mother of the Year award in 1950 and in 1952, she was honored as the "Outstanding Indian" of the year by the American Indian Exposition of Anadarko, Oklahoma. She is noted for having used her influence as an educated indigenous woman to advocate for Native American self-determination.

Elizabeth Bender Roe Cloud | |

|---|---|

Equay Zaince | |

| |

| Born | Elizabeth Georgiana Bender April 2, 1887 White Earth Indian Reservation, in northwestern Minnesota |

| Died | September 16, 1965 (aged 78) |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Elizabeth Roe-Cloud, Elizabeth Bender Cloud |

| Occupation | activist, educator, Native American club woman |

| Years active | 1908–1958 |

| Children | 6; including Woesha Cloud North |

| Relatives | Chief Bender (brother) Renya K. Ramirez (granddaughter) |

Early life

Elizabeth Georgiana Bender (native name: Equay Zaince)[Notes 1] was born on April 2, 1887[Notes 2] on the White Earth Indian Reservation in northwestern Minnesota to Pay show de o quay (Mary née Razor or Razier), of the Mississippi Chippewa band and Albertus Bliss Bender, a German immigrant.[4][7][8][6][3] Her father was a logger and after he and Mary married, he lived on her allotment, continued to log, and also hunted and fished.[5] Bender's mother was an herbalist and healer, who served as a midwife to her tribe. One of eleven children born to the couple, Elizabeth was the sixth child[3] and one of five who attended Hampton Institute.[5] Her older sister Anna was also an educator and two of her older brothers John and Charles Albert "Chief" Bender were noted baseball players. Chief was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1953.[9][10]

Bender attended boarding schools in Minnesota, beginning her studies at around age nine at the Catholic Sisters School in St. Joseph, Minnesota. After her first year, she transferred to the Catholic Sisters School closer to home, in White Earth, for another year. Between 1898 and 1902,[11] she took courses at the Pipestone Boarding School for half a day and then performed manual labor for the other half-day.[12] She went on to join her sister Anna and further her education at the normal school of the Hampton Institute in 1903.[13][14] Both she and her sister Anna participated in the work-away summer programs, where they were paid for performing domestic services. In 1904, they were placed in separate houses near Boston, which allowed them to spend time together, as well as making a trip to watch their brother Chief play baseball.[15] Completing her studies in 1907, she remained at Hampton taking post-graduate courses in teaching and domestic science.[14][16][15]

Career

In 1908, Bender was sent to the Blackfeet Reservation in Browning, Montana, where she would teach for two years. In 1910, she returned east and completed a nursing course in Philadelphia at Hahnemann Hospital. In 1912, she returned to the Blackfeet Reservation. The following year,[17] she moved on to the school at the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation in Montana, where she remained until 1914.[18][19] At both of the reservations, she not only taught, but served as housemother to the boarders, occasionally as their cook, and even treated the students for trachoma.[18] She returned to Hampton to complete a Home Economics course in 1914 and 1915.[16][19] During this same time frame, she attended the Fourth Annual Conference of the Society of American Indians held between October 6 and 11, 1914 in Madison, Wisconsin.[14] Bender had joined the organization when she graduated[16] and it was at this meeting that she would meet Henry Roe Cloud, a full-blood Winnebago tribe member.[14] The two immediately began a relationship, which continued even after Bender finished her studies at Hampton and went to teach at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1915.[20] Simultaneously, Roe Cloud went to Wichita, Kansas and founded the Roe Institute, later known as the American Indian Institute,[21][22] a college preparatory school for indigenous men.[16] While she was at Carlisle, Bender formed a Camp Fire Girls program, to help girls learn domestic and artistic skills.[23] On 12 June 1916, Bender married Roe Cloud at her brother Chief's home in Philadelphia.[24]

The couple made their home in Wichita, where Elizabeth worked at the American Indian Institute (AII), serving as matron and financial manager.[13] Because Henry had no prior experience teaching, she often served as an advisor and took an active part in running the school for twenty years.[25][16] Unlike other Native American schools, the curriculum of AII included courses on indigenous cultures, in addition to the academic lessons.[26] Over the next several years, their family grew to include Elizabeth Marion (born 1917), Anne Woesha (born 1918), Lillian Alberta (born 1920), Ramona Clark (born 1922) and Henry Jr. (1926–1929). When Henry Jr. died, they adopted Jay Hunter, a family friend, who was not orphaned, but joined their family as was customary among the Winnebago.[27] In 1931, Henry took a job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and began traveling as an investigator researching conditions, such as education, health and poverty, among Native American communities.[28] He was often absent from the school and Elizabeth supervised it during those absences.[29] In 1932, she returned to school, taking courses at Wichita University part time, where she eventually earned her bachelor's degree.[30] Henry had been appointed as the superintendent of the Haskell Institute in 1933 and would work in Lawrence for the next two years.[31] Elizabeth resigned from her duties at AII in 1934, but continued to live in Wichita so that the children could finish their schooling and herself took graduate courses at the University of Kansas.[30] In 1937, fire destroyed the school and after struggling to remain open for two years, the decision was made to close the school in 1939.[32] That same year, Elizabeth was asked by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to serve as a delegate to represent minorities for the White House Conference on Children and Youth, examining children and the role of democracy. At the conference, she met Sadie Orr Dunbar, who was the current president of the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC).[33]

In 1940, the family relocated to the Umatilla Indian Reservation, where Henry became superintendent of the agency there.[34][35] Elizabeth became involved in the Woman's club movement, founding the Oregon Trails Women's Club from women on the reservation.[36] Joining the Oregon State Federation of Women's Clubs, she was appointed to serve as chair for the state organization's Indian Welfare Committee[37] in 1948. Her duties were to implement the club's outreach to Native American women and to help the club members implement the goals of equal citizenship for indigenous people.[38] Henry died of heart failure in 1950, before Elizabeth won the Golden Rule Foundation's Mother of the Year award for 1950.[8] In part, the award was given because all four of her daughters had gone on to earn university educations. Marion had been the first American Indian to graduate from Wellesley College, Anne Woesha was the first indigenous woman to graduate from Vassar, Lillian completed her education at the University of Kansas and Ramona graduated from Vassar.[38] The award propelled her to national speaking and writing engagements and to head the national Indian Affairs Division for the GFWC.[39] She was the first Native American to be named mother of the year, as well as the first to head the GFWC's Indian Affairs Division,[40] which she led for eight years. Developing a "Point Four Program", which included desegregating Indian populations from mainstream schools and opportunities, providing leadership training, expanding cultural programs, and conducting studies.[41] She urged each affiliated club to develop Indian Affairs committees and by 1951 had offices in forty state affiliates. She also pressed for state organizations to offer educational scholarships for Native children.[42] In regard to the last item, Roe Cloud traveled over 22,000 miles over the next two years assessing conditions for tribes in twenty-two states and the Territory of Alaska.[41] Simultaneously, she began participating as a field officer of the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI). She had directed a two-week summer strategy workshop, held in Brigham City, Utah in 1951 and began working as a co-director, with D'Arcy McNickle for the American Indian Development Project.[43]

Roe Cloud used her voice as an advocate for indigenous people, arguing that though Native Americans could learn self-sufficiency, the government had to cease efforts to victimize tribes by usurping their power, their natural resources, and their customs. She proposed a Charter of Indian Rights, developed in the AID Project to the GFWC, which was adopted in 1952. In part, the plan called for the government to speed up its efforts to help tribes eliminate poverty and illiteracy, provide adequate health and resource safeguards, and allow Native communities the autonomy to manage their own affairs once they had shown an ability to do so.[44] She saw the role of the AID Project as one of advising and assisting in developing strategy, but allowing communities to establish their own goals and management processes.[45] That same year, she was selected as the "Outstanding Indian" of the year by the American Indian Exposition of Anadarko, Oklahoma.[46] When Helen Peterson became the executive director of NCAI in 1953, Roe Cloud helped her transition into the job and took her to reservations throughout Indian country to make assessments of the various tribes and establish networking contacts.[47] With the passage of House concurrent resolution 108, designed to implement the Indian termination policy to discharge federal trustee responsibility for Indian lands and force the tribes into assimilating to mainstream culture, Roe Cloud pressed the GFWC to oppose legislation aimed at terminating tribes.[48] The GFWC leadership joined the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Legion, other organizations, and the Native American community in opposition to termination, ultimately defeating the policy in the 1960s.[49]

Death and Legacy

Roe Cloud died on September 16, 1965 in Portland, Oregon.[50] Her ability to straddle two worlds, during the contentious decades of the Indian termination policies, allowed her to serve as a role model for generations which followed her activism. Rather than adopt the position of GFWG's first Indian Welfare Committee Chair, Stella Atwood, who backed American Indian rights, but proclaimed, "I will work for the Indians but not with them," Roe Cloud tried to involve indigenous people in creating their own solutions and reforms.[42][51] Her daughter, Anne Woesha, would become an activist after her mother's death, participating in the Occupation of Alcatraz.[52]

Notes

- Elizabeth Roe Cloud's allotment number was 556, as shown on the 1930 Chippewa Census.[1] This allotment number is identical with that assigned to Equay Zaince on the Minnesota Historical Society Records.[2]

- Tetzloff gives Bender's birth date April 2, 1887.[3] This conflicts with the date of July 1888 shown on the 1900 census;[4] but all of the dates on the 1900 census for the Bender siblings do not conform to other published dates. For example, Anna's birth date in Molin is given as February 22, 1885[5] and Chief's birth date in Kashatus is given as May 5, 1884.[6]

References

Citations

- Chippewa Census 1930, p. 562.

- Minnesota Historical Society 2011, p. 12.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 80.

- U. S. Census 1900, p. 5B.

- Molin 1988, p. 94.

- Kashatus 2006, p. 5.

- Chippewa Census 1896, p. 197.

- Indianapolis Recorder 1950, p. 9.

- Swift 2008, p. 165.

- Kashatus 2006, p. 150.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 81.

- Molin 1988, p. 95.

- Gridley 1936, p. 34.

- Messer 2009, p. 93.

- Molin 1988, p. 97.

- Nesper 2014.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 84–85.

- Messer 2009, p. 94.

- The Red Lake News 1915, p. 2.

- Messer 2009, p. 95.

- The Wichita Beacon 1921, p. 12.

- Tihen 2002, pp. 2–3.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 85–86.

- The Native American 1916, p. 240.

- Messer 2009, pp. 94, 102.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 90.

- Messer 2009, p. 108.

- Messer 2009, p. 107.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 91.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 92–93.

- Goodwin 2017, p. 69.

- Tihen 2002, p. 3.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 94–95.

- Goodwin 2017, p. 71.

- U. S. Census 1940, p. 2B.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 95.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 78.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 97.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 99.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 97, 99.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 100.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 104.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 101.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 102.

- Goodwin 2017, p. 97.

- The Ada Weekly News 1952, p. 6.

- Cowger 1999, p. 110.

- Tetzloff 2009, pp. 102–103.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 103.

- Statesman Journal 1965, p. 5.

- Goodwin 2017, p. 120.

- Tetzloff 2009, p. 105.

Bibliography

- Cowger, Thomas W. (1999). The National Congress of American Indians : the founding years. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-1502-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodwin, John A. (April 2017). "Without Destroying Ourselves": American Indian Intellectual Activism for Higher Education, 1915–1978 (PDF) (PhD). Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gridley, Marion Eleanor (1936). Indians of Today. Crawfordsville, Indiana: Lakeside Press, R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company. OCLC 2958703.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kashatus, William C. (2006). Money Pitcher: Chief Bender and the Tragedy of Indian Assimilation. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-02862-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Messer, David W. (2009). Henry Roe Cloud: A Biography. Lanham, Maryland: Hamilton Books. ISBN 978-0-7618-4919-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Molin, Paulette Fairbanks (Fall 1988). ""Training the hand, the head, and the heart": Indian Education at Hampton Institute" (PDF). Minnesota History. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society. 51 (3): 82–98. ISSN 0190-6348. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nesper, Larry (2014). "The Society of American Indians Fourth Annual Meeting". Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Swift, Tom (2008). Chief Bender's Burden: The Silent Struggle of a Baseball Star. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8032-4322-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tetzloff, Lisa (2009). "Elizabeth Bender Cloud: "Working For and With Our Indian People"". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University via University of Nebraska Press. 30 (3): 77–115. ISSN 0160-9009. Retrieved 10 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete (subscription required)

- Tihen, Edward N., ed. (2002). "Tihen Notes: Henry Roe Cloud, American Indian Institute, Roe Indian Institute" (PDF). Wichita State University Libraries’ Department of Special Collections. Wichita, Kansas: Wichita State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "1896 Census: White Earth Mississippi Chippewa". Archive.org. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 26 August 1896. p. 197. NARA microfilm series T595 roll 652. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "1900 U.S. Census: White Earth Indian Reservation, Polk County (Becker), Minnesota". FamilySearch. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 6 June 1900. p. 5B. NARA microfilm series T623 roll 798. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "1930 Census: White Earth Consolidated Chippewa". Archive.org. Washington, D. C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 1 April 1930. p. 562. NARA microfilm series T595 roll 65. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "1940 U.S. Census: Umatilla Indian Reservation, Precinct #16, Umatilla County, Oregon". FamilySearch. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. 9 April 1940. p. 2B. NARA microfilm series T627 roll 3380. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- "Indian Citizenship Day at Hampton Institute". Ada, Oklahoma: The Ada Weekly News. 21 August 1952. p. 6. Retrieved 10 August 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bender-Cloud". The Native American. Phoenix, Arizona: Phoenix Indian School. 17 (13): 240. July 1, 1916. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "Hampton Grad, 'Mother of 1950' Visits Campus". Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana: Indianapolis Recorder. 10 June 1950. p. 9. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "Indian Citizenship Day at Hampton Institute". Red Lake, Minnesota: The Red Lake News. 1 March 1915. p. 2. Retrieved 9 August 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Noted Educator Born in Wigwam". Wichita, Kansas: The Wichita Beacon. 2 January 1921. p. 12. Retrieved 9 August 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Roe Cloud Rites Set for Monday". Statesman Journal. Salem, Oregon. 20 September 1965. p. 5. Retrieved 10 August 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "U.S. General Land Office. Crookston Land District—Register of Indian Allotment Entries Under the Nelson Act: White Earth Reservation" (PDF). MNHS Library. St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society. 2011. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2017.