Eremiascincus richardsonii

The broad-banded sand-swimmer or Richardson’s skink (Eremiascincus richardsonii) is a species of skink found in Australia.[2]

| Eremiascincus richardsonii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Eremiascincus |

| Species: | E. richardsonii |

| Binomial name | |

| Eremiascincus richardsonii (Gray, 1845) | |

Naming

The Eremiascincus genus was created under the Sphenomorphus Group due to having such distinct differences and morphological adaptions over other skinks in the genus, even though they look similar.[3] These skinks possess traits that are unique to those other skinks in this category.[3] The Broad Banded Sand Swimmer was derived and named after John Richardson, who was a Scottish Naturalist.[4]

Physical description

This skink has a snout to vent length of around 113mm as a maximum, however has an average SVL of 75mm.[5] This skink is a medium sized skink[6] and the name corresponds well with the species for its ability to practically ‘swim’ over the sand to chase and catch its prey.[7] The tail length varies but is up to 171% longer than the SVL.[4] They are a very distinct skink in their looks, although are similar in many ways to the E. fasciolatus. The Broad Banded Sand-Swimmer can be identified based upon the pattern of the caudal bands that it possesses and the number of caudal bands it possesses to distinguish between other sand-swimmers[3] which can be seen in image 3. These skinks have between 19-32 bands on the tail, however the Narrow Banded possesses more (between 35-40).[5] On the nape, the broad banded possesses 8-14 bands that whereas the narrow-banded swimmer 10-19 narrow bands on its nape.[8] The bands on the body are much broader than those of the narrow banded, and they are generally less regular than the narrow banded. If the skink has lost its tail in the past, using the bands to distinguish the skink is unable to be used, as once the tail is regrown, it does not possess the caudal bands.[9] This skink possesses a snout that is less depressed that that of the E. fasciolatus. The colour of these skinks can be a pale brown to dark reddish colour,[5] with the young hatchlings having a bright yellow colour[10] and some of these variances can be seen in images 1 and 2. The scales of this skink are very shiny and has five toes on each of the animal’s feet- both the forelimbs and hindlimbs.[5] Another way that the E.richardsonii can be identified, is through the parietal scales being in contact rather than being separated.[11] This is also a way to tell if the skink has a transparent lower eyelid as skinks with round eyes do not have this feature, however when they are hold an elliptical eye shape.[11]

Diet

This sand swimmer has a diet that can consists of a variety of different animals that live around them and can include such insects as grasshoppers, moths, beetles, termites, spiders and has been described on occasion to eat other small lizards.[12] This skinks also can eat fruit as part of its diet.[5] When the E.richardsonii is agitated by waiting to capture its prey, the tail waves in a “cat like fashion” and the E.Richardsonii forages over large distances and is an aggressive hunter.[13]

Distribution

The E.richardsonii is commonly spread throughout arid regions of Australia and has been identified in a range of States around Australia that have desert skinks. This includes areas of Western Australia such as the Nullarbor Plain and the Tanami.[4] In New South Wales some of these locations include the North Far Western Plains right through to the Southern Far Western Plains and many arid areas in between, with some isolated occurrences in the Northern North Western Slopes of the state[5].In the Northern Territory, distribution includes the Kimberly Desert and the Macdonnell Ranges, and within South Australia, this species can be found in the Simpson Desert and other arid regions[14].These skinks are not known to be located or to inhabit arid areas of Victoria.[8] Although both species of the banded skinks inhabit sandy soils, the E.richardsonii can also be found on heavy and stony soils, not just limited to desert sands.[8] This reptile has also been found in deep crevices and caves due to the nocturnal life that it lives and also other dark areas such as rabbit holes.[3]

Reproduction

This species in the past was believed to carry its young which is known to be viviparous, however this was later found to be incorrect. Newer studies that have been conducted on this have proven that the E.richarsonii is actually oviparous which means it lays eggs. The skink commonly lays 4-5 eggs per clutch, however this did grow slightly with one of the studies finding that there was an increase in clutch size when the skink was larger.[9] This same study also explained that sexual maturity for the E.richardsonii was 69mm for females and 67mm for males.

Adaptions

Sand swimmers have colours that have adapted to be almost the same colour of the sand that surrounds them and have been described to look the same as the sand when either looking from above the skink or from the side.[15] They have also gained a transparent disk on their eyes that allows them to burrow into the sand without getting sand in them, which is known as a transparent lower lid as described previously.[11] This allows the skink to not get sand in its eye but still giving it the ability to see through this cover. The interesting part of the adaptions of this reptile, is that although they are a species that has adapted to desert environments, this species is actually less tolerant of heat and is more susceptible to dehydration along with heat stress than other reptiles that live within deserts around the world.[10]

E. richardsonii is a part of the Eremiascincus family, which has 15 different species. The Eremiascincus family are skinks that are nocturnal, fossorial and territorial skinks and the reason behind the name of this family of 'sand swimmers' is that they have the interesting ability to evade predators and quickly burrow into the sand when they need to.[14]

This species is a thigmotherm, meaning that it primarily rely on heat exchange as the substrate for body temperature and they come out after dark where they reply on air temperature and patches of warm ground for this.[16]

References

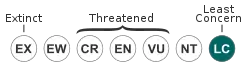

- Cowan, M.; Ford, S.; How, R. (2017). "Eremiascincus richardsonii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T109471556A109471574. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T109471556A109471574.en. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Eremiascincus richardsonii at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 22 March 2015.

- Greer, Allen E. (1979-09-30). "Eremiascincus, a new generic name for some Australian sand swimming skinks (Lacertilla: Scincidae)". Records of the Australian Museum. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.32.1979.458. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Storr, G. M.; Smith, Lawrence Alec; Johnstone, R. E. (1999). Lizards of Western Australia. I, Skinks (Rev. ed.). Perth: Western Australian Museum. ISBN 0-7307-2656-8. OCLC 42335524.

- Swan, Gerry (1990). A field guide to the snakes and lizards of New South Wales. Winmalee, NSW: Three Sisters Productions. ISBN 0-9590203-9-X. OCLC 23830309.

- Mecke, Sven; Doughty, Paul; Donnellan, Stephen C. (2013-08-22). "Redescription of Eremiascincus fasciolatus (Günther, 1867) (Reptilia: Squamata: Scincidae) with clarification of its synonyms and the description of a new species". Zootaxa. 3701 (5): 473–517. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3701.5.1. ISSN 1175-5334.

- Vandenbeld, John (1988). Nature of Australia : a portrait of the island continent. Sydney, NSW: Collins Australia. ISBN 0-7322-0003-2. OCLC 19823940.

- Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry. A complete guide to reptiles of Australia (Fifth ed.). Chatswood, NSW. ISBN 978-1-925546-02-6. OCLC 1003055388.

- James, Cd; Losos, Jb (1991). "Diet and reproductive biology of the Australian sand-swimming lizards, Eremiascincus (Scincidae)". Wildlife Research. 18 (6): 641. doi:10.1071/WR9910641. ISSN 1035-3712.

- Encyclopedia of Australian wildlife. Sydney: Reader's Digest. 1997. ISBN 0-86449-118-2. OCLC 40871074.

- "South Australian reptile keys". www.samuseum.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- "Scale tales: guide to Aussie skinks". Australian Geographic. 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2020-10-23.

- Cronin, Leonard. (2001). Australian reptiles and amphibians. Annandale, N.S.W.: Envirobook. ISBN 0-85881-186-3. OCLC 63041965.

- Horner, Paul (1992). Skinks of the Northern Territory. Darwin, NT, Australia: Northern Territory Museum of Arts and Sciences. ISBN 0-7245-2681-1. OCLC 76177157.

- Butler, Harry (1977). In the wild with Harry Butler. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Commission in association with Hodder and Stoughton (Australia). ISBN 0-642-97442-X. OCLC 29255858.

- Heatwole, Harold; Taylor, Janet A. (1987). Ecology of reptiles. Chipping Norton, NSW: Surrey Beatty & Sons. ISBN 0-949324-14-0. OCLC 20323013.