Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis

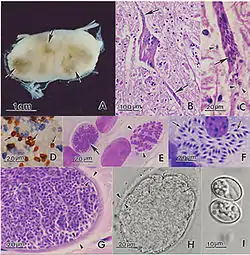

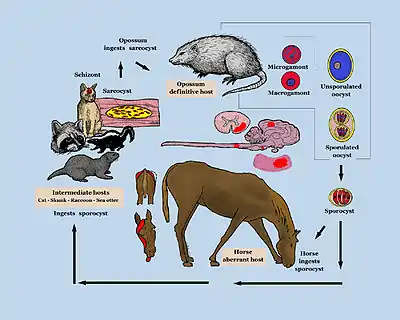

Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis (EPM), is a disease caused by the apicomplexan parasite Sarcocystis neurona[1] that affects the central nervous system of horses.

History

EPM was first discovered in the 1960s by the American biologist Dr. Jim Rooney.[2] The disease is considered rare, though recently, an increasing number of cases have been reported. Previous research identified the "barn cat" as the definitive host of the disease. However, since that time it has been learned that the definitive host is the opossum, while any of a number of mammals can serve as intermediate hosts in the disease's two-host life-cycle. Those with horses should not panic and kill opossums or wildlife rather keep feed covered and stalls clean.[3]

The term EPM refers to the clinical neurologic symptoms caused by the parasite, not infection itself. The majority of horses infected with S. neurona do not exhibit neurologic symptoms consistent with EPM. There are six subspecies of S. neurona which can be identified by surface antigens (SAG). Equine EPM is caused by the parasites that exhibit SAG1, SAG5, and SAG6. SAG1 and SAG5 are responsible for the majority of EPM cases in horses.[4] Horses produce antibodies to these surface antigens. Serum antibody testing is available that measures levels of these antibodies in the blood of horses, which is helpful in diagnosing EPM in an ataxic horse. Serial blood levels are helpful in guiding treatment. In experimentally infected horses it takes 14 days from infection to positive antibody tests.[5] 80% of horses with EPM have positive antibody tests. A negative antibody test in the presence of EPM results if testing is done before 17 days or if the horse has been treated with antiprotozoal drugs which delays antibody production.

Causes

EPM is caused by the parasite Sarcocystis neurona. The life cycle of S. neurona is well described. In order to complete its life cycle this parasite needs two hosts, a definitive and an intermediate. In the laboratory, raccoons, cats, armadillos, skunks, and sea otters have been shown to be intermediate hosts. The opossum is the definitive host of the disease, passing the parasite through feces. Horses contract EPM from contaminated feed or water. Horses cannot pass the disease among themselves; that is, one horse cannot contract the disease from another infected horse. The horse is a dead-end, or aberrant, host of the parasite.[6]

Symptoms

The most common symptoms of EPM are ataxia, general weakness with muscle spasticity. However this is not specific to EPM and is common to many other neurological disorders. Clinical signs among horses with EPM include a wide array of symptoms that may result from primary or secondary problems. Some of the signs are difficult to distinguish from other problems, such as lameness, which can be attributed to many different causes. Apparent lameness, particularly atypical lameness or slight gait asymmetry of the rear limbs are commonly caused by EPM. Focal muscle atrophy, or even generalized muscle atrophy or loss of condition may result. Secondary signs also occur with neurologic disease. Airway abnormalities, such as laryngeal hemiplegia, snoring, or airway noise of undetermined origin may result from damage to the nerves which control the throat, although this is quite uncommon.

In experimentally infected horses, very early signs included loss of appetite, decreased tongue tone, facial paresis, altered mental status, generalized weakness, and lameness.

It is thought that Sarcocystis neurona does not need to enter the CNS to cause disease, in some cases S. neurona has been found in the CNS but usually not. In cases where S. neurona is found in the CNS, white blood cells probably play a role in the parasite's penetration of the blood brain barrier.

Treatment and prevention

EPM is treatable, but irreversible damage to the nervous system is possible. It is important to identify the disease as early as possible and begin treatment with antiprotozoal drugs. There are currently three FDA approved treatments available in the US: ReBalance (sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine),[7][8] Marquis (ponazuril),[9] and Protazil (diclazuril). These drugs minimize the infection but do not kill the parasite. The use of anti-inflammatory agents such as Banamine, corticosteroids, or phenylbutazone are often used to help reduce inflammation and limit further damage to the CNS. Antioxidants, such as vitamin E may help promote the restoration of nervous tissue. Response to treatment is often variable, and treatment may be expensive. Recently, antiprotozoal treatments that kill the parasite and clear the infection have shown promise.[10] The inflammatory component is thought responsible for the symptoms of EPM; anti inflammatory drugs that target the IL-6 pathway have been particularly effective at reversing symptoms.

Control of this disease includes proper storage of hay and feed, the control of "barn cats" on the property, and prompt disposal of animal carcasses. No vaccine is available.

References

- Dubey, J. P.; Davis, S. W.; Speer, C. A.; Bowman, D. D.; de Lahunta, A.; Granstrom, D. E.; Topper, M. J.; Hamir, A. N.; Cummings, J. F.; Suter, M. M. (April 1991). "Sarcocystis neurona n. sp. (Protozoa: Apicomplexa), the Etiologic Agent of Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis" (Submitted manuscript). The Journal of Parasitology. 77 (2): 212–8. doi:10.2307/3283084. JSTOR 3283084. PMID 1901359.

- Rooney, J. R.; Prickett, M. E.; Delaney, F. M.; Crowe, M. W. (1970-07-01). "Focal myelitis-encephalitis in horses". The Cornell Veterinarian. 60 (3): 494–501. ISSN 0010-8901. PMID 5464755.

- Reed, S.M.; Furr, M.; Howe, D.K.; Johnson, A.L.; MacKay, R.J.; Morrow, J.K.; Pusterla, N.; Witonsky, S. (March 2016). "Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis: An Updated Consensus Statement with a Focus on Parasite Biology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention". Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 30 (2): 491–502. doi:10.1111/jvim.13834. PMC 4913613. PMID 26857902.

- Crowdus, Carolyn A.; Marsh, Antoinette E.; Saville, William J.; Lindsay, David S.; Dubey, J.P.; Granstrom, David E.; Howe, Daniel K. (November 2008). "SnSAG5 is an alternative surface antigen of Sarcocystis neurona strains that is mutually exclusive to SnSAG1". Veterinary Parasitology. 158 (1–2): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.08.012. PMID 18829171.

- Sofaly, C. D.; Reed, S. M.; Gordon, J. C.; Dubey, J. P.; Oglesbee, M. J.; Njoku, C. J.; Grover, D. L.; Saville, W. J. A. (December 2002). "Experimental Induction of Equine Protozoan Myeloencephalitis (EPM) in the Horse: Effect of Sarcocystis neurona Sporocyst Inoculation Dose on the Development of Clinical Neurologic Disease". The Journal of Parasitology. 88 (6): 1164–70. doi:10.2307/3285489. JSTOR 3285489. PMID 12537112.

- "Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis: Introduction". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- "ReBalance® sulfadiazine/pyrimethamine oral suspension for horses". Prnpharmacal.com. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- "Freedom of information summary: NADA 141-240, REBALANCE Antiprotozoal Oral Suspension" (PDF). FDA. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Furr, M.; McKenzie, H.; Saville, W. J A.; Dubey, J. P.; Reed, S. M.; Davis, W. (June 2006). "Prophylactic administration of ponazuril reduces clinical signs and delays seroconversion in horses challenged with Sarcocystis neurona". Journal of Parasitology. 92 (3): 637–643. doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2006)92[637:PAOPRC]2.0.CO;2.

- Ellison, Siobhan P.; Lindsay, David S. (2012). "Decoquinate combined with levamisole reduce the clinical signs and serum SAG 1, 5, 6 antibodies in horses with suspected equine protozoal myeloencephalitis" (PDF). The International Journal of Applied Research in Veterinary Medicine. 10 (1): 1–7.

Bibliography

Cutler T, MacKay RJ, Ginn PE, et al. Are Sarcocystis neurona and Sarcocystis falcatula synonymous? A horse infection challenge. J. Parasitol. 85:301-305, 1999.

Fenger CK, Granstrom DE, Gajadhar A, et al. Experimental induction of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in horses using Sarcocystis sp. sporocysts from the opossum (Didelphis virginiana). Vet Parasitol 68:199-213, 1997.

MacKay RJ. Serum antibodies to Sarcocystis neurona-half the horses in the United States have them! JAVMA 210:482-483, 1997.

Granstrom DE. Diagnosis of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis: Western blot analysis. Proc Am Coll Vet Intern Med Forum 587–590, 1993.

Granstrom DE, MacPherson JM, Gajadhar AA, et al. Differentiation of Sarcocystis neurona from eight related coccidia by random amplified polymorphic NA assay. J Molec Cellular Probes 8:353-356, 1994.

Hamir AN, Moser G, Galligan DT, et al. Immunohistochemical study to demonstrate Sarcocystis neurona in equine protozoal myeloencephalitis. J Vet Diagn Invest 5:418-422, 1993.

Furr M, MacKay R, Granstrom D, et al. J Vet Intern Med 16: 618–621, 2002.

Ellison SP, Omara-Opyeme AL, Yowell C, Dame J. Molecular characterization of a major 29 kDa surface antigen of Sarcocystis neurona. J Parasit 32:217-225, 2002.

Andrews FM. A review: Determining the sensitivity and specificity of western blot tests for diagnosis of Equine protozoal myeloencephalitis. Equine Med Rev 2003.11.

Ellison SP. Development of a recombinant protein for the identification of S. neurona infections in horses. [PhD dissertation]. University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, 2001.

Amery, W K P and Bruynseels, J M. Levamisole, the story and the lessons. 1992, Inr. J Immunopharmac, 14(3):481 doi: 481–86 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90179-O

Sajid, M S. Immunomodulation effects of various anti-parasitics:a review. 2006, Parasitol, Vol. 132, pp. 301–13

Lindsay, David A. David Lindsay Decoquinate,4-hydroxyquinalones and hydroxyquinalones and napthoquinones for the prevention and treatment of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis caused by Sarcocystis neurona. 2001.

Ellison, Siobhan P. sarcocystis. Pathogenes Inc.[Online] Pathogenes Inc, 2003

Limited genetic diversity among Sarcocystis neurona strains infecting southern sea otters precludes distinction between marine and terrestrial isolates. Wendte JM, Miller MA, Nandra AK, Peat SM, Crosbie PR, Conrad PA, Grigg ME. 1–2, Apr 2010, Vet Parasitol, Vol. 169, pp. 37–44

Development of an ELISA to detect antibodies torSAG 1 in the horse. S P Ellison, T Kennedy, KK Brown. 4, 2003, J App Res Vet Med, Vol. 1, pp. 318–327

Experimental infection of horses with S. neurona merozoites as a model for Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis. Ellison, S. P., Greiner, E., Brown, K K., Kennedy, T. 2, 2004, J App Res Vet Med, Vol.2, pp. 79–89.

Characterization of a Sarcocystis neurona isolate from a Missouri horse with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis. Marsh AE, Johnson PJ, Ramos-Vara J, Johnson GC. 2–4, Feb 2001, Vet Parasitol, Vol. 95, pp. 143–54.

Cytokine Gene Expression in Response to SnSAG1in Horses with Equine Protozoal Myeloencephalitis. Spencer JA, Deinnocentes P, Moyana EM, Guarino AJ, Ellison SP, Bird RC, and BlagburnBL. 2004, J. Parasitol.

Immune response to Sarcocystis neurona infectionin naturally infected horses with equine protozoal myeloencephalitis. Yang J., Ellison S., GogalR., Norton H., Lindsay D S., Andrews R., WardR., Ward D., Witonsky. 3–4, 2006, Vol. 138, pp. 200–10.

In vitro suppressed immune response in horses experimentally infected with Sarcocystis neurona. Witonsky S., Ellison S., Yang J., Gogal R., NortonH., Yasuhiro S., Sriranganathan N., Andrews F., Ward D., Lindsay DS. 1, 2008, Vol. 12, p. 1.

Antibody index and specific antibody quotient inhorses after intragastric administration of Sarcocystis neurona sporocysts. Heskett KA, Mackay RJ. 3, Mar 2008, Am J Vet, Vol. 69, pp. 403–9.

An equine protozoal myeloencephalitis challenge model testing a second transport after inoculation with Sarcocystis neurona sporocysts. Saville WJ, Sofaly CD, Reed SM, Dubey JP, Oglesbee MJ, Lacombe VA, Keene RO, Gugisberg KM, Swensen SW, Shipley RD, Chiang YW, Chu HJ, Ng T. 6,2006, J Parasitol, Vol. 90, pp. 1406–10.